Avant 12012 Online.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

POPPER's GEWÖHNUNGSTHEORIE ASSEMBLED and FACED with OTHER THEORIES of LEARNING1 Arne Friemuth Petersen2

POPPER’S GEWÖHNUNGSTHEORIE ASSEMBLED AND FACED WITH OTHER THEORIES OF LEARNING1 Arne Friemuth Petersen2 Former Professor of General Psychology University of Copenhagen Abstract. With the publication of Popper’s Frühe Schriften (2006), renewed possibilities for inquiring into the nature and scope of what may be termed simply ‘Popperian Psychology’ have arisen. For although Popper would never have claimed to develop such psychology there is, however, from his earliest to his last works, a wealth of recommendations as to how to come to grips with problems of the psyche without falling victim of inductivist and subjectivist psychology. The fact that most theories of learning, both traditional and modern, have remained inductivist, and therefore logically invalid, places Popper’s hypothetico- deductive approach to learning and the acquisition of knowledge among the most important conjectures in that entire domain, akin to Edelman’s biological theory of consciousness. Central to Popper’s approach and his final rejection of all inductive procedures is his early attempt at a theory of habit-formation, Gewöhnungstheorie (in ‘Gewohnheit’ und ‘Gesetzerlebnis’ in der Erziehung, 1927) – a theory not fully developed at the time but nevertheless of decisive importance for his view on education and later works on epistemology, being ‘of lasting importance for my life’ (2006, p. 501). Working from some of the original descriptions and examples in ‘Gewohnheit’ und ‘Gesetzerlebnis’, updated by correspondence and discussions with Popper this paper presents a tentative reconstruction of his Gewöhnungstheorie, supplemented with examples from present-day behavioural research on, for example, ritualisation of animal and human behaviour and communication (Lorenz), and briefly confronted with competing theories, notably those by representatives of the behaviourist tradition of research on learning (Pavlov and Kandel). -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

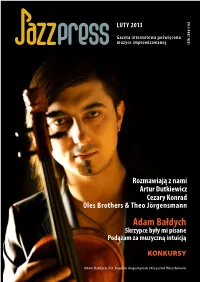

Jazzpress 0213

LUTY 2013 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej 2084-3143 ISSN Rozmawiają z nami Artur Dutkiewicz Cezary Konrad Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann Adam Bałdych Skrzypce były mi pisane Podążam za muzyczną intuicją KONKURSY Adam Bałdych, fot. Bogdan Augustyniak i Krzysztof Wierzbowski SPIS TREŚCI 3 – Od Redakcji 40 – Publicystyka 40 Felieton muzyczny Macieja Nowotnego 4 – KONKURSY O tym, dlaczego ona tańczy NIE dla mnie... 6 – Co w RadioJAZZ.FM 42 Najciekawsze z najmniejszych w 2012 6 Jazz DO IT! 44 Claude Nobs 12 – Wydarzenia legendarny twórca Montreux Jazz Festival 46 Ravi Shankar 14 – Płyty Geniusz muzyki hinduskiej 14 RadioJAZZ.FM poleca 48 Trzeci nurt – definicja i opis (część 3) 16 Nowości płytowe 50 Lektury (nie tylko) jazzowe 22 Pod naszym patronatem Reflektorem na niebie wyświetlimy napis 52 – Wywiady Tranquillo 52 Adam Baldych 24 Recenzje Skrzypce były mi pisane Walter Norris & Leszek Możdżer Podążam za muzyczną intuicją – The Last Set Live at the a – Trane 68 Cezary Konrad W muzyce chodzi o emocje, a nie technikę 26 – Przewik koncertowy 77 Co słychać u Artura Dutkiewicza? 26 RadioJAZZ.FM i JazzPRESS zapraszają 79 Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann 27 Koncerty w Polsce Transgression to znak, że wspięliśmy się na 28 Nasi zagranicą nowy poziom 31 Ulf Wakenius & AMC Trio 33 Oleś Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann tour 83 – BLUESOWY ZAUŁEK Obłędny klarnet w magicznym oświetleniu 83 29 International Blues Challenge 35 Extra Ball 2, czyli Śmietana – Olejniczak 84 Magda Piskorczyk Quartet 86 T-Bone Walker 37 Yasmin Levy w Palladium 90 – Kanon Jazzu 90 Kanon w eterze Music for K – Tomasz Stańko Quintet The Trio – Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen 95 – Sesje jazzowe 101 – Redakcja Możesz nas wesprzeć nr konta: 05 1020 1169 0000 8002 0138 6994 wpłata tytułem: Darowizna na działalność statutową Fundacji JazzPRESS, luty 2013 Od Redakcji Czas pędzi nieubłaganie i zaskakująco szybko. -

The Piano Equation

Edward T. Cone Concert Series ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE 2020–2021 Matthew Shipp The Piano Equation Saturday, November 21 2020 8:00 p.m. ET Virtual Concert, Live from Wolfensohn Hall V wo i T r n tu so osity S ea Institute for Advanced Study 2020–2021 Edward T. Cone Concert Series Saturday, November 21, 2020 8:00 p.m. ET MATTHEW SHIPP PROGRAM THE PIANO EQUATION Matthew Shipp Funding for this concert is provided by the Edward T. Cone Endowment and a grant from the PNC Foundation. ABOUT THE MUSIC David Lang writes: Over the summer I asked Matthew Shipp if he would like to play for us the music from his recent recording The Piano Equation. This album came out towards the beginning of the pandemic and I found myself listening to it over and over—its unhurried wandering and unpredictable changes of pace and energy made it a welcome, thoughtful accompaniment to the lockdown. My official COVID soundtrack. Matthew agreed, but he warned me that what he would play might not sound too much like what I had heard on the recording. This music is improvised, which means that it is different every time. And of course, that is one of the reasons why I am interested in sharing it on our season. We have been grouping concerts under the broad heading of ‘virtuosity’–how music can be designed so that we watch and hear a musical problem being overcome, right before our eyes and ears. Improvisation is a virtuosity all its own, a virtuosity of imagination, of flexibility, of spontaneity. -

INMUNOTERAPIA CONTRA EL CÁNCER ESPECIAL Inmunoterapia Contra El Cáncer

ESPECIAL INMUNOTERAPIA CONTRA EL CÁNCER ESPECIAL Inmunoterapia contra el cáncer CONTENIDO Una selección de nuestros mejores artículos sobre las distintas estrategias de inmunoterapia contra el cáncer. Las defensas contra el cáncer El científico paciente Karen Weintraub Katherine Harmon Investigación y Ciencia, junio 2016 Investigación y Ciencia, octubre 2012 Desactivar el cáncer Un interruptor Jedd D. Wolchok Investigación y Ciencia, julio 2014 para la terapia génica Jim Kozubek Investigación y Ciencia, mayo 2016 Una nueva arma contra el cáncer Viroterapia contra el cáncer Avery D. Posey Jr., Carl H. June y Bruce L. Levine Douglas J. Mahoney, David F. Stojdl y Gordon Laird Investigación y Ciencia, mayo 2017 Investigación y Ciencia, enero 2015 Vacunas contra el cáncer Inmunoterapia contra el cáncer Eric Von Hofe Lloyd J. Old Investigación y Ciencia, diciembre 2011 Investigación y Ciencia, noviembre 1996 EDITA Prensa Científica, S.A. Muntaner, 339 pral. 1a, 08021 Barcelona (España) [email protected] www.investigacionyciencia.es Copyright © Prensa Científica, S.A. y Scientific American, una división de Nature America, Inc. ESPECIAL n.o 36 ISSN: 2385-5657 En portada: iStock/royaltystockphoto | Imagen superior: iStock/man_at_mouse Takaaki Kajita Angus Deaton Paul Modrich Arthur B. McDonald Shuji Nakamura May-Britt Moser Edvard I. Moser Michael Levitt James E. Rothman Martin KarplusMÁS David DE J. 100 Wineland PREMIOS Serge Haroche NÓBEL J. B. Gurdon Adam G.han Riess explicado André K. Geim sus hallazgos Carol W. Greider en Jack W. Szostak E. H. Blackburn W. S. Boyle Yoichiro Nambu Luc MontagnierInvestigación Mario R. Capecchi y Ciencia Eric Maskin Roger D. Kornberg John Hall Theodor W. -

Francis Crick Personal Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1k40250c No online items Francis Crick Personal Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2007, 2016 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Francis Crick Personal Papers MSS 0660 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Francis Crick Personal Papers Creator: Crick, Francis Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0660 Physical Description: 14.6 Linear feet(32 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 2 oversize folders, 4 map case folders, and digital files) Physical Description: 2.04 Gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1935-2007 Abstract: Personal papers of British scientist and Nobel Prize winner Francis Harry Compton Crick, who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers document Crick's family, social and personal life from 1938 until his death in 2004, and include letters from friends and professional colleagues, family members and organizations. The papers also contain photographs of Crick and his circle; notebooks and numerous appointment books (1946-2004); writings of Crick and others; film and television projects; miscellaneous certificates and awards; materials relating to his wife, Odile Crick; and collected memorabilia. Scope and Content of Collection Personal papers of Francis Crick, the British molecular biologist, biophysicist, neuroscientist, and Nobel Prize winner who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers provide a glimpse of his social life and relationships with family, friends and colleagues. -

Le Scienze». Qui Presentiamo Estratti Dalle Pubblicazioni Del Nostro Archivio Che Hanno Gettato Nuova Luce Sul Funzionamento Del Corpo

RAPPORTO LINDAU BIOLOGIA Come funziona il corpo I vincitori di premi Nobel hanno pubblicato 245 articoli su «Scientific American», molti dei quali tradotti su «Le Scienze». Qui presentiamo estratti dalle pubblicazioni del nostro archivio che hanno gettato nuova luce sul funzionamento del corpo. È il nostro tributo agli scienziati che si riuniranno in Germania per il sessantaquattresimo Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, dove 600 giovani ricercatori scambieranno risultati e idee con 38 premi Nobel per la fisiologia o la medicina A cura di Ferris Jabr – Illustrazioni di Sam Falconer IN BREVE Questa estate i premi Nobel per la promettenti scienziati sull’isola di pubblichiamo una selezione di Gli estratti riguardano varie parti fisiologia o la medicina Lindau, in Germania. estratti di articoli sulla biologia dal del corpo, tra cui i muscoli, il cervello incontreranno centinaia di giovani Come tributo all’incontro, nostro archivio, firmati da Nobel. e il sistema immunitario. www.lescienze.it Le Scienze 41 RAPPORTO LINDAU Fisiologia di Edgar Douglas Adrian NEUROSCIENZE Pubblicazione: settembre 1950 Premio Nobel: 1932 Scopo della fisiologia è descrivere I meccanismi cerebrali movimento. Si trova così che sia la gli eventi che avvengono della visione cellula gangliare della retina sia la nell’organismo e, nel farlo, aiutare di David H. Hubel e cellula del corpo genicolato hanno incidentalmente il medico. Ma quali Torsten N. Wiesel la migliore risposta a una fonte eventi, e in quali termini dovrebbe NEUPubblicazioneRO su «LeS Scienze»:C IEluminosaNZE più o meno circolare, di descriverli? Al riguardo, nell’ultimo novembre 1979 un certo diametro, e posta in una mezzo secolo c’è stato un Premio Nobel: 1981 certa zona del campo visivo. -

Volume A: Theory and User Information, Version 7.3 Part Number: RF-3001-07.3 Revision Date: August, 1998

MARC® Volume A Theory and User Information Version K7.3 Copyright 1998 MARC Analysis Research Corporation Printed in U. S. A. This notice shall be marked on any reproduction of this data, in whole or in part. MARC Analysis Research Corporation 260 Sheridan Avenue, Suite 309 Palo Alto, CA 94306 USA Phone: (650) 329-6800 FAX: (650) 323-5892 Document Title: MARC® Volume A: Theory and User Information, Version 7.3 Part Number: RF-3001-07.3 Revision Date: August, 1998 Proprietary Notice MARC Analysis Research Corporation reserves the right to make changes in specifications and other information contained in this document without prior notice. ALTHOUGH DUE CARE HAS BEEN TAKEN TO PRESENT ACCURATE INFORMATION, MARC ANALYSIS RESEARCH CORPORATION DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE CONTENTS OF THIS DOCUMENT (INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, WARRANTIES OR MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE) EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED. MARC ANALYSIS RESEARCH CORPORATION SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES RESULTING FROM ANY ERROR CONTAINED HEREIN, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, FOR ANY SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES ARISING OUT OF, OR IN CONNECTION WITH, THE USE OF THIS DOCUMENT. This software product and its documentation set are copyrighted and all rights are reserved by MARC Analysis Research Corporation. Usage of this product is only allowed under the terms set forth in the MARC Analysis Research Corporation License Agreement. Any reproduction or distribution of this document, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of MARC Analysis Research Corporation is prohibited. Restricted Rights Notice This computer software is commercial computer software submitted with “restricted rights.” Use, duplication, or disclosure by the government is subject to restrictions as set forth in subparagraph (c)(i)(ii) or the Rights in technical Data and Computer Software clause at DFARS 252.227-7013, NASA FAR Supp. -

Of Action of Anti-Erythrocyte Antibodies in a Murine Model of Immune Thrombocytopenia

Elucidating the Mechanism(s) of Action of Anti-Erythrocyte Antibodies in a Murine Model of Immune Thrombocytopenia by Ramsha Khan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology University of Toronto © Copyright by Ramsha Khan 2021 Elucidating the Mechanism(s) of Action of Anti-Erythrocyte Antibodies in a Murine Model of Immune Thrombocytopenia Ramsha Khan Doctor of Philosophy Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology University of Toronto 2021 Abstract Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune bleeding disorder that causes thrombocytopenia (decreased platelet numbers in the blood) primarily due to the presence of antiplatelet autoantibodies. Anti-D therapy (treatment with an antibody against the Rhesus-D factor on erythrocytes) has been proven to ameliorate ITP but as a human-derived product, it is limited in quantity and carries the potential risk of transferring emerging pathogens. Additionally, the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a black box warning for potentially serious adverse effects in ITP patients, including anemia, fever and/or chills. Therefore, there is incentive present for developing a safe and effective recombinant replacement that mimics the therapeutic activity of anti-D. Thus far, monoclonal anti-D antibodies have only had limited clinical success and better knowledge of its mechanism is required to accelerate the development of anti-D alternatives. This thesis documents studies that evaluated multiple anti- erythrocyte antibodies (as surrogates for anti-D) in murine models of ITP in order to provide insight regarding their mechanism(s) of action. Results indicate that adverse events such as anemia and temperature flux, which can be indicative of inflammatory activity, are not required for ITP amelioration; thus demonstrating that certain toxicities associated with anti-D therapy are independent of therapeutic activity and have the potential to be minimized when developing ii and/or screening synthetic alternatives. -

'Timely Topics in Medicine Original Articles • II1 ~Jm Ml,M~J~~ ~C

'Timely Topics in Medicine Page 1 of23 Original Articles Milestones in Transplantation: The Story so Far [06/12/2001] Thomas E. Starzl Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA .lntr9~!,!~tQryN91~ • Ih~I~<:I1.nl<:_~LCI1!lII~Jlg~ • II1~Sen:!ln~IT!'!IIlLIl9J;)9int~ • II1~Asc~m!~n<:Y.9fJ.mml,ln9.19gy • I.I1~J~ill.ingl1~m:~r~nt=~~~.~W~r ... ~~P-~rJm~n!~ • Im.ml.J.n9§.l.Jppr~s~j9.n.J.9r:Qrg.C1.. n... Ir~.n.~plC1ntC1Ji()lJ • I:CE!llJ:nr~<:t~~ Dru..Sl$ • Qrg~!LPr~$~ry~tl.9n • Imml.Jn919gi<:_$..<:r~~.nJng • ~IJ9g.r<!nAC::j:~p~<!n<:E!_~m:tAc::ql,J.irE!c:tT91E!.r<!n.c::~JnY9.ly~Jh~_S~m~_M.~c::h~ni.§.m$ • II1_~Jm ml,m~J~~_~c::ti.9n .. 1Q .. lnf~c::J1.()I,J$__ !I!11c::r:Q9rg!J.ni sl!l..$_j~... 111E! .. ~~m~_<!$I~.1 Against Allografts and Xenografts • C.9Ilc::II,J$i9f!.§ • 8~f.E!rE!nC::E!S Introductory Note The milestones in the following material were discussed at a historical consensus conference held at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to which 11 early workers in transplantation were invited: Leslie B. Brent (London), Roy Y. Caine (Cambridge, UK), Jean Dausset (Paris), Robert A. Good (St. Petersburg. USA), Joseph E. Murray (Boston). Norman E. Shumway (Palo Alto). Robert S. Schwartz (Boston), Thomas E. Starzl (Pittsburgh), Paul I. Terasaki (Los Angeles), E. Donnall Thomas (Seattle) and Jon J. van Rood (Leiden). -

History of Clinical Transplantation

World J. Surg. 2.:&.759-782.2000 DOl: 10.1007/s00268001012':& History of Clinical Transplantation Thomas E. Starzl, M.D., Ph.D. Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Falk Clinic. 4th Floor, 3601 Fifth Avenue. Pittsburgh. Pennsylvania 15213. USA Abstract. The emergence of transplantation has seen the development of to donor strain tissues was retained as the recipient animals grew increasingly potent immunosuppressive agents, progressively better to adult life, whereas normal reactivity evolved to third party methods of tissue and organ preservation. refinements in histocompati grafts and other kinds of antigens. bility matching. and numerous innovations in surgical techniques. Such efforts in combination ultimately made it possible to successfully engraft This was not the first demonstration that tolerance could be all of the organs and bone marrow cells in humans. At a more fundamen· deliberately produced. Analogous to the neonatal transplant tal level, however, the transplantation enterprise hinged on two seminal model. Traub [6] showed in 1936 that the lymphocytic choriomen turning points. The first was the recognition by Billingham. Brent, and Medawar in 1953 that it was possible to induce chimerism·associated igitis virus (LCMV) persisted after transplacental infection of the neonatal tolerance deliberately. This discovery escalated over the next 15 embryo from the mother or. alternatively. by injection into new years to the first successful bone marrow transplantations in humans in born mice. Howevt!r, when the mice were infected as adults. the 1968. The second turning point was the demonstration during the early virus was eliminated immunologicully. Similar observations had 1960s that canine and human organ allografts could self·induce tolerance been made in experimental tumor models.