AFRICAN LITERATURE and the ENVIRONMENT: a STUDY in POSTCOLONIAL ECOCRITICISM By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature By Derek M. Ettensohn M.A., Brown University, 2012 B.A., Haverford College, 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Derek M. Ettensohn This dissertation by Derek M. Ettensohn is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ___________________ _________________________ Olakunle George, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ___________________ _________________________ Timothy Bewes, Reader Date ___________________ _________________________ Ravit Reichman, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ___________________ __________________________________ Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of “Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature” by Derek M. Ettensohn, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2014. This project evaluates the twinned discourses of globalism and humanitarianism through an analysis of the body in the postcolonial novel. In offering celebratory accounts of the promises of globalization, recent movements in critical theory have privileged the cosmopolitan, transnational, and global over the postcolonial. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of globalism, these theorists have often turned to transnational fiction as supplying a corrective dose of humanitarian sentiment that guards a global affective community against the potential exploitations and excesses of neoliberalism. While authors such as Amitav Ghosh, Nuruddin Farah, and Rohinton Mistry have been read in a transnational, cosmopolitan framework––which they have often courted and constructed––I argue that their theorizations of the body contain a critical, postcolonial rejoinder to the liberal humanist tradition that they seek to critique from within. -

99 Essential African Books: the Geoff Wisner Interview

99 ESSENTIAL AFRICAN BOOKS: THE GEOFF WISNER INTERVIEW Interview by Scott Esposito Tags: African literature, interviews Discussed in this interview: • A Basket of Leaves: 99 Books that Capture the Spirit of Africa, Geoff Wisner. Jacana Media. $25.95. 292 pp. Although it is certain to one day be outmoded by Africa’s ever-changing national boundaries, for now Geoff Wisner’s book A Basket of Leaves offers a guide to literature from every country in the African continent. Wisner reviews 99 books total, covering the biggest homegrown authors (Achebe, Coetzee, Ngugi), some notable foreigners (Kapuscinski, Chatwin, Bowles), and a host of lesser-knowns. The books were selected from hundreds of works of African literature that Wisner has read: how to whittle hundreds down to just 99 books to represent an entire continent? Wisner says reading widely was key, as was developing a “bullshit detector” for the “false” and “fraudulent” in African lit by living there and working with the legal defense of political prisoners in South Africa and Nambia. Full of sharp opinions and oft-overlooked gems, A Basket of Leaves offers a compelling overview of a continent and its literature—an overview one that Wisner is eager to supplement and discuss in person. —Scott Esposito Scott Esposito: To start, how did you conceive and develop A Basket of Leaves? Geoff Wisner: The idea developed rather slowly. For several years I was raising money for political prisoners in South Africa and Namibia. I edited a newsletter on Southern Africa and started to read authors like Nadine Gordimer and J.M. -

Melancholia and the Search for the Lost Object in Farah's Maps

A. E. Eruvbetine and Solo- Melancholia and the search for the mon Omatsola Azumurana A. E. Eruvbetine is a Professor of lost object in Farah’s Maps English at the University of Lagos, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] Solomon Omatsola Azumurana teaches in the Department of English, University of Lagos, Nigeria. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Melancholia and the search for the lost object in Farah’s Maps Maps, given its intriguing narrative thrusts and multi-axial thematic concerns, is arguably the most studied or analysed of Nur- rudin Farah’s nine prose fictions. The novel’s title as well as its synopsis has naturally dictated the focus of critics on the Western Somalia Liberation Front’s war efforts geared towards liberating the Ogaden from Ethiopian suzerainty and restoring it to Somalia. The nationalist fervour, the war it precipitates and its fallouts of a strife-ridden milieu have such a pervading presence in the novel that the personal experiences of the novel’s two major characters, Askar and Misra, are quite often discussed as basic allegories of ethnic and nationalistic rivalries. This paper focuses on the personal experiences of Farah’s two major characters. It contends that the private story of Askar and Misra is so compelling and central to the many issues broached in the novel that it deserves significant critical attention. Drawing upon Sigmund Freud’s and Melanie Klein’s concepts of melancholia, the paper explores how central the characters’ haunting sense of melancholia is to the happenings in Farah’s Maps. Keywords: Freud, Klein, melancholia, lost object, Maps (Nurrudin Farah). -

The Challenge of Gender Inequality

Econ Polit https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0095-5 CORRESPONDENCE Correspondence for 1/2018 Alberto Quadrio Curzio1,2 Ó Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 As Editor-in-Chief of this Journal it is a pleasure to write this editorial on the speech of Professor Bina Agarwal, who is also a distinguished member of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei founded in 1603—the world’s oldest Academy! I thank Professor Bina Agarwal for sharing with us the speech she delivered at the Balzan Prizewinners’ Interdisciplinary Forum held in Berne on 16 November 2017. I also thank the International Balzan Prize Foundation for giving us permission to publish the speech. As background, I share with our readers the citation highlighting the reasons given by the Foundation for awarding her the 2017 International Balzan Prize for Gender Studies: For challenging established premises in economics and the social sciences by using an innovative gender perspective; for enhancing the visibility and empowerment of rural women in the Global South; for opening new intellectual and political pathways in key areas of gender and development. This thoughtful and concise statement, and the bibliography published on Balzan’s website (http://www.balzan.org/en/prizewinners/bina-agarwal), highlights the originality and excellence of Bina Agarwal’s life time research, and her remarkably effective engagement with policy and legal change. I believe her contributions offer to economists a new paradigm on the economics of human and sustainable development, and institutional analysis. Let me stress some points which I find especially striking. Bina Agarwal has done sustained pioneering research not just in one field of economics but in several major fields, from a political economy and gender & Alberto Quadrio Curzio [email protected] 1 Universita` Cattolica, Milano, Italy 2 Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma, Italy 123 Econ Polit perspective. -

Women-Empowerment a Bibliography

Women’s Studies Resources; 5 Women-Empowerment A Bibliography Complied by Meena Usmani & Akhlaq Ahmed March 2015 CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES 25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market) New Delhi-110 001 Ph. 91-11-32226930, 322266931 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cwds.ac.in/library/library.htm 1 PREFACE The “Women’s Studies Resources Series” is an attempt to highlight the various aspect of our specialized library collection relating to women and development studies. The documents available in the library are in the forms of books and monographs, reports, reprints, conferences Papers/ proceedings, journals/ newsletters and newspaper clippings. The present bibliography on "Women-Empowerment ” especially focuses on women’s political, social or economic aspects. It covers the documents which have empowerment in the title. To highlight these aspects, terms have been categorically given in the Subject Keywords Index. The bibliography covers the documents upto 2014 and contains a total of 1541 entries. It is divided into two parts. The first part contains 800 entries from books, analytics (chapters from the edited books), reports and institutional papers while second part contains over 741 entries from periodicals and newspapers articles. The list of periodicals both Indian and foreign is given as Appendix I. The entries are arranged alphabetically under personal author, corporate body and title as the case may be. For easy and quick retrieval three indexes viz. Author Index containing personal and institutional names, Subject Keywords Index and Geographical Area Index have been provided at the end. We would like to acknowledge the support of our colleagues at Library. -

Re-Envisioning the Question of Postcolonial Muslim Identity: Challenges and Opportunities

Re-envisioning the Question of Postcolonial Muslim Identity: Challenges and Opportunities Dr. Jamil Asghar ABSTRACT: In our contemporary era of transnationalism, the issue of identity has assume unprecedented significance and scope. In this paper, I intend to discuss the complexities and nuances of the Muslim identity in the postcolonial literary discourses. One of the basic contentions of the paper is to find some pattern in the transnational and transcultural diversity presently characterizing the Muslim identity discourses. Hence, this paper is a plea to discover some kind of literary and discursive sharedness in the contemporary postcolonial Muslim writings. It has been observed that at this point in time the Muslim identity in not only subject to myriad influences, it is also a topic of heated and passionate debates. In fiction, memoirs, travel writing, media and cultural narratives, the issue of Muslim identity is invested with all kinds of representations ranging from uncouth explosive-bearing terrorists to friendly and sociable people. It has also been shown that the Orientalist legacy, far from being dead, is being given new lease on life by the highly ‘constructed’ and ‘worked over’ images of Muslims in the Western media. The large Muslim diasporic populations settled in the European countries are specifically bearing the brunt of such stereotypical depictions built by media persons, political commentators, analysts and ‘cultural experts’. Faced with this mighty discursive onslaught, the Muslim writers, novelists, poets, intellectuals have been responding variedly and with considerably mixed motives: acceptance, rejection, rectification, resistance, etc. Keywords: Identity, Muslim, diaspora, discourse, postcolonial, representation. Journal of Research (Humanities) 82 1.1. -

Bibliography

161 Bibliography Acosta, Pablo, and others (2007). What is the impact of international remit- tances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4249 (June). Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Adams, Richard H., Alfredo Cuecuecha and John M. Page (2008). The impact of remittances on poverty and inequality in Ghana. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4732 (September). Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Adato, Michelle, and Lawrence Haddad (2001). Targeting poverty through community-based public works programs: a cross-disciplinary assessment of recent experience in South Africa. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Discussion Paper, No. 121. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. Addison, Tony (2009). Chronic poverty in the global economy. European Jour- nal of Development Research, vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 174-178. Aizenman, Joshua (2005). Financial liberalization: how well has it worked for developing countries? FRBSF Economic Letter (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), No. 2005-06 (8 April), pp. 1-3. Akroyd, Stephen, and Lawrence Smith (2007). Review of public spending to agriculture: a joint DFID/World Bank study. London: United Kingdom Department for International Development; Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Alam, Asad, and others (2005). Growth, Poverty, and Inequality: Eastern Eu- rope and the Former Soviet Union. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Alderman, Harold, and Victor Lavy (1996). Household responses to public health services: cost and quality trade-offs.World Bank Research Observer, vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 3-22. Amsden, Alice H. (1989). Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industriali- zation. New York: Oxford University Press. -

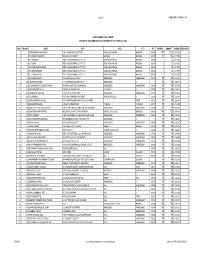

Unclaimed Dividend for 2002-03

1 of 72 ANNEXURE TO FORM 1 INV TANFAC INDUSTRIES LIMITED DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2002-2003 S.NO. FOL NO. NAME ADD1 ADD2 CITY PIN SHARES AMOUNT WARNO REMARKS 1 2 SARASWATHI NARAYANAN C/O L NARAYANAN CHETTIAR VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 101 121.2 2317604 2 4 T N KRISHNA MOORTHI 50 MAHAL 6TH STREET MADURAI MADURAI 625001 11 13.2 2317505 3 9 K R GANESAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317605 4 10 S S MITRA SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317606 5 11 S M THIRUNAVUKARASU SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317607 6 27 K N SUBRAMANIAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317608 7 29 C T RAMANATHAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317609 8 112 BACHUBHAI BHATT 19-B PANCHSHIL SOCIETY AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380013 50 60 2305488 9 200 YOGESH BHAVSAR F 12 VARDHMAN NAGAR FLATS AHMEDABAD 0 0 50 60 2320317 10 224 DWARKADAS GOVINDDAS PARIKH RADHIKA CAMP ROAD SHAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380004 50 60 2305098 11 229 KRISHNAMURTHY K A C/O MR K S ADINARAYAN PALAKKAD 0 678003 50 60 2324671 12 232 PADMAKANT DALVADI C/2 SUTIRTH APPARTMENT AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380015 50 60 2305633 13 298 P B SHARMA FLAT NO.4 ADINATH APARTMENT JAM NAGAR (GUJ) 0 361008 50 60 2323801 14 429 GOPALKRISHNA HALIYAL AT PO MOTAVAGHHCHHIPA TAL KILLA PARDI 0 PARDI 396125 50 60 2321186 15 556 SOMASUNDARAM K 2- SOUTH USMAN ROAD T. -

The India Cements Limited

THE INDIA CEMENTS LIMITED UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2010-11 TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AS REQUIRED UNDER SECTION 124 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2013 READ WITH THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AUTHORITY (ACCOUNTING, AUDIT, TRANSFER AND REFUND) RULES, 2016, AS AMENDED FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201040000010433 KUMAR KRISHNA LADE BHILAI 490006 1201060000057278 Bhausaheb Trimbak Pagar Nasik 422005 1201060000138625 Rakesh Dutt Panvel 410206 1201060000175241 JAI KISHAN MOHATA RAIPUR 492001 1201060000288167 G. VINOD KUMAR JAIN MANDYA 571401 1201060000297034 MALLAPPA LAGAMANNA METRI BELGAUM 591317 1201060000309971 VIDYACHAND RAMNARAYAN GILDA LATUR 413512 1201060000326174 LEELA K S UDUPI 576103 1201060000368107 RANA RIZVI MUZAFFARPUR 842001 1201060000372052 S KAILASH JAIN BELLARY 583102 1201060000405315 LAKHAN HIRALAL AGRAWAL JALNA 431203 1201060000437643 SHAKTI SHARAN SHUKLA BHADOHI 221401 1201060000449205 HARENDRASINH LALUBHA RANA LATHI 365430 1201060000460605 PARASHURAMAPPA A SHIMOGA 577201 1201060000466932 SHASHI KAPOOR BHAGALPUR 812001 1201060000472832 SHARAD GANESH KENI RATNAGIRI 415612 1201060000507881 NAYNA KESHAVLAL DAVE NALLASOPARA (E) 401209 1201060000549512 SANDEEP OMPRAKASH NEVATIA MAHAD 402301 1201060000555617 SYED QUAMBER HUSSAIN MUZAFFARPUR 842001 Page 1 of 301 FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201060000567221 PRASHANT RAMRAO KONDEBETTU BELGAUM 591201 1201060000599735 VANDANA MISHRA ALLAHABAD 211016 1201060000630654 SANGITA AGARWAL CUTTACK 753004 1201060000646546 SUBODH T -

Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Pp.280, Edition: 2019 ISBN

HINDI NOVEL Aadikatha(Katha Bharti Series) Rajkamal Chaudhuri Abhiyatri(Assameese novel - A.W) Tr. by Pratibha NirupamaBargohain, Pp. 66, First Edition : 2010 Tr. Dinkar Kumar ISBN 978-81-260-2988-4 Rs. 30 Pp. 124, Edition : 2012 ISBN 978-81-260-2992-1 Rs. 50 Ab Na BasoIh Gaon (Punjabi) Writer & Tr.Kartarsingh Duggal Ab Mujhe Sone Do (A/w Malayalam) Pp. 420, Edition : 1996 P. K. Balkrishnan ISBN: 81-260-0123-2 Rs.200 Tr. by G. Gopinathan Aabhas Pp.180, Rs.140 Edition : 2016 (Award-winning Gujarati Novel ‘Ansar’) ISBN: 978-81-260-5071-0, Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Alp jivi(A/w Telugu) Pp.280, Edition: 2019 Rachkond Vishwanath Shastri ISBN: 978-93-89195-00-2 Rs.300 Tr.Balshauri Reddy Pp 138 Adamkhor(Punjabi) Edition: 1983, Reprint: 2015 Nanak Singh Rs.100 Tr. Krishan Kumar Joshi Pp. 344, Edition : 2010 Amrit Santan(A/W Odia) ISBN: 81-7201-0932-2 Gopinath Mohanti (out of stock) Tr. YugjeetNavalpuri Pp. 820, Edition : 2007 Ashirvad ka Rang ISBN: 81-260-2153-5 Rs.250 (Assameese novel - A.W) Arun Sharma, Tr. Neeta Banerjee Pp. 272, Edition : 2012 Angliyat(A/W Gujrati) ISBN 978-81-260-2997-6 Rs. 140 by Josef Mekwan Tr. Madan Mohan Sharma Aagantuk(Gujarati novel - A.W) Pp. 184, Edition : 2005, 2017 Dhiruben Patel, ISBN: 81-260-1903-4 Rs.150 Tr. Kamlesh Singh Anubhav (Bengali - A.W.) Ankh kikirkari DibyenduPalit (Bengali Novel Chokher Bali) Tr. by Sushil Gupta Rabindranath Tagorc Pp. 124, Edition : 2017 Tr. Hans Kumar Tiwari ISBN 978-81-260-1030-1 Rs. -

J.B.METZLER Metzler Lexikon Weltliteratur

1682 J.B.METZLER Metzler Lexikon Weltliteratur 1000 Autoren von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart Band 1 A-F Herausgegeben von Axel Ruckaberle Verlag J. B. Metzler Stuttgart . Weimar Der Herausgeber Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen National Axel Ruckaberle ist Redakteur bei der Zeitschrift für bibliothek Literatur »TEXT+ KRITIK«, beim >>Kritischen Lexikon Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese zur deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur<< (KLG) und Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; beim >>Kritischen Lexikon zur fremdsprachigen detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über Gegenwartsliteratur<< (KLfG). <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. Rund die Hälfte der in diesen Bänden versammelten Autorenporträts stammen aus den folgenden Lexika: >>Metzler Lexikon englischsprachiger Autorinnen und Autoren<<, herausgegeben von Eberhard Kreutzer und ISBN-13: 978-3-476-02093-2 Ansgar Nünning, 2002/2006. >>Metzler Autoren Lexikon<<, herausgegeben von Bernd Lutz und Benedikt Jeßing, 3. Auflage 2004. ISBN 978-3-476-02094-9 ISBN 978-3-476-00127-6 (eBook) »Metzler Lexikon amerikanischer Autoren<<, heraus DOI 10.1007/978-3-476-00127-6 gegeben von Bernd Engler und Kurt Müller, 2000. »Metzler Autorinnen Lexikon«, herausgegeben von Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheber rechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Ute Hechtfischer, Renate Hof, Inge Stephan und engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Flora Veit-Wild, 1998. Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das >>Metzler Lexikon -

1FH E WORILD BA NIK RJESEARCHI IPROGRAM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

\ oo5 Public Disclosure Authorized 1FH E WORILD BA NIK RJESEARCHI IPROGRAM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ABSTRACTS1 O CURRENT STUIES THE WORLD BANK RESEARCH PROGRAM 1996 Abstracts of Current Studies The World Bank Washington, DC Objectives and Definition of World Bank Research The World Bank's research program has four basic objectives: * To support all aspects of Bank operations, including the assessment of development progress in member countries * To broaden understanding of the development process * To improve the Bank's capacity to give policy advice to its members * To help develop indigenous research capacity in member countries. Research at the Bank encompasses analytical work designed to produce results with wide applica- bility across countries or sectors. Bank research, in contrast to academic research, is directed toward recognized and emerging policy issues and is focused on yielding better policy advice. Although motivated by policy problems, Bank research addresses longer-term concerns rather than the imme- diate needs of a particular Bank lending operation or of a particular country or sector report. Activities classified as research at the Bank do not, therefore, include the economic and sector work and policy analysis carried out by Bank staff to support operations in particular countries. Economic and sector work and policy studies take the product of research and adapt it to specific projects or country settings, whereas Bank research contributes to the intellectual foundations of future lending opera- tions and policy advice. Both activities-research and economic and sector work-are critical to the design of successful projects and effective policy.