Dead Loss: the High Cost of Poor Farming Practices and Mortalities on Salmon Farms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Some Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Skip Spawning?

SCRS/2006/088 Col. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 60(4): 1141-1153 (2007) DO SOME ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA SKIP SPAWNING? David H. Secor1 SUMMARY During the spawning season for Atlantic bluefin tuna, some adults occur outside known spawning centers, suggesting either unknown spawning regions, or fundamental errors in our current understanding of bluefin tuna reproductive schedules. Based upon recent scientific perspectives, skipped spawning (delayed maturation and non-annual spawning) is possibly prevalent in moderately long-lived marine species like bluefin tuna. In principle, skipped spawning represents a trade-off between current and future reproduction. By foregoing reproduction, an individual can incur survival and growth benefits that accrue in deferred reproduction. Across a range of species, skipped reproduction was positively correlated with longevity, but for non-sturgeon species, adults spawned at intervals at least once every two years. A range of types of skipped spawning (constant, younger, older, event skipping; and delays in first maturation) was modeled for the western Atlantic bluefin tuna population to test for their effects on the egg-production-per-recruit biological reference point (stipulated at 20% and 40%). With the exception of extreme delays in maturation, skipped spawning had relatively small effect in depressing fishing mortality (F) threshold values. This was particularly true in comparison to scenarios of a juvenile fishery (ages 4-7), which substantially depressed threshold F values. Indeed, recent F estimates for 1990-2002 western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock assessments were in excess of threshold F values when juvenile size classes were exploited. If western bluefin tuna are currently maturing at an older age than is currently assessed (i.e., 10 v. -

A Preliminary Study on the Stomach Content of Southern Bluefin Tuna Thunnus Maccoyii Caught by Taiwanese Longliner in the Central Indian Ocean

CCSBT-ESC/0509/35 A preliminary study on the stomach content of southern bluefin tuna Thunnus maccoyii caught by Taiwanese longliner in the central Indian Ocean Kwang-Ming Liu1, Wei-Ke Chen2, Shoou-Jeng Joung2, and Sui-Kai Chang3 1. Institute of Marine Resource Management, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan. 2. Department of Environmental Biology and Fisheries Science, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan. 3. Fisheries Agency, Council of Agriculture, Taipei, Taiwan. Abstract The stomach contents of 63 southern bluefin tuna captured by Taiwanese longliners in central Indian Ocean in August 2004 were examined. The size of tunas ranged from 84-187 cm FL (12-115 kg GG). The length and weight frequency distributions indicated that most specimens were in the range of 100-130 cm FL with a body weight between 10 and 30 kg for both sexes. The sexes- combined relationship between dressed weight and fork length can be described by W = 6.975× 10-6× FL3.1765 (n=56, r2=0.967, p < 0.05). The subjective index of fullness of specimens was estimated as: 1 = empty (38.6%), 2 = <half full (47.37%), 3 = half full (3.51%), 4 = >half full (5.26%), and 5 = full (5.26%). For the stomachs with prey items, almost all the preys are pisces and the proportion of each prey groups are fishes (95.6%), cephalopods (2.05%), and crustaceans (0.02%). In total, 6 prey taxa were identified – 4 species of fish, 1 unidentified pisces, 1 unidentified crustacean, and 1 unidentified squid. The 4 fish species fall in the family of Carangidae, Clupeidae, Emmelichthyidae, and Hemiramphidae. -

Monitoring Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon and Commercial Finfish Habitat Use in the New York Lease Area

OCS Study BOEM 2019-074 Monitoring Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon and Commercial Finfish Habitat Use in the New York Lease Area US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs OCS Study BOEM 2019-074 Monitoring Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon and Commercial Finfish Habitat Use in the New York Lease Area June 2019 Authors: Michael G. Frisk, Professor School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794. Evan C. Ingram, Graduate Student School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794. Keith Dunton, Assistant Professor Department of Biology, Monmouth University, 400 Cedar Avenue, West Long Branch, New Jersey 07764. Prepared under Cooperative Agreement M16AC00003 US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs DISCLAIMER Study collaboration and funding were provided by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, under Agreement Number M16AC00003. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This project was funded by both BOEM and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC). REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Data and Information Systems webpage (http://www.boem.gov/Environmental-Studies- EnvData/), click on the link for the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS), and search on 2019-074. -

Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-53 Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units June 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of the Na tional Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible due to time constraints. Documents published in this series may be referenced in the scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-NWFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest & Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has since been split into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series is now being used by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. This document should be cited as follows: Waknitz, F.W., T.J. Tynan, C.E. Nash, R.N. Iwamoto, and L.G. Rutter. 2002. Review of potential impacts of Atlantic salmon culture on Puget Sound chinook salmon and Hood Canal summer-run chum salmon evolutionarily significant units. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-NWFSC-53, 83 p. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-53 Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units F. -

Overview of the Impacts of Introduced Salmonids on Australian Native Fauna

OVERVIEW OF THE IMPACTS OF INTRODUCED SALMONIDS ON AUSTRALIAN NATIVE FAUNA by P. L. Cadwallader prepared for the Australian Nature Conservation Agency 1996 ~~ AUSTRALIA,,) Overview of the Impacts of Introduced Salmonids on Australian Native Fauna by P L Cadwallader The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commonwealth Government, the Minister for the Environment or the Director of National Parks and Wildlife. ISBN 0 642 21380 1 Published May 1996 © Copyright The Director of National Parks and Wildlife Australian Nature Conservation Agency GPO Box 636 Canberra ACT 2601 Design and art production by BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra Cover illustration by Karina Hansen McInnes CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 SUMMARY 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. SPECIES OF SALMONIDAE IN AUSTRALIA 7 2.1 Brown trout 7 2.2 Rainbow trout 8 2.3 Brook trout 9 2.4 Atlantic salmon 9 2.5 Chinook salmon 10 2.6 Summary of present status of salmonids in Australia 11 3. REVIEW OF STUDIES ON THE IMPACTS OF SALMONIDS 13 3.1 Studies on or relating to distributions of salmonids and native fish 13 Grey (1929) Whitley (1935) Williams (1964) Fish (1966) Frankenberg (1966, 1969) Renowden (1968) Andrews (1976) Knott et at. (1976) Cadwallader (1979) Jackson and Williams (1980) Jackson and Davies (1983) Koehn (1986) Jones et al. (1990) Lintermans and Rutzou (1990) Minns (1990) Sanger and F ulton (1991) Sloane and French (1991) Shirley (1991) Townsend and Growl (1991) Hamr (1992) Ault and White (1994) McIntosh et al. (1994) Other Observations and Comments 3.2 Studies Undertaken During the Invasion of New Areas by Salmonids 21 Tilzey (1976) Raadik (1993) Gloss and Lake (in prep) 3.3 Experimental Introduction study 23 Fletcher (1978) 3.4 Feeding Studies, Including Analysis of Dietary Overlap and Competition, and Predation 25 Introductory Comments Morrissy (1967) Cadwallader (1975) Jackson (1978) Cadwallader and Eden (1981,_ 1982) Sagar and Eldon (1983) Glova (1990) Glova and Sagar (1991) Kusabs and Swales (1991) Crowl et at. -

Atlantic Salmon Critical Habitat

Endangered Species Act and FERC Hydroelectric Projects Jeff Murphy & Julie Crocker NHA New England Meeting November 16, 2010 Shortnose Sturgeon • Federally listed as endangered in 1967 • Listed under the sole jurisdiction of NOAA Fisheries • 19 Populations occur along the East Coast Shortnose sturgeon in New England… • Maine – Penobscot River, Kennebec/Sheepscot/Androscoggin complex, Saco River • Massachusetts – Merrimack River, Connecticut River Shortnose Sturgeon & Hydroelectric Projects Challenges Shortnose sturgeon typically spawn near the fall line – often at the base of a dam where operations can affect the suitability of spawning habitat, affect the movements of adults or viability of eggs and larvae Upstream Passage – Sturgeon don’t negotiate ladders well and have limited success entering fish lifts Downstream Passage – Shortnose sturgeon make downstream movements as yearlings and adults (large variability in size) and can be vulnerable to impingement at relatively low velocities Stranding - vulnerable to low dissolved oxygen and high temperatures that can occur in isolated pools Atlantic Sturgeon Proposed Listing Rule published October 6, 2010 Public comment period open until January 4, 2011 NOAA Fisheries has 1 year to publish a final rule There is no prohibition on “take” of proposed species, but the conference provisions of the ESA apply Atlantic Sturgeon Proposed Listing Proposal to list 5 Distinct Population Segments – Gulf of Maine (threatened); New York Bight (endangered); Chesapeake Bay (endangered); Carolina (endangered); and, South Atlantic (endangered) Gulf of Maine DPS of Atlantic Salmon Atlantic salmon in the Gulf of Maine (GOM) Distinct Population Segment (DPS) is jointly listed by NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. -

Overview of Aquaculture in the United States

Overview of Aquaculture in the United States Centers for Epidemiology & Animal Health USDA:APHIS:VS 2150 Centre Ave., Bldg. B, MS 2E7 Fort Collins, Colroado 80526-8117 (970) 494-7000 [email protected] October 1995 Aquaculture in the United States is a diverse industry which includes production of a variety of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and plants. Total estimated U.S. aquaculture production in 1992 was 313,518 metric tons with production income totaling $724 million (1). Thus, in terms of economic importance, the aquaculture industry is comparable in value to the sheep industry and equivalent to either 18 percent of the swine industry or 30 percent of the turkey industry. Also, an infrastructure of producers, processors, wholesalers, and retailers exists that is similar to that found in traditional livestock. A system of providers exists, which numbered over 2,000 in 1994, that supplies feeds, vaccines, fish diagnostics, medications, growth hormones, and physical equipment (pumps, feeders, processing machines) (2). The objective of this report is to investigate diversity within the industry by providing an overview of the types of aquatic animals being cultured in the U.S., trends in the size and geographic distribution of specific components of the industry, existing Federal and State regulations, and Veterinary Services’ current role in aquaculture. Principal Aquaculture Species There are five principal aquaculture fish species in the U.S. (catfish, trout, salmon, tilapia, and hybrid striped bass) and two categories of non-food fish production (baitfish and ornamental fish). Contribution to total aquaculture production of other fish species such as walleye, sunfish, and largemouth bass is rather limited. -

Atlantic Salmon Salmo Salar

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar Lake Ontario population in Canada EXTIRPATED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic salmon Salmo salar (Lake Ontario population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 26 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Patricia Edwards for writing the status report on the Atlantic Salmon (Lake Ontario population) in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources for the preparation of this report. Mart Gross and Michelle Herzog have edited and prepared sections of the report, and the COSEWIC report review was overseen by Mart Gross, Co-chair (Marine Fishes) and Paul Bentzen of the COSEWIC Marine Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee, with input from members of COSEWIC. That review may have resulted in changes and additions to the initial version of the report For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le saumon atlantique (population du lac Ontario) (Salmo salar) au Canada. -

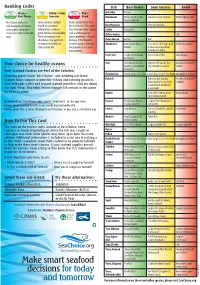

Make Smart Seafood Decisions for Today and Tomorrow

Ranking Codes Fish Best Choice Some Concerns Avoid Green = Yellow = Some Red = Arctic Char Farmed Recommended Best Choice Some Concerns Avoid Best Choice Concerns Avoid Barramundi Farmed, Closed Sys (US), Farmed, Closed Sys (Australia) Farmed, Open Sys (All) Australis (Vietnam) Best Choice seafood is Some Concerns seafood Avoid seafood items from well managed, abundant, should be consumed this list for now. They come Basa/Pangasius (Vietnam/Cambodia) and caught or farmed in infrequently, or when a from farmed or wild sources Catfish Farmed (US) environmentally sustainable green choice is not available. with a combination of Chilean Seabass (All) ways. There are concerns with critical problems—habitat abundance, management, damage, lethal impacts Clams /Mussels Farmed Wild or impacts on habitat or on other species, critically Atlantic Cod Hook and Line (Russia, Hook and Line (US Georges Bank All Other (Canada/US) other marine life. low populations, or poor Iceland) & Canada exc Georges Bank), management. Trawl (Russia, Iceland) Pacific Cod Longline, Pot, Hook and Bottom Trawl (US/BC) (Russia/Japan) Line (Alaska) Crab Snow (Alaska, Gulf of St. Dungeness (US/Canada), King King (Russia), Jonah (US/ Your choice for healthy oceans Lawrence), Stone (Florida/ (US), Snow (Rest of Canada) Canada) US Atlantic) Your Seafood Choices are Part of the Solution. Flounder/Sole Several options exist across all colour categories, please visit SeaChoice.org for more detail Choosing green-listed “Best Choice” and avoiding red-listed seafood helps support responsible fishing and farming practices. Haddock Bottom Longline (Canada), Handline, Trawl (US Gulf Bottom Trawl (US Georges Bank/ of Maine) Vote with your wallet and reward seafood providers who are doing Canada/Iceland), Handline (US the right thing. -

Determining Natal Origin for Improved Management of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS 439 Determining natal origin for improved management of Atlantic bluefin tuna Naiara Rodríguez-Ezpeleta1*, Natalia Díaz-Arce1, John F Walter III2, David E Richardson3, Jay R Rooker4, Leif Nøttestad5, Alex R Hanke6, James S Franks7, Simeon Deguara8, Matthew V Lauretta2, Piero Addis9, Jose Luis Varela10,11, Igaratza Fraile1, Nicolas Goñi1, Noureddine Abid12, Francisco Alemany13, Isik K Oray14, Joseph M Quattro15, Fambaye N Sow16, Tomoyuki Itoh17, F Saadet Karakulak14, Pedro J Pascual-Alayón18, Miguel N Santos19, Yohei Tsukahara17, Molly Lutcavage20, Jean-Marc Fromentin21, and Haritz Arrizabalaga1 Effective sustainable management of marine fisheries requires that assessed management units (that is, fish stocks) correspond to biological populations. This issue has long been discussed in the context of Atlantic bluefin tuna (ABFT, Thunnus thynnus) man- agement, which currently considers two unmixed stocks but does not take into account how individuals born in each of the two main spawning grounds (Gulf of Mexico and Mediterranean Sea) mix in feeding aggregations throughout the Atlantic Ocean. Using thousands of genome-wide molecular markers obtained from larvae and young of the year collected at the species’ main spawning grounds, we provide what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first direct genetic evidence for “natal homing” in ABFT. This has facilitated the development of an accurate, cost-effective, and non-invasive tool for tracing the genetic origin of ABFT that allows for the assignment of catches to their population of origin, which is crucial for ensuring that ABFT management is based on biologically meaningful stock units rather than simply on catch location. Front Ecol Environ 2019; 17(8): 439–444, doi:10.1002/fee.2090 ommercial fisheries make important contributions to the stocks (management units) are critical (Musick and Bonfil C economies of many countries, as well as to human well- 2005). -

Farmed Or Wild? Both Types of Salmon Are Good and Good For

marketplace Farmed Or Wild? Both Types Of Salmon Taste Good And Are Good For You Pamela D. Tom University of California – Davis Sea Grant Extension Program Food Science and Technology Department 1 Shields Avenue Davis, California 95616 USA [email protected] Paul G. Olin University of California Cooperative Extension Sea Grant Extension Program Santa Rosa, California, USA 95403 and their commercial harvest is limited. Farm-raised fish are hatched, raised and harvested under controlled conditions com- parable to other farmed animals. Farmed Atlantic salmon are available year-round in fresh or frozen forms. Most wild-caught salmon are one of five species of Pacific salmon. They are harvested by fishing with a variety of gear Farm-raised Atlantic salmon are raised and harvested under types, mostly in the north Pacific from June through September. controlled conditions that provide a year-round supply of fish. Fresh wild Pacific salmon are available during this time. The rest Photo courtesy of the British Columbia Salmon Farmers of the year, frozen or canned wild salmon are available. Association. How are farmed and wild salmon similar? Farmed and wild salmon have very similar nutrients. Atlantic Summary: salmon and Pacific salmon look similar on the outside. But Whether farmed or wild, salmon are tasty fish and a between species and even within the same species, each type of healthy protein choice. They look and taste nearly the salmon can have different flavors, textures and flesh color. How same. Wild Pacific salmon are harvested by fishing, the fish is processed and handled can also dramatically influence mostly in the north Pacific from June through Septem- these characteristics. -

Fish Stocks United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

General situation of world fish stocks United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Contents: 1. Definitions 2. Snapshot of the global situation 3. Short list of "depleted" fish stocks 4. Global list of fish stocks ranked as either "overexploited," "depleted," or recovering by region 1. Definitions Underexploited Undeveloped or new fishery. Believed to have a significant potential for expansion in total production; Moderately exploited Exploited with a low level of fishing effort. Believed to have some limited potential for expansion in total production; Fully exploited The fishery is operating at or close to an optimal yield level, with no expected room for further expansion; Overexploited The fishery is being exploited at above a level which is believed to be sustainable in the long term, with no potential room for further expansion and a higher risk of stock depletion/collapse; Depleted Catches are well below historical levels, irrespective of the amount of fishing effort exerted; Recovering Catches are again increasing after having been depleted 2. Snapshot of the global situation Of the 600 marine fish stocks monitored by FAO: 3% are underexploited 20% are moderately exploited 52% are fully exploited 17% are overexploited 7% are depleted 1% are recovering from depletion Map of world fishing statistical areas monitored by FAO Source: FAO's report "Review of the State of World Marine Fisheries Resources", tables D1-D17, ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/007/y5852e/Y5852E23.pdf 3. Fish stocks identified by FAO as falling into its