Books and Reading Year 2005 News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture, Language & Politics

Eleni Ganiti ([email protected]) PhD candidate in Art History, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of History and Archaeology, Faculty of Philosophy The Military Dictatorship of April 1967 in Greece and its repercussion on the Greek visual arts scene. Introduction The 21st of April, 1967 has been a portentous date in the history of modern Greece, as a group of right – wing army officers seized power, imposing a regime of military dictatorship, also known as the Regime of the Colonels or the Junta. The dictatorship came after a period of political instability in the country, intercepting the normal course of things at the political, social and economical sector. Obviously this kind of disorder could not leave the cultural life of the country unaffected. The imposing of the dictatorship had a strong impact on the evolution of the visual arts in Greece, mainly because it came at a time when Greek art, for the first time in the modern years, was finding its pace. The desire for synchronization with the international art was being finally fulfilled and for the first time Greek artists were part of the international avant guard. The visual arts scene was flourishing, the audience’s interest was growing and the future seemed promising and optimistic. Then the Junta came to interrupt this upswing. In this presentation we will attempt to explore: i) the effects of the dictatorship on the Greek visual arts scene and the artistic production of the period ii) the reaction of the art world mainly through exhibitions and works of Greek artists that were created and exhibited in the country during the seven years of the Military Regime. -

Leben Lieben Lesen*

60 YEARS Foreign Rights List Autumn 2012 * leben lieben lesen New books by Jakob Arjouni · Bielefeld & Hartlieb Otto A. Böhmer · Lukas Hartmann · Donna Leon Petros Markaris · Anthony McCarten Ingrid Noll · Liaty Pisani · Hansjörg Schneider living loving reading loving living Martin Suter and Tomi Ungerer * Theatre Awards Alfred Andersch Sławomir Mrożek The readers of BuchMarkt The Father of a Murderer Emigrants magazine voted: Theater tri-bühne, Stuttgart Asociata Tam-Tam, Bucharest Astrid Rosenfeld for 3rd Théâtre Mouff etard, Paris place as ›Author of the Year 2011‹ Friedrich Dürrenmatt Benedict Wells on the The Visit Patrick Süskind top ten in the same category Jokai Theater, Bekes The Double Bass Diogenes Verlag Stadttheater Bern TheArtTheater, Athens for ›Publisher of the Year 2011‹! Jozsef Attila Theater, Budapest Konzerthaus Berlin I. L. Caragiale National Theatre, Das Theater an der Friedrich Dürrenmatt Bucharest Effi ngerstrasse, Berne His Life in Pictures is awarded National Academic Drama Studio L + S, Bratislava one of the 27 ›Most Beautiful Theatre named Theater Ungelt, Prague Swiss Books 2011‹ by the Swiss aft er M. Gorki, Minsk Poweszechny Theater, Federal Offi ce of Culture. TeatroDue, Parma Radom Theatre Bonmal, Seoul Theatre of the Gran Area Petros Markaris Habimah Theatre, Tel Aviv Metropolitana, San José Received the ›VII Pepe Carvalho Theater Lubuski, Zielona Góra National Theater Award‹ in Barcelona for being Ivan Vazov, Sofi a one of the most representative Patricia Highsmith Ensemble Vicenza Teatro, authors of the Mediterranean The Talented Mr. Ripley Sovizzo mystery novel. Schaubühne am Lithuanian National Drama Lehniner Platz, Berlin Theatre, Vilnius Anthony McCarten Tomi Ungerer Television Death of a Superhero The Three Robbers Neues Junges Theater, ArtPlan, Tokyo Martin Suter Göttingen Director Markus Welter pictur- Luzerner Theater, Lucerne ised The Devil of Milan with Regula Grauwiller, Ina Weisse and Max Simonischek. -

My Typewriter on It Enab!Ing the Thought to Penetrate the Pillage of the Silence Writing

Études helléniques / Hellenic Studies Greek Immigrant Authors in Germany Niki Eideneier* Final/y one day 1 made up my mind. To grasp the tiny table to place it next to the window to instal! my typewriter on it enab!ing the thought to penetrate the pillage of the silence writing... Georges Lillis 1 RÉSUMÉ Traditionnellement l'Allemagne n'était pas un pays d'accueil d'immigrants mais bien de travailleurs invités {Garstarbeiter) dont plusieurs étaient d'origine grecque. Certains sont même devenus des écrivains exemplaires d'une littérature que certains appellent «d'immigration» parmi d'autres appellations. I..:article qui suit nous offre un rare survol de la scène littéraire de la diaspora grecque en Allemagne depuis l'après-guerre jusqu'à nos jours. De plus, l'auteur traite des différentes appellations données à cette littérature des immigrants présents dans le paysage littéraire de l'Allemagne et de la Grèce. ABSTRACT Germany may net be considered a country of immigration but it has certainly been a country of guest workers {Ga rstarbeiter). Many of these were Greek immigrants who were writers or became wrirers. Their literacure has been called 'immigration literature' among other labels. This article considers the various labels and describes the Greek immigrants active in the literary landscape of Germany and even Greece. The author provides a rare, sweeping overview of the scene from the early post-war period to coday. Introduction The Federal Republic of Germany is a country of 357,027 square kilometres and 82 million people. This study focuses on the image presented * Publisher 99 Études helléniques I Hellenic Studies by the Federal Republic of Germany, hereinafter called Germany for the purposes of this article, and its non-native population after the Second World War and more specifically from 1960 onwards. -

Female Emancipation in Sara Paretsky's VI Warshawski Novels

Out of Deadlock Out of Deadlock Female Emancipation in Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski Novels, and her Influence on Contemporary Crime Fiction Edited by Enrico Minardi and Jennifer Byron Out of Deadlock: Female Emancipation in Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski Novels, and her Influence on Contemporary Crime Fiction Edited by Enrico Minardi and Jennifer Byron This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Enrico Minardi, Jennifer Byron and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7431-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7431-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Crime Fiction, More than Mere Entertainment: The Role of the Crime Novel as a Platform for Gender-Negotiations on a Global Scale Enrico Minardi Chapter One ............................................................................................... 11 The Detective as Speech Sara Paretsky Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Following in the Footsteps of Sara Paretsky: -

Read Book Deadline in Athens : an Inspector Costas Haritos Mystery

DEADLINE IN ATHENS : AN INSPECTOR COSTAS HARITOS MYSTERY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Petros Markaris | 304 pages | 09 Aug 2005 | Grove Press / Atlantic Monthly Press | 9780802142078 | English | New York, United States Deadline in Athens : An Inspector Costas Haritos Mystery PDF Book You can still see all customer reviews for the product. Taktsis gives us both. Other suicides follow, the victims somehow linked by their part in protest against the Junta of I'm a character-driven reader, so those all-important fictional people mean a great deal to me. Toby Wilkinson on Ancient Egypt Books. All returns must be approved before an item is shipped back. Here, in another sturdy translation by David Connolly, a shady entrepreneur with rich building contracts for the Olympics kills himself in public. He was a writer and journalist, and a transvestite who would walk the streets and have sex for money. Die Zeit. How did that go down in Greece? DPReview Digital Photography. When a writer starts with a masterpiece it is very different to continue because of the fear that people will say the second novel is not as good. If my English were much better I would translate them myself because I think, even today, they would be understood by English readers as something special. For one thing, the two deaths seem to be connected. The item may be missing the original packaging such as the original box or bag or tags or in the original packaging but not sealed. One reason why I enjoy reading mysteries written by international authors is the opportunity to learn about other countries and cultures. -

Food Heritage and Nationalism in Europe

Food Heritage and Nationalism in Europe Edited by Ilaria Porciani First published 2019 ISBN: 978- 0- 367- 23415- 7 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 0- 429- 27975- 1 (ebk) Chapter 1 Food heritage and nationalism in Europe Ilaria Porciani (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Chapter 1 Food heritage and nationalism in Europe Ilaria Porciani Food: heritage for uncertain times More than ever, food occupies a central place in our thoughts and our imagin- ation. The less we cook or eat in a decent way, the more we are concerned with the meaning and strategies of cooking, the authenticity of recipes and their normative grammar. Food, the most accessible threshold of culture (La Cecla 1997 ), is ubiquitous in television series and programmes, fi lms (Saillard 2010 ), magazines, newspaper articles and novels (Biasin 1991 ; Ott 2011 ), as well as in recent and very popular detective stories. Commissario Montalbano, created by Andrea Camilleri, makes a point of praising the true Sicilian cooking of his housekeeper while despising the cuisine from distant, albeit Mediterranean, Liguria as prepared by his fi anc é e. The hero of Petros Markaris’s detective novels, Inspector Costas Charitos, a Rum – that is, a Greek born in Istanbul – explores contact zones and frictions between the often overlapping cuisines of the two communities. The detective created by Manuel V á squez Montá lban constantly describes local and national dishes from his country in vivid detail, and mirrors the tension between local, Catalan and national cuisine. Why should this be so if these attitudes did not speak immediately to everyone? In every culture, “foodways constitute an organized system, a language that – through its structure and components – conveys meaning and contributes to the organization of the natural and social world” (Counihan 1999 , 19). -

Perceptions of History in Germany and Greece

Perceptions of history in Germany and Greece Comparative approaches to narratives in the Euro- pean context Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften Fachbereich SLM II Perceptions of history Viele Disziplinen beschäftigen sich mit einer kompara- tiven Analyse der Wahrnehmung von Vergangenheit in Germany and Greece in Europa. Es gibt Vorurteile gegenüber ganze Völker und Nationen, auch Stereotype, die aus kollektiver historischer Erinnerung abgeleitet sind. Aktuelle Krisen haben diese Voreingenommenheit reaktiviert und in einem neuen Kontext mit neuen Bedeutungen belegt. Die sozialen und politischen Konsequenzen der aktu- Kontakt und Ansprechpartner ellen Staatsschuldenkrise haben neue Szenarien von Prof. Dr. Ulrich Moennig Schuldzuweisungen und Ressentiments geschaffen. Die Schwierigkeit, die komplexen wirtschaftlichen und Institut für Griechische und Lateinische Philologie politischen Zusammenhänge zu durchschauen, führen Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie zu vereinfachten gegenseitigen Wahrnehmungen, die Von-Melle-Park 6 den europäischen Einigungsprozess gefährden können. 20146 Hamburg Der Kongress Perceptions of history in Germany and https://www.slm.uni-hamburg.de/igrlatphil.html Greece: Comparative approaches to narratives in the European context (31. März – 2. April 2016) untersucht solche Zusammenhänge am Beispiel der gegenseiti- gen Wahrnehmung von Deutschen und Griechen in historischer Perspektive. Der Kongress ist interdiszipli- när, die Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmer kommen aus philologisch-literaturwissenschaftlichen (Klassische -

Joining the Dots in Translation History: the First Brecht Poetry Anthologies in Greece Dimitris Asimakoulas

Joining the dots in translation history: the first Brecht poetry anthologies in Greece Dimitris Asimakoulas Abstract The important questions any project on translation history may ask can be distilled into three basic queries: Where can change be observed? Which intermediaries are involved? What materials are relevant? This article focuses on an important transitional moment, the move from preventive censorship to ostensible freedom of expression in Greece in 1970, and on the publication of two anthologies of Brecht's poetry, the least studied genre of his oeuvre. A critical, mixed approach of combining mediated sources (interviews, memoirs) with less mediated sources (archives, texts) in a context of low documentation culture challenges established views: quantities in the flows of cultural products are impervious to flat interpretations and translations can indeed be more political than original writing. The paratextual framing, linguistic presentation, selection and ordering of a corpus of 86 poems shows precisely that. The two anthologies under consideration constituted a whole that was greater than its parts, and were prepared by intermediaries with an emerging habitus of cultural ambassadorship. Key words: anthology, censorship, Greek, ideology, poetry, translation history 1. History: a Rosetta Stone question An increase of translation activity may often be associated with significant shifts in a given cultural space. According to a translation history project that started in the 1990s and whose aim is to chart translation flows in Greece (19th century onwards), one of the major 20th century milestones is the period following 1968, when evidence of increased translation activity may be observed (Kasines 1998). The project is still in process and has not provided answers as to what this growth meant or whether/how it was affected by censorship. -

Political Theatre in Times of Crisis. Case Study: Our Grand Circus, a Greek Example of Epic Theatre

Political theatre in times of crisis. Case Study: Our Grand Circus, a Greek example of epic theatre. Afroditi Spyropoulou Student number: 4190068 Tutor: Dr. Sigrid Merx Second reader: Dr. Konstantina Georgelou University of Utrecht MA Thesis 2015 15/8/2015 1 Foreword I would like to express my gratitude to the people without whom this Thesis would have never been completed. First and foremost my husband, Ciro, for his support in all aspects. Konstantina Georgelou that provided her feedback in the beginning of the Thesis with her sharp view and mostly for her own initiative to mail Dr. Philip Hager and ask for some insight. Philip Hager sent his dissertation and the article on which I based the whole subchapter about Greek dramaturgy in the beginning of the 1970s. I thank them both and I am grateful of their help. Last but not least I thank my tutor Sigrid Merx that with her kindness and patience taught me from scratch how to write academically, maintaining her calmness every time I postponed a deadline. Without her precious help I would have never finished my studies in the Utrecht University. 2 Abstract This Thesis attempts to classify the play Our Grand Circus, a symbol of the Greek 7 years long dictatorship of the middle of 1970’s. The economic crisis and political oppression that started in Greece in 2010 brought this play again onto the Greek stages after 40 years of absence, reminding the success it had back in the ‘70s. Still, though, the play remains under the vague umbrella of “political theatre”. -

World Court of Human Rights: Utopia?

1 | 2012 GLOBAL Preis: VIEW 3,– Euro Unabhängiges Magazin der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Außenpolitik und die Vereinten Nationen (ÖGAVN) und des Akademischen Forums für Außenpolitik (AFA) World Court of Human Rights: Utopia? http://www.globalview.at DVR: 0875538 Nr.1/2012; ISSN: 1992-9889 Liebe Leserin! Lieber Leser! Die Idee zur Einrichtung eines Weltgerichts- tikel. Mit der Ausrichtung der Global South- hofes für Menschenrechte ist zwar nicht South Development Expo (GSSD) Ende des neu, jedoch haben jüngste Entwicklungen Jahres wird die Partnerschaft einen neuen die Diskussion darüber wieder neu entfacht. Höhepunkt erreichen. Trotz mancher regional erfolgreicher Mo- Ab 2014 soll der Louvre Abu Dhabi dank delle und zahlreicher Abkommen betrachten des klangvollen Namens, hochkarätiger viele Regierungen, aber auch einige NGOs, Kunstwerke und eindrucksvoller Architektur eine weltweit agierende Instanz in Sachen Besucher aus aller Welt an den Persischen Menschenrechte als eine zu radikale oder Golf locken. Das arabische Emirat scheint gar utopische Vorstellung. Prof. Manfred keine Kosten und Mühen zu scheuen, um Nowak präsentiert in seinem Artikel stich- sich den Glanz eines weltberühmten Muse- haltige Argumente für einen Weltgerichts- ums zu verleihen. Wie Nicole Kanne berich- hof für Menschenrechte und beantwortet tet, beobachten Kritiker das Projekt mit wichtige Fragen, um der weit verbreiteten Argwohn, orten sie doch eine zunehmende Skepsis zu begegnen. Kommerzialisierung von Museen. „Der Kern der Probleme liegt für mich im Die vielfältige Kultur Österreichs als Kern- politischen System, im Versagen der poli- element der Außenpolitik zu präsentieren, tischen Kultur und der politischen Klasse in stellt eine besondere Herausforderung dar. Griechenland.“ Mit diesen eindringlichen Botschafter Martin Eichtinger zeigt, wie sich Worten beschreibt der griechische Autor die österreichische Auslandskulturpolitik Petros Markaris die Situation in seinem süd- auf Basis des neuen, 2011 verabschiede- europäischen Heimatland. -

Critical Times, Critical Thoughts

Critical Times, Critical Thoughts Critical Times, Critical Thoughts: Contemporary Greek Writers Discuss Facts and Fiction Edited by Natasha Lemos and Eleni Yannakakis Critical Times, Critical Thoughts: Contemporary Greek Writers Discuss Facts and Fiction Edited by Natasha Lemos and Eleni Yannakakis This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Natasha Lemos, Eleni Yannakakis and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8274-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8274-3 Dedicated to the memory of Niki Marangou TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Preface ........................................................................................... x Introduction Eleni Yannakakis and Natasha Lemos ......................................................... 1 Part I: The Other Chapter One ............................................................................................... 20 To Be or not to Be an Organic Intellectual When Fascism Is Repeated as Farce? The Case of Contemporary Greece Angela Dimitrakaki Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

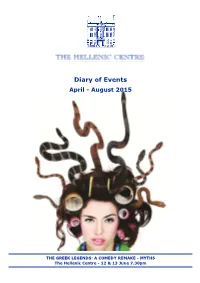

Diary of Events

Diary of Events April - August 2015 THE GREEK LEGENDS: A COMEDY REMAKE - MYTHS The Hellenic Centre - 12 & 13 June 7.30pm APRIL Wednesday 18 March to Friday 24 April - Friends Room, Hellenic Centre Diving An exhibition of paintings by Evangelia Ronga, evoking the crystal clarity of water and creating an image of the colour blue, which is strongly associated with the natural environment of Greece. For opening hours call 020 7487 5060. Supported by the Hellenic Centre. Wednesday 1 April, 7.30pm - Friends Room, Hellenic Centre Recital with Fusionia Duo Marios Ioannou and Savvas Lagou perform a programme that includes works for two violins by Prokofiev, Bella Bartok, Henryk Wieniawski as well as the world premiere of Clouds by Vasileios Philippou. Free entry; booking essential on 020 7563 9835 or at [email protected]. Organised by the Hellenic Centre. Saturday 18 April, 7pm - Great Hall, Hellenic Centre Rachmaninoff - Variations in a Life Costas Fotopoulos interprets the music of the com- poser who bridged the gap between the romantic and the modernists; Alberto Bona presents Rachmaninoff himself; script written by Josephine Hammond. Free entry; booking essential on 020 7563 9835 or at [email protected]. Organised by the Hellenic Centre. Wednesday 22 April, 7.15pm - Friends Room, Hellenic Centre Reputation in the Digital Age - What is your Online Identity? Information technology expert Konstantinos Varsis, discusses in English, how our online presence and digital footprint affect our everyday lives and what we can do to be in control. Free entry; booking essential on 020 7563 9835 or at [email protected]. Organised by the Hellenic Centre.