20 Ropemaker Street Archaeology Desk Based Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Londons Warming Technical Report

Final Report 61 5. The Potential Environmental Impacts of Climate Change in London 5.1 Introduction There are several approaches to climate change impact assessment. These include: extrapolating findings from existing literature; fully quantitative, model-based simulations of the system(s) of interest; or eliciting the opinions of experts and stakeholders. All three approaches will be implemented in this section by a) reviewing the formal literature where appropriate, b) undertaking exemplar impacts modelling for specific issues identified through c) dialogue with stakeholders. Two workshops were held in May 2002 in order to engage expert and stakeholder opinion regarding the most pressing potential climate change impacts facing London. Following stakeholder consultation, five environmental areas were highlighted: 1) urban heat island effects (including London Underground temperatures); 2) air quality; 3) water resources ; 4) tidal and riverine flood risk and 5) biodiversity. Although these are addressed in turn – and where appropriate, case studies have been included – it is also acknowledged that many of these are cross-cutting (for example, river water quality impacts relate to flood risk, water resources and biodiversity). The final section delivers a summary of the most significant environmental impacts of climate change for London. Policy responses are addressed elsewhere. 5.2 Higher Temperatures 5.2.1 Context Throughout this section the reader is invited to refer to the downscaling case study provided in Section 4.7). Heat waves may increase in frequency and severity in a warmer world. Urban heat islands exacerbate the effects of heat waves by increasing summer temperatures by several more degrees Celsius relative to rural locations (see Figure 3.2b). -

IMPERIAL HALL, 104-122 CITY ROAD, OLD STREET, LONDON, EC1V 2NR Furnished, £775 Pw (£3,358.33 Pcm) + Fees and Other Charges Apply.*

IMPERIAL HALL, 104-122 CITY ROAD, OLD STREET, LONDON, EC1V 2NR Furnished, £775 pw (£3,358.33 pcm) + fees and other charges apply.* Available from 12th August 2019 IMPERIAL HALL, 104-122 CITY ROAD, OLD STREET, LONDON, EC1V 2NR £775pw (£3,358.33 pcm) Furnished • High spec ification duplex apartment • Private r oof terrace • Original features • Separate study • agency fees apply • EPC Rating = D • Council Tax = F Description A stunning example of a duplex, 2 bedroom, 2 bathroom property finished to an impeccable standard located in the popular Imperial Hall development in the heart of Old Street. The property benefits from being finished to the highest possible standard with a large open plan kitchen reception, retaining the original feature iron work. Further benefits include a large private terrace, a feature fish tank wall, a separate study room with glass roof giving an ideal light work space, 2 good sized bedrooms with large built in storage, high specification bathrooms, a further mezzanine guest or storage room, lots of storage, hand crafted oak fitted book shelving and a concierge service. Situation Imperial Hall and Old Street fall strategically between the City in the south and Angel Islington in the north, Clerkenwell and Soho in the west and Shoreditch Hoxton just to the east. Located in the Borough of Islington inside the Moorfields Conservation Area on City Road and seconds from Old Street Station on Old Street Roundabout, Imperial Hall is served by the Northern Line (Bank branch), rail and many bus connections making it is easy to get to and around. It’s a great area to live, work and enjoy, with enough amenities to make it pleasant, while maintaining enough characteristics to keep it interesting and original. -

30 Crown Place, Earl Street, London EC2A

London 30 Crown Place Pinsent Masons 30 Crown Place Earl Street London EC2A 4ES United Kingdom T: +44 (0)20 7418 7000 F: +44 (0)20 7418 7050 Liverpool Street station By Underground Liverpool Street station is the nearest underground station – approximate commute time 5 mins (Central, Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines). Exit the underground station onto the main National Rail concourse. Just to the left of platform 1 on the main concourse, exit the station via the Broadgate Link Shops arcade, towards Exchange Square. Continue right, along Sun Street Passage and then up the stairs onto Exchange Square. At the top of the stairs, take the first left towards Appold Street. Walk down the stairs, and at the bottom, cross over Appold Street onto Earl Street. Continue left along Earl Street and we are situated on the right hand side. Moorgate station Approx journey time 8-10 minutes. (Northern, Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines). Exit the station via Moorgate East side onto Moorgate. Turn right and walk north (towards Alternatively, take the 8-15 minutes. Approx. total Location Finsbury Pavement). Continue Heathrow Express to journey time is 35 minutes. Pinsent Masons HQ office is along Finsbury Pavement until Paddington and change for the located on the right hand side you reach Finsbury Square. Circle or Hammersmith & City From Stansted Airport of Crown Place when coming The Stansted Express runs line to Liverpool Street. Approx. from Moorgate or Liverpool between the airport and Street. Turn right into Finsbury Square journey time is 40 minutes. and continue straight ahead Liverpool Street every 15 into Sun Street. -

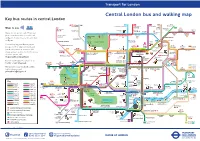

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

287 CITY ROAD EC1V 1AB Design & Access Statement | Rev P2 | March 2018

JFD-0379 GROUND FLOOR OF 287 CITY ROAD EC1V 1AB Design & Access Statement | Rev P2 | March 2018 287 City Road (Ground Floor) EC1V 1AB DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT JFD-0379 GROUND FLOOR OF 287 CITY ROAD EC1V 1AB Design & Access Statement | Rev P2 | March 2018 CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 SITE & CONTEXT 3.0 THE PROPOSED SCHEME 4.0 ACCESS & MOBILITY 5.0 PLANNING POLICY 6.0 FLOOD RISK 7.0 TRANSPORT JFD-0379 GROUND FLOOR OF 287 CITY ROAD EC1V 1AB Design & Access Statement | Rev P2 | March 2018 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Preamble 1.2 List of DB Architects Drawings This Design and Access Statement has been compiled to accompany the planning application for the JFD-0379-001-SITE & LOCATION PLANS_RevP ground floor of no. 287 City Road, Islington, EC1V 1AB. The application seeks the approval for the JFD-0379-005-EXISTING GROUND FLOOR _RevP change of use from Class A5 to Sui Generis for use as a Nail Bar. JFD-0349-006-EXISTING ELEVATIONS _RevP JFD-0349-007-EXISTING SECTION _RevP JFD-0349-010-PROPOSED GROUND FLOOR & BASEMENT PLAN _RevP JFD-0379-015 PROPOSED SECTION AA _RevP JFD-0379 GROUND FLOOR OF 287 CITY ROAD EC1V 1AB Design & Access Statement | Rev P2 | March 2018 2.0 SITE & CONTEXT 2.1 Site Description The application site is 287 City Road which is positioned within a terrace between City Garden Row and Remington Street. This application is concerned with the ground floor of no. 287 which consists of the single storey element forming part of the commercial street frontage to this stretch of City Road. -

Family Activities

Family activities Discover the secrets of Roman London at London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE. London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE is a cultural hub in the City of London showcasing the ancient Temple of Mithras, a selection of Roman artefacts, and contemporary art inspired by the site’s archaeology. Instructions Take a virtual tour of London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE with the free Bloomberg Connects app. Download it from your app store and use what you discover to complete these fun activities. Explore the Exhibition Challenges Did you know that artist Susan Hiller collected 70 songs about London and created an artwork called London Jukebox now on display at London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE? What is a jukebox? Colour in the jukebox >>>> What’s your favourite song about London? Use some of these words to write your own song lyrics: London lights sing roman discover Mithras city friends is you in artefact shine are street home the your magic and we archaeologist Play your favourite song, sing and dance along! londonmithraeum.com 2 Explore the Artefacts Case Challenge Using Bloomberg Connects, explore the virtual artefact case. See if you can find the following everyday objects left behind by the first Londoners. Coins The Bull Key Amulet Oil Lamp Tablet Shoe Flagon Mosaic Ring Challenge A mosaic is a piece of art created by assembling small pieces of coloured glass, ceramic, or stone into an image. Mosaic floors were a statement of wealth and importance in Roman times. Colour in the tiles to create a pattern or picture. londonmithraeum.com 3 Dot to Dot Challenge Using Bloomberg Connects uncover the mysteries of Mithras and solve the below puzzle. -

Document.Pdf

LONDON IS EVOLVING A CITY OF COLLIDING FORCES A CULTURAL CITY A CITY FOR CHALLENGERS AND EXPLORERS A CITY TO MOVE FORWARD WELCOME TO GRESHAM ST PAUL’S MOVE FORWARD THIS IS S T PA U L' S B WOW FACTOR Gresham St Paul’s has something a little different — unparalleled proximity to the global icon that is St Paul’s Cathedral. The building has a privileged location between some of London’s most prominent cultural landmarks, vibrant amenity and a global financial centre. An unofficial logo, St Paul’s Cathedral is our compass point for central London, marking the meeting point of cultural and commercial life in the city. Gresham St Paul’s enjoys A GLOBAL exceptional proximity to this icon. ICON A busy streetscape 340 St Paul’s receives over 1.5m visitors each year years as London’s most recognisable centrepiece 3 minute walk from Gresham St Paul’s View of the Cathedral from the 8th floor of Gresham St Paul’s 4 5 Barbican Centre GRESHAM ST PAUL'S Bank of England St Paul's Cathedral Liverpool St / Moorgate St Paul’s CUTTING EDGE Tate Modern The world’s most popular art museum is connected to St Paul’s by the Millennium Bridge CULTURE 8 Some of London’s leading cultural institutions are just a lunch break away. And there is more to come. A number of high-profile new cultural projects are set to open in 8 the immediate area, including the new Museum of London world-class cultural venues form the opening at West Smithfield Market in the coming years Culture Mile, all within and new concert hall for the London Symphony Orchestra. -

C257 London Wall and Blomfield Street Utilities WB FW Report.Pdf

London Wall & Blomfield Street Utilities Watching Brief Fieldwork Report, XSZ11 C257-MLA-T1-RGN-CRG03-50015 v2 Non technical summary This report presents the results of watching briefs carried out by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) on cable diversion works on the junction between Blomfield Street and London Wall, and a trial hole for the insertion of monitoring equipment outside 41/42 London Wall, both in the City of London, EC2. The utilities work was undertaken by UK Power Networks (UKPN) and the trial hole excavated for Thames Water. This report was commissioned from MOLA by Crossrail Ltd and is being undertaken as part of a wider programme to mitigate the archaeological implications of railway development proposals along the Crossrail route. This report covers a UKPN utilities diversion trench running down the centre of Blomfield Street, turning east on the northern carriageway of London Wall, and a trial trench adjacent to 41/42 London Wall. Given the proximity of the Roman and medieval City Wall, a Scheduled Monument (LO26P), fieldwork was focused around the junction between the two roads, and the immediate vicinity. The trial hole was located approximately 15m east of the junction between Moorgate and London Wall, in the southern carriageway. No archaeologically significant deposits were exposed in the trial hole adjacent to 41/42 London Wall. This archaeological watching brief followed requirement set out in a Scheduled Monument Deed under the Crossrail Act (2008). A further aim was to ensure that the works did not damage the Scheduled Monument, should the City Wall be encountered. The City Wall and associated deposits were left in situ. -

Finsbury Square, the City Finsbury Square

2016 FINSBURY SQUARE, THE CITY Welcome The first and still the best, at Smart we pride ourselves on creating that magic atmosphere that your guests will remember long after they leave. We offer the ultimate combination of spectacular themes, mesmerising entertainment, exquisite food and exceptional service. So bring your colleagues and friends, come dressed to impress and get ready for an avalanche of unforgettable experiences at ‘Après’. Greg Lawson CEO, Smart Group Contents STEP INSIDE APRÈS 6 TIMINGS, AVAILABILITY, WHAT’S INCLUDED 17 MENUS 19 DRINKS 20 PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR 22 WHAT MAKES A SMART CHRISTMAS PARTY? 24 BOOKING YOUR PARTY 29 NEXT STEPS 30 FIND US 32 ABOUT SMART 34 ‘APRÈS’ AT FINSBURY SQUARE - 5 6 - WWW.SMARTCHRISTMASPARTIES.CO.UK - 020 7836 1033 Step into an electrifying Après ski party in the heart of the City. This year Finsbury Square will be transformed into an ice cool Alpine wonderland. Make your way into the blizzard of snow and through the forest of magnificent fir trees before you find yourself in a clearing overlooking a bustling Alpine square. You are welcomed in from the cold where you shake off the fresh snow and dispose of your coats and bags. Gather round a roaring log fire and recline on the fur-lined seats as friendly staff serve you glasses of frosted fizz and exquisite canapés. ‘APRÈS’ AT FINSBURY SQUARE - 7 “The staff were blown away by the venue and event, it was great to see them enjoying themselves.” Axis Group UK 8 - WWW.SMARTCHRISTMASPARTIES.CO.UK - 020 7836 1033 Individual log cabins draped in festoon lighting and dappled with moon light are broken up by towering fir laden trees, forming the heart of Après. -

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

London Borough of Islington Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal July 2018 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Alison Bennett, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 2/8/18 Reviser(s): Alison Bennett Date of last revision: 31/8/18 Date Printed: Version: 2 Status: Summary of Changes: Circulation: Required Action: File Name/Location: Approval: (Signature) 2 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 2 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 5 3 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers .................................................................................. 7 4 The London Borough of Islington: Historical and Archaeological Interest ....................... 9 4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Prehistoric (500,000 BC to 42 AD) .......................................................................... 9 4.3 Roman (43 AD to 409 AD) .................................................................................... 10 4.4 Anglo-Saxon (410 AD to 1065 AD) ....................................................................... 10 4.5 Medieval (1066 AD to 1549 AD) ............................................................................ 11 4.6 Post medieval (1540 AD to 1900 AD).................................................................... 12 4.7 Modern -

250 City Road Changes in the City Continue 2–3

250 City Road Changes in the City continue 2–3 250 City Road London EC1 Designed by the world-renowned architects, Foster + Partners, 250 City Road will create a new landmark for London. Situated in a prime location between Angel and Old Street, 250 City Road is within walking distance of the City of London’s financial district, Tech City and the vibrant bars, restaurants and nightlife of Shoreditch. With the delights of Upper Street, Old Street and Silicon Roundabout less than a ten minute walk away, this is the perfect destination to work and relax. The scheme itself will offer a host of world class facilities including vibrant new cafes and restaurants, two acres of wi-fi enabled green spaces, public art and exceptional office and studio space for start-ups as well as a 4* nhow hotel. With stunning views in every direction, 250 City Road rises above its surroundings to bring this global city to your door. 250 City Road City changes continue Amenities An increasingly alluring trait of new build apartments is the amenities they come with. A CBRE survey recently found the convenience of having on site amenities, such as a pool and gym, was highly desired. The most popular amenities are a concierge and a gym, with both being used by well over 80% of residents. What’s more, 69% who didn’t have a pool wished they did! 250 City Road has taken all of this on board and will offer a range of amenities including: – Luxurious 20-metre pool – Spa with jacuzzi, sauna and steam room – Gym and rooftop fitness terrace – Residents’ lounge – 24 hour concierge -

Kreston-Reeves-London-Map.Pdf

Old t C Stree u Street ld r O t S a G i h A5201 n o o A1209 s r R w e G d d e r d e i a l l et a t o tre t c R S B100 A501 R ld Ea h en o O s re Clerkenwell a te H G d r i al n g Bethn Third Floor, 24 Chiswell Street S h d B t t a S u e A5201 o London EC1Y 4YX t n e R h r t Shoreditch i d n l S a C i o St.Lukes l R a R i n t t well r en y A1 o Tel: 033012 41399 Fax: 020 7382 1821 Clerk o u s w l R i C A1202 DX 42614 CHEAPSIDE S o N W t a A10 A F d J Barbican [email protected] a l o d r e r h B i n n r www.krestonreeves.com r s g i c g P d S k a t P r o t a r B100 CCh l n his Old L e cu A406 e ne well r Farringdon a St a i e L ree R t C g n t n Spitalfields h o o M1 rt L Barbican P e o J3 a Finsbury N S Market d Centre t Square Liverpool r A201 A406 e A1 A12 e Street t e E t l t J1 Moorgate do e field S a n t Brush S a A10 g t C r g A406 Smithfield See Inset o o s o p m Market t o A12 S M h m A5 F ld is H a St.Bartholomews e L e ol i iv B M A13 bo r f e r A40 rn r S rp c A501 - A1211 t o i m re ol d i H London Wallll lo et a V d l ia L B l du P ond Station e ct on t s S LONDON W e Entrance e t i al x A11 n l e r A406 e g t S Aldgate A40 t t d S a o East A4 G g d H n r r a t M4 A2 N es t o S J1 A205 ew ha o ro u h S m S nd ig ga St o B H t te ree s Aldgate l A13 r t h e A202 St M d d t e l c p r it a e e c h e Bank of O u h c tr A3 t St.Pauls h S A205 England c W m A316 A2 C St e a St.Pauls he edle h L r aps dne c ra e uth Circula L ide ea a B A3 So A205 udga Cathedral Thr r m A20 te G Hill Poul a Str try M Fleet eet N Royal Exchange n e i n S w City By Underground Cornhill Leadenhall t Stree o t M B ri Liverpool Street Thameslink DLR a r t Mansion Bank e e e s n Liverpool Street is on the Central, Metropolitan, Circle and S tr House A10 s t h S Whitechapel Hammersmith & City Lines.