Wilkins-Fran.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982

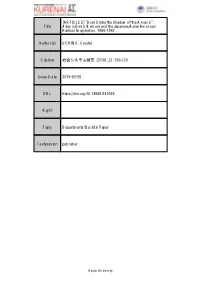

[ARTICLES] "Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb": Title Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 Author(s) UCHINO, Crystal Citation 社会システム研究 (2019), 22: 103-120 Issue Date 2019-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/241029 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb” 103 “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb”: Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 UCHINO Crystal Introduction This article explores the significance of the atomic bomb in the political imaginaries of Asian American activists who participated in the Asian American movement (AAM) in the 1960s and 1970s. Through an examination of articles printed in a variety of publications such as the Gidra, public speeches, and conference summaries, it looks at how the critical memory of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki acted as a unifying device of pan-Asian radical expression. In the global anti-colonial moment, Asian American activists identified themselves with the metaphorical monsters that had borne the violence of U.S. nuclear arms. In doing so, they expressed their commitment to a radical vision of social justice in solidarity with, and as a part of, the groundswell of domestic and international social movements at that time. This was in stark contrast to the image of the Asian American “model minority.” Against the view that antinuclear activism faded into apathy in the 1970s because other social issues such as the Vietnam War and black civil rights were given priority, this article echoes the work of scholars who have emphasized how nuclear issues were an important component of these rising movements. -

Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement: the Papers of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford)

Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement: The Papers of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford) Interviews, articles, speeches and FBI coverage bring a civil rights group into sharp focus • Date Range: 1962-1999 • Content: 17,210 pages • Source Library: Personal Collection of Dr. Muhammad Ahmad The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) formed in 1962 among undergraduates at Central State College. RAM engaged in voter registration drives, organized local economic boycotts and held free history classes at its North Philadelphia office. The group soon expanded its efforts, supporting demonstrations in the southern U.S. to end segregation and fighting to eliminate police brutality against the African-American community. RAM positioned itself as a revolutionary organization based around the tactics of using confrontational direct action to achieve its ends. The group upheld the right of African-Americans to use armed self-defense against racist violence. In 1967, RAM united street gangs into a youth organization called the Black Guards that battled racial oppression. Such groups as the Black Panther Party, the Republic of New Afrika and the African People’s Party superseded RAM. Muhammad Ahmad, a protégé of Malcolm X, was instrumental in RAM’s activities. In Black Nationalism and the Revolutionary Action Movement, a wealth of material from Ahmad’s personal archive – letters, speeches, financial records and more – are augmented with FBI files and other primary sources. The collection sheds light on 1960s radicalism, politics and culture, and provides an ideal foundation for coursework in African-American studies, radical studies, post-Colonial studies and social history. Free trial Try this and other Archives Unbound collections free. -

Mountains That Take Wing – Angela Davis & Yuri Kochiyama: a Conversation on Life, Struggles & Liberation (97 Minutes, 2009)

MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING – ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA: A CONVERSATION ON LIFE, STRUGGLES & LIBERATION (97 MINUTES, 2009) Thirteen years, two inspiring women, both radical activists — one conversation. "Telling the story of twentieth-century social change as a chronicle of affection, of correspondence in postcards and letters, of mutual admiration and activist friendship, of two embraces between two comrades, Mountains That Take Wing reminds us that the wild wonder of liberation struggle is not only ours for the taking but already, literally, in our own hands. It is a film that educates with tenderness and passion." — ERICA R. EDWARDS, PROFESSOR (UC RIVERSIDE) January 2008. LEFT: Angela Y. Davis & Yuri Kochiyama at Kochiyama’s apartment in Oakland, California. RIGHT: H. L. T. Quan, Angela Y. Davis, Yuri Kochiyama, S. K. Thrift & C. A. Griffith in Davis’ home in Oakland, California. PHOTOS © QUAD PRODUCTIONS MOUNTAINS THAT TAKE WING – ANGELA DAVIS & YURI KOCHIYAMA features conversations that span thirteen years between two formidable women whose lives and political work remain at the epicenter of the most important civil rights struggles in the U.S. Through conversations that are intimate and profound, we learn about Davis, an internationally renowned scholar-activist and 89-year-old Kochiyama, a revered grassroots community activist and 2005 Nobel Peace Prize nominee. They share experiences as political prisoners as well as a profound passion for justice. On subjects ranging from the vital but often sidelined role of women in 20th century social movements and community empowerment, to the prison industrial complex, war and the cultural arts, Davis's and Kochiyama's comments offer critical lessons for understanding our nation's most important social movements while providing tremendous hope for its youth and the future. -

Downloaded At

CROSSCURRENTS 2004-2005 Vol. 28, No. 1 (2004-2005) CrossCurrents Newsmagazine of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center Center Honors Community Leaders and Celebrates New Department at 36th Anniversary Dinner MARCH 5, 2005—At its 36th anniversary dinner, held in Covel Commons at UCLA, the Center honored commu- nity leaders and activists for their pursuit of peace and justice. Over 400 Center supporters attended the event, which was emceed by MIKE ENG, mayor of Monterey Park and UCLA School of Law alumnus. PATRICK AND LILY OKURA of Bethesda, Maryland, who both recently passed away, sponsored the event. The Okuras established the Patrick and Lily Okura En- dowment for Asian American Mental Health Research at UCLA and were long involved with the Center and other organizations, including the Japanese American Citizens League and the Asian American Psychologists Association. Honorees included: SOUTH ASIAN NETWORK, a community-based nonprofit or- ganization dedicated to promoting health and empow- erment of South Asians in Southern California. PRosY ABARQUEZ-DELACRUZ, a community activist and vol- unteer, and ENRIQUE DELA CRUZ, a professor of Asian American Studies at California State University, Northridge, The late Patrick and Lily Okura. and UCLA alumnus. SUELLEN CHENG, curator at El Pueblo de Los Angeles standing Book Award. Historical Monument, executive director of the Chinese UCLA Law Professor JERRY KANG, a member of the Center’s American Museum, and UCLA alumna, and MUNSON A. Faculty Advisory Committee, delivered a stirring keynote WOK K , an active volunteer leader in Southern California address. TRITIA TOYOTA, former broadcast journalist and for more than thirty years. -

Communities of Color Protesting Vietnam, 1965-1975

LESSON PLANS GLOBAL ISSUES: FREEDOM AT HOME, FREEDOM ABROAD: Communities of Color Protesting Vietnam, 1965-1975 Image Caption (Detail) [ Link ] OVERVIEW COMMON CORE STATE Students will learn about the anti-Vietnam war movement and its STANDARDS intersections with the black freedom struggle and the Asian American CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.5.2 movement by investigating primary sources to uncover these diverse Determine two or more main ideas of a text perspectives. and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. STUDENT GOALS (Grade 5) Students will be able to contextualize the Vietnam War as a long war for the Vietnamese, situating it within an extended struggle for CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.4 independence and national autonomy. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including Students will learn about how the Vietnam War helped to catalyze vocabulary specific to domains related to Asian American identity formation. They will examine the role of key history/social studies. activists like Yuri Kochiyama, exploring her political perspective in a (Grades 6-8) number of movements. They will also learn about the experiences of Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian refugees who resettled in CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.6 cities like New York after being displaced by the Vietnam War. Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by Students will make connections between the American antiwar assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, movement and the black freedom struggle by understanding the and evidence. uneven effects of conscription, which disproportionately drafted (Grades 11-12) African American men during the Vietnam War. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian American and African American Masculinities: Race, Citizenship, and Culture in Post -Civil Rights A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Phil osophy in Literature by Chong Chon-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Lowe, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Judith Halberstam Professor Nayan Shah Professor Shelley Streeby Professor Lisa Yoneyama This dissertation of Chong Chon-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION I have had the extraordinary privilege and opportunity to learn from brilliant and committed scholars at UCSD. This dissertation would not have been successful if not for their intellectual rigor, wisdom, and generosity. This dissertation was just a dim thought until Judith Halberstam powered it with her unique and indelible iridescence. Nayan Shah and Shelley Streeby have shown me the best kind of work American Studies has to offer. Their formidable ideas have helped shape these pages. Tak Fujitani and Lisa Yoneyama have always offered me their time and office hospitality whenever I needed critical feedback. -

December 21, 2020 California Department of Education 1430 N

December 21, 2020 California Department of Education 1430 N Street Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear Governor Newsom, Superintendent Thurmond, Dr. Darling-Hammond, and Instructional Quality Commission Members, We are writing on behalf of our organizations with deep concern about California’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (ESMC). Based on the problematic “Guiding Values and Principles,” the ESMC promotes and romanticizes specific political ideologies with no counterbalancing perspective. Guidelines should be added, and the sample lessons revised, to ensure that ethnic studies courses focus on a thorough understanding about ethnic groups, social issues, and civic engagement, without political proselytizing. As organizations who represent many of the ethnic groups mentioned in the ESMC and who work to educate Americans about the truthful depiction of history, we call on you to ensure there is an accurate portrayal of the perils many American immigrants have overcome as a result of communism. Tens of millions of Americans trace their heritage to current or former communist countries. This past decade has demonstrated that communism still poses a threat to the human rights of the one-fifth of the world’s population who live under communist regimes. It is vital our educational systems teach the truth about communism to all students. Many victims of former communist countries – Cambodia, Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and beyond – sought asylum in the United States as a result of the persecution they faced under oppressive communist dictators in their home countries and many victims of current communist countries – from Cuba, China, North Korea, and Venezuela to name a few – take great lengths to come to the United Stated to find refuge today. -

RESISTANCE 101 a Lesson for Inauguration Teach-Ins and Beyond

RESISTANCE 101 A Lesson for Inauguration Teach-Ins and Beyond This lesson has been prepared by Teaching for Change staff for teachers to use for Inauguration Teach-Ins and beyond. It is an introductory lesson for students, allowing them to “meet” people from throughout U.S. history who have resisted injustice and to learn from the range of strategies they have used. It is important to note, and to point out to students, that this list represents just a small sample of the people, time periods, struggles, and strategies we could have included. It is our hope that students not only choose to learn more about the people featured in this lesson, but that they research and create more bios. In fact, students could create a similar lesson with specific themes activists in their community, youth activists, environmental activists, and many more. The lesson is based on the format of a Rethinking Schools lesson called Unsung Heroes and draws from lessons by Teaching for Change on women’s history and the Civil Rights Movement, including Selma. This lesson can make participants aware of how many more activists there are than just the few heroes highlighted in textbooks, children’s books, and the media. However the lesson provides only a brief introduction to the lives of the people profiled. In order to facilitate learning more, we limited our list to people whose work has been well enough documented that students can find more in books and/or online. Materials and Preparation Handout No. 1: Biographies – Print the handout and cut the paper into individual strips, with each strip displaying one biography. -

Resources for Combating Racism

Resources for Combating Racism Readings Videos Podcasts and Other Resources Books Black Lives Matter and Asian 13 Brilliant TED Talks on Pacific Decolonization (YouTube) Racism, Colorism and Color, Race, and English Prejudice (Odyssey) Language Teaching: Shades Far East Deep South (New Day of Meaning (Andy Curtis and Films) 13 Podcasts that Can Help Us Mary Romney, Editors) Learn About Race and Full Interview: Daniel Dae Kim On Racism in America Racial Reconstruction: Black Anti-Asian Violence In The US | (PureWow) Inclusion, Chinese Exclusion, TODAY (YouTube) and the Fictions of Citizenship Black & Asian Solidarity with (Edlie L. Wong) How Coronavirus Racism Infected Alicia Garza and Shaw San My High School | NYT Opinion Liu (Black Diplomats) Transpacific Antiracism: (YouTube) Afro-Asian Solidarity in 20th- Blood on Gold Mountain Century Black America, Jim and Jap Crow: A Cultural (Huang & Huang) Japan, and Okinawa History of 1940s Interracial (Yuichiro Onishi) America (C-SPAN) A Conversation About Asian and Black Racism (Asian Blogs Leading Asian-American Voices Americans Advancing Justice Address Anti-Asian Racism • LA) A List of Books About BRAVE NEW FILMS (YouTube) Racism, Films, and Other Anti The History Of Anti-Asian Racism Resources (The Write Mountains That Take Wing: Sentiment In The U.S (NPR) of Your Life) Angela Davis & Yuri Kochiyama (Full Documentary) Let’s Talk! Supporting Asian Academic Articles (FilmsForAction.org) and Asian American Students Through COVID-19 Webinar Guerrettaz, A. M., & Zahler, OCA SUMMIT: Stop Repeating Series (MGH Institute of T. (2017). Black lives matter History: Asian Pacific Americans Health Professions) in TESOL: De‐silencing race at the Dawn of a New Civil Rights ● Webinar #1: Anti-Asian in a second language Era (YouTube) Racism During the academic literacy course. -

THE 28 PERCENT Women Make up Only 28% of the STEM Workforce

VOLUME IX // SEPTEMBER 2021 welcome back! THE 28 PERCENT Women make up only 28% of the STEM workforce. This newsletter aims to change that. By Jaidyn, 10th grade By Jaidyn, 01 - FRONT COVER & ART 04 - A COOL WOMAN 02 - EVENTS CALENDAR 05 - WRITTEN BY YOU 03 - PROGRAMS & 06 - CREDITS & CONTACT SCHOLARSHIPS 02 // EVENTS CALENDAR wednesday september 15 @ 11:00 - 12:00pm Black Women in STEM Imagine Tomorrow 15 Despite record numbers of Black women earning higher education degrees in STEM, only 5% of managerial jobs in STEM are held by Black women and men combined. We can't expect women of color to remain in work environments where they can't grow and thrive. Join us for a discussion on how women of sign up! color in STEM are overcoming sexism and racism to hold important titles and positions, making groundbreaking discoveries, and pushing the boundaries of who is included in the next generation of STEM innovators. friday september 17 @ 1:00 - 3:30pm Girl Up STEM for Social Good Bootcamp: 17 Health and Technology Are you excited about the ways technology is creating positive change for people's health and wellbeing globally? Are you intrigued by X-rays that automatically detect bone fractures, drone delivered medical supplies to rural areas, or wearable devices that allow sign up! you to track your sleep, heart rate, and step count? Join this bootcamp to learn more about the intersections between technology and health, with the opportunity to design your own tech-based solution for a health issue in your community! friday september 24 @ 6:00 - 9:00pm Madame Gandhi & More at Grand Performances Join GRAND PERFORMANCES on Friday September 24th for a team up with KCRW's 27 Summer Nights for a special night featuring indie electronic singer, percussionist and activist, Madame Gandhi. -

Crosscurrents Vol. 36, 2014

VOLUME 36 Currents 2014 Annual Newsmagazine of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center CENTER REMEMBERS THE LEGACY OF YURI KOCHIYAMA Yuri Kochiyama, a long-time activist and champion for hu- Kochiyama, Ryan Kochiyama, Kai Williams, Karen Tei Ya- man rights, passed away on June 1, 2014 at the age of 93. She mashita, Thandisizwe Chimurenga, Renee Tajima-Peña, and is well-known for her work towards reparations for Japanese Diane Fujino. On the Amerasia blog, Kao also wrote about the Americans after their World War II incarceration, her connec- touching memorials held in Kochiyama’s honor that took place tions with Malcom X and the Black Liberation Movement, and this year in Oakland, Los Angeles, and New York. her activism to free political prisoners and around other social As Kao stated, “Yuri’s spirit of boundless generosity and justice issues. fearless acts of revolutionary kindness shine light onto a better The Center is honored to have worked with Kochiyama. world.” The Center is grateful to have experienced Kochiya- Her time at UCLA as an “activist-in-residence” and a Visit- ma’s light and to be a part of preserving her legacy of revolu- ing Scholar in 1998, through the UCLA Alumni and Friends tionary struggle and activism for future generations. of Japanese Ancestry Chair in Japanese American Studies Fund, enriched the life of the Center and the campus. The Center had the amazing opportunity of working with her on the award-winning memoir Passing It On (UCLA Asian Ameri- can Studies Center Press, 2004) and housing the Yuri Kochi- yama Collection, with papers, photographs, flyers and memo- rabilia relating to the Asian American Movement and her own personal life. -

Appendix A: Alphabetical List of All Name Suggestions

Appendix A: Alphabetical List of all Name Suggestions 1. Angela Angela Davis was a revolutionary leader in and ally of the Black Panther Party and Black Davis Power movement of the 1960s and 70s. Her resounding activism challenged the authority of the oppressive Nixon administration and the segregationist sentiments that lingered in the country after the signing of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, and she worked hard to improve her own East Bay community (including Berkeley). Despite the prevalence of names of African-American leaders in BUSD schools, Davis’ Communist affiliations give her a unique place in history (and one that has won her a great deal of scrutiny). Davis spent many years as a professor at UC Santa Cruz, and has repeatedly stated that education is the key to social change, so she would be an excellent role model for students and educators alike. 2. Audre Audre Lorde was an American writer,feminist, librarian, and civil rights activist. She was a Lorde self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” who dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, and homophobia. As a poet, her work largely dealt with issues related to civil rights, feminism, lesbianism, illness and disability, and the exploration of black female identity. 3. Barack Reasons we chose Barack Obama: 1. He was our president. He was the best president, says Obama Ari & Vivi. 2. He did really good things for our country. He helped keep people safe and made sure people were following the laws.