Are Functional Accounts of Goodness Relativist? David E.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Seven Study Questions

Chapter Seven Study Questions 2. Synonyms 1) change, alter, vary, modify mean to make or become different. Change implies making either an essential difference often amounting to a loss of original identity or a substitution of one thing for another <changed the shirt for a larger size>. Alter implies the making of a difference in some particular respect without suggesting loss of identity <slightly altered the original design>. Vary stresses a breaking away from sameness, duplication, or exact repetition <you can vary the speed of the conveyor belt>. Modify suggests a difference that limits, restricts, or adapts to a new purpose <modified the building for use by the handicapped>. 2) hate, detest, abhor, abominate, loathe mean to feel strong aversion or intense dislike for. Hate implies an emotional aversion often coupled with enmity or malice <hated his former friend with a passion>. Detest implies violent antipathy or dislike, but without active hostility or malevolence <I detest moral cowards>. Abhor implies a deep, often shuddering repugnance from or as if from fear or terror <child abuse is a crime abhorred by all>. Abominate suggests strong detestation and often moral condemnation <virtually every society abominates incest>. Loathe implies utter disgust and intolerance <loathed self-appointed moral guardians>. 3) repugnant, repellent, abhorrent, distasteful, obnoxious, invidious mean so unlikable as to arouse antagonism or aversion. Repugnant applies to something that is so alien to one’s ideas, principles, tastes as to arouse resistance or loathing <regards boxing as a repugnant sport>. Repellent suggests a generally forbidding or unpleasant quality that causes one to back away <the public display of grief was repellent to her>. -

Gateways to Conservation II: Grades

Gateways to Conservation II an environmental education curriculum for students in grades 6 –8 Gateways to Conservation II an environmental education curriculum for students in grades 6-8 © Audubon 2004 SECTION TITLE i Acknowledgements e appreciate the cooperation with the National Park Service's Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network Wto make the second volume of this curriculum possible. Numerous volunteers of Pickering Creek Audubon Center and teachers throughout Talbot County donated their time for this effort including: Lisa Donmoyer, Julie Harp, Mary Johnson, Janet Krones, Erney Maher, Myra McPherson, John Melton, Susan Pritchard and Jane Whitelock. The following current and past staff members of Pickering Creek Audubon Center helped create the lessons contained in this book: Stephanie Colvard, Kristen Facente, Shannon Gordon, E.B. James, Sarah Krones, Erin Poor, Kate Rogers, Mark Scallion, and Brit Slattery. Project Leader: Shannon Gordon Center Director: Mark Scallion Photographs by: Royce Ball, David Godfrey, Lindsey Goodwick, Andrew Gordon, David Menke, Susanna Scallion, Hugh Simmons, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Illustrations of Maryland fossils courtesy of James Reger, Maryland Geological Survey Layout by: Linda Rapp/Ecoprint Printed on 30% post-consumer waste paper, using wind energy and carbon neutral production methods. Pickering Creek Audubon Center is a Chesapeake Bay Gateways site—a place to explore and learn about the Chesapeake region. Visit this and other places in the Gateways Network to experience the Bay’s stories, culture, spirit and mystery. Learn about the Chesapeake Bay restoration effort and how you can contribute. Our well-being and the Bay’s health are interdependent. Visit www.baygateways.net for more information. -

Our High-Resolution Brochure

www.ultrawiztools.com UltraWiz® Original Cold Knife Blades UltraWiz® UltraThin Blades The 1000 Series The 5000 Series ® ® UltraWiz Original UltraWiz® Original Blades, To meet the demand for thinner UltraWiz UltraThin Blades "the blades that perma- blades, UltraWiz® created Blades nently changed the industry" the UltraThin Blade. They are manufactured by A.N. are 40% thinner than our Designs Inc. The 1000 Series Original Blade, surpassing its was introduced in strength and durability. 1986 and quickly 1000 vs 5000 A two-step coining became known for being consistently sharp and tough. process includes a second thinning operation UltraWiz® is preferred by the majority of technicians in prior to heat treating the blade without removing the industry because of their reliability and has become any material. UltraThin Blades out perform any other the most popular cold knife blade in the auto glass cold knife blade on the market; cutting with unequaled replacement industry. ease and lasting durability. UltraWiz® UltraWiz® Starter Blade 10 UltraThin Standard Blade 10 1000-M 5001-M 3/8" Cut Length 3/4" Cut Length Use to precut urethane Use to precut urethane Also use for narrow urethane beads UltraWiz® UltraWiz® Standard Blade 10 UltraThin Long Blade 10 1001-M 5002-M 3/4" Cut Length 1" Cut Length Use to precut urethane Our most popular cut length Also use for narrow urethane beads Use for cutting most urethane beads UltraWiz® UltraWiz® Long Blade 10 UltraThin Extended Long Blade 10 1002-M 5003-M 1" Cut Length 1 1/4" Cut Length Our most popular -

November 2017 Edition

Volume XXXV No. 11 November 2017 Montreal, QC www.filipinostar.org Gender parity but little diversity in Plante's executive comIntemrim oppiostitiotn leeader e Lionel Perez says partisanship prevailed, calling it broken electoral promise CBC News Posted: Nov 20, 2017 6:30 AM ET Last Updated: Nov 20, 2017 5:32 PM ET During the election campaign, Valérie Plante promised her executive committee would feature gender parity, diversity, and even a place for some members of the opposition. But Montreal's newly elected mayor did not hit all those targets in revealing members her 13-person executive committee this morning. There are seven men and six women, including Plante. There are not, however, any visible minorities. "It's a shortcoming, clearly, the [lack] of cultural diversity, in the city council in general," Plante said, pointing out that while visible minorities make up 30 per cent of the Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante stands with the 12 members of her executive committee Monday morning. All but one See page 4 Plante’s Executive are members of her party, Projet Montréal. (Lauren McCallum/CBC) Prince Harry to marry Meghan Markle at PWalacienaiddes poredrict Ca ‘haapspy tchluerch wienddinMg’ aat Sy t George’s Chapel for prince, 33, and American TV star, 36 (From The Guardian) Prince Harry and the church service, the music, the Meghan Markle are to marry at St flowers and the reception. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle Wider security costs, policing next May and will go on their first public and public order arrangements will be walkabout on Friday in Nottingham, the covered by the public purse, however. -

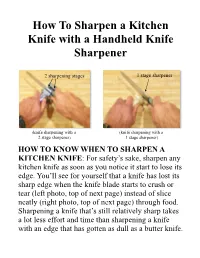

How to Sharpen a Kitchen Knife with a Handheld Knife Sharpener 3-27-21

How To Sharpen a Kitchen Knife with a Handheld Knife Sharpener 2 sharpening stages 1 stage sharpener (knife sharpening with a (knife sharpening with a ! 2 stage sharpener) 1 stage sharpener) HOW TO KNOW WHEN TO SHARPEN A KITCHEN KNIFE: For safety’s sake, sharpen any kitchen knife as soon as you notice it start to lose its edge. You’ll see for yourself that a knife has lost its sharp edge when the knife blade starts to crush or tear (left photo, top of next page) instead of slice neatly (right photo, top of next page) through food. Sharpening a knife that’s still relatively sharp takes a lot less effort and time than sharpening a knife with an edge that has gotten as dull as a butter knife. www.gotta-eat.com How To Sharpen a Kitchen Knife with a Handheld Sharpener !2 a dull blade crushes a sharp blade and tears through cuts neatly food through food Dull Knife Sharp Knife ! Needed Kitchen Knife (these directions will show how to sharpen both a short and long bladed kitchen knife) Handheld Sharpener (what you see below are only two examples of handheld sharpeners – how to use both is shown in the following directions) 2 stage sharpener 1 stage sharpener ! www.gotta-eat.com How To Sharpen a Kitchen Knife with a Handheld Sharpener !3 1. Hold the knife comfortably in your hand as if you were going to cut with it as shown below whether you’re using a long bladed (left photo) or short bladed knife (right photo) below. -

Cutlery, Barware/ Holloware, Accessories & Chef's Knives

Cutlery, Barware/ Holloware, Accessories & Chef’s Knives Contents Robert Welch 4 Folio 80 Cutlery .............................. 8 Cutlery .............................. 80 Ammonite ........................... 10 Whitfield ............................. 82 * Arden ................................. 12 Carolyn .............................. 83 * Ashbury .............................. 14 Logan ................................. 84 * Baguette ............................. 16 * Hartman ............................. 85 * Bergen ............................... 18 Alison ................................. 86 * Bourton .............................. 20 Bryce .................................. 87 * Bud .................................... 22 * Pirouette ............................. 87 * Contour Noir ....................... 24 * Deta ................................... 26 Hidcote .............................. 28 Varick 88 Honeybourne ...................... 30 * Cutlery .............................. 88 Iona ................................... 32 * Avery .................................. 90 * Kingham ............................. 34 * Estate ................................. 91 * Malvern .............................. 36 * Marnee............................... 92 * Norton ............................... 38 Avina .................................. 93 * Palm ................................... 40 Distressed Briar ................... 94 * Quinton .............................. 42 Fulton Vintage Copper ......... 95 * Radford ............................. -

Knewslettter

KNIFEOKCA 39th Annual SHOW • April 12-13 Lane Events Center EXHIBIT HALL • Eugene, Oregon April 2014 Our international membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” YOU ARE INVITED TO THE OKCA 39th ANNUAL KNIFE SHOW & SALE April 12 - 13 * Lane Events Center & Fairgrounds, Eugene, Oregon In the super large EXHIBIT HALL. Now 360 Tables! ELCOME to the Oregon Knife Collectors demonstrations on Saturday. This year we have Anyone can enter to bid in the Silent Auction. See WAssociation Special Show Knewslettter. Blade Forging, Flint Knapping, quality Kitchen the display cases at the Club table to make a bid On Saturday, April 12, and Sunday, April 13, we Cutlery seminar, Knife Handle Designs, Martial on some extra special knives . want to welcome you and your friends and family Arts, Scrimshaw, Self Defense and Sharpening Along the side walls, we will have twenty to the famous and spectacular OREGON KNIFE Knives. three MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND SHOW & SALE. Now the Largest organizational Don’t miss the FREE knife identifi cation and CUTLERY COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY for Knife Show East & West of the Mississippi River. appraisal by Tommy Clark from Marion, VA your enjoyment and education, in addition to our The OREGON KNIFE SHOW happens just (Table N01) - Mark Zalesky from Knoxville TN hundreds of tables of hand-made, factory and once a year, at the Lane Events Center EXHIBIT (Table N02) and Mike Silvey on military knives antique knives for sale. Now 360 tables! When HALL, 796 West 13th Avenue in Eugene, Oregon. is from Pollock Pines CA (Table J14). -

Consumer Decision Making Skill-A-Thon Food & Cooking ID

Consumer Decision Making Skill-a-thon Food & Cooking ID Answer Sheet Appliances _____ Meat Platter _____ Chopsticks _____ Air Fryer _____ Napkin Ring _____ Citrus Reamer _____ Blender _____ Parfait Cup _____ Decorative Slicer-Ripple _____ Electric Pressure Cooker _____ Pepper Mill _____ Egg Separator _____ Food Processor _____ Punch Bowl _____ Egg Slicer _____ Ice Cream Maker _____ Saucer _____ Egg Timer _____ Immersion Blender _____ Tea Pot _____ Fat Separator _____ Mixer, Countertop _____ Flour Sifter _____ Mixer-Hand Spices/Foods _____ Garlic Press _____ Rice Cooker _____ Allspice _____ Grater _____ Skillet, Electric _____ Anise _____ Grill Brush _____ Slow Cooker _____ Basil _____ Herb Scissors _____ Tea Kettle _____ Bay Leaves _____ Kitchen Fork _____ Toaster _____ Bulgar _____ Liquid Measuring Cup _____ Toaster Oven _____ Chives _____ Mandolin Slicer _____ Turkey Fryer _____ Cilantro _____ Measuring Cups _____ Waffle Iron _____ Cinnamon _____ Measuring Spoons _____ Cloves _____ Meat Tenderizer Cookware _____ Couscous _____ Melon Baller _____ Baking Pan _____ Cumin _____ Mezzaluna _____ Baking Sheet _____ Curry Powder _____ Mixing Bowl _____ Broiler Pan _____ Dill _____ Molcajete _____ Colander _____ Garlic _____ Nut Chopper _____ Double Boiler _____ Ginger _____ Paring Knife _____ Dutch Oven _____ Mace _____ Pasta Measurer _____ French Press _____ Mustard _____ Pasta Server _____ Frying Pan _____ Nutmeg _____ Pastry Blender _____ Pastry Press _____ Oregano _____ Pastry Brush _____ Pie Plate _____ Paprika _____ Pie/Cake Server _____ -

05.Sam Rockwell.Lyt 3/9/07 7:14 PM Page 3 ID #6 05.Sam#62 Rockwell.Lyt 3/9/07 7:14 PM Page 4

05.Sam#60 Rockwell.lyt 3/9/07 7:13 PM Page 2 05.Sam Rockwell.lyt 3/9/07 7:14 PM Page 3 ID #6 05.Sam#62 Rockwell.lyt 3/9/07 7:14 PM Page 4 T h e re ’s make - b e l i eve, and then there is making someone believe. Sam Ro c k well is a pra c t i t i oner of the fo rmer and a virtuoso at the lat t e r. In his powe r, even the most mundane objects can become animated, even life- t h r e at e n i n g. Ta ke the butter knife. A few seconds ag o, it was being a bu t t e r k n i f e, spreading cholesterol on a piece of toast. Then Ro ck well decided he wanted to use it to illustrate kali, the Filipino fighting style Matt Damon uses in The Bourne Identity by wh i ch the enemy is slow ly and painfully torn ap a rt. A sudden light fli ck of the wrist and—wat ch out!—it is a bl o o d - seeking shiv that ’s coming terr i f y i n g ly close to your wrist. H aving spent 36 ye a rs on planet Earth, Ro ck well knows all kinds of d e- fense move s. If he were to be mu gged today after breakfast at Life Café in N ew York City’s East Vi l l ag e, he would have a plan of at t a ck. -

Robert Welch Designs We’Ve Been Considering the Diner for Over 60 Years, Perfecting That first Point of Contact Between Diner and Food

The comfort and feel of cutlery is a major part of the dining experience. At Robert Welch Designs we’ve been considering the diner for over 60 years, perfecting that first point of contact between diner and food. We create beautiful products that let customers focus on what matters most – enjoying the best culinary experience at your restaurant. 02 03 An exquisitely crafted knife cuts effortlessly through a succulent steak. 04 05 A perfectly weighted fork twirls spaghetti with ease. 06 07 An elegant spoon fits perfectly in hand as dessert is savoured. 08 09 Contents Our Cutlery Collections To The Table 12 68 Gourmet Dining 69 Baguette Vintage 16 Afternoon Tea 70 * Bergen 18 Buffet and Serving 71 Cheese and Fruit Platter Robert Welch Designs’ spoons and forks are made using the highest quality 18/10 stainless steel. Bourton 20 Specially hardened stainless steel provides our knife blades with the finest cutting edge. Hidcote 22 72 The Individual Touch 24 74 Raising the Bar Three distinct categories exist within the Robert Welch Designs Cutlery Collection. Kingham Malvern 26 76 Time for Tea * Quinton 28 78 Keep it Flowing Trattoria 30 80 At your Service 82 Flavour with Flair Arden 32 84 Table Accents Bud 34 Deta 36 88 Chefs’ Arena Honeybourne 38 90 Technical Specification Iona 40 91 Manufacturing Process Norton 42 92 Chef’s Knives Collection 3.5 Collection 5.0 Master Collection Palm 44 93 Santoku Knives All patterns are made from All ranges feature For customers who want Radford 46 94 Prep Knives 3.5mm stainless steel, a exceptional balance something special: Our RW2 50 95 Steak and Pizza Knives slightly thinner gauge that and comfort and are a highest levels of design and 96 Carving Knives and Forks gives this collection a lighter heavier gauge – a quality manufacture expertise, to * Skye 52 97 feel in the hand. -

Donations to and Purchases for the Museum, 1978-80

Donations to and Purchases for the Museum, 1978-80 1978-9 Donations 1 Finds from the Island of Coll, including pebble 'limpet-hammers', flints, sherds of beaker, iron- lated an r e potteryag hammerstond an , e from Sorisdale (NM 273638); beake latd ean r iron r medievao e ag l sherds from Cornai 243633M g(N ; 235627 Cornaigmord )an 244832)M e(N ; r lateo iroe r nag sherd Achaidn sa froFealn 149550)n 183545M M mBe Du (N h l(N d an ). By J CRAWFORD, Edinburgh. 2 Flint flakes from Allt Locha Ceardacha nn , Loch 755686)ShieM (N l Dahd ,an l House, Polloch, Glen Finnan, Fort William, Inverness-shir 788683)M e(N . Sherds, possibly dark age, from Loch Mudle, Ardnamurchan, Argyl 549661)M l(N . Norse grass-tempered sherd medievad san l sherds from Freswick Links, Caithness. Flint flakes, sherd f hand-madso e pottery; sherdf so stoneware bronza f o n e pi ;brooch , (medieva r later)o l Charleo tw ; I s'Stirling ' turnerd san other objects from Achnahaird Sands, Achiltibuie, Wester Ross (NC 016131). By J E KTRBY, Polloch. 3 Chert and flint flakes from near the standing stone (c NT 139354), near Drumelzier, Peebles. By Mr and Mrs R HurcmsoN, Peebles. 4 Part of a stone axe from Traprain Law, East Lothian; a socket stone from Kaimes Hill, Mid- lothian. Sherd Norsf so e grass-tempered pottery from Freswick Sands, Robert's Haven, John O'Groat Hunad san , John O'Groats, Caithness fragmento ;tw steatitf so e vessels from Freswick MURRAYS Sands R y B . -

Collection 2014/2015

COLLECTION 2014/2015 Contents TABLEWARE 5 Grand Cru Soft 6 Grand Cru 20 Grand Cru Outdoor 44 KITCHENWARE 49 Melamine 50 Bamboo 52 Knives 54 Oven-proof dishes 56 Grinders & accessories 62 Storage 64 HOMEWARE 67 Filigran 68 Saga 73 Grand Cru 74 TABLEWARE 7 Grand Cru Soft – for a relaxed everyday meal or for full course dinners. Set the scene in limitless ways by settinG the table with the Grand Cru Soft porcelain and Glass collection, introducinG soft curves to every meal from breakfast to a dinner for Guests. In its brilliant white porcelain version, the ripples stand out even more, while the soft curves of the plates, cutlery, bowls, tumblers and cups gently envelop the occasion, calling attention to what it’s really all about, namely, food and drinks. 8 With its soft curves, the Soft desiGn ensures a perfect Grip for hot drinks, and in true café style, the cup is available in two sizes: 22 cl for black “Americano” coffee and a larGer cup for “latte” and “chai” people, who can’t get by without their milk. The half-litre milk juG holds plenty of milk for several cups, perhaps with a little cane suGar added from the new suGar bowl, which is, naturally, just the thinG for chocolates and other sweet treats, too. For THE COFFEE TABLE For THE HOME BARISTA BrewinG coffee has almost become a complete science. There are so many thinGs that Go into the taste of a cup of coffee. For the practiced barista, it’s about how finely the beans are Ground, the water temperature, the amount of time the coffee is in contact with the water, and many other factors.