Primitiae (IA Primitiae00alexiala).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts, Literary & History Trail

Arts, Literary & History Trail - FRESHWATER - KS4 Alfred, Lord Tennyson Poet Laureate Resident at Farringford House, Freshwater Tennyson was born in Lincolnshire in 1809 and attended Trinity College, Cambridge in 1827 where he received The Chancellor’s Gold Medal (a prestigious award given for poetry) in 1829. His frst solo collection of poems were published soon after. Poetry wriritng was important to Victorians as there was no recorded music at this time. When Tennyson’s poem ‘Maud’ (written in 1854-55) became a frm favourite with British Society, Alfred Lord Tennyson was able to buy Farringford House (now a hotel), on the Isle of Wight, which he initially rented with his wife from 1853. In 1850, he was made Poet Laureate and he held this post for forty years. Heralded as one of the greatest poets in British History, he died, at the age of 83, in 1892. The monument which stands at the top of Tennyson Down (renamed in his honour) was erected after his death. Before your visit... 1. Look at a couple of poems by Tennyson e.g. Crossing the Bar and Break, Break, Break. There are online analysis notes for both poems. Do a comparison with a poem from the GCSE Syllabus. 2. Can you identify which phrases in Tennyson’s poems can be linked to the place he lived - e.g. the sea on a stormy day, the downs in summer? 3. Investigate the frustrations of being in the public eye. Compare Tennyson with JK Rowling, both driven to move house as a result of media attention. -

Blackberry Barn Yarmouth Road | Shalfleet | Isle of Wight | PO30 4NB

Blackberry Barn Yarmouth Road | Shalfleet | Isle of Wight | PO30 4NB Blackberry Barn white format.indd 1 17/10/2019 12:15 Blackberry Barn white format.indd 2 17/10/2019 12:15 Blackberry Barn white format.indd 3 17/10/2019 12:15 STEP INSIDE Blackberry Barn This beautiful barn conversion has been delightfully upgraded to provide character features, with light modern accommodation. The property offers lots of features throughout and is provided with extensive gardens, paddocks and stables. The gated driveway into the home leads into an attractive courtyard area, where a double garage and ample off-road parking is granted to the occupants. The large entrance hall to the home is a welcoming area in which to greet guests, with an attractive staircase leading up to the first floor. The lounge is a beautiful light room and has an attractive central fireplace and views to both the front and rear of the property. The dining area is accessed from here and again gives a superb vantage point over the rear, more formal gardens, ensuring you may appreciate your location over a family Sunday lunch. The kitchen has been upgraded recently and offers attractive light coloured units and ample space for a dining table overlooking the rear paddocks. The current owner has fitted full length doors and windows providing ample natural light and an open outlook. In addition, you will find a well-equipped utility room for all the noisy appliances, with access out the to the rear garden. The first floor has three double bedrooms and a large family bathroom, as well as the master bedroom offering en-suite shower room. -

A Dictionary of the Isle of Wight Dialect, and of Provincialisms Used in the Island; with Illustrative Anecdotes and Tales; to W

y ; A DICTIONARY OF THE ISLE OF WIGHT DIALECT, And of ProYincialisins used in the Island WITH ILLUSTRATIVE ANECDOTES AND TALES; TO WHICH 18 APPENDED THE CHEISTMAS BOYS' PLAY, AN ISLE OF WIGHT " HOOAM HARVEST," AND SONGS SUNG BY THE PEASANTRY; FORMING % ¥tjfa$nri| uf %mn\nv ^nnmv^s nnt ©ustoms OF FIFTY YEARS AGO. BY W. H. LONG. (Subscribers' Edition.) London : REEVES & TURNER, 196 Strand, W.C. Isle of Wight : G. A. BRANNON & CO., "COUNTY PRESS," St, James's Square, Newport, 1886, LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS. Mrs. Aston, Bargato Street, Southampton. J. R. Blake, Esq., Stone House, Blackwater, I.W. A. Brannon, Esq., Gatcombe Newbarn, I.W. Lieut.-Gen. The Hon. Somerset J, G. Calthorpe, J. P., Woodlands Vale, Ryde, I.W. J. L. Cantelo, Esq., River Avon Street, Liverpool. J. F. Childs, Esq., Southsea. C. Conquest, Esq., 66 Denbigh Street, London. J. Cooke, Esq., Langton House, Gosport. The Rev. Sir W. H. Cope, Bart., Bramshill, Hants. Colonel Crozier, West Hill, Yarmouth, I.W. Colonel L. D. H. Currie, Ventnor, I.W. Dr. G. H. R. Dabbs, Highfields, Shanklin, I.W. A. Harbottle Estcourt, Esq., Deputy Governor of the Isle of Wight, Standen Elms, I.W. Sidney Everett, Esq., Fairmount, Shanklin, I.W. A. T. EvERiTT, Esq., Portsmouth. W. Featon Fisher, Esq., St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London. J. Lewis Ffytche, Esq., F.S.A., Freshwater, I.W. Mrs. PYeming, Roude, I.W. T. Francis, Esq., Havant. Messrs. W. George's Sons, Bristol. J. Griffin, Esq., J. P., Southsea. Dr. J. Groves, Carisbrooke, I.W. A. Howell, Esq., Carnarvon, Southsea. T. -

Arts, Literary & History Trail

Arts, Literary & History Trail - FRESHWATER - KS3 Alfred, Lord Tennyson Poet Laureate Resident at Farringford House, Freshwater Tennyson was born in Lincolnshire in 1809 and attended Trinity College, Cambridge in 1827 where he received The Chancellor’s Gold Medal (a prestigious award given for poetry) in 1829. His frst solo collection of poems were published soon after. Poetry wriritng was important to Victorians as there was no recorded music at this time. When Tennyson’s poem ‘Maud’ (written in 1854-55) became a frm favourite with British Society, Alfred Lord Tennyson was able to buy Farringford House (which is now a hotel), on the Isle of Wight, which he initially rented with his wife from 1853. In 1850, he was made Poet Laureate and he held this post for forty years. Heralded as one of the greatest poets in British History, he died, at the age of 83, in 1892. The monument which stands at the top of Tennyson Down (renamed in his honour) was erected after his death. Before you visit: 1. Research the life of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (he had a large family which was dominated by a ‘diffcult’ patriarch. 2. Build a timeline of Tennyson’s life which includes his works and major life events (you could use this as a basis to produce a biography of the poet). 3. Look at a couple of poems by Tennyson e.g. The Eagle, and Break, Break, Break. There are online analysis notes for both poems. 4. Poets and writers in the Victorian era experienced a similar type of fame to that of pop stars today. -

Italian Travel Sketches &C., Translated by Elizabeth A. Sharp, from The

THE SCOTT LIBRARY, ITALIAN TRAVEL SKETCHES, &C. ITALIAN TRAVEL SKETCHES, &c, BY HEINRICH HEINE. TRANS- LATED BY ELIZABETH A. SHARP. From the Original With Prefatory Note from the French of Theophile Gautier. London: Walter Scott, Ltd., 24 Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row, 23,/t CONTENTS. ITALIAN TRAVEL SKETCHES : PAGE THE JOURNEY FROM MUNICH TO GENOA . 3 THE TOWN OF LUCCA . IOO LATER NEWS . .165 CONCLUSION . .168 THE TEA-PARTY . .173 THE FRENCH STAGE : CONFIDENTIAL LETTERS ADDRESSED TO M. AUGUST LEWALD. I. ERNST RAUPACH . .176 II. GERMAN AND FRENCH COMEDY . .185 III. PASSION IN FRENCH TRAGEDY . 193 IV. THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL LIFE ON THE TRAGIC DRAMA IN FRANCE . 2OO V. THE IMPORTANCE OF NAPOLEON FOR THE FRENCH STAGE .... 2OQ VI. ALEXANDRE DUMAS AND VICTOR HUGO . 2l8 VII. COMEDY IN ENGLAND, FRANCE, AND GER- MANY ...... 228 VIII. THE STAGE -POETS OF THE BOULEVARDS THEATRES ..... 236 APPENDIX: GEORGE SAND . .244 NOTE. IT has been thought advisable to omit from this volume the second part of the Italienische Reisebilder; and, as of more general interest, to add the hitherto untranslated The French Stage: Confidential Letters addressed to M. August Lewald. PREFATORY STUDY ON HEINRICH HEINE. BY THEOPHILE GAUTIER. THE last time that I saw Heinrich Heine was a few weeks before his death ; I had to write a short notice for the re-issue of his works. He lay on the bed where, accord- ing to the doctors, a slight indisposition first held him, but whence he had not been able to rise therefrom for eight years. One was always sure of finding him, as he himself used to say; yet, little by little, solitude encom- passed him more and more; hence his exclamation to Berlioz, on the occasion of an unexpected visit : "You " come to see me ! you are as original as ever ! It was not that he was less loved or less admired, but life entices away with it the most faithful hearts, in spite of themselves: only a mother or a wife would never abandon so persistent a death-agony. -

STEALING DYLAN from WOODSTOCK When the World Came to the Isle of Wight Volume One: Stealing Dylan from Woodstock

When the World Came to the Isle of Wight VOLUME ONE STEALING DYLAN FROM WOODSTOCK When the World Came to the Isle of Wight Volume One: Stealing Dylan from Woodstock Published by Medina Publishing Ltd. 310 Ewell Road Surbiton Surrey KT6 7AL medinapublishing.com © Ray Foulk 2015 Designed by Kitty Carruthers ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909339-50-7 Paperback: 978-1-909339-49-1 Printed and bound by Toppan Leefung Printing Ltd CIP Data: A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library Ray Foulk asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. When the World Came to the Isle of Wight VOLUME ONE STEALING DYLAN FROM WOODSTOCK A personal account by Festival organiser RAY FOULK written & compiled with Caroline Foulk To Mother Dear CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Dramatis Personæ x Prologue xiii 1 Alfred Lord Tennyson 1 2 Prospecting 11 3 I Whisper 21 4 To Hell and Back 39 5 How About Bob Dylan? 53 6 Bob Wants to Meet You 61 7 Seven-and-a-Half Years 91 8 Help Bob Dylan Sink the Isle of Wight 115 9 We Cannot Control the Morals of 100,000 People 151 10 Serving the Master Well 179 11 Great To Be Here, Sure Is 211 12 Self Portrait 247 13 The Backlash 265 Epilogue: Electric Ladyland 271 Book Quotations & Song Titles 277 Picture Credits 278 Bibliography 281 Index 283 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Just get me an electric lawnmower he great joy of compiling this personal and socio-cultural history has been in rekindling so many past associations and friendships. -

Cowes the World's Most Famous Yachting Destination

Belfast | 1 Alum Bay. Credit: Visit Isle of Wight Cowes The world’s most famous yachting destination and a unique port-of-call Boutique destination and gem of the UK South Coast, Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, is ideally located and an economical stopover for the Northern European luxury cruise market. The coastal town of Cowes, an up-and-coming cruise port-of-call and the Isle of Wight beyond offer the perfect destination for cruise operators looking to cater to current demand for experiential and personalised travel, whilst still delivering a beneficial income stream for cruise lines. The sheltered anchorages for small to medium-sized cruise ships provide ample swinging room with a short tender run to Trinity Landing in Cowes for disembarkation. Cruise passengers come ashore at Trinity Landing on The Parade, next to Henry VIII’s Cowes Castle, home to the prestigious Royal Yacht Squadron and in the heart of Cowes. Individual and eclectic shops, art galleries, restaurants and cafés, and local artisan food and drinks producers line Cowes town’s charming streets. Cowes and the Isle of Wight deliver exceptional visitor appeal with cruise guests able to visit world-famous tourist attractions and enjoy an up-market selection of bespoke, memorable experiences. Cowes Harbour Commission is facilitating the ongoing development by shoreside tour operators of an enhanced range of authentic and exclusive excursions for discerning travellers. Destination experiences at Cowes, Isle of Wight include, for example: a royalty, yacht racing and rigging walking tour of Cowes, an exhilarating RIB ride to The Needles, an exploration by bicycle of Victorian history in Cowes and East Cowes, a lecture tour or English afternoon tea at Royal Osborne House, a guided visit to Ventnor Botanic Gardens, Carisbrooke Castle, Farringford House – Lord Tennyson’s idyll, golf at Freshwater, an expert tour at Mottistone Gardens, a chauffeur-driven panoramic tour in vintage cars, and other tailor-made trips on the Island that’s known as “England in miniature”. -

No Delicate Flower: Victorian Floral Symbolism's Mediation of Social

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-10-2017 10:30 AM No Delicate Flower: Victorian Floral Symbolism’s Mediation of Social Issues in Selected Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Alfred Tennyson, John Ruskin, and Isabella Bird Bishop Christine Penhale The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Matthew Rowlinson The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Christine Penhale 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Penhale, Christine, "No Delicate Flower: Victorian Floral Symbolism’s Mediation of Social Issues in Selected Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Alfred Tennyson, John Ruskin, and Isabella Bird Bishop" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4990. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4990 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract No Delicate Flower: Victorian Floral Symbolism’s Mediation of Social Issues in Selected Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Alfred Tennyson, John Ruskin, and Isabella Bird Bishop examines floral symbols in the writings of four Victorian authors. Although a large body of work exists on the Romantic literary symbol, its Victorian counterpart is often ignored: Barrett Browning, Tennyson, Ruskin, and Bird Bishop use floral symbols in their work as outward-looking instruments, in contrast to the more inward-looking Romantic symbol, to help understand changing social conditions and address real-world concerns. -

R Martin Report

FARRINGFORD FRESHWATER ISLE OF WIGHT Analytical Record (RCHME 1996) LEVEL III Report prepared August - October 2008 ADDRESS: Bedbury Lane, Freshwater, Isle of Wight. PO40 9PE SITE NAME: Farringford MONUMENT TYPE: Country House SUB-DESCRIPTOR: marine residence LISTED BUILDING STATUS: I DATE OF LISTING: 18th January 1967 LISTED BUILDING Uid: 393058 NMR Unique Identifier: 459498 NGR: SZ 3373 8617 PARISH: Freshwater DISTRICT: Isle of Wight LOCAL PLANNING AUTHORITY: Isle of Wight Council Research and compilation: R.S.J. Martin BA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.00 INTRODUCTION 2.00 GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.00 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 4.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 1: pre 19th century The Site 5.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 2: 1802 Construction of Farringford Lodge. 6.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 3: 1805 – 1823 Development of Farringford Hill. 7.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 4: 1825 – 1844 Additions by John Hamborough. 8.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 5: 1856 – 1892 Additions by Alfred Lord Tennyson. 9.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 6: 1892 – 1939 Additions by Hallam Tennyson. 10.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 7: 1945 – 1963 Hotel: Thomas Cook. 11.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 8: 1960 – 1990 Hotel: Fred Pontin. 12.00 ARCHITECTURAL AUDIT (EXTERNAL) 13.00 ARCHITECTURAL AUDIT (INTERNAL) 14.00 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15.00 SOURCES OF INFORMATION and BIBLIOGRAPHY GLOSSARY APPENDICES: A Historical Note on Freshwater Parish B Place-name Derivation C Rushworth D Parish Poor Rate E Regency Georgian Architecture F 19th Century Guide Books G Original House H Reverend Seymour I The Manor of Priors Freshwater J Williams-Ellis Report 1945 K Census L John Plaw M Skirting-board depths N Brick Analysis Note on Room Nomenclature In the report, the rooms of the house are referred to, according to their modern use, rather than their original function. -

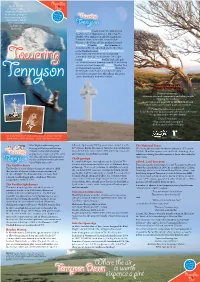

Tennyson Down, with Views Across Headon Warren to the Solent and the Mainland Beyond

Leave the car Ramblesby at home – take a Bus Southern Vectis bus The to the Isle of Wight’s best way to see the most inspiring walks. Island Just use the handy Towering QR code inside to find your Tennyson bus route Description A walk around the wild western tip of the Isle of Wight taking in Alum Bay, The Needles, West High Down and the magnificent Tennyson Down, with views across Headon Warren to the Solent and the mainland beyond. Distance 4.4 miles. Start Bus terminus at Alum Bay at The Needles Park, via the No. 7 bus or the Needles Breezer. Access information Many steps and some hills. Open downland countryside with spectacular views. Often quite breezy. Refreshments Needles Park café, pub Towering etc. Warren Farm tea rooms (seasonal). New Battery refreshment kiosk (seasonal). Toilets Needles Park or Warren Farm tea room. GPS users Waypoints for this walk can be found at our web site www. iowramblers.com/page5.htm. All walks in this series Tennyson can be downloaded from this website. Countryside Code Respect Protect Enjoy Respect other people • Consider the local community and other people enjoying the outdoors • Leave gates and property as you find them and follow paths unless wider access is available Protect the natural environment • Leave no trace of your visit and take your litter home • Keep dogs under effective control Enjoy the outdoors • Plan ahead and be prepared • Follow advice and local signs This is the Wild West – with soaring coastal scenery, Victorian fortifications, a Poet Laureate – and a Cold War rocket site ! West Wight is a fascinating area A Bronze Age barrow, 3,500 years old, was excavated in the The National Trust bursting with history and heritage, 13th century, during the reign of Henry III. -

Alfred, Lord Tennyson 1 Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred, Lord Tennyson 1 Alfred, Lord Tennyson The Right Honourable Lord Tennyson FRS 1869 Carbon print by Julia Margaret Cameron Born 6 August 1809 Somersby, Lincolnshire, England United Kingdom Died 6 October 1892 (aged 83) [] Lurgashall, Sussex, England United Kingdom Occupation Poet Laureate Alma mater Cambridge University Spouse(s) Emily Sellwood (m. 1850–w. 1892) Children • Hallam Tennyson (b. 11 August 1852) • Lionel (b. 16 March 1854) Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular British poets.[1] Tennyson excelled at penning short lyrics, such as "Break, Break, Break", "The Charge of the Light Brigade", "Tears, Idle Tears" and "Crossing the Bar". Much of his verse was based on classical mythological themes, such as Ulysses, although In Memoriam A.H.H. was written to commemorate his best friend Arthur Hallam, a fellow poet and fellow student at Trinity College, Cambridge, who was engaged to Tennyson's sister, but died from a brain haemorrhage before they could marry. Tennyson also wrote some notable blank verse including Idylls of the King, "Ulysses", and "Tithonus". During his career, Tennyson attempted drama, but his plays enjoyed little success. A number of phrases from Tennyson's work have become commonplaces of the English language, including "Nature, red in tooth and claw", "'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all", "Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die", "My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure", "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield", "Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers", and "The old order changeth, yielding place to new". -

Farringford Hotel Freshwater Isle of Wight

FARRINGFORD HOTEL FRESHWATER ISLE OF WIGHT Analytical Record (RCHME 1996) LEVEL III Report prepared August - October 2008 ADDRESS: Bedbury Lane, Freshwater, Isle of Wight. PO40 9PE SITE NAME: Farringford Hotel. MONUMENT TYPE: Country House SUB-DESCRIPTOR: marine residence LISTED BUILDING STATUS: I DATE OF LISTING: 18th January 1967 LISTED BUILDING Uid: 393058 NMR Unique Identifier: 459498 NGR: SZ 3373 8617 PARISH: Freshwater DISTRICT: Isle of Wight LOCAL PLANNING AUTHORITY: Isle of Wight Council Research and compilation: R.S.J. Martin BA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.00 INTRODUCTION 2.00 GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.00 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 4.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 1: pre 19th century The Site 5.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 2: 1802 Construction of Farringford Lodge. 6.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 3: 1805 – 1823 Development of Farringford Hill. 7.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 4: 1825 – 1844 Additions by John Hamborough. 8.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 5: 1856 – 1892 Additions by Alfred Lord Tennyson. 9.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 6: 1892 – 1939 Additions by Hallam Tennyson. 10.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 7: 1945 – 1963 Hotel: Thomas Cook. 11.00 THE PHASES OF DEVELOPMENT PHASE 8: 1960 – 1990 Hotel: Fred Pontin. 12.00 ARCHITECTURAL AUDIT (EXTERNAL) 13.00 ARCHITECTURAL AUDIT (INTERNAL) 14.00 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15.00 SOURCES OF INFORMATION and BIBLIOGRAPHY GLOSSARY APPENDICES: A Historical Note on Freshwater Parish B Place-name Derivation C Rushworth D Parish Poor Rate E Regency Georgian Architecture F 19th Century Guide Books G Original House H Reverend Seymour I The Manor of Priors Freshwater J Williams-Ellis Report 1945 K Census L John Plaw M Skirting-board depths N Brick Analysis Note on Room Nomenclature In the report, the rooms of the house are referred to, according to their modern use, rather than their original function.