Lessons from Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa and Rwanda Emily B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN SEARCH of Africa's Greatest Safaris

IN SEARCH of Africa's Greatest Safaris A S E R I E S O F L I F E C H A N G I N G J O U R N E Y S T H A T L E A V E A F R I C A ' S W I L D L I F E I N A B E T T E R P L A C E Who We Are Vayeni is owned and run by Luke & Suzanne Brown. Together they have built a formidable reputation for seeking out the finest safari experiences Africa can offer and combining these into cathartic experiences for the most judicious travellers. Luke and Suzanne also co- founded the Zambesia Conservation Alliance together with Luke's brother Robin. Through Zambesia their goal is to successfully assist Africa's increasingly threatened habitats and wildlife. Where We Take You East Africa Indian Ocean Islands Southern Africa Antarctica Comfort Between Destinations All journeys include a private jet between destinations & a dedicated, highly acclaimed African specialist guide throughout. CA AFRI EAST NDS ISLA CEAN AN O INDI ly p s e S e e E d d f i o R v a s U o . h r f e c S p o d i r A l t e r r a E c o a e e R n h w S t e S T d n S e i d y ' c v e T t e I la e c F p s e n I n s r R e n A l o u d c o n u J o re b atu ign S S OU T HE IND RN IA AF N R OC ICA ch of EA In Sear N ISL ICA AN T AFR DS EAS FRICA ERN A DS ECRETS UTH SLAN ZAMBESIA'S S SO EAN I N OC A INDIA CTIC NTAR A A vast & rich region of s, s, wildlife presided over by the o d of in r rgest African elephant herd 7 h pa s la ch R o le r T , e a on the planet. -

ARMING RWANDA the Arms Trade and Human Rights Abuses in the Rwandan War

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT January 1994 Vol. 6, Issue 1 ARMING RWANDA The Arms Trade and Human Rights Abuses in the Rwandan War Contents MapMap...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 IntroductionIntroduction....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Summary of Key Findings ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Summary of Recommendations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 I. Historical Background to the WarWar......................................................................................................................................7 The Banyarwanda and Uganda..............................................................................................................................................7 Rwanda and the Habyarimana Regime............................................................................................................................ 9 II. The Record on Human RightsRights..............................................................................................................................................11 -

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide:Lessom from the Rwanda Experience

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience March 1996 Published by: Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda Editor: David Millwood Cover illustrations: Kiure F. Msangi Graphic design: Designgrafik, Copenhagen Prepress: Dansk Klich‚, Copenhagen Printing: Strandberg Grafisk, Odense ISBN: 87-7265-335-3 (Synthesis Report) ISBN: 87-7265-331-0 (1. Historical Perspective: Some Explanatory Factors) ISBN: 87-7265-332-9 (2. Early Warning and Conflict Management) ISBN: 87-7265-333-7 (3. Humanitarian Aid and Effects) ISBN: 87-7265-334-5 (4. Rebuilding Post-War Rwanda) This publication may be reproduced for free distribution and may be quoted provided the source - Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda - is mentioned. The report is printed on G-print Matt, a wood-free, medium-coated paper. G-print is manufactured without the use of chlorine and marked with the Nordic Swan, licence-no. 304 022. 2 The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience Study 2 Early Warning and Conflict Management by Howard Adelman York University Toronto, Canada Astri Suhrke Chr. Michelsen Institute Bergen, Norway with contributions by Bruce Jones London School of Economics, U.K. Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda 3 Contents Preface 5 Executive Summary 8 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: The Festering Refugee Problem 17 Chapter 2: Civil War, Civil Violence and International Response 20 (1 October 1990 - 4 August -

Rwanda: Gender Politics and Women’S Rights I AFRS-3000 (3 Credits) Online Seminar: (July 13 Th to 31St)

Rwanda: Gender Politics and Women’s Rights I AFRS-3000 (3 credits) Online seminar: (July 13 th to 31st) This syllabus is representative of a typical semester. Because courses develop and change over time to take advantage of unique learning opportunities, actual course content varies from semester to semester. Course Description Rwanda is currently depicted as a model of quick growth and success in many areas including gender equality. In fact the country leads the world with women holding 61.3% of seats in the lower chamber of national legislature. In 2011, the Royal Commonwealth Society and Plan-UK, a British NGO, in its report published on March 14th, = ranked Rwanda as the 10th best country to be born a girl among 54 commonwealth countries. According to the same report, Rwanda was the 2nd country on the African continent after Seychelles. In 2020, Rwanda ranked 9th worldwide in the gender gap index between men and women in the four key areas of health, education, economy and politics (World Economic Forum Report on global gender gab index, 2020). This course is all about understanding what these apparently tremendous achievements mean in the everyday life of female citizens of Rwanda. Drawing on critical African women’s studies, contemporary feminist theories and theories of social change and social transformation, the course will examine the contemporary political, economic, legal, social as well as cultural reforms that have been influencing Rwanda’s gender politics and impacting women’s rights in all aspects of life. This is an online seminar that will be delivered from July 13th to 31st 2020. -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA

WHO HIVRESNET STEERING COMMITTEE MEETING, November 10–12, 2009, Geneva, Switzerland HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA Pr Belabbes Intercountry Support Team Central Africa COUNTRIES COVERED BY THE INTERCOUNTRY SUPPORT TEAM / CENTRAL AFRICA Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Equatorial Guinea Gabon Rwanda Sao Tome & Principe HIV PREVALENCE AMONG THE POPULATION Legend Generalized epidemic in 10 <1% countries /11 1-5% >5% Excepted Sao Tome& Principe nd HIV PREVALENCE AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN Legend <1% 1-5% >5% nd PATIENTS UNDER ART 2005-2008 70000 2005 2006 2007 2008 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 Angola Burundi Cameroon Congo Equatorial Gabon CAR DRC Rwanda Sao Tome Guinea Source of data Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. WHO, UNAIDS,UNICEF;September 2009. Training on HIVDR Protocols ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC CONGO EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON RWANDA SAO TOME&PRINCIPE Training on HIVDR Protocols Douala, Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 The opening ceremony Participants to the Training on HIVDR Protocols, Douala Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 ON SITE STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES OF THE TECHNICAL WORKING GROUPS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROVIDED TO DEVELOP HIVDR PROTOCOLS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA EARLY WARNING INDICATORS BURUNDI : EWI abstraction in 19 sites (October) using paper-based. -

Rwanda and the Politics of the Body

Rwanda and the Politics of the Body Erin Baines Working Paper No. 39, August 2003 Portions of the working paper will be published in Third World Quarterly, 24 (3) 2003 and are reprinted here with kind permission. With thanks to Natalie Oswin, Brian Job, Jennifer Hyndman, Susan Thomson, Suzy Hainsworth, Kate Woznow and Taylor Owen for comments and edits on earlier versions of this paper, and to the Social Sciences and Humanities Reseach Council. Recent Titles in the Working Paper Series No. 26 The Problem of Change in International Relations Theory, by K.J. Holsti, December 1998 No. 27 Asia and Nonproliferation After the Cold War: Issues, Challenges and Strategies, by J.D. Yuan, February 1999 No. 28 The Revolution in Military Affairs and Its Impact on Canada: The Challenge and the Consequences, by Andrew Richter, March 1999 No. 29 Law, Knowledge and National Interests in Trade Disputes: The Case of Softwood Lumber, by George Hoberg and Paul Howe, June 1999 No. 30 Geopolitical Change and Contemporary Security Studies: Contextualizing the Human Security Agenda, by Simon Dalby, April 2000 No. 31 Beyond the Linguistic Analogy: Norm and Action in International Politics, by Kai Alderson, May 2000 No. 32 The Changing Nature of International Institutions: The Case of Territoriality, by Kalevi J. Holsti, November 2000 No. 33 South Asian Nukes and Dilemmas of International Nonproliferation Regimes, by Haider K. Nizamani, December 2000 No. 34 Tipping the Balance: Theatre Missile Defence and the Evolving Security Relations in Northeast Asia, by Marc Lanteigne, January 2001 No. 35 Between War and Peace: Religion, Politics, and Human Rights in Early Cold War Canada, 1945-1950, by George Egerton, February 2001 No. -

Statement of Outcomes of the 6Th Africa Initiative Meeting 1St March 2019, Kigali, Rwanda

Statement of outcomes of the 6th Africa Initiative meeting 1st March 2019, Kigali, Rwanda 1. On 28 February – 1st March 2019, 68 delegates from 22 African countries and 11 Africa Initiative partners came together in Kigali, Rwanda, for the 6th meeting of the Africa Initiative (see annex 1). 2. The Africa Initiative was launched for a period of three years by the OECD hosted Global Forum in 2014 along with its African members and development partners (see annex 2). The Initiative aims to ensure that African countries can realise the full potential of progress made by the global community in implementing tax transparency and in international tax cooperation. With encouraging first results, its mandate was renewed for a further period of three years (2018-2020) in Yaoundé in November 2017. Countries participating in the Africa Initiative have committed to meeting specific and measurable targets in implementing and using the international tax transparency standards. 3. The delegates welcomed the attendance and support of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Central Africa Monetary and Economic Community (CEMAC), the East Africa Community (EAC), the Organisation for the harmonisation of business law in Africa (Organisation pour l’Harmonisation en Afrique du Droit des Affaires – OHADA) and the European Union for the first time at an Africa Initiative meeting. 4. Emphasising the increasing political focus on tackling illicit financial flows (IFFs) from Africa, delegates discussed how to convert political attention into tangible deliverables. They acknowledged that enhanced tax transparency is an important part of the solution to fighting tax evasion which in turn is a major component of IFFs. -

The Obama Administration and the Struggles to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

POLICY PAPER November 2016 THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION AUTHOR: AND THE STRUGGLE TO Charles J. Brown Leonard and Sophie Davis PREVENT ATROCITIES IN THE Genocide Prevention Fellow, January – June 2015. Brown is CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC currently Managing Director of Strategy for Humanity, LLC. DECEMBER 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2014 1 METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the product of research conducted while I was the Leonard and Sophie Davis Genocide Prevention Fellow at the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). It is based on a review of more than 3,500 publicly available documents, including material produced by the US and French governments, the United Nations, the African Union, and the Economic Community of Central African States; press stories; NGO reports; and the Twitter and Facebook accounts of key individuals. I also interviewed a number of current and former US government officials and NGO representatives involved in the US response to the crisis. Almost all interviewees spoke on background in order to encourage a frank discussion of the relevant issues. Their views do not necessarily represent those of the agencies or NGOs for whom they work or worked – or of the United States Government. Although I attempted to meet with as many of the key players as possible, several officials turned down or did not respond to interview requests. I would like to thank USHMM staff, including Cameron Hudson, Naomi Kikoler, Elizabeth White, Lawrence Woocher, and Daniel Solomon, for their encouragement, advice, and comments. Special thanks to Becky Spencer and Mary Mennel, who were kind enough to make a lakeside cabin available for a writing retreat. -

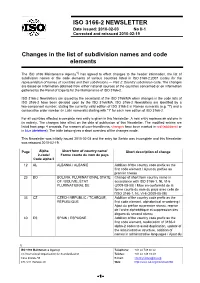

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Creating a Competitive Rwanda

Creating a Competitive Rwanda Professor Michael E. Porter Harvard Business School Kigali, Rwanda June 2007 This presentation draws on ideas from Professor Porter’s articles and books, in particular, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (The Free Press, 1990), “Building the Microeconomic Foundations of Competitiveness,” in The Global Competitiveness Report 2006 (World Economic Forum, 2006), “Clusters and the New Competitive Agenda for Companies and Governments” in On Competition (Harvard Business School Press, 1998), and ongoing research on clusters and competitiveness. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise - without the permission of Michael E. Porter. Further information on Professor Porter’s work and the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness is available at www.isc.hbs.edu Kenya CAON 2007 June-07.ppt 1 Copyright 2007 © Professor Michael E. Porter The Changing Nature of International Competition • Fewer barriers to trade and investment Drivers • Rapidly increasing stock and diffusion of knowledge • Competitiveness upgrading in many countries • Globalization of markets • Globalization of capital investment Market • Globalization of value chains reaction • Increasing knowledge and skill intensity of competition • Value migrating to the service component of the value chain • Improving competitiveness is increasingly essential to Rwanda’s prosperity Kenya CAON 2007 June-07.ppt 2 Copyright -

Country Codes ISO 3166

COUNTRY CODES - ISO 3166-1 ISO 3166-1 encoding list of the countries which are assigned official codes It is listed in alphabetical order by the country's English short name used by the ISO 3166/MA. Numeric English short name Alpha-2 code Alpha-3 code code Afghanistan AF AFG 4 Åland Islands AX ALA 248 Albania AL ALB 8 Algeria DZ DZA 12 American Samoa AS ASM 16 Andorra AD AND 20 Angola AO AGO 24 Anguilla AI AIA 660 Antarctica AQ ATA 10 Antigua and Barbuda AG ATG 28 Argentina AR ARG 32 Armenia AM ARM 51 Aruba AW ABW 533 Australia AU AUS 36 Austria AT AUT 40 Azerbaijan AZ AZE 31 Bahamas BS BHS 44 Bahrain BH BHR 48 Bangladesh BD BGD 50 Barbados BB BRB 52 Belarus BY BLR 112 Belgium BE BEL 56 Belize BZ BLZ 84 Benin BJ BEN 204 Bermuda BM BMU 60 Bhutan BT BTN 64 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) BO BOL 68 Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba BQ BES 535 Bosnia and Herzegovina BA BIH 70 Botswana BW BWA 72 Bouvet Island BV BVT 74 Brazil BR BRA 76 British Indian Ocean Territory IO IOT 86 Brunei Darussalam BN BRN 96 Bulgaria BG BGR 100 Burkina Faso BF BFA 854 Burundi BI BDI 108 Cabo Verde CV CPV 132 Cambodia KH KHM 116 Cameroon CM CMR 120 Canada CA CAN 124 1500 Don Mills Road, Suite 800 Toronto, Ontario M3B 3K4 Telephone: 416 510 8039 Toll Free: 1 800 567 7084 www.gs1ca.org Numeric English short name Alpha-2 code Alpha-3 code code Cayman Islands KY CYM 136 Central African Republic CF CAF 140 Chad TD TCD 148 Chile CL CHL 152 China CN CHN 156 Christmas Island CX CXR 162 Cocos (Keeling) Islands CC CCK 166 Colombia CO COL 170 Comoros KM COM 174 Congo CG COG