Anabaptist Walk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Crown Place, Earl Street, London EC2A

London 30 Crown Place Pinsent Masons 30 Crown Place Earl Street London EC2A 4ES United Kingdom T: +44 (0)20 7418 7000 F: +44 (0)20 7418 7050 Liverpool Street station By Underground Liverpool Street station is the nearest underground station – approximate commute time 5 mins (Central, Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines). Exit the underground station onto the main National Rail concourse. Just to the left of platform 1 on the main concourse, exit the station via the Broadgate Link Shops arcade, towards Exchange Square. Continue right, along Sun Street Passage and then up the stairs onto Exchange Square. At the top of the stairs, take the first left towards Appold Street. Walk down the stairs, and at the bottom, cross over Appold Street onto Earl Street. Continue left along Earl Street and we are situated on the right hand side. Moorgate station Approx journey time 8-10 minutes. (Northern, Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines). Exit the station via Moorgate East side onto Moorgate. Turn right and walk north (towards Alternatively, take the 8-15 minutes. Approx. total Location Finsbury Pavement). Continue Heathrow Express to journey time is 35 minutes. Pinsent Masons HQ office is along Finsbury Pavement until Paddington and change for the located on the right hand side you reach Finsbury Square. Circle or Hammersmith & City From Stansted Airport of Crown Place when coming The Stansted Express runs line to Liverpool Street. Approx. from Moorgate or Liverpool between the airport and Street. Turn right into Finsbury Square journey time is 40 minutes. and continue straight ahead Liverpool Street every 15 into Sun Street. -

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal July 2018 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Alison Bennett, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 2/8/18 Reviser(s): Alison Bennett Date of last revision: 31/8/18 Date Printed: Version: 2 Status: Summary of Changes: Circulation: Required Action: File Name/Location: Approval: (Signature) 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 5 3 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers .................................................................................. 7 4 The London Borough of Islington: Historical and Archaeological Interest ....................... 9 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Prehistoric (500,000 BC to 42 AD) .......................................................................... 9 4.3 Roman (43 AD to 409 AD) .................................................................................... 10 4.4 Anglo-Saxon (410 AD to 1065 AD) ....................................................................... 10 4.5 Medieval (1066 AD to 1549 AD) ............................................................................ 11 4.6 Post medieval (1540 AD to 1900 AD).................................................................... 12 4.7 Modern -

Kreston-Reeves-London-Map.Pdf

Old t C Stree u Street ld r O t S a G i h A5201 n o o A1209 s r R w e G d d e r d e i a l l et a t o tre t c R S B100 A501 R ld Ea h en o O s re Clerkenwell a te H G d r i al n g Bethn Third Floor, 24 Chiswell Street S h d B t t a S u e A5201 o London EC1Y 4YX t n e R h r t Shoreditch i d n l S a C i o St.Lukes l R a R i n t t well r en y A1 o Tel: 033012 41399 Fax: 020 7382 1821 Clerk o u s w l R i C A1202 DX 42614 CHEAPSIDE S o N W t a A10 A F d J Barbican [email protected] a l o d r e r h B i n n r www.krestonreeves.com r s g i c g P d S k a t P r o t a r B100 CCh l n his Old L e cu A406 e ne well r Farringdon a St a i e L ree R t C g n t n Spitalfields h o o M1 rt L Barbican P e o J3 a Finsbury N S Market d Centre t Square Liverpool r A201 A406 e A1 A12 e Street t e E t l t J1 Moorgate do e field S a n t Brush S a A10 g t C r g A406 Smithfield See Inset o o s o p m Market t o A12 S M h m A5 F ld is H a St.Bartholomews e L e ol i iv B M A13 bo r f e r A40 rn r S rp c A501 - A1211 t o i m re ol d i H London Wallll lo et a V d l ia L B l du P ond Station e ct on t s S LONDON W e Entrance e t i al x A11 n l e r A406 e g t S Aldgate A40 t t d S a o East A4 G g d H n r r a t M4 A2 N es t o S J1 A205 ew ha o ro u h S m S nd ig ga St o B H t te ree s Aldgate l A13 r t h e A202 St M d d t e l c p r it a e e c h e Bank of O u h c tr A3 t St.Pauls h S A205 England c W m A316 A2 C St e a St.Pauls he edle h L r aps dne c ra e uth Circula L ide ea a B A3 So A205 udga Cathedral Thr r m A20 te G Hill Poul a Str try M Fleet eet N Royal Exchange n e i n S w City By Underground Cornhill Leadenhall t Stree o t M B ri Liverpool Street Thameslink DLR a r t Mansion Bank e e e s n Liverpool Street is on the Central, Metropolitan, Circle and S tr House A10 s t h S Whitechapel Hammersmith & City Lines. -

1 Finsbury Circus

0 1 Finsbury Circus Local Amenities Guide CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 MISSION & VISION STATEMENT 4 THE MANAGEMENT TEAM 5 OPERATIONAL HOURS 6 FACILITIES & SERVICES 7 FIRE EVACUATION PROCEDURES 8 YOUR LOCATION 9 TRANSPORTATION 10 LOCAL AMENITIES 13 2 NEED TO KNOW 33 INTRODUCTION The Local Amenities Guide has been produced for the benefit of the occupiers at 1 Finsbury Circus. It’s a brief overview about the procedures and policies in the building and the services provided by the Landlord. GOOD TO KNOW We have a beautiful listed Boardroom that is located at Basement level and can be booked by our occupiers subject to availability and at no cost. The room consists of a large round table, 15 chairs and a piano. To check for availability, please contact our Front of House Team on 0207 448 7070 or [email protected] The property is managed by CBRE on behalf of the Landlord with a fantastic team of outsourced specialist supplier partners for cleaning, maintenance, security and front of house who pride themselves on service excellence. BUILDING HISTORY Sir Edwin Lutyens designed the original building of 1 Finsbury Circus, it has the honour of being listed as a Grade ΙΙ* building. 1 Finsbury Circus opened in 1925 as Britannic House and served the Anglo-Persian Oil Company up until 1967, which was then renamed The British Petroleum Company (BP) in 1954. At the approach of war in 1939, City engineers visited Britannic House to make air raid precaution recommendations, classifying it as “a veritable fortress”. Greycoat PLC purchased the building in 1986, one of Britain’s leading commercial developers. -

GIPE-034178.Pdf (2.847Mb)

RECONSTRUCTION IN THE CITY OF LONDON Interim Report to the Improvements and Town Planning Committee by the Joint Consultants. March, I 946. ..... · C. H. HOLDEN, Litt. D., F.R.I.B.A., 1I.T.P.I. W. G. HOLFORD, ~!.A., A.R.I.B.A., ~I.T.P.I. REPORT-IMPROVEMENTS AND TOWN ------ ~· PLANNING COMMITTEE. To be presented 17th July, 1946. To the Right Honourable The Lord Mayor, Alde-;~8- of the City of London in Common Council assembled. We, whose names are hereunto subscribed, of your Committee for Improvements and Town Planning have the honour to submit to your Honourable Court the Interim Report of the Consultants appointed under the authority given on the 25th July, 1945, to advise the Corporation in regard to the provisional plan for the re-development of the City, together with the letter of the Minister of Town and Country Planning and all criticisms received, and to report generally thereon. Immediately upon receipt of the Interim Report, andpending our consideration of the tentative and preliminary proposals therein contained, we deemed it desirable that every M~Jmber of the Court should be afforded the earliest opportunity of perusing the Document, and we accordingly instructed the Town Clerk to arrange for the prompt circu lation thereof with a request that, pending our Report thereon, the contents should be regarded as in the highest degree confidential, and we trq.st-that our action in this regatd meets with the approval of your Honourable Court. We have duly proceeded in the consideration of the varioll)l proposals contained in the Interim Report, and on our instructions Mr. -

125 Finsbury Pavement, EC2 125 Finsbury Pavement, London EC2A 1NQ

AVAILABLE TO LET 125 Finsbury Pavement, EC2 125 Finsbury Pavement, London EC2A 1NQ Office for rent, 2,637 - 4,833 sq ft, P.O.A Veronika Sillitoe [email protected] For more information visit https://realla.co/m/29613-125-finsbury-pavement-ec2-125-finsbury-pavement Chris Halliwell [email protected] 125 Finsbury Pavement, EC2 125 Finsbury Pavement, London EC2A 1NQ Newly available flexible offices in a high quality office More information building, adjacent to Moorgate station. 125 Finsbury Pavement presents high quality office accommodation and Visit microsite lifestyle amenities, which would suit both City and City fringe occupiers. https://realla.co/m/29613-125-finsbury-pavement-ec2-125-finsbury- The building is located on the west side of Finsbury Pavement, between pavement Moorgate and Finsbury Square. Veronika Sillitoe The building benefits from excellent transport links, being within a two minute Ingleby Trice walk of Moorgate station and Liverpool Street station, with the benefit of easy 020 7029 3610 access to Elizabeth Line which is due to open at the end of 2018. [email protected] Highlights George Haworth The part 2nd floor is fitted out Ingleby Trice Four pipe fan coil air conditioning 020 7029 3625 Raised floor [email protected] LG7 compliant light fittings 2.7m typical floor to ceiling height Chris Halliwell 3 passenger lifts Contemporary entrance with a 24/7 manned reception Cushman & Wakefield Secure bicycle storage and showers 020 3296 2010 [email protected] Property details Rent P.O.A Quote reference: RENT-29613 Viewings strictly through joint sole agents. -

The London Gazette, 15Th March 1974 3475

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 15TH MARCH 1974 3475 Name of Company: BELSAY ARCADE GARAGE Name of Company: N. BLOOM & CO., LIMITED. LIMITED. Nature of Business: BOOT AND SHOE MANU- Nature of Business: MOTOR CAR DEALERS and FACTURERS REPAIRERS. Address of Registered Office: "Albion House", 87-89 Address of Registered Office: Lloyds Banks Chambers, Aldgate High Street, London EC3N 1LH. Collingwood Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 1JP. Liquidator's Name and Address: Sidney Joseph Robinson, Liquidators' Names and Addresses: William Lindop Hall, F.C.I.S., of L. G. Darling & Co., 87-89 Aldgate High 70 Finsbury Pavement, London EC2A 1SX and William Street, London EC3N 1LH. Gawen Mackey, 67 Chiswell Street, London EC1Y 4SY. Date of Appointment: 12th March 1974. Date of Appointment: 27th February 1974. By whom Appointed: Members. , (249) By whom Appointed: Members. (179) Name of Company: THE STEPNEY SHOE Name of Company: PRINTERS HEATERS LIMITED. MANUFACTURING COMPANY LIMITED. Nature of Business: MANUFACTURERS of COMPOS- Nature of Business: PROPERTY INVESTORS. ING MACHINE HEATERS and EQUIPMENT. Address of Registered Office: "Albion House", 87-89 Address of Registered Office: Capel House, New Broad Aldgate High Street, London EC3N 1LH. Street, London EC2M 1JS. Liquidator's Name and Address: Sidney Joseph Robinson, Liquidator's Name and Address: Frank Ivor Read, Capel F.C.I.S., of L. G. Darling & Co., 87-89 Aldgate High House, New Broad Street, London EC2M 1JS. Street, London EC3N 1LH. Date of Appointment: 8th March 1974. Date of Appointment: 12th March 1974. By whom Appointed: Members. (269) By whom Appointed: Members. (248) Name of Company: LEIGHSHIRE ENTERPRISES Name of Company: NEWLAY INVESTMENT CO. -

Finsbury Circus Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD

City of London Finsbury Circus Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD Finsbury Circus Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Feb 2015 1 Introduction 4 Character Summary 5 1. Location and context 5 2. Designation history 6 3. Summary of character 6 4. Historical development 7 Early history 7 Medieval 7 Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries 8 Nineteenth century 10 Twentieth and twenty-first centuries 10 5. Spatial analysis 12 Layout and plan form 12 Building plots 12 Building heights 12 Views and vistas 13 6. Character analysis 14 Finsbury Circus 14 Circus Place 16 London Wall 16 Blomfield Street 17 Eldon Street 18 South Place 19 Moorgate 20 7. Land uses and related activity 21 8. Architectural character 21 Architects, styles and influences 22 Building ages 22 9. Local details 22 10. Building materials 23 11. Open spaces and trees 23 12. Public realm 25 Management Strategy 26 14. Planning Policy 26 National policy 26 London-wide policy 26 City of London Corporation policy 26 Protected views 27 Sustainability and climate change 27 15. Access and an Inclusive Environment 28 16. Environmental Enhancement 29 17. Transport 29 18. Management of Open Spaces and Trees 30 19. Archaeology 30 20. Enforcement 31 21. Condition of the Conservation Area 32 Finsbury Circus Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Feb 2015 2 Further reading and references 33 Appendix 34 Designated Heritage Assets 34 Listed Buildings 34 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 35 Additional considerations 35 Blue Plaques and Plaques 35 Contacts 36 Finsbury Circus Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Feb 2015 3 Introduction The present urban form and character of the City of London has evolved over many centuries and reflects numerous influences and interventions: the character and sense of place is hence unique to that area, contributing at the same time to the wider character of the City. -

Islington Local Plan Bunhill and Clerkenwell Area Action Plan

Islington Local Plan Bunhill and Clerkenwell area action plan September 2019 www.islington.gov.uk Islington Council Local Plan: Bunhill and Clerkenwell Area Action Plan - Regulation 19 draft, September 2019 For more information about this document, please contact: Islington Planning Policy Team Telephone: 020 7527 2720/6799 Email: [email protected] 1 Bunhill and Clerkenwell in context ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Strategic and non-strategic policies and site allocations .................................................... 4 Area profile ........................................................................................................................ 7 Demographics ................................................................................................................... 8 Planning context .............................................................................................................. 12 Challenges ...................................................................................................................... 13 2 Area-wide policies ..................................................................................................... 18 Policy BC1: Prioritising office use .................................................................................... 18 Policy BC2: Culture, retail and leisure uses .................................................................... -

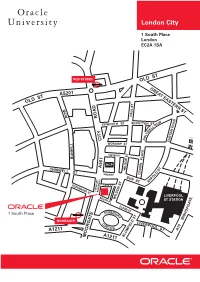

Oracle University London City

University Oracle 1 South Place OLD ST A5201 CHISWELL ST A1 ROW OLD STREET 2 MOORGATE 11 ILL BUNH R PMKRST OPEMAKER ROAD MOORGATE CITY EPWORT FINSBURY PAVE MENT A501 OT P SOUTH WORSHIP ST SQ LACK ST NCP F I U N HST A SBU C F R I E A1211 R I N L RY C S London City U B WILSON ST 1 South Place London S U EC2A 1SA R ST SCRUTTON ST PAUL ELD Y WILSON S T OLD ST S U ON N BLO S T G MFIELD ST ST CROWN PLACE HOLY R W E E L LL A I R T V A O E P W E R PO A P LD S O ST T E O R L CURTAIN ROAD N LIVERPOOL S ST STATION S T T A10 BIS HOP GATE Address By Air Oracle One South Place From Heathrow Airport, there are several ways to London EC2A 1SA reach Liverpool Street Station via the London University The Oracle building is a tall glass-fronted building Underground. on the corner of South Place and Finsbury Pavement. 1) Take the Piccadilly Line from Heathrow Central and you can continue on this line until Kings Cross/St. Pancras where you will need to change to either the Metropolitan or Circle Lines, east for Course Registration Liverpool Street. It is a requirement that all Oracle Education delegates 2) Take the Piccadilly Line from Heathrow Central register at reception prior to the commencement of to Gloucester Road or South Kensington stations each course. -

119-Fvl-1881-11-12-001-Single

CONTEN TS. A reflection came over us on November 5th , (Gunpowder Day,) which we think it well to communicate to our readers, " quantum valet." It is this, LEADERS 505 Consecration of a New Mark Lodge at Royal Masonic Institution for Hoys 506 Durban 510 that Time, " edax rerum," as the old poet has put it, seems to carry away on Ko'val Masonic Benevolent Institution 50^ Consecration nf the Southwark Lodge of Grand Lodge of Scotland 506 Royal Ark Mariners 510 its oblivious and yet destructive stream the memories and the struggles, the Consecration of thc Gilbert Greenall Chap- Annual Banquet of the Star Lod ge of In- crimes and conspiracies of men. We are told however by the " Press " that ter, No. 1250 505 struction , No. 1255 Sio Cavernous Masonry 5/07 Kni ghts Templar 511 this last 5th of November was a very " lively " day—one of the " most lively CoKKESI'ON'DENCE—¦ Obituary S11 Royal Masonic Institution for Girls JoS K EI '- IRTS OK M ASOXIC M EETINGS— for years," spent as it is, as most of us know in scenes and episodes partly The London Masonic Charitv Association 50S Craft Masonry 512 farcical, partly " saturnalian." If we to day, remembering the passionate Hamburg h Lotteries 50S Instruction , 514 Reviews 50S' Royal Arch C14 reprehension of the loya l English people which that great pre-dynamite crime Masonic Notes and Queries 509 Ancient and Accepted Rite 514 IWctiopolitan Masonic llencvolent Asso- Cryptic Masonry 514 of nearly 300 years ago unanimously evoked , and which is still represented ciation ; OIJ Amusements ^ 514 in grotesque proceedings and childish horseplay, giving the police much Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire 5C9 M asonic and General Tidings 51 j Provincial Grand Chapter of Cheshire JIO Lodge Meetings for \e„t Week J16 trouble, we repeat, we may well not pass over in silence this somewhat peculiar anniversary of national feeling as a protest against hurtful W E have great pleasure in announcing, as will be seen by an official com- conspiracies, secret societies, and unbridled fanaticism. -

Refurbished & Part Fitted out Office

4,833 FT2 (499 M2) REFURBISHED & PART FITTED OUT OFFICE TO LET 125FINSBURYPAVEMENT.COM Specification Part 2ND FLOOR 4,833 FT2 (499 M2) Refurbished Offices Net internal area Media Style Two Glazed Meeting Rooms & A Kitchenette Installed Four Pipe Fan Coil Air Conditioning (1:8 Occupancy) Raised Floor LED Lighting 3 Passenger Lifts Bicycle Racks, Showers & Lockers EPC Rating D (98) 24 Hour Security & Manned Reception RIVINGTON ST Terms OLD ST Terms upon application. GREAT EASTERN ST OLD ST ROW BUNHILL TABERNACLE ST WHITECROSS ST OLD ST GOLDEN LN LEONARD ST WILSON ST Viewings through joint sole agents CITY ROAD GOSWELL RD BONHILL ST CURTAIN RD WORSHIP ST DUFFERIN ST Veronika Sillitoe HAC FINSBURY SQ +44 (0)20 7029 3619 CHISWELL ST SUN ST APPOLD ST BISHOPSGATE [email protected] ALDERSGATE ST BARBICAN FINSBURY CENTRE PAVEMENT BROADGATE LONG LANE CITY ESTATE POINT WILSON ST George Haworth FORE ST MOOR LANE ELDON ST NSB FI URY C +44 (0)20 7029 3625 I R C U S [email protected] ST LONDON WALL LONDON WALL ST MARTIN'S BISHOPSGATE LE GRAND LIVERPOOL ST WOOD ST Emma Stratton GRESHAM ST COLEMAN ST MOORGATE KING EDWARD +44 (0)20 3296 4281 CAMOMILE STREET BASINGHALL ST [email protected] FOSTER LN CHEAPSIDE OLD BROAD ST KING ST BANK OF ENGLAND THREADNEEDLE ST BISHOPSGATE Chris Halliwell NEW CHANGE +44 (0)20 3296 2010 [email protected] Misrepresentation Act 1967: Ingleby Trice LLP and Cushman & Wakefield for themselves and for the vendor(s) or lessor(s) of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: 1.