A Contingent Valuation Approach for Bolgoda Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolutionof Coastallaridformsinthe Western Part of Srilanka

HiroshimaHiroshimaGeographicalAssociation Geographical Association Geographical Sciences vol, 43 no.1 pp, 18-36, 1988 Evolution of Coastal Laridforms inthe Western Part of Sri Lanka JINADASA KATUPOTHA* Key Words:evolution of coastal landforms, SriLanka, late Pleistocene, Holocene, landfOmi classMcation Abstract Geomorphic and geologic evidence shows four different stages {Stage I-IV} in the evolution of coastal landforrns on the west coast of Sri Lanka during the Iate Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs. The author assumes that the old ridges in Stage I at Sembulailarna, Kiriyanl(ailiya, Pambala, Wiraliena, Uluambalarna and Kadrana areas have been fonned precedng the Holocene transgression. Low hMs and ridges in the area were coated mainly by wind blown sand, fonowing the lower sea levels during the Late Pleistocene and Earty Holocene Epochs. Radiocarbon datings en the west and seuth coast$ reveal that the sea level remained 1rn or more above the present sea level between 6170± 70 and 535e± 80 yr B. P. During this transgression, the forTner drainage basins were submerged and headland bay beaches were ereated. Many wetlands aiid beach ridges, particularly in Stages ll, III, and IV were gradualy formed owing to rninor oscMations of sea levet after mid-Holocene. Most of these landiorTns haveaclose relationship with main climatic zenes of the country. 1987; Katupotha, 1988) also help to deterrnine their I. Introduction evolution. The island of Sri Lanka has a coastline over Coastal Iandform maps of the study area were 1920 km in length, exhibiting a diversity of coastal cornpiled by means of interpretation of aerial photo- landromis. The coastal lowlands with elevation graphs (1:40,OOO-Survey Department of Sri Lanka, from mean sea level (MSL) to 30m consist of 1956) and field observations. -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

Hotspots of Land Use/Land Cover Change Around Bolgoda Wetland, Sri Lanka

J.Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2020 48 (3): 219 - 226 DOI: DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v48i3.9376 RESEARCH ARTICLE Hotspots of land use/land cover change around Bolgoda wetland, Sri Lanka AHLCM Athapaththu *, Deepthi Wickramasinghe and MGMC Somachandra Department of Zoology and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Colombo, Colombo. Submitted: 15 August 2019; Revised: 21 January 2020; Accepted: 23 March 2020 Abstract: Wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems habitats are particularly important for livelihood of the in the world. Urban wetlands are increasingly aff ected by communities who live in the area. For instance, fi sheries population growth and developmental activities. A buff er and tourism are dependent on wetlands (Gachhadar region of 60 m from the Bolgoda lake boundary was gazetted et al ., 2004). Ecosystem services provided by wetlands as an Environmental Protection Area (EPA) by the Central include absorption of pollutants, carbon sequestration, Environmental Authority in 2009 as it is the largest freshwater wetland in Sri Lanka. This study attempts to quantify the land groundwater recharge, and disaster mitigation (Chmura use changes during the period of 2001 to 2019 using GIS and et al ., 2003; Chen et al ., 2008; Ramsar Convention to identify the ‘hot spots’ where a signifi cant change in land use Secretariat, 2014). Yet human induced land use/land occurred. Land use/land cover (LULC) changed in the Bolgoda cover (LULC) changes aff ect the wetlands worldwide wetland area disproportionately. The greatest proportion of as well as services provided by them (Zhao et al ., 2004; loss of natural area was observed in dense vegetation, where a Zorrilla-Miras et al ., 2014). -

The Effect of Water Bodies As a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form

The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka The Effect of Water Bodies as a Determinant Force in Generating Urban Form. A Study on Creating a Symbiosis between the two with a case study of the Beira Lake, City of Colombo. K. Pradeep S. S. Fernando. 139404R Degree of Masters in Urban Design 2016 Department of Architecture University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka THE EFFECT OF WATER BODIES AS A DETERMINANT FORCE IN GENERATING URBAN FORM - WITH A STUDY ON CREATING A SYMBIOSIS BETWEEN THE TWO WITH A CASE STUDY OF THE BEIRA LAKE, CITY OF COLOMBO. Water bodies present in Urban Contexts has been a primary determinant force in the urban formation and settlement patterns. With the evolutionary patterns governing the cities, the presence of water bodies has been a primary generator bias, thus being a primary contributor to the character of the city and the urban morphology. Urban form can be perceived as the pattern in which the city is formed where the street patterns and nodes are created, and the 03 dimensional built forms, which holistically forms the urban landscape. The perception of urban form has also been a key factor in the human response to the built massing, and fabric whereby the activity pattern is derived, with the sociological implications. DECLARATION I declare that this my own work and this dissertation does not incorporate without acknowledgment any material previously submitted for a Degree or Diploma in any University or any Institute of Higher Learning and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any materials previously published or written by another person except where acknowledgement is made in the text. -

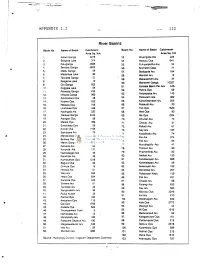

River Basins

APPENDIX I.I 122 River Basins Basin No Name of Basin Catchment Basin No. Name of Basin Catchment Area Sq. Km. Area Sq. Km 1. Kelani Ganga 2278 53. Miyangolla Ela 225 2. Bolgoda Lake 374 54. Maduru Oya 1541 3. Kaluganga 2688 55. Pulliyanpotha Aru 52 4. Bemota Ganga 6622 56. Kirimechi Odai 77 5. Madu Ganga 59 57. Bodigoda Aru 164 6. Madampe Lake 90 58. Mandan Aru 13 7. Telwatte Ganga 51 59. Makarachchi Aru 37 8. Ratgama Lake 10 60. Mahaweli Ganga 10327 9. Gin Ganga 922 61. Kantalai Basin Per Ara 445- 10. Koggala Lake 64 62. Panna Oya 69 11. Polwatta Ganga 233 12. Nilwala Ganga 960 63. Palampotta Aru 143 13. Sinimodara Oya 38 64. Pankulam Ara 382 14. Kirama Oya 223 65. Kanchikamban Aru 205 15. Rekawa Oya 755 66. Palakutti A/u 20 16. Uruhokke Oya 348 67. Yan Oya 1520 17. Kachigala Ara 220 68. Mee Oya 90 18. Walawe Ganga 2442 69. Ma Oya 1024 19. Karagan Oya 58 70. Churian A/u 74 20. Malala Oya 399 71. Chavar Aru 31 21. Embilikala Oya 59 72. Palladi Aru 61 22. Kirindi Oya 1165 73. Nay Ara 187 23. Bambawe Ara 79 74. Kodalikallu Aru 74 24. Mahasilawa Oya 13 75. Per Ara 374 25. Butawa Oya 38 76. Pali Aru 84 26. Menik Ganga 1272 27. Katupila Aru 86 77. Muruthapilly Aru 41 28. Kuranda Ara 131 78. Thoravi! Aru 90 29. Namadagas Ara 46 79. Piramenthal Aru 82 30. Karambe Ara 46 80. Nethali Aru 120 31. -

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka Central Environmental Authority National Wetland Directory of Sri Lanka This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and printing of this document was carried out with the financial assistance of the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Sri Lanka. i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI. This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and publication of this directory was undertaken with financial assistance from the Royal Netherlands Government. Published by: The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Copyright: © 2006, The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the International Water Management Institute. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

1. Metro Colombo Urban Development Project

1. Metro Colombo Urban Development Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Screening Report for Construction of bank protection walls of Beira Lake and Rehabilitation of McCallum lock gates Final Report December 2011 Uni‐Consultancy Services University of Moratuwa Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Table of Contents 1. Project Identification 3 2. Project Location 3 3. Project Justification 5 4. Project Description 7 5. Description of the Existing Environment 11 6. Public Consultation 19 7. Environmental Effects and Mitigation Measures 7a. Screening for Potential Environmental Impacts 21 7b. Environmental Management Plan 29 8. Conclusion and Screening Decision 43 9. Screening Decision Recommendation 52 10. EMP implementation responsibilities and costs 53 11. Details of Persons Responsible for the Environmental Screening 55 Annexes 1. Photographs of some of the important locations along project roads 2 URBAN UPGRADING WORK Metro Colombo Urban Development Project Environmental Screening Report 1. Project Identification Project title 1. Construction of bank protection walls of the Beira Lake and 2. Rehabilitation of McCallum lock gates Project Urban Development Authority Proponent 2. Project Location Location Location of the project is shown in the Figure 1. Definition of The project area is along some stretches of the Beira Lake banks as shown in Project Area Figure 1 and the McCallum Lock Gates located next to the Convention Centre (DR Wijewardena Mawatha). (The geographical The bank protection wall to be constructed commences from the end of Fire extent of the Department premises of the Air Force and continues up to Hyde Park Corner, the project & areas other portion of the proposed protection wall commences from Northern Bank of affected during the West Lake and continues up to Western Bank of the West Lake. -

Y%S ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;%Sl Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H W;S Úfyi the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY

Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 2072$58 - 2018 uehs ui 25 jeks isl=rdod - 2018'05'25 No. 2072/58 - FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2018 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) — GENERAL Government Notifications SRI LANKA Coastal ZONE AND Coastal RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN - 2018 Prepared under Section 12(1) of the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act, No. 57 of 1981 THE Public are hereby informed that the Sri Lanka Coastal Zone and Coastal Resource Management Plan - 2018 was approved by the cabinet of Ministers on 25th April 2018 and the Plan is implemented with effect from the date of Gazette Notification. MAITHRIPALA SIRISENA, Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment. Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment, No. 500, T. B. Jayah Mawatha, Colombo 10, 23rd May, 2018. 1A PG 04054 - 507 (05/2018) This Gazette Extraordinary can be downloaded from www.documents.gov.lk 1A 2A I fldgi ( ^I& fPoh - YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2018'05'25 PART I : SEC. (I) - GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 25.05.2018 CHAPTER 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE SCOPE FOR COASTAL ZONE AND COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 1.1.1. Context and Setting With the increase of population and accelerated economic activities in the coastal region, the requirement of integrated management focused on conserving, developing and sustainable utilization of Sri Lanka’s dynamic and resources rich coastal region has long been recognized. -

Part I : Introduction

PART I : INTRODUCTION Final Report, Volume II Introduction Main Report Chapter 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study As the urbanized area of the Colombo Metropolitan Region (CMR) expands into the coastal lowland, the difficulty of drainage is causing an increase in the frequency of flood inundation. The inundation results in damage to property and deterioration of infrastructures as well as a worsening hygiene environment for residents. Implementation of remedial measures to reduce inundation is important to secure lands for future development in the CMR (population 5.3 million at 2001). Since the early 1990’s, the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) has been implementing the Greater Colombo Flood Control and Environment Improvement Project, being assisted by an Official Development Assistance Loan from the Government of Japan (GOJ). GOSL has also recognized the need for a comprehensive master plan for storm water drainage in the entire CMR and in September 1999 requested GOJ to undertake a study to formulate such a master plan GOJ agreed to conduct the Study on Storm Water Drainage Plan for the Colombo Metropolitan Region in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (the Study). The Scope of Work was agreed between the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation (SLLRDC) of the Ministry of Urban Development, Construction & Public Utilities (presently Ministry of Housing & Plantation Infrastructure) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) on March 7, 2001. 1.2 Objectives of the Study The objectives of the Study are: 1) To formulate a master plan for storm water drainage in the Colombo Metropolitan Region, 2) To conduct feasibility study on a priority project to be identified in the master plan, and 3) To carry out technology transfer to counterpart personnel in the course of the Study. -

Detailed Species Accounts from the Threatened Birds Of

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Fish Assemblage Structure of Two Contrasting Stream Catchments Of

The Open Conservation Biology Journal, 2011, 5, 25-44 25 Open Access Fish Assemblage Structure of Two Contrasting Stream Catchments of the Mahaweli River Basin in Sri Lanka: Hallmarks of Human Exploitation and Implications for Conservation Jayakody A. Sumith*,1,3, Kelly R. Munkittrick1 and N. Athukorale2 1Canadian Rivers Institute and Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, P.O. Box 5050, Saint John, New Brunswick, E2L 4L5, Canada 2Institute of Fundamental Studies, Hanthana Road, Kandy 20000, Sri Lanka 3Permanent Address: Office of the Registrar of Pesticides, Department of Agriculture, 1056, Getambe, P.O. Box 49, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka Abstract: Patterns of fish community composition in the Mahaweli ichthyological region of Sri Lanka were examined in agricultural tributaries of the Uma-oya catchment of the upper Mahaweli River in comparison to more pristine streams in a nature reserve in the Amban-ganga catchment. The Uma-oya catchment shows characteristics commonly observed in extensive agricultural exploitation such as impaired water quality and altered riparian vegetation. The most abundant fish species in the two regions were Garra ceylonensis, Devario malabaricus, and Rasbora daniconius, although their relative abundance differed between sites. G. ceylonensis and Neomacheilus notostigma were the only endemic fish species in common but the latter has been extremely depauperate. Endemism is higher in the reference sites (62.5%) than agricultural sites (ca. 25%); some of the reference streams showed greater diversity with unique fish species and a few species that have not been recorded previously in the catchment. The ichthyofaunal similarity between two catchments was 39% and fish species diversity was negatively correlated with stream gradients (Pearson correlation (-0.630); r2 = 39.6% p = 0.028). -

In Rajanganaya Reservoir, Sri Lanka

31 Sri Lanka J. Aquat. Sci. 19 (2014): 31-39 Food and feeding of Ehirava fluviatilis (Osteichthyes, Clupeidae) in Rajanganaya Reservoir, Sri Lanka INDIVARI D. MIHINDUKULASOORIYA and UPALI S. AMARASINGHE* Department of Zoology, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya GQ11600, Sri Lanka * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Ehirava fluviatilis is of marine origin and has colonized some freshwater reservoirs of Sri Lanka. A small scale fishery of E. fluviatilis exists at the outflow LB canal of Rajanganaya reservoir. This study was carried out to investigate food and feeding habits of E. fluviatilis collected from this location. Sampling was done fortnightly from the landings. From the length-weight relationship, an allometric growth is evident. The theoretical weight of 50 mm E. fluviatilis calculated from length weight relationship was 928 mg, a comparable value to that of the estuarine population in Bolgoda Lake, Sri Lanka but a higher value than that of reservoir population in Parakrama Samudra, Sri Lanka, indicating that the population in Rajanganaya is as healthy as estuarine population. The highest index of relative importance in the stomach contents was recorded for diatoms. In addition, two genera of copepods, two genera of cladocerans, and two genera of rotifer, one genus each of insect larvae and crustaceans other than copepods and cladocerans were also present. Diatoms were also an important food item. As colonization success of E. fluviatilis in inland reservoirs seems to be due to the presence of their preferred food, micro-crustaceans, findings of the present analysis will be useful for investigating physiological advantages of being a stenophagous fish species.