Franco and the Spanish Monarchy: a Discourse Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programa 337A Administración Del Patrimonio Histórico

PROGRAMA 337A ADMINISTRACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO NACIONAL 1. DESCRIPCIÓN Los objetivos y las actuaciones básicas del Consejo de Administración del Patrimonio Nacional para el ejercicio 2014, al igual que en los anteriores, vienen determinados por su propia Ley 23/1982, de 16 de junio, Reguladora del Patrimonio Nacional y por su Reglamento, aprobado por Real Decreto 496/1987, de 18 de marzo, modificado por los Reales Decretos 694/1989, de 16 de junio, 2208/1995, de 28 de diciembre, y 600/2011, de 29 de abril, que ha modificado la estructura orgánica del Organismo, en lo referente a las Unidades dependientes de la Gerencia. De acuerdo con lo previsto en el artículo primero de la Ley 23/1982, son fines del Consejo de Administración del Patrimonio Nacional la gestión y administración de los bienes y derechos del Patrimonio Nacional. En virtud del artículo segundo de dicha Ley, tienen la calificación jurídica de bienes del Patrimonio Nacional los de titularidad del Estado afectados al uso y servicio del Rey y de los miembros de la Familia Real para el ejercicio de la alta representación que la Constitución y las leyes les atribuyen. Además se integran en el citado Patrimonio los derechos y cargas de Patronato sobre las Fundaciones y Reales Patronatos a que se refiere la citada Ley. Y conforme prevé el artículo tercero de la Ley 23/1982, en cuanto sea compatible con la afectación de los bienes del Patrimonio Nacional, a la que se refiere el artículo anterior, el Consejo de Administración adoptará las medidas conducentes al uso de los mismos con fines culturales, científicos y docentes. -

Get £20 in Free Bets When You Stake £5

25/09/2018 DIVIDED: Experts and locals on digging up dictator Franco from the Valley of the Fallen in special Olive Press report from Madrid -… We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it. ACCEPT Read more / Saber mas GET £20 IN FREE BETS WHEN YOU STAKE £5 Close the Ad NEW CUSTOMERS ONLY || || ++1188 DIVIDED: EXPERTS AND LOCALS ON DIGGING UP DICTATOR FRANCO FROM THE VALLEY OF THE FALLEN IN SPECIAL OLIVE PRESS REPORT FROM MADRID Spain is a country still divided between those nostalgic for the Franco days and those who abhorred El Generalisimo By Heather Galloway - 22 Sep, 2018 @ 09:22 A QUEUE of trac a kilometre long snakes up to the gates of the Valley of the Fallen. As we inch forward, frying in the August heat, a large tattooed man draped in the Spanish ag steps out of the car in front and urinates on the road in direct view of my 18-year-old daughter. Valley of the Fallen, near Madrid Despite living in the shadow of Europe’s only remaining monument to a fascist leader – General Francisco Franco – I had not visited this striking but sinister place since 1993 when I was given short shrift for asking awkward questions. I expected the reception to be dierent 25 years on and you could call it that. The Valle de los Caidos, 50km from Madrid, is Franco’s OTT tribute to ‘the heroes and martyrs of the Crusade’ – a monolithic monument to those who ‘fell for God and for Spain in the Holy War against indels, Masons, Marxists, homosexuals and feminists’. -

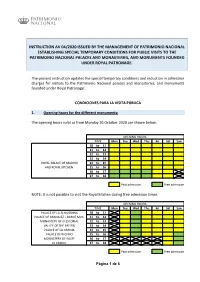

Instruction Av 04/2020 Issued by the Management Of

INSTRUCTION AV 04/2020 ISSUED BY THE MANAGEMENT OF PATRIMONIO NACIONAL ESTABLISHING SPECIAL TEMPORARY CONDITIONS FOR PUBLIC VISITS TO THE PATRIMONIO NACIONAL PALACES AND MONASTERIES, AND MONUMENTS FOUNDED UNDER ROYAL PATRONAGE. The present instruction updates the special temporary conditions and reduction in admission charges for visitors to the Patrimonio Nacional palaces and monasteries, and monuments founded under Royal Patronage: CONDICIONES PARA LA VISITA PÚBLICA 1. Opening hours for the different monuments: The opening hours valid as from Monday 26 October 2020 are shown below: OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 13 to 14 ROYAL PALACE OF MADRID 14 to 15 AND ROYAL KITCHEN 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission NOTE: It is not possible to visit the Royal Kitchen during free admission times. OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun PALACE OF LA ALMUDAINA 10 to 11 PALACE OF ARANJUEZ + BARGE MUS. 11 to 12 MONASTERY OF El ESCORIAL 12 to 13 VALLEY OF THE FALLEN 13 to 14 PALACE OF LA GRANJA 14 to 15 PALACE OF RIOFRIO 15 to 16 MONASTERY OF YUSTE 16 to 17 EL PARDO 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission Página 1 de 6 OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10:00 to 10:30 10:30 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 CONVENT OF SANTA MARIA LA REAL HUELGAS 13 to 14 14 to 15 CONVENT OF SANTA CLARA TORDESILLAS 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 18 to 18:30 Paid admission Free admission The Casas del Príncipe (at El Pardo and El Escorial), Casa del Infante (at El Escorial) and Casa del Labrador (at Aranjuez) will not be open. -

Museológica: Tendencias E Diccionario Deldibujoylaestampa Instrumentos Léxicosdeinterés,Comoel Definitiva

ARTE GRÁFICO Y LENGUAJE1 Javier Blas José Manuel Matilla Calcografía Nacional Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando tendencias l empleo de una terminología adecuada relativa al arte gráfico no es una E cuestión irrelevante para el profesional de museos. Precisar el uso de las palabras que integran el vocabulario técnico de la estampa, es decir, atender a su valor semántico, no es sólo una necesidad sino también una exigencia por sus implicaciones en la valoración social museológica: del grabado y procedimientos afines. El debate sobre el vocabulario del arte gráfico sigue abierto, ya que la normalización lingüística en este campo del conocimiento aún no ha sido presentada de manera definitiva. No obstante, hoy se dispone de instrumentos léxicos de interés, como el Diccionario del dibujo y la estampa2, cuyos Lámina. Entintado de la lámina planteamientos ofrecen una línea argumental Francisco de Goya, Volaverunt razonada y son la expresión de una tendencia en el uso de la terminología avalada por las fuentes históricas. Al margen del modelo que propone ese repertorio, cualquier otra alter- nativa de normalización podría ser aceptable. Lo que no resulta admisible es la dispersión de criterios para la definición de idénticos procesos y productos gráficos. 122 museológica. tendencias El uso indebido del lenguaje ha Precisar el uso de las Directamente relacionada con la perpetuado algunas conductas poco citada jerarquía de los medios afortunadas, entre ellas la igualación palabras que integran gráficos se encuentra una cuarta del campo semántico en significantes el vocavulario técnico constatación: el menosprecio genera- de muy distinta procedencia histórica lizado hacia las técnicas introducidas y etimológica. -

Rural Tourism in Spain, from Fordism to Post-Fordism

PART VI ALTERNATIVE TOURISM RURAL TOURISM IN SPAIN, FROM FORDISM TO POST-FORDISM Lluís Garay Economics and Business Department, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Barcelona, Spain Gemma Cànoves Geography Department, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Barcelona, Spain and Juan Antonio Duro Economics Department, Universitat Rovirai Virgili Tarragona, Spain ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is twofold: from an empirical perspective, to demonstrate the qualitative importance of rural tourism in the recent development of Spanish tourism and its quantitative importance for other sectors such as agriculture; and from a conceptual perspective, to demonstrate the validity of the combination of two theoretical approaches. On the one hand, the Tourism Area Life Cycle, the most commonly used for this purpose since its publication thirty years ago and, on the other hand, the Regulation Theory, aimed at explaining the restructuring processes between different stages in specific sectors or in the whole economy. Key Words: Rural Tourism, Life Cycle, Regulation Theory, Restructuring, Fordism, Post-fordism. INTRODUCTION The tourism sector is undoubtedly one of the main sources of income of the Spanish economy. The country is currently the second favourite international destination in the world and the sector generates about 12% of the country’s total income and jobs (INE, 2010). Historically, the sector was one of the main engines that brought about the recovery of the Spanish economy in the last fifty years and has been frequently identified with the mass model of sun and sea tourism, but the country has a vast potential to offer in other typologies, as proved in recent years with the explosive growth of urban tourism. -

The Valley of the Fallen in Spain. Between National Catholicism and the Commodification of Memory

CzasKultury/English 4/2017 The Valley of the Fallen in Spain. Between National Catholicism and the Commodification of Memory Maja Biernacka Thanatourism is a portmanteau derived from the word “tourism” and the Greek term tanatos. The latter means death, although when capitalized, it indicates the god of death in Greek mythology. The concept refers to the act of visiting – individually or as a group – locations that have witnessed natural disasters, battles with staggering casu- alties, or acts of genocide (such as concentration camps, sites of mass shootings, or memorials devoted to these acts). Moreover, thanatourism takes a form of group ex- cursions organized under the theme of death, and comes with all the usual services – transportation, accommoda- tions, licensed tour guides, souvenir sales, and so forth. 18 Maja Biernacka, The Valley of the Fallen in Spain Polish scholarship adopted the term1 following its English equivalent thanatourism,2 which literally translates to “death tourism.”3 An adjacent concept is “dark tourism”4 (in Polish, mroczna turystyka),5 which expands the object of interest from death to all phenomena falling under the banner of “dark” or “morbid.” Other related terms appear as well, such as “grief tourism,” which serve to modify the scope or character of such activity. It seems relevant to emphasize that these notions may be incorporated into critical methodologies in the social sciences, due to their demystifying nature. I am refer- ring specifically to taking advantage of the value of sites bound up with death, suffering, human tragedy and the like, which play a crucial role in the collective memory of a nation, ethnic or religious group, or any other kind of imagined community – to use Benedict Anderson’s term6 – and putting a price on them for touristic purpos- es. -

BROCHURE-ARRE-2011-UK:Mise En Page 1

Discovering European Heritage in Royal Residences Association of European Royal Residences Contents 3 The Association of European Royal Residences 4 National Estate of Chambord, France 5 Coudenberg - Former Palace of Brussels, Belgium 6 Wilanow Palace Museum, Poland 7 Palaces of Versailles and the Trianon, France 8 Schönbrunn Palace, Austria 9 Patrimonio Nacional, Spain 10 Royal Palace of Gödöllo”, Hungary 11 Royal Residences of Turin and of the Piedmont, Italy 12 Mafra National Palace, Portugal 13 Hampton Court Palace, United Kingdom 14 Peterhof Museum, Russia 15 Royal Palace of Caserta, Italy 16 Prussian Palaces and Gardens of Berlin-Brandenburg, Germany 17 Royal Palace of Stockholm, Sweden 18 Rosenborg Castle, Denmark 19 Het Loo Palace, Netherlands Cover: Chambord Castle. North facade © LSD ● F. Lorent, View from the park of the ruins of the former Court of Brussels, watercolour, 18th century © Brussels, Maison du Roi - Brussels City Museums ● Wilanow Palace Museum ● Palace of Versailles. South flowerbed © château de Versailles-C. Milet ● The central section of the palace showing the perron leading up to the Great Gallery, with the Gloriette in the background © Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H., Vienna ● Real Sitio de La Granja de San Ildefonso © Patrimonio Nacional ● View from the garden © Gödöllo “i Királyi Kastély ● The Margaria © Racconigi ● Venaria Reale. View of the Palace © Venaria Reale ● Mafra National Palace. Photo S. Medeiros © Palacio de Mafra ● Kew Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● White Tower, Tower of London © Historic Royal Palaces ● Kensington Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Banqueting House © Historic Royal Palaces ● Hampton Court Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Grand Palace and Grand Cascade © Peterhof Museum ● Caserta – Royal Palace – Great staircase of honour © Soprintendenza BAPSAE. -

IBERIAN HOLIDAY MADRID, TOLEDO and SEGOVIA Monday, December 28, 2015 Through Sunday, January 3, 2016

AN IBERIAN HOLIDAY A NEW YEAR’S CELEBRATION IN MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA* Monday, December 28, 2015 through Sunday, January 3, 2016 *Itinerary subject to change $ 3,600.00per person INCLUDING AIR $2,400.00 per person LAND ONLY $450.00 additional for SINGLE SUPPLEMENT Join us on our ANNUAL NEW YEAR’S TRIP takes you to SUNNY SPAIN AND THREE OF ITS MOST INTERESTING CITIES – MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA. Our custom itinerary showcases a variety of museums, delicious dining experiences and fascinating sites from the ancient to the modern that come together on this wonderful Iberian Holiday. DAY 1 - MONDAY, DECEMBER 28 NEWARK Board United Airlines Flight #964 departing Newark Liberty Airport at 8:20pm for our NON-STOP trip to Madrid DAY 2 - TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29 MADRID (L/D) Arrive at Madrid’s Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport at 9:45am, gather our luggage and meet our coach and guide. After lunch, take a panoramic city tour where you will see many of Madrid’s beautiful Plazas, Monuments, Shopping Streets and Fountains. Visit some of the city’s different districts including the typical "castizo" (Castilian) quarter of "la Moreria." Check into the beautiful and centrally located Four Star Hotel NH Collection Madrid Paseo del Prado at 3:00 Relax for the rest of the afternoon. Dine with your fellow travelers at a festive Welcome Dinner DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 30 MADRID (B/L/D) Meet our local guide for a short walk to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Take a guided stroll down the history of European painting, from its beginning in the 13th century to the close of the 20th century by visiting works by Van Eyck, Dürer, Caravaggio, Rubens, Frans Hals, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Kirchner, Mondrian, Klee, Hopper, Rauschenberg .. -

Map of La Rioja Haro Wine Festival

TRAVEL AROUND SPAIN SPAIN Contents Introduction.................................................................6 General information......................................................7 Transports.................................................................10 Accommodation..........................................................13 Food.........................................................................15 Culture......................................................................16 Region by region and places to visit..............................18 Andalusia........................................................19 Aragon............................................................22 Asturias..........................................................25 Balearic Islands...............................................28 Basque Country................................................31 Canary Islands.................................................34 Cantabria........................................................37 Castille-La Mancha...........................................40 Castille and León.............................................43 Catalonia........................................................46 Ceuta.............................................................49 Extremadura....................................................52 Galicia............................................................55 La Rioja..........................................................58 Madrid............................................................61 -

THE PROMOTION of TOURISM in SPAIN from Stereotype to Brand Image

THE PROMOTION OF TOURISM IN SPAIN From stereotype to brand image FERNANDO LLORENS BAHENA UNIVERSITY OF SALENTO 1. Introduction When we speak of stereotypes, few of us are aware that that the word originally referred to a duplicate impression of a lead stamp, used in typography for printing an image, symbol or letter. These stamps could be transferred from place to place, and it is this feature that gave rise to the current metaphorical meaning of stereotype as a set of commonly held beliefs about specific social groups that remain unchanged in time and space. Etymologically, the term stereotype derives from the Greek words stereos, ‘firm, solid’ and typos, ‘impression’. The earliest record we have of its use outside the field of typography was in psychiatry, in reference to pathological behaviours characterised by the obsessive repetition of words and gestures. The first use of the term in the context of social sciences was by the journalist Walter Lippmann in his 1922 work “Public Opinion”. He argued that people’s comprehension of external reality is not direct but comes about as a result of “the pictures in their heads”, the creation of which is heavily influenced by the press, which in Lippmann’s time was rapidly transforming itself into the mass media that we know today. Lippmann believed that these mental images were often rigid oversimplifications of reality, emphasising some aspects while ignoring others. This is because the human mind is not capable of understanding and analysing the extreme complexity of the modern world. Stereotypes are, furthermore, a ‘group’ concept. We cannot speak therefore of ‘private’ stereotypes because they are based on collective uniformity of content. -

Tourism Satellite Account of Spain. Year 2019

11 December 2020 Spanish Tourism Satellite. Statistical review 2019 2016–2019 Series The contribution from tourism reached 154,487 million euros in 2019, representing 12.4% of the GDP Tourism-related industries generated 2.72 million jobs, or 12.9% of total employment. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contribution associated with tourism, measured using total tourist demand, reached 154,487 million euros in 2019. This figure represented 12.4% of GDP, three tenths more than in 2018. Since 2015, the contribution of tourism to GDP has increased by 1.3 points, from 11.1% to 12.4%. In turn, employment in tourism-related industries reached 2.72 million jobs. This represented 12.9% of total employment in the economy, 0.1% less than in 2018. The contribution of tourism-related jobs has increased by 0.8 points since 2015, from 12.1% to 12.9% of total employment in the economy. Contribution of tourism to GDP and employment Percentage 12.6 13.0 12.9 12.1 12.3 12.1 12.1 12.4 11.3 11.1 2015 2016 2017 2018 (P) 2019 (A) Contribution of tourism to GDP Employment in characteristic branches of activity (% total employment) (P): Provisional estimate, (A): Preview estimate Spanish Tourism Satellite. Statistical review 2019-2016–2019 Series (1 /4) In 2019, the component with the greatest contribution to domestic tourism consumption the inbound tourism expenditure, with 54.7% of the total. Contribution of inbound tourist consumption to to domestic tourism consumption Percentage 54.4 54.0 54.1 54.7 2016 2017 2018 (P) 2019 (A) (P): Provisional estimate, (A): Preview estimate Total tourism demand increased by 3.3%, in terms of volume, in 2019. -

Culinary Tourists in the Spanish Region of Extremadura, Spain

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics López-Guzmán, Tomás; Di-Clemente, Elide; Hernández Mogollón, José Manuel Article Culinary tourists in the Spanish region of Extremadura, Spain Wine Economics and Policy Provided in Cooperation with: UniCeSV - Centro Universitario di Ricerca per lo Sviluppo Competitivo del Settore Vitivinicolo, University of Florence Suggested Citation: López-Guzmán, Tomás; Di-Clemente, Elide; Hernández Mogollón, José Manuel (2014) : Culinary tourists in the Spanish region of Extremadura, Spain, Wine Economics and Policy, ISSN 2212-9774, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 3, Iss. 1, pp. 10-18, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2014.02.002 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194480 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.