Preventing Suicide a Resource for General Physicians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Suicide

History of suicide In general, the pagan world, both Roman and Greek, had a relaxed attitude towards the concept of suicide, a practice that was only outlawed with the advent of the Christians, who condemned it at the Council of Arles in 452 as the work of the Devil. In the Middle Ages, the Church had drawn-out discussions on the edge where the search for martyrdom was suicidal, as in the case of some of the martyrs of Córdoba. Despite these disputes and occasional official rulings, Catholic doctrine was not entirely settled on the subject of suicide until the later 17th century. There are some precursors of later Christian hostility in ancient Greek thinkers. Pythagoras, for example, was against the act, though more on mathematical than moral grounds, believing that there was only a finite number of souls for use in the world, and that the sudden and unexpected departure of one upset a delicate balance. Aristotle also condemned suicide, though for quite different, far more practical reasons, in that it robbed the community of the services of one of its members. A reading of Phaedo suggests that Plato was also against the practice, inasmuch as he allows Socrates to defend the teachings of the Orphics, who believed that the human body was the property of the gods, and thus self-harm was a direct offense against divine law. The death of Seneca (1684), painting by Luca Giordano, depicting the suicide of Seneca the Younger in Ancient Rome. In Rome, suicide was never a general offense in law, though the whole approach to the question was essentially pragmatic. -

Suicide Research: Selected Readings. Volume 2

SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page i SUICIDE RESEARCH: SELECTED READINGS Volume 2 May 2009–October 2009 J. Sveticic, K. Andersen, D. De Leo Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention National Centre of Excellence in Suicide Prevention SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page ii First published in 2009 Australian Academic Press 32 Jeays Street Bowen Hills Qld 4006 Australia www.australianacademicpress.com.au Reprinted in 2010 Copyright for the Introduction and Comments sections is held by the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, 2009. Copyright in all abstracts is retained by the current rights holder. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior permission from the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. ISBN: 978-1-921513-53-4 SuicideResearchText-Vol2:SuicideResearchText-Vol2 8/6/10 11:00 AM Page iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments ..............................................................................viii Introduction Context ..................................................................................................1 Methodology ........................................................................................2 Key articles Alexopoulos et al, 2009. Reducing suicidal ideation -

Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative

PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Preventing suicide: a global imperative. 1.Suicide, Attempted. 2.Suicide - prevention and control. 3.Suicidal Ideation. 4.National Health Programs. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 156477 9 (NLM classification: HV 6545) © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility The designations employed and the presentation of the material in for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning arising from its use. -

The Right to Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia

THE RIGHT TO ASSISTED SUICIDE AND EUTHANASIA NEIL M. GORSUCH* I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 600 I. THE COURTS ............................................................. 606 A. The Washington Due Process Litigation............ 606 1. The Trial Court ...................... 606 2. The Ninth Circuit Panel Decision ............. 608 3. The En Banc Court ...................................... 609 B. The New York Equal ProtectionLitigation ........ 611 1. The Trial Court ........................................... 611 2. The Second Circuit ..................................... 612 C. The Supreme Court............................................. 613 1. The Majority Opinion ................................. 614 2. The Concurrences ....................................... 616 D. The Consequences ofGlucksberg and Quill .... 619 III. ARGUMENTS FROM HISTORY ................................... 620 A. Which History?................................................... 620 B. The Ancients ....................................................... 623 C. Early Christian Thinkers .................................... 627 D. English Common Law ......................................... 630 E. ColonialAmerican Experience........................... 631 F. The Modern Consensus: Suicide ........................ 633 G. The Modern Consensus: Assisting Suicide and Euthanasia.......................................................... 636 IV. ARGUMENTS FROM FAIRNESS .................................. 641 A . Causation........................................................... -

National Guidelines: Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide

Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force April 2015 Blank page Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Table of Contents Front Matter Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... i Task Force Co-Leads, Members .................................................................................................................. ii Reviewers .................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... iii National Guidelines Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Terminology: “Postvention” and “Loss Survivor” ....................................................................................... 4 Development and Purpose of the Guidelines ............................................................................................. 6 Audience of the Guidelines ........................................................................................................................ -

National Study of Jail Suicide: 20 Years Later Foreword

U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections 320 First Street, NW Washington, DC 20534 Morris L. Thigpen Director Thomas J. Beauclair Deputy Director Virginia A. Hutchinson Chief, Jails Division Fran Zandi Program Manager National Institute of Corrections www.nicic.gov Lindsay M. Hayes, Project Director National Center on Institutions and Alternatives April 2010 NIC Accession Number 024308 This document was prepared under cooperative agreement number 06J47GJM0 from the National Institute of Corrections, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ..............................................................................................ix Executive Summary ............................................................................................xi Chapter 1. Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 Prior Jail Suicide Research .................................................................................... 2 A Word About Suicide Victim Profiles .................................................................... 3 Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000............................................................... -

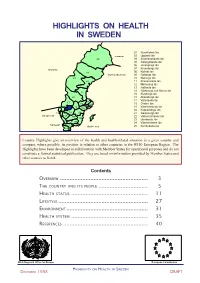

Sweden Part 1

HIGHLIGHTS ON HEALTH IN SWEDEN 01 Stockholms län 03 Uppsala län Finland 25 04 Södermanlands län 05 Östergötlands län 06 Jönköpings län 07 Kronobergs län Norway 08 Kalmar län 24 Gulf of Bothnia 09 Gotlands län 23 10 Blekinge län 22 11 Kristianstads län 12 Malmöhus län 13 Hallands län 14 Göteborgs och Bohus län 21 15 Älvsborgs län 20 16 Skaraborgs län 17 Värmlands län 17 03 18 Örebro län 19 01 18 19 Västmanlands län 04 20 Kopparbergs län 14 16 05 21 Gävleborgs län Skagerrak 15 06 22 Västernorrlands län 08 09 23 Jämtlands län 13 07 24 Västerbottens län Kattegat 11 10 Baltic sea 25 Norrbottens län 12 Country Highlights give an overview of the health and health-related situation in a given country and compare, where possible, its position in relation to other countries in the WHO European Region. The Highlights have been developed in collaboration with Member States for operational purposes and do not constitute a formal statistical publication. They are based on information provided by Member States and other sources as listed. Contents OVERVIEW ....................................................... 3 THE COUNTRY AND ITS PEOPLE ............................... 5 HEALTH STATUS ................................................ 11 LIFESTYLE ........................................................ 27 ENVIRONMENT ................................................... 31 HEALTH SYSTEM ................................................ 35 REFERENCES ..................................................... 40 WHO Regional Office for Europe European Commission -

Understanding Risk & Protective Factors for Suicide

Understanding Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide: A Primer for Preventing Suicide Risk and protective factors play a critical role in suicide prevention. For clinicians, identifying risk and protective factors provides critical information to assess and manage suicide risk in individuals. For communities and prevention programs, identifying risk and protective factors provides direction about what to change or promote. Many lists of risk factors are available throughout the field of suicide prevention. This paper provides a brief overview of the importance of risk and protective factors as they relate to suicide and offers guidance about how communities can best use them to decrease suicide risk. Contents: What are risk and protective factors? Risk factors are not warning signs. What are major risk and protective factors for suicide? Why are risk and protective factors important? Using risk and protective factors in the strategic planning process Key points about risk and protective factors for suicide prevention Additional resources Further reading References What are risk and protective factors? Risk factors are characteristics that make it more likely that individuals will consider, attempt, or die by suicide. Protective factors are characteristics that make it less likely that individuals will consider, attempt, or die by suicide. Risk and protective factors are found at various levels: individual (e.g., genetic predispositions, mental disorders, personality traits), family (e.g., cohesion, dysfunction), and community (e.g., availability of mental health services). They may be fixed (those things that cannot be changed, such as a family history of suicide) or modifiable (those things that can be changed, such as depression). -

Suicides in Massachusetts 2017

Suicides in Massachusetts 2017 December 2020 Legislative Mandate The following report is hereby issued pursuant to Section 232 of Chapter 111 of the Massachusetts General Laws as follows: The department, in consultation with the executive office of public safety and security shall, subject to appropriation, collect, record and analyze data on all suicides in the Commonwealth. Data collected for each incident shall include, to the extent possible and with respect to all applicable privacy protection laws, the following: (i) the means of the suicide; (ii) the source of the means of the suicide; (iii) the length of time between purchase of the means and the death of the decedent; (iv) the relationship of the owner of the means to the decedent; (v) whether the means was legally obtained and owned pursuant to the laws of the commonwealth; (vi) a record of past suicide attempts by the decedent; and (vii) a record of past mental health treatment of the decedent. The department shall annually submit a report, which shall include aggregate data collected for the preceding calendar year and the department’s analysis, with the clerks of the House of Representatives and the Senate and the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security not later than December 31. Names, addresses or other identifying factors shall not be included. The commissioner shall work in conjunction with the offices and agencies in custody of the data listed in this section to facilitate collection of the data and to ensure that data sharing mechanisms are in compliance with all applicable laws relating to privacy protection. -

Physician Suicide: a Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention

GLOBAL PSYCHIATRY — Vol 3 | Issue 2 | 2020 Tiffany I. Leung, MD, MPH, FACP, FAMIA1*, Rebecca Snyder, MSIS2, Sima S. Pendharkar, MD, MPH, FACP3‡, Chwen-Yuen Angie Chen, MD, FACP, FASAM4‡ Physician Suicide: A Scoping Literature Review to Highlight Opportunities for Prevention 1Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences, Department of Internal Medicine, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands 2Library Services, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA 3Division of Hospital Medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Icahn School of Medicine Mt. Sinai, Brooklyn, NY, USA 4Department of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA *email: [email protected] ‡Indicates equal contributions as last authors to the production of this manuscript. DOI: 10.2478/gp-2020-0014 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020 Abstract Objective: The aim of this scoping review is to map the current landscape of published research and perspectives on physician suicide. Findings could serve as a roadmap for further investigations and potentially inform efforts to prevent physician suicide. Methods: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for English-language publications from August 21, 2017 through April 28, 2018. Inclusion criteria were a primary outcome or thesis focused on suicide (including suicide completion, attempts, and thoughts or ideation) among medical students, postgraduate trainees, or attending physicians. Opinion articles were included. Studies that were non-English or those that only mentioned physician burnout, mental health, or substance use disorders were excluded. Data extraction was performed by two authors. Results: The search yielded 1,596 articles, of which 347 articles passed to the full-text review round. -

Season of Birth in Suicidology

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, SE-901 85 Umeå, Sweden SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies Jayanti Chotai Umeå 1999 UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 604 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. From the Division of Psychiatry, Department of Clinical Science, Umeå University, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. SEASON OF BIRTH IN SUICIDOLOGY Neurobiological and epidemiological studies AKADEMISK AVHANDLING som med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet for avläggande av medicine doktorsexamen kommer att offentligen försvaras i Sal B, 9 tr, Tandläkarhögskolan, Norrlands universitetssjukhus, Umeå, fredagen den 28 maj 1999, kl 13.00 av Jayanti Chotai 1 v. *5 <J> va Fak ultetsopponent: Professor Hans Ågren, Karolinska institutet, Sektionen för psykiatri, Huddinge sjukhus Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Medical Science in Psychiatry presented at Umeå University in 1999. ABSTRACT Chotai J (1999). Season of birth in suicidology: neu robiologies and epidemiological studies. Umeå University, Department of Clinical Science, Division of Psychiatry, 901 85 Umeå, Sweden. ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 91-7191-645-8. Barkpround: Several neuropsychiatrie disorders have shown season of birth associations. Low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA and the dopamine metabolite HVA have been associated with suicidal behaviour, impulsivity, and aggression. This thesis investigated associations between the season of birth, the CSF levels of three monoamine metabolites (including MHPG of norepinephrine), the scales of the diagnostic interview for borderline patients (DIB), and psychiatric diagnoses. -

State of Connecticut Suicide Prevention Plan 2020-2025

Be the 1to start the conversation STATE OF CONNECTICUT SUICIDE PREVENTION PLAN 2020-2025 DEDICATION This plan and the associated efforts to prevent suicide and build lives worth living are dedicated to the Connecticut residents, families, friends, and communities who are all affected in profound ways by suicide. Are you having suicidal thoughts? Suicidal thoughts by themselves aren’t dangerous, but how you respond to them can make all the difference. Support is available. Anyone can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at 800- 273-8255 (en español, 1-888-628-9454; TTY, 1-800- 799-4889). Press 1 for the Veterans Crisis Line. In Connecticut, call 211 for National Suicide Prevention Lifeline services, or youth or adult mobile crisis services. Don’t feel like talking on the phone? Try Lifeline Crisis Chat (www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/chat) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME or CT to 741741 or the Veterans Crisis Line by texting 838255. If you want to plan ahead to help you stay safer in the future, download the My3 App from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. You can use the app to list your crisis contacts, make a safety plan, and use emergency resources. For more information, look in your phone’s app store or go to https://my3app.org/ Are you concerned someone else might be at risk of suicide? This person is fortunate you are paying attention. Here are five easy steps you can take to help: 1. Show you care. This looks different depending on who you are and your relationship, but let the person know you have noticed something has changed and that their well-being matters to you.