The Challenge of Gender Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women-Empowerment a Bibliography

Women’s Studies Resources; 5 Women-Empowerment A Bibliography Complied by Meena Usmani & Akhlaq Ahmed March 2015 CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES 25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market) New Delhi-110 001 Ph. 91-11-32226930, 322266931 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cwds.ac.in/library/library.htm 1 PREFACE The “Women’s Studies Resources Series” is an attempt to highlight the various aspect of our specialized library collection relating to women and development studies. The documents available in the library are in the forms of books and monographs, reports, reprints, conferences Papers/ proceedings, journals/ newsletters and newspaper clippings. The present bibliography on "Women-Empowerment ” especially focuses on women’s political, social or economic aspects. It covers the documents which have empowerment in the title. To highlight these aspects, terms have been categorically given in the Subject Keywords Index. The bibliography covers the documents upto 2014 and contains a total of 1541 entries. It is divided into two parts. The first part contains 800 entries from books, analytics (chapters from the edited books), reports and institutional papers while second part contains over 741 entries from periodicals and newspapers articles. The list of periodicals both Indian and foreign is given as Appendix I. The entries are arranged alphabetically under personal author, corporate body and title as the case may be. For easy and quick retrieval three indexes viz. Author Index containing personal and institutional names, Subject Keywords Index and Geographical Area Index have been provided at the end. We would like to acknowledge the support of our colleagues at Library. -

Bibliography

161 Bibliography Acosta, Pablo, and others (2007). What is the impact of international remit- tances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4249 (June). Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Adams, Richard H., Alfredo Cuecuecha and John M. Page (2008). The impact of remittances on poverty and inequality in Ghana. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4732 (September). Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Adato, Michelle, and Lawrence Haddad (2001). Targeting poverty through community-based public works programs: a cross-disciplinary assessment of recent experience in South Africa. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Discussion Paper, No. 121. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. Addison, Tony (2009). Chronic poverty in the global economy. European Jour- nal of Development Research, vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 174-178. Aizenman, Joshua (2005). Financial liberalization: how well has it worked for developing countries? FRBSF Economic Letter (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), No. 2005-06 (8 April), pp. 1-3. Akroyd, Stephen, and Lawrence Smith (2007). Review of public spending to agriculture: a joint DFID/World Bank study. London: United Kingdom Department for International Development; Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Alam, Asad, and others (2005). Growth, Poverty, and Inequality: Eastern Eu- rope and the Former Soviet Union. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Alderman, Harold, and Victor Lavy (1996). Household responses to public health services: cost and quality trade-offs.World Bank Research Observer, vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 3-22. Amsden, Alice H. (1989). Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industriali- zation. New York: Oxford University Press. -

AFRICAN LITERATURE and the ENVIRONMENT: a STUDY in POSTCOLONIAL ECOCRITICISM By

AFRICAN LITERATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A STUDY IN POSTCOLONIAL ECOCRITICISM By Cajetan N. Iheka A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English – Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT AFRICAN LITERATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A STUDY IN POSTCOLONIAL ECOCRITICISM By Cajetan N. Iheka African Literature and the Environment: A Study in Postcolonial Ecocriticism , examines how African literary texts document, critique, and offer alternative visions on ecological crises such as the Niger-Delta oil pollution and the dumping of toxic wastes in African waters. The study challenges the anthropocentricism dominating African environmental literary scholarship and addresses a gap in mainstream ecocriticism which typically occludes Africa’s environmental problems. While African literary criticism often focuses on impacts of environmental problems on humans, my dissertation, in contrast, explores the entanglements of humans and nonhumans. The study contributes to globalizing ecocriticism, expands the bourgeoning corpus of ecological investigations in African literary criticism, and participates in efforts to foster interdisciplinary connections between the humanities and the sciences. Following the lead of postcolonial ecocritics, like Rob Nixon, who have pressed the need for dialogue between ecocriticism and postcolonialism, Chapter One interprets Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth , Homi Bhabha’s Location of Culture, and Gayatri Spivak’s A Critique of Postcolonial Reason as an -

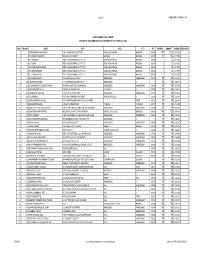

Unclaimed Dividend for 2002-03

1 of 72 ANNEXURE TO FORM 1 INV TANFAC INDUSTRIES LIMITED DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2002-2003 S.NO. FOL NO. NAME ADD1 ADD2 CITY PIN SHARES AMOUNT WARNO REMARKS 1 2 SARASWATHI NARAYANAN C/O L NARAYANAN CHETTIAR VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 101 121.2 2317604 2 4 T N KRISHNA MOORTHI 50 MAHAL 6TH STREET MADURAI MADURAI 625001 11 13.2 2317505 3 9 K R GANESAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317605 4 10 S S MITRA SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317606 5 11 S M THIRUNAVUKARASU SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317607 6 27 K N SUBRAMANIAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317608 7 29 C T RAMANATHAN SREE VISALAKSHI MILLS PVT LTD VISALAKSHI NAGAR MADURAI 625401 1 1.2 2317609 8 112 BACHUBHAI BHATT 19-B PANCHSHIL SOCIETY AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380013 50 60 2305488 9 200 YOGESH BHAVSAR F 12 VARDHMAN NAGAR FLATS AHMEDABAD 0 0 50 60 2320317 10 224 DWARKADAS GOVINDDAS PARIKH RADHIKA CAMP ROAD SHAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380004 50 60 2305098 11 229 KRISHNAMURTHY K A C/O MR K S ADINARAYAN PALAKKAD 0 678003 50 60 2324671 12 232 PADMAKANT DALVADI C/2 SUTIRTH APPARTMENT AHMEDABAD AHMEDABAD 380015 50 60 2305633 13 298 P B SHARMA FLAT NO.4 ADINATH APARTMENT JAM NAGAR (GUJ) 0 361008 50 60 2323801 14 429 GOPALKRISHNA HALIYAL AT PO MOTAVAGHHCHHIPA TAL KILLA PARDI 0 PARDI 396125 50 60 2321186 15 556 SOMASUNDARAM K 2- SOUTH USMAN ROAD T. -

The India Cements Limited

THE INDIA CEMENTS LIMITED UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2010-11 TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AS REQUIRED UNDER SECTION 124 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2013 READ WITH THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AUTHORITY (ACCOUNTING, AUDIT, TRANSFER AND REFUND) RULES, 2016, AS AMENDED FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201040000010433 KUMAR KRISHNA LADE BHILAI 490006 1201060000057278 Bhausaheb Trimbak Pagar Nasik 422005 1201060000138625 Rakesh Dutt Panvel 410206 1201060000175241 JAI KISHAN MOHATA RAIPUR 492001 1201060000288167 G. VINOD KUMAR JAIN MANDYA 571401 1201060000297034 MALLAPPA LAGAMANNA METRI BELGAUM 591317 1201060000309971 VIDYACHAND RAMNARAYAN GILDA LATUR 413512 1201060000326174 LEELA K S UDUPI 576103 1201060000368107 RANA RIZVI MUZAFFARPUR 842001 1201060000372052 S KAILASH JAIN BELLARY 583102 1201060000405315 LAKHAN HIRALAL AGRAWAL JALNA 431203 1201060000437643 SHAKTI SHARAN SHUKLA BHADOHI 221401 1201060000449205 HARENDRASINH LALUBHA RANA LATHI 365430 1201060000460605 PARASHURAMAPPA A SHIMOGA 577201 1201060000466932 SHASHI KAPOOR BHAGALPUR 812001 1201060000472832 SHARAD GANESH KENI RATNAGIRI 415612 1201060000507881 NAYNA KESHAVLAL DAVE NALLASOPARA (E) 401209 1201060000549512 SANDEEP OMPRAKASH NEVATIA MAHAD 402301 1201060000555617 SYED QUAMBER HUSSAIN MUZAFFARPUR 842001 Page 1 of 301 FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201060000567221 PRASHANT RAMRAO KONDEBETTU BELGAUM 591201 1201060000599735 VANDANA MISHRA ALLAHABAD 211016 1201060000630654 SANGITA AGARWAL CUTTACK 753004 1201060000646546 SUBODH T -

Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Pp.280, Edition: 2019 ISBN

HINDI NOVEL Aadikatha(Katha Bharti Series) Rajkamal Chaudhuri Abhiyatri(Assameese novel - A.W) Tr. by Pratibha NirupamaBargohain, Pp. 66, First Edition : 2010 Tr. Dinkar Kumar ISBN 978-81-260-2988-4 Rs. 30 Pp. 124, Edition : 2012 ISBN 978-81-260-2992-1 Rs. 50 Ab Na BasoIh Gaon (Punjabi) Writer & Tr.Kartarsingh Duggal Ab Mujhe Sone Do (A/w Malayalam) Pp. 420, Edition : 1996 P. K. Balkrishnan ISBN: 81-260-0123-2 Rs.200 Tr. by G. Gopinathan Aabhas Pp.180, Rs.140 Edition : 2016 (Award-winning Gujarati Novel ‘Ansar’) ISBN: 978-81-260-5071-0, Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Alp jivi(A/w Telugu) Pp.280, Edition: 2019 Rachkond Vishwanath Shastri ISBN: 978-93-89195-00-2 Rs.300 Tr.Balshauri Reddy Pp 138 Adamkhor(Punjabi) Edition: 1983, Reprint: 2015 Nanak Singh Rs.100 Tr. Krishan Kumar Joshi Pp. 344, Edition : 2010 Amrit Santan(A/W Odia) ISBN: 81-7201-0932-2 Gopinath Mohanti (out of stock) Tr. YugjeetNavalpuri Pp. 820, Edition : 2007 Ashirvad ka Rang ISBN: 81-260-2153-5 Rs.250 (Assameese novel - A.W) Arun Sharma, Tr. Neeta Banerjee Pp. 272, Edition : 2012 Angliyat(A/W Gujrati) ISBN 978-81-260-2997-6 Rs. 140 by Josef Mekwan Tr. Madan Mohan Sharma Aagantuk(Gujarati novel - A.W) Pp. 184, Edition : 2005, 2017 Dhiruben Patel, ISBN: 81-260-1903-4 Rs.150 Tr. Kamlesh Singh Anubhav (Bengali - A.W.) Ankh kikirkari DibyenduPalit (Bengali Novel Chokher Bali) Tr. by Sushil Gupta Rabindranath Tagorc Pp. 124, Edition : 2017 Tr. Hans Kumar Tiwari ISBN 978-81-260-1030-1 Rs. -

1FH E WORILD BA NIK RJESEARCHI IPROGRAM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

\ oo5 Public Disclosure Authorized 1FH E WORILD BA NIK RJESEARCHI IPROGRAM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ABSTRACTS1 O CURRENT STUIES THE WORLD BANK RESEARCH PROGRAM 1996 Abstracts of Current Studies The World Bank Washington, DC Objectives and Definition of World Bank Research The World Bank's research program has four basic objectives: * To support all aspects of Bank operations, including the assessment of development progress in member countries * To broaden understanding of the development process * To improve the Bank's capacity to give policy advice to its members * To help develop indigenous research capacity in member countries. Research at the Bank encompasses analytical work designed to produce results with wide applica- bility across countries or sectors. Bank research, in contrast to academic research, is directed toward recognized and emerging policy issues and is focused on yielding better policy advice. Although motivated by policy problems, Bank research addresses longer-term concerns rather than the imme- diate needs of a particular Bank lending operation or of a particular country or sector report. Activities classified as research at the Bank do not, therefore, include the economic and sector work and policy analysis carried out by Bank staff to support operations in particular countries. Economic and sector work and policy studies take the product of research and adapt it to specific projects or country settings, whereas Bank research contributes to the intellectual foundations of future lending opera- tions and policy advice. Both activities-research and economic and sector work-are critical to the design of successful projects and effective policy. -

ATTENDEES LIST | 28Th IAFFE Annual Conference Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland | 27-29 June 2019

ATTENDEES LIST | 28th IAFFE Annual Conference Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland | 27-29 June 2019 Kristina Abbotts, Taylor & Francis Group (UK) Otgo Banzragch, National University of Mongolia (Mongolia) Tindara Addabbo, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (Italy) Hannah Bargawi, SOAS, University of London (UK) Olanrewaju Adediran, University of the Witwatersrand Freyja Barkardottir, City of reykjavík (Iceland) (South Africa) Yady Barrero Amortegui, Universidad de Antioquia Jumoke Adeyeye, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife (Colombia) (Nigeria) Kripa Basnyat, London School of Economics and Political Bina Agarwal, University of Manchester (India) Science (UK) Ozgun AKDURAN, Political Science Faculty (Turkey) Kathryn Beek, Stellebosch University (South Africa) A Akram-Lodhi, Trent University (Canada) Lourdes Beneria, Cornell University (Spain) SAJA AL ZOUBI, University of Oxford (UK) Gabriella Berloffa, University of Trento (Italy) Randy Albelda, University of Massachusetts-Boston (USA) BERTHONNET, CNRS UNIVERSITE PARIS 7 (France) Chloe Alexander, University of Birmingham (UK) Francesca Bettio, Universita di Siena-Piazza (Italy) Erica Aloe', Università di Roma Sapienza (Italy) Rosemary Boeglin, London School of Economics (UK) Olga Alonso-Villar, University of Vigo (Spain) Myagmarsuren.B, National University of Mongolia (Mongolia) Muzna Alvi, International Food Policy Research Institute (Ifpri) (India) Brenda Boonabaana, Makerere University (Uganda) ALLISON ANDERSON, University of Washington (USA) Sophie Boote, University -

List of Participants As of 30 April 2013

World Economic Forum on India List of Participants As of 30 April 2013 National Capital Region, Gurgaon, India, 6-8 November 2012 Zoher Abdoolcarim Asia Editor Time International Hong Kong SAR Asanga Executive Director Lakshman Kadirgamar Sri Lanka Abeyagoonasekera Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies Anoka Abeyrathne Co-Founder and Volunteer GreentheClimate.org Sri Lanka Reuben Abraham Executive Director, Centre for Emerging Indian School of Business India Markets Solutions Pranav Adani Managing Director, Agro and Oil & Gas Adani Group India Philippe Advani Vice-President, Global Sourcing Network EADS Germany Vineet Agarwal Joint Managing Director Transport Corporation of India India Ltd Bina Agarwal Professor of Development Economics University of Manchester United Kingdom Manoj Kumar Chief Executive Officer, Indian Karuturi Global Limited India Agarwal Operations Nirmal Kumar Director Adhunik Metaliks Limited India Agarwal (AML) Aakarsh Agarwal Director Adhunik Metaliks Limited India (AML) Anup Agarwalla Managing Director B L A Industries Pvt. Ltd India Manish Agrawal Director MSP Steel & Power Ltd India Nisha Agrawal Chief Executive Officer Oxfam India India Saurabh Agrawal Regional Head, Corporate Finance, Standard Chartered Bank India South Asia Montek Singh Deputy Chairman, Planning Ahluwalia Commission, India Richie Ahuja Asia Regional Director Environmental Defense Fund USA Joiel Akilan Executive Director and Chief BBVA India India Representative Satohiro Akimoto General Manager, Global Intelligence, Mitsubishi Corporation Japan Global Strategy and Business Development Vikram K. Akula Social Entrepreneur, India Muhammad Ali Chairman Securities and Exchange Pakistan Commission of Pakistan (SECP) Michael W. Allworth Global Chairman, Cities Centre of KPMG Australia Excellence Shubhendu Amitabh Group Executive President The Aditya Birla Group India World Economic Forum on India 1/16 Manu Anand Chairman and Chief Executive Officer PepsiCo India Holdings Pvt. -

Creating Sustainable Livelihoods Through Group Farming with Bina Agarwal

Creating sustainable livelihoods through group farming with Bina Agarwal This is a written transcription of Professor Stephanie Barrientos’ Podcast interview with Dr Nic Gowland, covering Professor Agarwal’s research on group farming and how it contributes to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). You can find the audio of the interview here: https://soundcloud.com/globaldevinst/gdi-the-sdgs-creating-sustainable-livelihoods- through-group-farming-withbina-agarwal Dr Nic Gowland: [00:00:25] Today, I am delighted to be speaking to Professor Bina Agarwal, Professor of Development, Economics and Environment at the Global Development Institute at The University of Manchester. Bina thank you very much for joining me today. We'll be discussing your research over the last five or 10 years, looking at sustainable livelihoods through group farming in places such as India and Nepal. But before we jump into the research, as ever, I'm keen to understand your journey that took you to this very successful point in your life. You've studied at, or worked at, some of the most esteemed universities in the world - Cambridge, Princeton, Harvard, New York, now Manchester. Picked up many awards along the way, including the Padma Shri, which I understand is India’s equivalent of an OBE, roughly, and also the 2017 International Balzan Prize. You were the second woman from the global south to ever receive this, the first being Mother Teresa. Before all of that, I'm interested in any experiences or inspirations early in life that, kind of, set you on this path towards your passion for global development and social change… Any examples? Professor Bina Agarwal: [00:01:30] Well, you know, the issues of social justice and inequality have always been important to me. -

A Case for Gender Equality

16 ASIA-PACIFIC HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT About the cover Deficits in women’s power and voice are at the heart of gender inequality. The cover design plays on mathematical symbols to depict the relationships between men and women—what they are and what should be. The equality symbol signifies that all people—women, men and those with other gender identities—are inherently valuable and ought to be equal members of the family and society. Other symbols—unequal, less than, greater than, approximately equal—draw attention to the presence of gender gaps, be they in public spaces, at work or in the home. About the separators Folktales and historical accounts provide a peek into society—as it was or can be imagined. Asia-Pacific has a wealth of local stories, ideas and experiences from the past. The chapter separators present a few selected nuggets. A common thread is women’s power and voice, their creativity and capability. Men are protagonists, not adversaries, in the search for equality, which benefits society as a whole. These short narratives complement and contrast with the Report’s data and analysis, providing a lyrical break between chapters. Power, Voice and Rights A Turning Point for Gender Equality in Asia and the Pacific Published for the United Nations Development Programme Copyright © 2010 by the United Nations Development Programme Regional Centre for Asia Pacific, Colombo Office Human Development Report Unit 23 Independence Avenue, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka ISBN: 978-92-1-126286-5 Assigned UN sales number: E.10.III.B.15 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. -

List of Electoral Colleges of Society

Form-XIII Register of Electoral Colleges maintained under Section 18 of the Haryana Registration and Regulation of Societies Act, 2012 (See Rule 12) Register of Electoral Colleges 1 Name of the Society:- MAHARAJA AGRASEN MEDICAL EDUCATION & SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH SOCIETY 2 Registered Office Address:- VPO:AGROHA, Pin Code:- 125 047, Distt:Hisar (Haryana) 3 Date of Registration:- 08.04.1988 (Old), 12.05.2014 (New) 4 Registration Number:- 56 of 1988-89 (Old), HR 012 2014 00687 (New) 5 No. of Electoral Colleges: 200 Register of Electoral Colleges Sr.No. Identity / No. of Sr.No. of Sh./ Smt. Name of the Member Father's Member- Particulars of Members Member in etc. of College Husband's Name ship the in the Electoral No. Electoral Electoral College 1 College No. 1 6 1 Sh. Abhinav Agarwal 887 2 Sh. Abhishek Bansal 975 3 Sh. Ajay Aggarwal 1330 4 Sh. Ajay Aggarwal 1300 5 Sh.Ajay Bansal 37 6 Sh.Ajay Garg 449 1 Sr.No. Identity / No. of Sr.No. of Sh./ Smt. Name of the Member Father's Member- Particulars of Members Member in etc. of College Husband's Name ship the in the Electoral No. Electoral Electoral College 2 College No. 2 7 1 Sh.Ajay Gupta 35 2 Sh.Ajay Gupta 1 3 Sh. Ajay Kokra S/o Late Sh. Gopi Ram 1459 Kokra 4 Sh. Ajay Ku.Gupta 1135 5 Sh. Ajay Kumar Bansal S/o Sh.Om Prakash Bansal 1334 6 Sh. Ajay Kumar S.Gupta 1028 7 Sh. Ajay Kumar Gupta 466 3 College No. 3 6 1 Sh.