Emma Lou Diemer's Solo Piano Works Through 2010: a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOLO KEYBOARD MIXED COLLECTIONS Collections Containing Works by Various Composers ______50092970 32 Sonatinas and Rondos, Vol

97144 Kybd 212-246 8/29/05 8:33 AM Page 212 212 SOLO KEYBOARD MIXED COLLECTIONS Collections containing works by various composers ______50092970 32 Sonatinas and Rondos, Vol. 2 Ricordi RER1455 ........................................................$17.95 ______50331300 36 Twentieth Century Pieces ____50327800 1st Pedal Studies for Piano: Progressive Exercises Schirmer ED2734 ........................................................$14.95 and Pieces (Diller/Quaile) Schirmer ED1732 ..........................................................$9.95 ______50332880 1st Solo Book for Piano Revised (Diller/Quaile) Schirmer ED2956 ..........................................................$6.95 ______50333260 2nd Solo Book for Piano Revised (Diller/Quaile) Schirmer ED3014 ..........................................................$5.95 ______50326980 3rd Solo Book for Piano (Diller/Quaile) Schirmer ED1456 ..........................................................$8.95 ______50326990 4th Solo Book for Piano (Diller/Quaile) Schirmer ED1457 ..........................................................$8.95 ______50235990 6 Piano Sonatinas ______50327580 51 Pieces from the Modern Repertoire by Belgian Composers Vol. 1 (Huybregts) Schirmer ED1672 ........................................................$16.95 Contents: Jean Absil: Sonatina (Suite Pastorale) Op. 37; Victor De Bo: Sonatina in D; George Longue: Sonatina in ______50328500 57 Pieces Children Like to Play D, Op. 32; Armand Longue: Sonatina in D minor, Op. 34; Schirmer ED2050 ........................................................$12.95 -

Three Sonatas for Piano by Emma Lou Diemer Chin-Ming Michelle Lin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Three sonatas for piano by Emma Lou Diemer Chin-Ming Michelle Lin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lin, Chin-Ming Michelle, "Three sonatas for piano by Emma Lou Diemer" (2007). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1660. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1660 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THREE SONATAS FOR PIANO BY EMMA LOU DIEMER A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Chin-Ming Lin B.F.A., Tunghai University, Taiwan, 2000 M.M., Carnegie Mellon University, 2003 December, 2007 To my parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the members of my committee throughout my doctoral studies and during the writing of this paper at Louisiana State University. I am very thankful for my previous piano professor Dr. Jennifer Hayghe for her tremendous guidance and piano teaching in first two years of my doctoral residency; a special thanks to my major professor Mr. Gregory Sioles for his enthusiastic and brilliant teaching in piano and his dedication in revising this written document and helping me prepare for my lecture recital; Professor Michael Gurt for contributing his insightful expertise and musicianship; Dr. -

RICHARD DE GUIDE Alain Van Kerckhoven

RICHARD DE GUIDE Alain Van Kerckhoven de GUIDE, Richard, compositeur et pédagogue, né à Basècles en Hainaut le 1er mars 1909, décédé à Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (Bruxelles) le 12 janvier 1962. Au sortir de ses humanités accomplies à l'Athénée d'Ath, Richard de Guide se lança simultanément dans des études de chimie à l'Université Libre de Bruxelles et dans la composition musicale. Il devint ingénieur chimiste mais l'enseignement de maîtres tels que Paul Gilson, Karel Candael et surtout Jean Absil orienta sa carrière vers la musique et son destin vers la composition. Il rejoint en 1938 les services musicaux de l'Institut National de Radiodiffusion (I.N.R.) où il prit part durant la guerre à des actes de sabotage qui lui valurent d'être fait prisonnier par l'occupant en 1944 et incarcéré à Huy jusqu'en 1945. Cette expérience donnera quelques années plus tard naissance à l'un de ses chefs-d'oeuvre. L'année suivante, Richard de Guide devient directeur de l'Académie de Musique de Woluwe-Saint-Pierre où il enseigne le piano et l'histoire de la musique. Il sera aussi professeur d'harmonie au Conservatoire royal de Liège de 1950 à 1953, et professeur de composition au Conservatoire royal de Mons de 1961 jusqu'à sa mort survenue prématurément l'année suivante. L'écriture critique l'accompagnera tout au long de sa carrière : Richard de Guide fut collaborateur musical de l'hebdomadaire « Les Beaux-Arts » de 1946 à 1951, critique musical de « La Nouvelle Gazette de Bruxelles » de 1946 à 1958 et correspondant de nombreuses publications étrangères : « Disques », « Musica », « Radio-Magazine » et « La Revue Musicale Suisse ». -

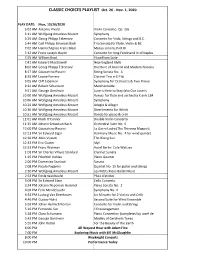

Oct 26 to Nov 1.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Oct. 26 - Nov. 1, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 10/26/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto, Op. 3/6 6:11 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 6:29 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Viola, Strings and B.C. 6:44 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Trio Sonata for Flute, Violin & BC 7:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 7:12 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto for King Ferdinand IV of Naples 7:29 AM William Byrd Fitzwilliam Suite 7:41 AM Edward MacDowell New England Idylls 8:02 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture of Ancient and Modern Nations 8:17 AM Gioacchino Rossini String Sonata No. 5 8:33 AM Louise Farrenc Clarinet Trio in E-Flat 9:05 AM Cliff Eidelman Symphony for Orchestra & Two PIanos 9:34 AM Robert Schumann Märchenbilder 9:51 AM George Gershwin Love is Here to Stay (aka Our Love is 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for flute and orchestra K anh.184 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 10:24 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Adagio & Allegro 10:36 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 10:51 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Rondo for piano & orch 11:01 AM Mark O'Connor Double Violin Concerto 11:35 AM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 4 12:00 PM Gioacchino Rossini La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie): 12:13 PM Sir Edward Elgar Harmony Music No. 4 for wind quintet 12:26 PM Allen Vizzutti The Rising Sun 12:43 PM Eric Coates Idyll 12:51 PM Franz Waxman Hotel Berlin: Cafe Waltzes 1:01 PM Sir Charles Villiers Stanford Clarinet Sonata 1:25 PM Friedrich Kuhlau Piano Quartet 2:00 PM Domenico Scarlatti Sonata 2:08 PM Nicolo Paganini Quartet No. -

BENELUX and SWISS SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

BENELUX AND SWISS SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman JEAN ABSIL (1893-1974) BELGIUM Born in Bonsecours, Hainaut. After organ studies in his home town, he attended classes at the Royal Music Conservatory of Brussels where his orchestration and composition teacher was Paul Gilson. He also took some private lessons from Florent Schmitt. In addition to composing, he had a distinguished academic career with posts at the Royal Music Conservatory of Brussels and at the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel and as the long-time director of the Music Academy in Etterbeek that was renamed to honor him. He composed an enormous amount of music that encompasses all genres. His orchestral output is centered on his 5 Symphonies, the unrecorded ones are as follows: No. 1 in D minor, Op. 1 (1920), No. 3, Op. 57 (1943), No. 4, Op. 142 (1969) and No. 5, Op. 148 (1970). Among his other numerous orchestral works are 3 Piano Concertos, 2 Violin Concertos, Viola Concerto. "La mort de Tintagiles" and 7 Rhapsodies. Symphony No. 2, Op. 25 (1936) René Defossez/Belgian National Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 1, Andante and Serenade in 5 Movements) CYPRÈS (MUSIQUE EN WALLONIE) CYP 3602 (1996) (original LP release: DECCA 173.290) (1958) RAFFAELE D'ALESSANDRO (1911-1959) SWITZERLAND Born in St. Gallen. After some early musical training, he studied in Paris under the tutelage of Marcel Dupré (organ), Paul Roës (piano) and Nadia Boulanger (counterpoint). He eventually gave up composing in order to earn a living as an organist. -

Nbr 227 1972

KRAB PROGRAM GUI DE NUMBE R TWO HUNDRED AND TWENTY SEVEN Publ ished by the J ack Straw Memorial Foundati on, a non- profit, tax- exemp t ~ public or ganizat i on s olely designed to oper ate non- commercial, listener suppor ted radio s t at ions , of which KRAB is one, and KBOO (Portland) t he other. Th i s progr am guide, containing program listings for t he month of June , 1 972 ~ is not s o l d ~ it is gi ven, f ree of charge, to t he subs cr i bers and supporters of KRAB . We emph asize the fact that those who subs cribe aren't paying f or the progr am guide ~ but paying for KRAB o Subs cription rates to KRAB are $25 . 00 average yearly, $15 . 00 minimum yearly (for students , reti red people, and unemployed people) J or $5.00 for four months. Your contri bution or subscription is tax-deductible; checks and money orders should be made out to the Jack Straw Memori al Foundation. KRAB PM Studl o~ 90 29 Roosevelt Way N. E. Off ice : 1400 Harvard Avenue Se at t l e, WaD 98115 Seattle, Wa D 9812 2 Studi o : LA 2-5111 Office ~ EA 5-5110 and EA 5-5111 20.000 watts e .r.p . 107.7 on your dial If you 're moving please let us know so we can change your address card i n our file ; otherwise the post office may thr ow out your program guides r ather t han forwar d them. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Repertoire for Alto

AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED REPERTOIRE FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO FOR DE VELOPING COLLEGE-LEVEL ALTO SAXOPHONISTS, WITH AN ANALYSIS OF YVON BOURREL’S SONATE POUR ALTO SAXOPHONE ET PIANO Scott D. Kallestad, B.S., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2005 APPROVED: Eric M. Nestler, Major Professor Eugene M. Corporon, Minor Professor Darhyl S. Ramsey, Committee Member Graham H. Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kallestad, Scott D., An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Repertoire for Alto Saxophone and Piano for Developing College-Level Alto Saxophonists, with an Analysis of Yvon Bourrel’s Sonate Pour Alto Saxophone Et Piano. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2005, 95 pp., 25 Figures, references, 82 titles. In this study the author addresses the problem of finding quality repertoire for young college-level saxophonists. By examining graded repertoire lists from a variety of college and university saxophone instructors, the author has compiled a list of 180 works for alto saxophone and piano. Twenty-four well-known works of a difficulty-level appropriate for freshman and sophomore players are identified and annotated. Each annotation consists of bibliographical information, a biographical sketch of the composer, a difficulty rating of eight elements of performance, a discussion of performance considerations, and a bibliography of available recordings. The eight elements of performance included in the difficulty rating are: Meter, key signatures, tempo, note-values, rhythm, articulation, range, and dynamic levels. -

A Selection Box from Rachel Talitman's Harp &

A Selection Box from Rachel Talitman's Harp & Co. A survey by Rob Barnett Harp supremo Rachel Talitman has laboured for her instrument and repertoire and has done so with unwavering conviction. That this has borne artistic achievement as a musician is not taken for granted. Talitman has been the driving force through which her label Harp & Co has placed so much before audiences. MusicWeb International has already reviewed various of her discs (Cras; Hasselmanns; Cardon; Lefèvre; Damase; In the Light of Ravel; Bochsa) but the time has arrived to give an overview of a selection of her discs. Her efforts have harvested many rare, and some not so rare, composers and have Ms Talitman as the player hub around which she has drawn together a 'family' of elite instrumentalists. These musicians pride themselves on technical proficiency and fidelity to emotional essence. Although she has the occasional solo, Talitman's role is perhaps grievously underestimated as the titles of so many of these compositions relegate her position to the end of a long list of instrumentalists as "and harp". Four of the nine discs I have listened to are anthologies and five are devoted to a single composer. There's a struggle to find a negative side to these discs but despite their merits there is a tendency to opt for short playing times. In addition, the label is reticent about dates of works and recording session minutiae. That said, these seem, going by the close-up yet uncloying results, to date from the 2000s and 2010s. Ms Talitman's profile can be scanned as follows: born in Tel-Aviv and graduate of the city's university. -

Queen Elisabeth Competition 1937-2019 Violin Piano Cello Voice Composition

QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 1937-2019 VIOLIN PIANO CELLO VOICE COMPOSITION VIOLIN 1937 [EUGENE YSAŸE COMPETITION] Laureates Jury 1. David OISTRAKH [Former USSR] Victor BUFFIN DE CHOSAL [president] 2. Ricardo ODNOPOSOFF [Austria] Mathieu CRICKBOOM 3. Elisabeth GUILELS [Former USSR] Marcel DARRIEUX 4. Boris GOLDSTEIN [Former USSR] André DE RIBEAUPIERRE 5. Marina KOZOLUPOVA [Former USSR] Désiré DEFAUW 6. Mikhail FICHTENGOLZ [Former USSR] Oscar ESPLA 7. Lola BOBESCO [Romania] Indrich FELD 8. Paul MAKHANOVITZKI [Sweden] Carl FLESCH 9. Robert VIROVAY [Hungary] André GERTLER 10. Angel REYES [Cuba] Jeno HUBAY 11. Ricardo BRENGOLA [Italy] Abraham JAMPOLSKY 12. Jean CHAMPEIL [France] Wachtald KOCHANSKY George KULENKAMPFF Arthur LEMBA Franz MAIRECKER Arrigo SERATO Joseph SZIGETI Jacques THIBAUD Gabry YSAŸE ZIMMERMANN Prelude concert for the finals [21.03.1937] Grand Orchestre Symphonique de l’I.N.R., cond. Franz ANDRÉ Alfred DUBOIS Orchestra for the finals [30-31.03-01.04.1937] Grand Orchestre Symphonique de l’I.N.R., cond. Franz ANDRE PIANO 1938 [EUGENE YSAŸE COMPETITION] Laureates Jury 1. Emil GUILELS [Former USSR] Victor BUFFIN DE CHOSAL [president] 2. Mary JOHNSTONE [United Kingdom] Vytautas BACEVICIUS 3. Jakob FLIER [Former USSR] Arthur BLISS 4. Lance DOSSOR [United Kingdom] Robert CASADESUS 5. Nivea MARINO-BELLINI [Uruguay] Marcel CIAMPI 6. Robert RIEFLING [Norway] Jean DOYEN 7. Arturo BENEDETTI-MICHELANGELI [Italy] Samuel FEINBERG 8. André DUMORTIER [Belgium] Paul FRENKEL 9. Rose SCHMIDT [Germany] Emile FREY 10. Monique YVER DE LA BRUCHOLLERIE -

Junwen Jia, Soprano and Alto Saxophone Junwen Jia

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-3-2013 Senior Recital: Junwen Jia, soprano and alto saxophone Junwen Jia Cayuga Saxophone Quartet Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Jia, Junwen and Quartet, Cayuga Saxophone, "Senior Recital: Junwen Jia, soprano and alto saxophone" (2013). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2311. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2311 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Senior Recital: Junwen Jia, soprano and alto saxophone Kathy Hansen, piano Cayuga Saxophone Quartet: Yuyang Zhang, alto saxophone Brian Dill, tenor saxophone Ian Herbon, baritone saxophone Ford Hall Sunday November 3rd, 2013 7:00 pm Program The Sonata for oboe and piano(1962) Francis Poulenc I. Elégie (Paisiblement, Sans Presser) (1899-1963) II. Scherzo (Très animé) III. Déploration (Très calme) Tableaux de Provence(1957) Paule Maurice I. Farandoulo di chatouno (Farandole of young (1910-1967) women) II. Cansoun per ma mio (Song for my love/mother) III. La boumiano (The Bohemian woman, or The Gypsy) IV. Dis alyscamps l'amo souspire (A Sigh of the soul for the Alyscamps) V. Lou cabridan (The Bumblebee) Concertino da Camera(1935) Jacques Ibert I. Allegro con moto (1890-1962) II. Larghetto – Animato Molto Suite sur des themes populaires roumains, op. Jean Absil 90(1956) (1893-1974) I. Allegro vivace II. Andante con moto III. -

Concerts 1979 – 2019

Concerts 1979 – 2019 2019 Saturday, 23 November 2019, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 40th anniversary of the Brussels Choral Society Leonard Bernstein: Chichester Psalms Igor Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms Carl Orff: Carmina Burana Soloists: Julie Gebhart, soprano Teun Michiels, tenor Michael Adair, baritone Julia O’Connor, soprano (A member of La Monnaie Children’s and Youth Choir) The International School of Brussels VoiceWorks Choir Members of Les Petits Chantres de Saint-François Ensemble Orchestral de Bruxelles Eric Delson, conductor Saturday, 18 May 2019, N.D. des Grâces, Chant d’Oiseau, Brussels Made in Italy Carlo Gesualo - Asciugate i begli occhi -T’amo, mia vita! Salomone Rossi - Psalm 124 - Psalm 128 Claudio Monteverdi - Hor ch’el Ciel e la Terra Giovanni Pierluigi - Da Palestrina - Sicut cervus - Missa Brevis Soloists: Carina Miruna Adam, violin Silva Bazantova, violin Koen Berger, cello Gabriel Diaconu, harpsichord Eric Delson, conductor Saturday, 16 February 2019, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels A Concert for Peace Guillaume Lekeu: Adagio pour Quatuor d’Orchestre Max Bruch: Violin Concerto No 1 in G minor, Op. 26 Arnold Schönberg: Friede auf Erden, Op. 13 Ralph Vaughan Williams: Dona Nobis Pacem Soloists: Laeticia Cellura, violin Iris Hendrickx, soprano Matthew Zadow, bass Brussels Philharmonic Orchestra David Navarro Turres, conductor Page 1 2018 Saturday, 17 November 2018, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels Giuseppe Verdi: Missa da Requiem Soloists: Agnes Selma Weiland, soprano Ève-Maud Hubeaux, mezzo-soprano Alex Kim, tenor Raimund Nolte, bass Philharmonisher Chor der Stadt Bonn Ensemble Orchestral de Bruxelles Eric Delson, conductor Friday, 9 November 2018, Opernhaus, Bonn (Germany) Giuseppe Verdi: Missa da Requiem Soloists: Adina Aaron, soprano Julia Gertseva, mezzo-soprano Eduardo Aladrén, teno Albert Pesendorfer, bass Philharmonisher Chor der Stadt Bonn Beethoven Orchester Bonn Dirk Kaftan, conductor Saturday, 16 June 2018, N.D. -

CHAMBER MUSIC for the E-FLAT CLARINET by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw ---A Document Submitted to the Facult

Chamber Music for the E-Flat Clarinet Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Redshaw, Jacqueline Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 01:51:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194436 CHAMBER MUSIC FOR THE E-FLAT CLARINET by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw ------------------- A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 7 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw entitled Chamber Music for the E-Flat Clarinet and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 Jerry Kirkbride _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 William Dietz _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 Gregg I. Hanson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s