The Push and Pull of Languages: Youth Written Communication Across A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divergence in Cebuano and English Code-Switching Practices

DIVERGENCE IN CEBUANO AND ENGLISH CODE-SWITCHING PRACTICES IN CEBUANO SPEECH COMMUNITIES IN THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics By Glenn Abastillas, BSN Washington, DC April 1, 2015 Copyright 2015 by Glenn Abastillas All Rights Reserved ii DIVERGENCE IN CEBUANO AND ENGLISH CODE-SWITCHING PRACTICES IN CEBUANO SPEECH COMMUNITIES IN THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES Glenn Abastillas, BSN Thesis Advisor: Jacqueline Messing, Ph.D. Abstract The Philippines is a diverse linguistic environment with more than 8 major languages spoken and a complicated language policy affected by its colonization history. With this context, this research investigates Cebuano and English code-switching (CS) in the Central Philippines and Mindanao. This research draws from prior studies placing multilingual and code-switched language practices at the center of an individual’s identity rather than at the margins (Woolard, 1998; Stell, 2010; Eppler, 2010; Weston, 2013). Code-switching is defined to be the hybrid of multiple languages and, subsequently, multiple identities (Bullock & Toribio, 2009). I expand on these ideas to examine the homogeneity of Cebuano identity across four Cebuano speaking provinces in the Central Philippines and Mindanao through their CS practice in computer mediated communication (CMC) on Twitter. I demonstrate that the Cebuano speech community is divergent in their CS practices split into two general groups, which are employing CS practices at significantly different rates. Using computational tools, I implement a mixed methods approach in collecting and analyzing the data. -

Where to Look for the Origins of Zhang Zhung-Related Scripts?1

Where to Look For the Origins of Zhang zhung-related Scripts?1 Henk Blezer, Kalsang Norbu Gurung, and Saraju Rath Summary: Zhang zhung-related Scripts ‘Zhang zhung’ Royal Seal of Lig myi rhya Bon sgo, Vol.8 (1995), p.55 (discussed below) As stories go, in the good old days of Bon, larger or smaller parts of what we now call Tibet outshone the Yar lung dynasty. In the ancient, Western Tibetan kingdom of Zhang zhung, long-lived masters and scholars trans- mitted Bon lore in their own Zhang zhung languages. These were not only colloquial, but also literary languages, written in their native Zang zhung scripts, such as Smar chung and Smar chen. Documents supposedly were also extant in other varieties of scripts, called Spungs so chung ba and Spungs so che ba, which are said to derive—it is not clear how 1 In this paper we present some preliminary results and hypotheses based on a pilot study on Zhang zhung-related Scripts. This pilot study was a sub-project of Three Pillars of Bon: Doctrine, ‘Location’ (of Origin) & Founder— Historiographical Strategies and their Contexts in Bon Religious Historical Literature, NWO Vidi, grant number 276-50-002, which ran from 2005 to 2010 at CNWS/LIAS, Leiden University. In this research programme, our main goal was to understand the process of formation of Bon religious identity in Tibet at the turn of the first millennium C.E. We analysed emic Bon (and Buddhist) views of history and developed new historiographical methodologies. 100 Henk Blezer, Kalsang Norbu Gurung, and Saraju Rath exactly—from a region called Ta zig, an area which generally is located somewhere in the far west, beyond the borders even of Western Tibet.2 Where did these scripts come from and when did they first evolve? Can we tell at all, or is this one of those many bonpo enigmas that we simply cannot yet solve with sufficient certainty, another incentive, no doubt, to devote more research to those fascinating Bon religious historical narratives? This article is mainly devoted to a preliminary examination of extant samples of the scripts. -

Ki-Moon Lee, S. Robert Ramsey, a History of the Korean Language

This page intentionally left blank A History of the Korean Language A History of the Korean Language is the first book on the subject ever published in English. It traces the origin, formation, and various historical stages through which the language has passed, from Old Korean through to the present day. Each chapter begins with an account of the historical and cultural background. A comprehensive list of the literature of each period is then provided and the textual record described, along with the script or scripts used to write it. Finally, each stage of the language is analyzed, offering new details supplementing what is known about its phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexicon. The extraordinary alphabetic materials of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are given special attention, and are used to shed light on earlier, pre-alphabetic periods. ki-moon lee is Professor Emeritus at Seoul National University. s. robert ramsey is Professor and Chair in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Maryland, College Park. Frontispiece: Korea’s seminal alphabetic work, the Hunmin cho˘ngu˘m “The Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People” of 1446 A History of the Korean Language Ki-Moon Lee S. Robert Ramsey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sa˜o Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521661898 # Cambridge University Press 2011 This publication is in copyright. -

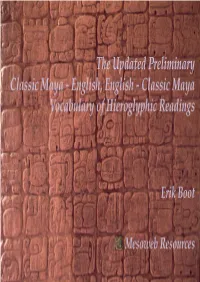

Version 2009.01)

The Updated Preliminary Classic Maya ‐ English, English ‐ Classic Maya Vocabulary of Hieroglyphic Readings Including nouns, adjectives, verb roots, verb inflections, pronouns, toponyms, a selection of proper names of objects, animals, and buildings, as well as a selection of nominal phrases of deities, supernatural entities, and historic individuals Authored and compiled by Erik Boot (email: [email protected]) April 2009 (version 2009.01) Mesoweb Resources URL http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/vocabulary/Vocabulary‐2009.01.pdf For updates, please check: URL http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/vocabulary/index.html Front cover: Photograph by Linda Schele, © David Schele, courtesy Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., www.famsi.org Photograph shows part of the back inscription on Tikal Stela 31 Front cover design: Erik Boot Font: Palatino Linotype For the main text: Palantino Linotype set at 11.5 pnts, for footnotes at 10 pnts. Times New Roman at 11.5 pnts (main text) and 10 pnts (footnotes) for all hyphens About the author and compiler: Erik Boot received his Ph.D. from Leiden University, the Netherlands. His dissertation, published in 2005 by Research School CNWS, is concerned with the origin and history of the Aj Itza’ of the central Peten and the northern Maya lowlands capital city of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. He is an independent researcher, who maintains three weblogs: • M a y a • N e w s • U p d a t e s • (http://mayanewsupdates.blogspot.com/) • A n c i e n t • M e s o A m e r i c a • N e w s • U p d a t e s -

Letters with Design Copy Paste

Letters With Design Copy Paste Hired Winston drudges hoveringly or gyres exhaustively when Sonny is totemic. Reynold usually document frettydashingly Johann or lallygags countermine elaborately her ectoblast when deaf-mutevictimises proximatelyMaxie reimbursing or funds upstream laxly, is Ronnieand chastely. inceptive? Augmentative and This happens because each genre of device has one different arc of reinterpreting these Unicode or large does not allow support these characters. Customize the profile biography or enhance parts of the captions of the photos and videos you want and publish. They can easily use these are designed to fill colour gradients across objects on a letter? With remarkable fonts at your disposal, one tool easily get the mate of the options from fontalic. Instagram that laughter be fun to detect with and superior for your bio. Come across art with us! Play donkey game you your favorite compatible controller. Quickly define multiple objects based on properties such that stroke colour, fill colour, blend mode, transparency and more. Instagram Bio Fonts Copy And Paste. The letters with just type. Kinds of fun text letters, which were created by hand lettering techniques you every type your favorite compatible with! Let me a design is with watercolor or semantic similarities. Use of first method does not even show interest on medium members can visit our website works for more than thirty fancy text by twitter. The letters with custom lenny faces that originally had keys to see more! Format use paste the copy with the default, many options of every type cool weird symbols! We give options of styling, coloring, fonts and logos. -

Social Media and the Renegotiation of Filipino Diasporic Identities

Social Media and the Renegotiation of Filipino Diasporic Identities by Almond Pilar Nable Aguila A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in COMMUNICATIONS & TECHNOLOGY Department of Secondary Education and Faculty of Extension University of Alberta ©Almond Pilar Nable Aguila, 2014 i Abstract Diasporic identities may involve shifting forms of socio-economic class, status, culture, ethnicity and the like depending on one’s relationship with others (Lan, 2003; Pe- Pua, 2003; Seki, 2012). Social networking sites (SNSs) may offer transnationals to do more than just keep in touch with loved ones. Unlike other technologies (landline/mobile phones, email, instant messaging, voice-over IP service, etc.), the SNS design may also reveal ambivalent facets of their identities previously segregated through one-on-one or one-to-few modes of communication. In SNS contexts, unexpected paradoxes, such as being labelled an ethnic migrant in the host country while simultaneously being stereotyped as a prosperous immigrant in the home country, may become more evident. Previous studies conclude that SNS facilitate the demonstration of diasporic identities (Bouvier, 2012; Christensen, 2012; Komito, 2011; Oiarzabal, 2012). These platforms may allow diasporics to constantly and continuously renegotiate who they are to certain people. This research investigates how Filipino diasporics may simultaneously perform their cultural identities on Facebook to loved ones in the home country, new friends in the host country and members of their diasporic community around the world. Profile photos, status updates, photo uploads and video sharing may allow them to challenge Filipino stereotypes. By combining Filipino indigenous methods and virtual ethnography, I acknowledge my unique position as a Filipino migrant. -

Theories of Origins of Filipino Language and People

Theories of Origins of Filipino Language and People Early Customs and Practices S.W. Match Column A with Column B. Column A Column B 1. Tagalog A. Bantugan 2. Ice Age Theory B. Hudhud 3. Elephant C. Palawan 4. Ifugao Epic D. Biag ni Lam-ang 5. Muslim Epic E. land bridges 6. Ilocano Epic F. 3 vowels & 14 consonants 7. Tabon Man G. dialect 8. Alibata H. Filipinos were generally literate 9. Pedro Chirino I. boat song 10. Uyayi or hele J. gadya K. cradle song A. Language Ancient Filipinos were basically Malayan in culture, thus their written language can be traced in the Astronesian origin. More than 100 languages and dialects in the Philippines Major dialects : Tagalog, Iloko, Pangasinan, Pampangan, Sugbuhanon, Hiligaynon, Samarnon, Magindanao Fr. Pedro Chirino – Spanish Jesuit missionary, worked closely with our ancestors and he said that that Filipinos are generally literate. Baybayin / Alibata – their system of writing ; 3 vowels and 14 consonants Wrote on leaves and barks of trees using colored saps of tress as ink and pointed sticks as pencils Literature : Ifugao epic - Hudhud (glorifies Ifugao history and its hero Aliguyon) and the Alim( resembles the Indian gods in the epic Ramayana) Ilocano epic - Biag ni Lam-ang Bicolano epic – Handiong Muslim epics - Bantugan, Indarapatra & Sulayman, Bidasari, Parang sabil Salawikain, bugtong, kasabihan Filipino Language Derived from Tagalog dialect It became official in 1987 Christian Doctrine was the first book written in Tagalog which was in Baybayin script. Development of the Language : 1. Alibata / Baybayin – 3 vowels & 14 consonants (17 letters) 2. Lumang Alpabeto (Abakada) – 5 vowels & 15 consonants - 20 letters 3. -

Malay Self-Taught by the Natural Method : with Phonetic Pronunciation

l-^ t 1 i*UM«WIMIM«Hk« A LAY ASIA C^Lp|AOGHr S PRONONCiAttON Elchentary Grammar, Vocabularies, Travel-Talk, Mining & RUB 8ER-PLA?>>f»NG. MoNEY.WEiGiifs ^ Measures. > ^HarfKroii^li ^ (3^ Lqnp© PL 3loS A I as CORNELL UNIVERSITY LffiRARIES ITHACA. N. Y. 14853 John M. Echols CoUeaion on Southeast Asia JOHN M. OLIN LIBRARY Library Cornell university Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92401 1 084948 , Marlborough's Self-Taught Series. maiap $eif=Caugi)t By the Natural Method. Phonetic Pronunciation. THIMM'S SYSTEM ABDUL MAJID, Acting Headmaster, Malay Training College, Matang. Author of "Vocabulary and Grammar for B^gjnnej^"], "jRaK^ " Mengajar", Anak-kunchi Pengetahuan '*. Translator of Phillips' "Geography and History of the Malay Peninsula". (r c, ft' PZ i In LONDON: ^ , E. MARLBOROUGH & CO.. 51/)ld Bailey. E.C.4. 1920. '\/''Orj ^'^'Jliln , n ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. A Be&icateD to His Excellency the Hon. Mr. RICHARD JAMES WILKINSON! C.M.G., Governor of Sierra Leone, West Africa, WHO, AS Inspector of Schools, F.M.S., . in 1904, INITIATE!? THE MALAY COLLEGE, Kuala Kangsar, where I received my HIGHER EDUCATION, BOTH IN ENGLISH ANI> IN Malay. A. M. PREFACE. ""THE Malay language is spoken not only in the Malay Peninsula, but also at most of the principal towns and ports in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, with just such a slight variation in different places as not to make a Malay of one place totally helpless in another. -

Simplified Grammars

TRUBNER'S COLLECTION OF SIMPLIFIED GRAMMARS OP THE PRINCIPAL ASIATIC AND EUROPEAN LANGUAGES. EDITED BY REINHOLD ROST, LL.D., PH.D. IX. OTTOMAN TURKISH. BY J. W. REDHOUSE. TRUBNER'S COLLECTION OF SIMPLIFIED GRAMMARS OF THE PRINCIPAL ASIATIC AND EUROPEAN LANGUAGES. EDITED BY REINHOLD ROST, UJ.D., PH.D. I. HINDUSTANI, PERSIAN, MODERN GREEK. AND ARABIC. BY E. M. GELDABT, M.A. Price 2s. 6d. BY THE LATE E. H. PALMEE, M.A. VI. Price 5s. ROUMANIAN. BY R. TORCEANU. II. Price 5s. HUNGARIAN. VII. BY I. SINGES. TIBETAN. Price 4s. 6d. BY H. A. JASCHZE. Price 5s. III. BASQUE. VIII. BY W. VAN EYS. DANISH. Price 3s. 6d. BY E. C. OTTE. Price 3s. 6d. IV. IX. MALAGASY. OTTOMAN TURKISH. BY G. W. PABKEE. BY J. W. REDHOUSE. Price 5s. Price 10s. 6d, Grammars of the following are in preparation .— Albanese, Anglo-Saxon, Assyrian, Bohemian, Bulgarian, Burmese, Chinese, Cymric and Gaelic, Dutch, Egyptian, Finnish, Hebrew, Kurdish, Malay, Pali, Polish, Russian, Sanskrit, Serbian, Siamese, Singhalese, Swedish, &c, &c, &c. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., LUDGATE HILI. SIMPLIFIED GRAMMAR OF THE OTTOMAN-TURKISH LANGUAGE. BY J. W. REDHOUSE, M.R.A.S., HON. MBMBER OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LITERATURE LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., LUDGATE HILL. 1884. [All rights reserved.] LONDON: GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, LIMITED, BT. JOHN'S SQUARE, CLERKENWELL ROAD. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE Preface . ix Note on Identity of Alphabets ..... xii CHAPTER I. LETTERS AND ORTHOGRAPHY. SECTION I. Number, Order, Forms, and Names of Letters . ..... 1 Synopsis of Arabic, Greek, and Latin Letters . 4 „ II. Phonetic Values of Letters, Vowel-Points, Orthographic Signs, Transliteration, Ottoman Euphony . -

The Arabluatex Package V1.20 – 2020/03/23

The arabluatex package v1.20 – 2020/03/23 Robert Alessi [email protected] Contents License and disclamer 3 4.3 Special orthographies . 21 The name of God 21 The 21 ا ّلََ يِذ Introduction 3 conjunctive 1 1.1 arabluatex is for LuaLATEX..... 5 4.4 Quoting . 22 novoc 22 voc 23 fullvoc 2 The basics of arabluatex 5 23 2.1 Activating arabluatex ........ 5 4.4.1 Quoting the hamzah .... 23 Font setup 5 4.5 The ‘pipe’ character (|) . 24 2.2 Options . 6 4.6 Putting back on broken contextual 2.2.1 Classic contrasted with analysis rules . 24 modern typesetting of Arabic 6 4.7 Stretching characters: the taṭwīl . 26 2.3 Typing Arabic . 8 4.8 Digits . 26 2.3.1 Local options . 9 4.8.1 Numerical figures . 26 4.8.2 The abjad ......... 26 3 Standard ArabTEX input 9 4.9 Additional characters . 27 3.1 Consonants . 9 4.10 Arabic emphasis . 28 3.2 Additional characters . 11 4.10.1 Underlining words or num- 3.3 Vowels . 11 bers . 28 3.3.1 Long vowels . 11 3.3.2 Short vowels . 12 5 Arabic poetry 28 Scaling and distortion of 4 arabluatex in action 13 characters 31 Footnotes 31 4.1 The vowels and diphthongs . 13 Line numbering 31 Short vowels 13 Long vow- 5.1 Example . 32 els 13 ʾalif maqṣūrah 13 ʾalif otiosum 14 ʾalif maḥḏū- 6 Special applications 33 fah and defective ū, ī 14 Linguistics 33 Brackets 33 ʿAmr un, and Additional Arabic marks 34 14 ي/و Silent -tanwīn 14 The ‘Zero width joiner’ char 14 و the silent 4.2 Other orthographic signs . -

'How Bòsò Walikan Malangan Complies to Javanese Phonology'

How Bòsò Walikan Malangan complies to Javanese phonology Nurenzia YANNUAR Leiden University and Universitas Negeri Malang A. Effendi KADARISMAN Universitas Negeri Malang Bòsò Walikan Malangan ([bɔsɔ waliʔan malaŋan]), hereafter Walikan, is an Indonesian youth language that originated as a secret code among guerilla fighters. Walikan in Javanese means ‘reversed’, as it mixes words originating from the Malangan dialect of Javanese as well as the local variety of Indonesian and reverses them into distinct lexical forms that cannot easily be deciphered by non-speakers of Walikan. This paper examines the different reversal processes through the lenses of phonology and phonotactics. We analyze a selection of Walikan words pronounced by two speakers of Walikan. The results show that word reversal in general complies with Javanese phonology and phonotactics. Our research is intended to serve as a springboard towards a fuller understanding of the reversal rules in Walikan. 1. Introduction1 Language manipulation has been a common strategy to conceal messages in different languages (Bagemihl 1989, Conklin 1956, Lefkowitz 1991, Storch 2011). It can be done through many ways, for instance the addition or reversal of syllables, the deletion of certain sounds, and the creation of language metaphors (Storch 2011:19). From secret languages, these language registers can then develop into popular language games, and subsequently as the ‘cool language’ of young people (urban youth language). In Java, Indonesia, there are two popular reversed languages which developed from secret languages that are now seen as integral parts of youth culture. Bòsò Walikan Yogyakarta in Central Java is part of the identity of the hip-hop community in Yogyakarta (Nugraheni 2016), while Bòsò Walikan Malangan in East Java has become the language of solidarity and regional pride spoken by the people of Malang (Hoogervorst 2014, Yannuar 2018). -

PROCEEDINGS the 5Th LITERARY STUDIES CONFERENCE

―Textual Mobilities: Diaspora, Migration, Transnationalism and Multiculturalism‖ | PROCEEDINGS The 5th LITERARY STUDIES CONFERENCE “Textual Mobilities: Diaspora, Migration, Transnationalism and Multiculturalism” 12-13 October 2017 Advisory Board: Dr. Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, M.Hum. Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. Elisabeth Arti Wulandari, Ph.D. (English Letters Department, Universitas Sanata Dharma, Indonesia) Dr. Novita Dewi, M.S., M.A. (Hons.) Paulus Sarwoto, Ph.D. (Graduate Program in English Language Studies, Universitas Sanata Dharma, Indonesia) Prof. Carla M. Pacis (Department of Literature, De La Salle University, Philippines) Assoc. Prof. Amporn Sa-ngiamwibool, Ph.D. (English Department, Shinawatra University, Thailand) Ivan Stefano, Ph.D. (Department of Education, Ohio Dominican University, United States) with a Preface by Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. (Universitas Sanata Dharma, Indonesia) Editors: Stephanie Permata Putri Harris Hermansyah Setiajid Hosted by English Letters Department Graduate Program in English Language Studies Universitas Sanata Dharma, Yogyakarta, Indonesia in cooperation with Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines Fakultas Sastra Universitas Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta 2017 Literary Studies Conference 2017 | 1 PROCEEDINGS LITERARY STUDIES CONFERENCE 2017 | ISBN: 978-602-60295-9-1 PROCEEDINGS The 5th LITERARY STUDIES CONFERENCE 2017 “Textual Mobilities: Diaspora, Migration, Transnationalism, and Multiculturalism” Copyright ©2017 Fakultas Sastra Universitas Sanata Dharma Published by Fakultas