Communities of Color Protesting Vietnam, 1965-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982

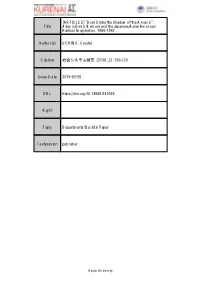

[ARTICLES] "Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb": Title Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 Author(s) UCHINO, Crystal Citation 社会システム研究 (2019), 22: 103-120 Issue Date 2019-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/241029 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb” 103 “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb”: Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 UCHINO Crystal Introduction This article explores the significance of the atomic bomb in the political imaginaries of Asian American activists who participated in the Asian American movement (AAM) in the 1960s and 1970s. Through an examination of articles printed in a variety of publications such as the Gidra, public speeches, and conference summaries, it looks at how the critical memory of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki acted as a unifying device of pan-Asian radical expression. In the global anti-colonial moment, Asian American activists identified themselves with the metaphorical monsters that had borne the violence of U.S. nuclear arms. In doing so, they expressed their commitment to a radical vision of social justice in solidarity with, and as a part of, the groundswell of domestic and international social movements at that time. This was in stark contrast to the image of the Asian American “model minority.” Against the view that antinuclear activism faded into apathy in the 1970s because other social issues such as the Vietnam War and black civil rights were given priority, this article echoes the work of scholars who have emphasized how nuclear issues were an important component of these rising movements. -

Wilkins-Fran.Pdf

Film as a Medium for Teaching the Supporting Characters of the Civil Rights Movement Frances M. Wilkins John Bartram High School Abstract The lesson plans included in this unit will provide three extension units for supplemental learning incorporating film to teach the civil rights movement. The premise is to expand the African American civil rights movement as envisioned in the curriculum to include the movements of other minority groups. The lessons are also designed to meet the unique learning needs of English language learners at the high school level. Strategies are given to adapt the material to a diverse high school classroom. Introduction In December 2009, “news that Asian students were being viciously beaten within the halls of South Philadelphia High stunned the city”. ¹ Many of the Asian students were my students. At the time of the riot, I was an English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) teacher at South Philadelphia High School and had dealt with the constant bullying and violence against the immigrant students for years. The incident resulted in an investigation by the Justice Department in which it was determined that the school district and the administrators at South Philadelphia High School had acted with ‘deliberate indifference’ to the systemic violence that targeted mostly Asian students.2 When the riot occurred, one of my Chinese students, Wei Chen, had learned in his U.S. History class that what was not legal in China was legal in the United States - organizing, protesting and that he had civil rights. The afternoon of the riot he made a phone call and reached out to various Asian American community organizations in Philadelphia for support. -

6 “THE BLACKS SHOULD NOT BE ADMINISTERING the PHILADELPHIA PLAN” Nixon, the Hard Hats, and “Voluntary” Affirmative Action

6 “THE BLACKS SHOULD NOT BE ADMINISTERING THE PHILADELPHIA PLAN” Nixon, the Hard Hats, and “Voluntary” Affirmative Action Trevor Griffey The conventional history of the rise of affirmative action in the late 1960s and early 1970s tends toward a too simple dialectic. The early creation and extension of affirmative action law is often described as an extension of the civil rights movement, whereas organized opposition to affirmative action is described as something that occurred later, as a backlash or reaction that did not fully take hold until Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980.1 In this chapter, I tell a different story. I describe the role that labor union resistance to affirmative action played in limiting the ability of the federal gov- ernment to enforce new civil rights laws well before the more overt backlash against affirmative action became ascendant in U.S. political culture in the 1980s and 1990s. There was no heyday for attempts by federal regulatory agencies to impose affirmative action on U.S. industry. There was no pristine origin against which a backlash could define itself, because enforcement of affirmative action had accommodated its opponents from the beginning. Affirmative action law emerged out of and in response to civil rights move- ment protests against the racism of federal construction contractors, whose discriminatory hiring policies were defended and often administered by the powerful building trades unions.2 But the resistance of those unions to the 1969 Revised Philadelphia Plan—the first government-imposed affirmative action plan—severely curtailed the ability of the federal government to enforce affirma- tive action in all industries. -

Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement: the Papers of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford)

Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement: The Papers of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford) Interviews, articles, speeches and FBI coverage bring a civil rights group into sharp focus • Date Range: 1962-1999 • Content: 17,210 pages • Source Library: Personal Collection of Dr. Muhammad Ahmad The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) formed in 1962 among undergraduates at Central State College. RAM engaged in voter registration drives, organized local economic boycotts and held free history classes at its North Philadelphia office. The group soon expanded its efforts, supporting demonstrations in the southern U.S. to end segregation and fighting to eliminate police brutality against the African-American community. RAM positioned itself as a revolutionary organization based around the tactics of using confrontational direct action to achieve its ends. The group upheld the right of African-Americans to use armed self-defense against racist violence. In 1967, RAM united street gangs into a youth organization called the Black Guards that battled racial oppression. Such groups as the Black Panther Party, the Republic of New Afrika and the African People’s Party superseded RAM. Muhammad Ahmad, a protégé of Malcolm X, was instrumental in RAM’s activities. In Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement, a wealth of material from Ahmad’s personal archive – letters, speeches, financial records and more – are augmented with FBI files and other primary sources. The collection sheds light on 1960s radicalism, politics and culture, and provides an ideal foundation for coursework in African-American studies, radical studies, post-Colonial studies and social history. Free trial Try this and other Archives Unbound collections free. -

I've Been Asked by Several People How the Current Level of Turmoil

I’ve been asked by several people how the current level of turmoil compares to 1968, which is the year several authorities describe as the historical low point for the republic. Also – for the record – 1965, 1967,1969 and 1970 should be considered in the comparison. In 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated, the United States deployed troops to Vietnam as combatants, not advisors, and the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles went up in smoke, literally, as a week-long race riot destroyed both life and property. You’ve heard the term “Burn, baby, burn,” it’s Watts that was burning – all beginning with a traffic stop. Newark New Jersey would burn in 1967, one of 159 race riots that swept cities in the United States during the "Long Hot Summer of 1967". Over the four days of rioting, looting, and property destruction, 26 people died and hundreds were injured. 1969 and 1970 were years of a different form of violent confrontation, centering on anti- Vietnam War acts of civil disobedience, including student strikes and the seizure of college campus buildings by the student mobs. In New York City, about 200 construction workers were mobilized by the New York State AFL-CIO to attack some 1,000 college and high school students and others who were protesting against the Vietnam War. This hard hat riot took place a few days after four students were shot and killed by Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State University. So, how does our present condition compare to the unrest of the 60s? No matter how badly delivered, the anti-war objective was clear: stop the war. -

Mountains That Take Wing – Angela Davis & Yuri Kochiyama: a Conversation on Life, Struggles & Liberation (97 Minutes, 2009)

MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING – ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA: A CONVERSATION ON LIFE, STRUGGLES & LIBERATION (97 MINUTES, 2009) Thirteen years, two inspiring women, both radical activists — one conversation. "Telling the story of twentieth-century social change as a chronicle of affection, of correspondence in postcards and letters, of mutual admiration and activist friendship, of two embraces between two comrades, Mountains That Take Wing reminds us that the wild wonder of liberation struggle is not only ours for the taking but already, literally, in our own hands. It is a film that educates with tenderness and passion." — ERICA R. EDWARDS, PROFESSOR (UC RIVERSIDE) January 2008. LEFT: Angela Y. Davis & Yuri Kochiyama at Kochiyama’s apartment in Oakland, California. RIGHT: H. L. T. Quan, Angela Y. Davis, Yuri Kochiyama, S. K. Thrift & C. A. Griffith in Davis’ home in Oakland, California. PHOTOS © QUAD PRODUCTIONS MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING – ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA features conversations that span thirteen years between two formidable women whose lives and political work remain at the epicenter of the most important civil rights struggles in the U.S. Through conversations that are intimate and profound, we learn about Davis, an internationally renowned scholar-activist and 89-year-old Kochiyama, a revered grassroots community activist and 2005 Nobel Peace Prize nominee. They share experiences as political prisoners as well as a profound passion for justice. On subjects ranging from the vital but often sidelined role of women in 20th century social movements and community empowerment, to the prison industrial complex, war and the cultural arts, Davis's and Kochiyama's comments offer critical lessons for understanding our nation's most important social movements while providing tremendous hope for its youth and the future. -

Hard Hat Riots of 1970'S

Hard Hat Riots of 1970’s Written by Chris L. Joanet, Retired Union Carpenter, Women & Human Rights Activist since 1970 Written November 10, 2012 by Chris L. Joanet, Forty-three (43) year carpenter and female activist. The late 1960’s and early 1970’s was a period of social growth and change, a time when American citizens searched for their own identity. The “Hard Hat Riot” of May, 1970, clearly showed the new divisions that had emerged in American culture. The middle class labor force, dubbed the “blue-collared” workers, were in opposition to so many of their fathers and sons going to war in Vietnam, while many college students were excluded from the draft. This brought about obvious tensions between the two groups, which were embodied in a riot of construction workers and their confrontation with protestors on the steps of Wall Street in New York City. The “Hard Hat Riot” not only left multiple people injured and arrested, but provided proof of the ever-growing divisions within America. On May 9, 1970, construction workers from all over New York City converged on a peaceful antiwar demonstration taking place on Wall Street. The workers, still wearing their construction helmets, attacked the group of protestors, leaving nearly 70 people in need of medical attention. The mob reached Wall Street at about noon, where students had been calling for the withdrawal of military presence from Cambodia and Vietnam, among other things… In my opinion this was the start of the hatred by 99.99% white middle class male and construction workers of America for people other than what they perceived as American Patriots and the Republicans pandered to this intellect to win most of the Presidencies in the United States for the next thirty years. -

Cathedral Catholic High School Course Catalog

Cathedral Catholic High School Course Catalog Course Title: History of Vietnam War Course #: 1638 Course Description: This semester long course will cover French and American involvement in Vietnam during the second half of the 20th century. From colonization to independence, students will examine America’s intervention in Vietnam from various perspectives including the French, American, Communist Vietnamese fighters, Vietnamese people and the Communist superpowers supplying North Vietnam. The course will include a look at the geography, society, economy and history of Vietnam. UC/CSU Approval: “g” approved Grade Level: 11-12 Estimated Homework Per Week: None Prerequisite: None Recommended Prerequisite Skills: ● Analytical Writing Skills - CDW style paragraph writing ● Map reading skills ● Note-taking skills Text: “Vietnam: A History” by Stanley Karnow https://www.amazon.com/Vietnam-History-Stanley-Karnow/dp/0140265473 Course Grade Scale: ● 35% Homework/Classwork ● 30% Projects ● 25% Tests/Quizzes ● 10% Presentations Units: I. US and Communism: Introduction to Communism and the Cold War Unit 1 focuses on Ho Chi Minh’s personal conflict between the ideologies of capitalism and nationalism, the influence of China and the Soviet Union in aiding North Vietnam’s military expansion and spread of Communist ideology and the role the Cold War played in causing America to fear ‘losing Vietnam’ to Communism as Truman had lost China, preventing Kennedy and Johnson from disengaging from wars they otherwise may have avoided. Assessments Chart: American Anti-communist policies of the 50’s & 60’s Selected Readings from Karnow - Chapter 1: The War Nobody Won ● Annotate and answer critical thinking questions ● Class Discussion. Critical Thinking: Karnow's objectivity, goals in charting a course for the book, statements made about Vietnam's place in the Cold War. -

Snazzlefrag's History of the Vietnam War DSST Study Notes

Snazzlefrag’s History of the Vietnam War DSST Study Notes Contact: http://www.degreeforum.net/members/snazzlefrag.html Hosted at: http://www.free-clep-prep.com Han/Tang Dynasty ruled Vietnam for 1000 years. Buddhism 939 Independence from China (1279 Repelled/1407 Invaded(Ming)/1428 Free) 1620 Vietnam divided b/n Trinh (North-Hanoi) Nguyen (South-Hue[fertile Mekong]). 1858 French invade. 1862 (treaty) Protectorate of CochinChina (Capital: Saigon, SV). 1887 Vietnam (Tonkin/Annam)/Cambodia=French Indochina. Catholicism. 1893 Laos added into Indochina. 1919 France ignores Ho Chi Minh’s demands at Versailles Peace Conference. Rep in Fr Parliament. Free speech. Political Prisoners. 1926 Bao Dai becomes last Vietnamese Emperor (supported by French). 1927 Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDD). Vietnam Quoc Dan Dang. "Nguyen Thai Hoc" 1930 Ho founds Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) 1940 Japan occupies Vietnam (keeps Fr. bureaucracy in place to run Fr. Indochina). 1941 Ho Chi Minh founds Viet Minh League for Viet Indep. (Comm/soc/nats). 1941 King Sihanouk of Cambodia given throne by French. Overthrown in 1970 coup. 1945 Japs take complete control but Viet Minh takes Hanoi in August Revolution (not a rev). China moves into NV (as planned by allies). Set up adminstration down to 16th Parallel. Sept 2, Emperor Bao Dai abdicates in favour of Ho Chi Minh. Japan surrenders WWII Ho takes power (president), establishes Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) Truman rejects DRV’s request for formal recognition. 1945 Sept 26: OSS Lt Col Peter Dewey (repating US POWs) shot. 1st US Casualty in Vietnam. 1945 Oct: British/Indian troops move in to SV. -

Downloaded At

CROSSCURRENTS 2004-2005 Vol. 28, No. 1 (2004-2005) CrossCurrents Newsmagazine of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center Center Honors Community Leaders and Celebrates New Department at 36th Anniversary Dinner MARCH 5, 2005—At its 36th anniversary dinner, held in Covel Commons at UCLA, the Center honored commu- nity leaders and activists for their pursuit of peace and justice. Over 400 Center supporters attended the event, which was emceed by MIKE ENG, mayor of Monterey Park and UCLA School of Law alumnus. PATRICK AND LILY OKURA of Bethesda, Maryland, who both recently passed away, sponsored the event. The Okuras established the Patrick and Lily Okura En- dowment for Asian American Mental Health Research at UCLA and were long involved with the Center and other organizations, including the Japanese American Citizens League and the Asian American Psychologists Association. Honorees included: SOUTH ASIAN NETWORK, a community-based nonprofit or- ganization dedicated to promoting health and empow- erment of South Asians in Southern California. PRosY ABARQUEZ-DELACRUZ, a community activist and vol- unteer, and ENRIQUE DELA CRUZ, a professor of Asian American Studies at California State University, Northridge, The late Patrick and Lily Okura. and UCLA alumnus. SUELLEN CHENG, curator at El Pueblo de Los Angeles standing Book Award. Historical Monument, executive director of the Chinese UCLA Law Professor JERRY KANG, a member of the Center’s American Museum, and UCLA alumna, and MUNSON A. Faculty Advisory Committee, delivered a stirring keynote WOK K , an active volunteer leader in Southern California address. TRITIA TOYOTA, former broadcast journalist and for more than thirty years. -

The President's Conservatives: Richard Nixon and the American Conservative Movement

ALL THE PRESIDENT'S CONSERVATIVES: RICHARD NIXON AND THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE MOVEMENT. David Sarias Rodriguez Department of History University of Sheffield Submitted for the degree of PhD October 2010 ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation exammes the relationship between the American conservative movement and Richard Nixon between the late 1940s and the Watergate scandal, with a particular emphasis on the latter's presidency. It complements the sizeable bodies ofliterature about both Nixon himself and American conservatism, shedding new light on the former's role in the collapse of the post-1945 liberal consensus. This thesis emphasises the part played by Nixon in the slow march of American conservatism from the political margins in the immediate post-war years to the centre of national politics by the late 1960s. The American conservative movement is treated as a diverse epistemic community made up of six distinct sub-groupings - National Review conservatives, Southern conservatives, classical liberals, neoconservatives, American Enterprise Institute conservatives and the 'Young Turks' of the New Right - which, although philosophically and behaviourally autonomous, remained intimately associated under the overall leadership of the intellectuals who operated from the National Review. Although for nearly three decades Richard Nixon and American conservatives endured each other in a mutually frustrating and yet seemingly unbreakable relationship, Nixon never became a fully-fledged member of the movement. Yet, from the days of Alger Hiss to those of the' Silent Majority', he remained the political actor best able to articulate and manipulate the conservative canon into a populist, electorally successful message. During his presidency, the administration's behaviour played a crucial role - even if not always deliberately - in the momentous transformation of the conservative movement into a more diverse, better-organised, modernised and more efficient political force. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian American and African American Masculinities: Race, Citizenship, and Culture in Post -Civil Rights A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Phil osophy in Literature by Chong Chon-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Lowe, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Judith Halberstam Professor Nayan Shah Professor Shelley Streeby Professor Lisa Yoneyama This dissertation of Chong Chon-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION I have had the extraordinary privilege and opportunity to learn from brilliant and committed scholars at UCSD. This dissertation would not have been successful if not for their intellectual rigor, wisdom, and generosity. This dissertation was just a dim thought until Judith Halberstam powered it with her unique and indelible iridescence. Nayan Shah and Shelley Streeby have shown me the best kind of work American Studies has to offer. Their formidable ideas have helped shape these pages. Tak Fujitani and Lisa Yoneyama have always offered me their time and office hospitality whenever I needed critical feedback.