How Empathic Is Your Healthcare Practitioner? a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Patient Surveys J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

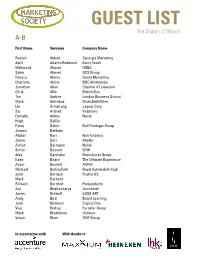

GUEST LIST the Shard | 12 March A-B

GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March A-B First Name Surname Company Name Russell Abbott Synergis Marketing April Adams-Redmond Kerry Foods Mahmood Ahmed HSBC Salim Ahmed GCS Group Rebeca Alamo Quant Marketing Charlotte Aldiss BBC Worldwide Jonathan Allan Channel 4 Television Chris Allin British Gas Tim Ambler London Business School Mark Antrobus GlaxoSmithKline Ian Armstrong Jaguar Cars Saj Arshad Vodafone Danielle Atkins Nokia Hugh Baillie Patsy Baker Bell Pottinger Group Joanna Baldwin Alistair Barr Barr Gazetas Jayne Barr Abellio Adrian Barragan Nokia Simon Bassett EMR Alex Batchelor BrainJuicer Group Katie Beard The Ultimate Experience Adam Beckett AVIVA Michael Bedingfield Royal Automobile Club John Bernard Firefox OS Mark Bernard Richard Bernholt Periproducts Joy Bhattacharya Accenture James Bidwell CASS ART Andy Bird Brand Learning John Birkbeck Capital One Viya Bishay Eurostar Group Mark Bleathman Unilever Vivian Blom TMF Group In association with With thanks to GUEST LIST The Shard | 12 March B-C First Name Surname Company Name Chris Bowry Eurostar Group Emma Bradley BBC Nick Bradley City & Guilds Colin Bradshaw Rapp Russell Braterman Vodafone Francesca Brosan Omobono Lorna Brown John Lewis Lucas Brown Total Media Group Pamela Brown British Gas Rob Bruce Whyte & Mackay Kevin Bryant E.ON UK Richard Burdett Horse & Country TV Matt Burgess Unilever Hugh Burkitt The Marketing Society Ivor Burns Camelot UK Lotteries Joanna Burton Crescent Communications Amanda Campbell Capital Shopping Centres David Campbell World Brands Limited Dominic -

FIPP Management Board As at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi

FIPP Management Board as at 21 March 2019 Chairman Ralph Büchi, Chief Operating Officer of the Ringier Group & CEO of Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Switzerland Treasurer Erwin Fidelis Reisch, President & CEO, Alfons W. Gentner Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Germany President & CEO, James Hewes, President & CEO, FIPP - the network for global media, UK Directors Kaisa Ala-Laurila, CEO, A-lehdet Oy, Finland Srinivasan Balasubramanian, Managing Director, Ananda Vikatan Publishers Private Limited, India Natasha Christie-Miller, Divisional CEO, Ascential, Ascential, UK Enrique Micheli, Executive Director, Asociación Argentina de Editores de Revistas (AAER), Argentina Yolanda Ausín Castañeda, General Manager, Asociación de Revistas de Información (ARI), Spain Julia Raphaely, CEO, Associated Media Publishing, South Africa Jan Bayer, Member of the Executive Board & President News Media, Axel Springer SE, Germany Andrew Moultrie, Director of Consumer Products, Publishing and Web Properties, UK, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Helen O'Donnell, Head of Development, TalentWorks, BBC Studios Distribution Limited, UK Alfred Heintze, COO, Burda International Holding GmbH, Germany Wu Shangzhi, President, China Periodicals Association (CPA), China Pierre Lamunière, President & Chairman, Edipresse Group, Switzerland Porfirio Sánchez Galindo, CEO, Editorial Televisa S.A. de C.V., Mexico Aaron Asadi, Chief Operations Officer, Future Publishing Ltd, UK Rolf Heinz, President & CEO Prisma Media, President G+J International -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 1907301 11/01/2010 Address for Service in India/Attorney Address

Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 1907301 11/01/2010 VINOD KHODARIA 144 A, IIND FLOOR, KATRA MASHROO, DARIBA KALAN, DELHI - 110006 SERVICES & CONSULTANCY PROVIDER INDIAN Address for service in India/Attorney address: BALAJI IP PRACTICE E-617 STREET NO- 11&12 WEST VINOD NAGAR I.P. EXTN. NEW DELHI-110092 Used Since :01/01/2010 DELHI ADVERTISING. BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS 4113 Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 2080096 04/01/2011 SMT. INDERJEET KAUR 532 - D - I, MERCHANT CHAMBER BUILDING, SADAR BAZAR, AGRA CANTT. AGRA, U.P SERVICES Address for service in India/Agents address: P. K. ARORA TAJ TRADE MARKS PVT. LTD, 110 ANAND VRINDAVAN SANJAY PLACE AGRA(U.P) Used Since :01/01/1990 DELHI ADVERTISING, MARKETING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICIAL FUNCTIONS & FRANCHISE DISTRIBUTION RELATING TO EDUCATION, PROVIDING OF TRAINING DANCE & MUSLCAI CLASSES, ENTERTAINMENT; SPORTING AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES INCLUDING ORGANIZING AND PRESENTING CONCERTS, FESTIVALS, MUSICAL PROGRAMMES INCLUDING GIDDHA, BHANGRA, PUNJABI CULTURAL PROGRAMME, WESTERN MUSIC, LIVE SHOWS, LIVE PERFORMANCES, D.J. SYSTEM, BAND, ORCHESTRA, SOUND SYSTEM, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND VOCALS, MUSIC AND LIGHT ARRANGEMENT, ARTISTIC EVENTS & ALL KIND OF EVENT ARRANGEMENTS, BEING INCLUDED IN CLASS - 35. THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 4114 Trade Marks Journal No: 1845 , 16/04/2018 Class 35 2128607 11/04/2011 NAMITA NAYYAR trading as ;WOMEN FITNESS E-25, NEW AGRA -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 14 December 2017) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £760 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

Tla Hearing Board

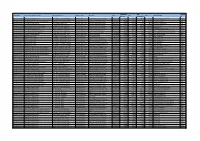

2/9/2018 Hearing Board Date wise Report TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/03/2018 to 15/03/2018 Location: MUMBAI S.No. TM Class Hearing Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Despatch Despatch No. Date Schedule No. Date 1 2676219 7 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 GLOB AL CONVEYOR SYSTEMS PRIVATE LIMITED VISHESH AND ASSOCIATES ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 12:17:41 2 2184935 9 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 MUSIC BROADCAST PRIVATE LIMITED M. K. SABOO & ASSOCIATES ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 10:56:35 3 2389793 3 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 ASSOCIATED AROMATICS PRIVATE LIMITED ARJUN T. BHAGAT & CO. ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:01:55 4 2674574 41 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 HIS HOLINESS SYEDNA MUFADDAL SAIFUDDIN ARJUN T. BHAGAT & CO. ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:30:33 5 2673955 3 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:50 6 2673957 5 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:50 7 2673959 5 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:51 8 2673954 3 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:49 9 2673958 5 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:51 10 2673961 5 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 PIRAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED ALMT LEGAL ---- 30/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 11:24:51 11 2674671 39 01/03/2018 Morning (10.30 SIMATECH SHIPPING AND FORWARDING LLC JATIN SHANTILAL POPAT. -

Register of Lords' Interests

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, National Library of Wales Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, Stephen Dodgson Trust (promotes continued awareness/performance of works of composer Stephen Dodgson) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Sesquicentenary Committee (music) Chairman and Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 8: Gifts, benefits and hospitality Two tickets and hospitality provided by Football Association to Manchester City v Watford FA Cup Final, Wembley Stadium, 18 May 2019 Guest of Vitality at the Netball World Cup, 12 July 2019; three tickets and hospitality provided * Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director and Trustee, The Atlas Foundation (registered charity; seeks to improve lives of disadvantaged people across the world) Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) President (formerly Vice President), British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the member is or will be paid to this company; see category 4(a)) Director, Visionable Limited (formerly IOCOM UK Ltd) (visual business platform) Independent Non-executive Director, Co-operative Group Board of Directors (consumer co-operative) Non-executive Director, Nuffield Health (healthcare) Category 2: Remunerated employment, office, profession etc. -

FIPP Management Board As at 12 December 2017 Chairman Ralph

FIPP Management Board as at 12 December 2017 Chairman Ralph Büchi, Chief Operating Officer, Ringier Group & CEO, Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Ringier Axel Springer Switzerland AG, Switzerland Treasurer Erwin Fidelis Reisch, President & CEO, Alfons W. Gentner Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Germany President & CEO James Hewes, President & CEO, FIPP - the network for global media, UK Officers Pierre Lamunière, President & Chairman, Edipresse Group, Switzerland Frederic Kachar, CEO & Chairman, Editora Globo S.A., Brazil Rolf Heinz, President & CEO Prisma Media, President G+J International Europe, Groupe Prisma Média, France Tom Bureau, CEO, Immediate Media Co, UK Aroon Purie, Chairman & Editor-in-Chief, The India Today Group (ITG), India Barry McIlheney, CEO, Professional Publishers Association (PPA), UK Stephan Scherzer, Chief Executive Officer, VDZ - Verband Deutscher Zeitschriftenverleger e.V., Germany Directors Kaisa Ala-Laurila, CEO, A-Lehdet Oy, Finland Srinivasan Balasubramanian, Managing Director, Ananda Vikatan Publishers Private Limited, India Yolanda Ausín Castañeda, General Manager, Asociación de Revistas de Información (ARI), Spain Julia Raphaely, CEO, Associated Media Publishing, South Africa Jan Bayer, Axel Springer SE, President BILD and WELT Group, Germany Andrew Moultrie, Director, Consumer Products & Publishing, UK, BBC Worldwide, UK Shi Feng, President, China Periodicals Association (CPA), China Porfirio Sánchez Galindo, CEO, Editorial Televisa S.A. de C.V., Mexico Natasha Christie-Miller, Divisional CEO, Ascential, UK -

About ASIFMA Annual Conference 2016

About ASIFMA Annual Conference 2016 ASIFMA Annual Conference themed ‘Developing Asia’s Capital Markets’ has been established for four successful years as the pre-eminent industry-wide, regional event for the financial community providing a unique opportunity for global and regional policy makers and high-caliber industry representatives from both sell side and buy side to meet and discuss important issues impacting the development of Asia’s capital markets. This flagship conference of ASIFMA, as a cornerstone industry event for the region, celebrated ASIFMA’s 10th anniversary in November 2016 in Singapore. The event got 400 attendees from over 200 organizations, including 10% policy maker/public official, 7% issuer/treasurer, 22% buy side and 8% media. It also received support from more than 100 speakers including senior representatives of Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC), British Embassy, Credit Guarantee and Investment Facility (CGIF), European Commission, Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), Financial Services Agency of Japan (FSA), Financial Supervisory Service of Korea (FSS), International Finance Corporation (IFC), Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand (SEC) and many other leading financial institutions. 1 We highly appreciated the highest-ever levels of support from 26 sponsoring firms including ANZ, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, BNP Paribas, BNY Mellon, CAIA , CICC, CIMB, Clearstream, Credit Agricole CIB, DBS Bank, Deutsche Bank, DTCC, Euroclear, Goldman Sachs, ING, J.P. Morgan, Lexcel Partners, Mizuho Securities, Moody's Investors Service, National Australia Bank, Nomura, PwC, Societe Generale, S&P Global Ratings, Standard Chartered Bank and Thomson Reuters, and 18 endorsers as well as 14 media partners. -

May 2021 (Pdf)

Transaction VAT Supplier Body Name Service Area Categorisation Responsible Unit Expense Type Narrative Date Net Gross Supplier Name Number reclaimable ID Broads Authority Recharged Support Costs Asset Mgmt - Careys Meadow - C Supplies & Services Topographical survey to determ 05/05/2021 701955 1450.00 290.00 1740.00 Anglia Land Surveys Limited A258 Broads Authority Recharged Support Costs Asset Mgmt-St Benets Abbey-Con Support Services Prof fees in connection with r 12/05/2021 706124 2160.00 432.00 2592.00 Leathes Prior Solicitors L241 Broads Authority Specialist Ringfenced Account (Navigation) Boat Safety - Contractor Servs Supplies & Services Filming and editing of Boating 17/05/2021 704867 2950.00 0.00 2950.00 JH Film Productions J263 Broads Authority Promoting Understanding Boat Trip-Ra-Leases Land Supplies & Services Mooring of Ra for the period 1 28/04/2021 703002 652.09 130.42 782.51 EC Landamore & Co Ltd L262 Broads Authority Conservation of Natural Environment CANAPE - WP 1b Ext Expertise - Support Services First Level Controller reports 10/05/2021 705630 1500.00 300.00 1800.00 Lees Accountants L054 Broads Authority Conservation of Natural Environment CANAPE - WP 4 Ext Expertise - Supplies & Services Wetland feasibility contract B 24/05/2021 706139 9800.00 1960.00 11760.00 Hummingbird H426 Broads Authority Promoting Understanding Communications - Subscriptions Support Services Renewal of copyright licence N 24/05/2021 706148 968.00 193.60 1161.60 NLA Media Access Limited N109 Broads Authority Conservation of Cultural Heritage -

1 Treasury Committee by 31St May VAT Submission Written Evidence

Treasury Committee by 31st May VAT Submission Written Evidence Submitted by PPA 31st May 2018. About Us The Professional Publishers Association (PPA) is the voice of the magazine sector and represents publishers and providers of consumer, customer and business media in the UK. Our membership comprises 260 companies, publishing around 2,500 consumer magazine titles, 4,500 business-to- business publications, data and information providers, and smaller independents. The PPA's membership includes the UK’s largest publishing houses, including Ascential, Bauer Media Group, Centaur, Condé Nast, Hearst, Time Inc. UK, Immediate Media, Haymarket Media Group, William Reed Business Media, as well as many smaller independent publishers. Consumer magazine brands reach 7 in 10 of the UK population every month, through globally renowned brands such as Vogue, Radio Times, The Economist, Tatler, Campaign, Grazia, NME, The Grocer, Angling Times, Top Gear, Decanter, The Big Issue, The Week, and thousands of other much-loved household names. With more than 20 million magazines sold every week in the UK, the sector is worth in excess of £4bn to the UK economy, employing 114,000 people. Summary PPA welcomes the Committee’s Inquiry on VAT and the opportunity to highlight a long-standing anomaly in the tax system that damages consumer choice, holds back innovation and investment, and fails to meet the tests set for good tax principles. VAT was introduced in the UK on 1st April 1973 at two rates, a standard rate of 10% and a zero rate on selected goods and services (such as food, children’s clothes and shoes, books, newspapers and magazines). -

Payments to Suppliers

Document Cost Centre / Subjective Body Name Supplier Name Account Number Invoice Date Cost Centre/Project Description Subjective description Invoice Amount (Excluding VAT) File Name Project Code Account Cambridge City Council 1st Glass Services 10000100 04/04/2019 027292 6207 Repairs Day to Day 60233 Housing Repairs - Work Given To External Contractors £660.96 Cambridge City Council 2 Ton Production 10/04/2019 028300 1262 Folk Festival 52210 Delivery fees £6,678.00 Cambridge City Council 2 Ton Production 10/04/2019 028297 1262 Folk Festival 52210 Delivery fees £8,024.00 Cambridge City Council 2 Ton Productions Ltd 10326600 24/04/2019 029307 1263 Cambridge Live - Central 52200 Booking Fees £3,910.00 Cambridge City Council AA Global Language Services Ltd 10001100 31/03/2019 028284 1203 Corporate Policy 62408 Translation Services £768.84 Cambridge City Council Abbey Bowls Club 10001200 24/04/2019 028957 1102 Leisure Contract Client Costs 64600 Grants And Contributions £5,331.42 Cambridge City Council ACAS 10001800 18/02/2019 027490 6203 Technical Services 62400 Consultancy Fees £1,355.00 Cambridge City Council Acting Now C I C 10002200 12/04/2019 028337 1057 Community Development Voluntary Support 64600 Grants And Contributions £2,000.00 Cambridge City Council Addex Group 10251600 29/03/2019 027959 1855 Street Cleaning - Direct 60909 Vehicle Hire £750.00 Cambridge City Council Aecom Ltd 10003200 12/04/2019 029011 300061 New Build - Hawkins Road 70010 CAPEX - Other Professional Fees £860.00 Cambridge City Council Alboro Developments Ltd 10133300