Female, Feminine Or Feminist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

Agnès Varda in Californialand

Les Plages d’Agnès. L’ADRC CINÉ-TAMARIS hotographe, cinéaste et aujourd’hui en partenariat avec Partiste plasticienne, Agnès Varda est l’AFCAE plurielle, et ne cesse d’apporter un souffle présentent de liberté, de créativité, dans la vie culturelle française. Après une première collaboration en 2013 à l’occasion de la ressortie des films de Jacques Demy, CINÉ-TAMARIS et l’ADRC proposent une rétrospective de 9 films restaurés dans laquelle Agnès vous invite à (re)découvrir la variété de son travail. AGNÈS VARDA Rétrospective 9 films © christophe vallaux © christophe Cléo de 5 à 7 Sans toit ni loi Agnès Varda in Californialand Un film écrit et réalisé par Un film écrit et réalisé par Agnès Varda Agnès Varda Los Angeles, les plages de Venice et de Santa Monica, on les a connues, Jacques (Demy) et moi, à chacun de nos séjours. Fiction de 90 minutes Fiction de 105 minutes Elles ont été nos décors de vie et de films, dont pour moi, un film hippie et un film triste. Une jetée qui s’élance dans le Pacifique en noir et blanc filmée en couleurs, filmée en 1985 À en été 1961 – visa n° 24.864 visa n° 60.033 au bout du bout de la ruée vers l’Ouest. Des pique-niques à la plage. Des rencontres, les jeunes Harrison Ford et Jim Morrison, Produit par Images : Patrick Blossier les Knop and King et Viva! avec un point d’exclamation comme nom d’artiste. Les Black Panthers. Les peintures murales. Georges de Beauregard Son : Jean-Paul Mugel Images : Jean Rabier Décors : Jean Bauer, Son : Jean Labussière Anne Violet Décors : Bernard Evein Musique : Joanna Bruzdowicz -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 229-258 Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre By Perla Carrillo Quiroga This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the travelogue genre while drawing a parallel with a Bazanian teleology of cinematic realism. On the other, it incorporates phenomenological approaches with neuroscience’s discovery of mirror neurons and an embodied simulation mechanism in order to reflect upon the techniques and cinematic styles of the travelogue genre. In this article I discuss the travelogue film genre through a phenomenological approach to film studies. First I trace the history of the travelogue film by distinguishing three main categories, each one ascribed to a particular form of realism. The hyper-realistic travelogue, which is related to a perceptual form of realism; the first person travelogue, associated with realism as authenticity; and the travelogue as a traditional documentary which is related to a factual form of realism. I then discuss how these categories relate to Andre Bazin’s ideas on realism through notions such as montage, duration, the long take and his "myth of total cinema". I discuss the concept of perceptual realism as a key style in the travelogue genre evident in the use of extra-filmic technologies which have attempted to bring the spectator’s body closer into an immersion into filmic space by simulating the physical and sensorial experience of travelling. -

Representing History and the Filmmaker in the Frame

REPRESENTING HISTORY AND THE FILMMAKER IN THE FRAME Trent Griffiths* Resumo: A presença do realizador no enquadramento representa uma relação única entre o documentário e a História em que o realizador se envolve na história social através da sua experiência pessoal e enquanto autor de uma representação. O realizador no enquadramento é, também, um representante do momento histórico, ao explorar de modo reflexivo o encontro com o processo de mediação e auto-representação que caracteriza a sociedade pós-moderna. Palavras-chave: subjetividade, auto-reflexividade, realizador no enquadramento. Resumen: La presencia del director en el encuadre representa una relación úni- ca entre el documental y la historia, en la cual el director se involucra en la historia social a través de su experiencia personal como autor de una representación. El director en el encuadre es también un representante del momento histórico, al explorar de modo reflexivo el encuentro con el proceso de mediación y auto-representación que caracteriza a la sociedad posmoderna. Palabras clave: subjetividad, auto-reflexividad, director en el encuadre. Abstract: The presence of the filmmaker as a subject in the documentary frame represents a unique relationship between documentary film and history, where the filmmaker engages with social history through their personal experience of authoring a representation of it. This paper explores how the tension between the filmmaker’s presence as an author and as a subject enacts a kind of self-reflexivity that recasts the possibilities of representing history through documentary film. Keywords: Subjectivity, self-reflexivity, filmmaker in the frame. Résumé: La présence du réalisateur dans l’image cinématographique témoigne d’une relation unique entre documentaire et histoire : le réalisateur s’engage dans l’his- toire sociale à travers d’une expérience personnelle et comme auteur d’une représen- tation. -

Proquest Dissertations

Filming in the Feminine Plural: The Ethnochoranic Narratives of Agnes Varda Lindsay Peters A Thesis in The Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2010 © Lindsay Peters, 2010 Library and Archives Bib!ioth6que et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-71098-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-71098-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

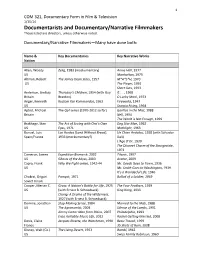

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

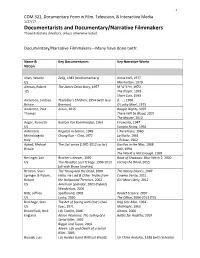

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Who's Afraid of Agnes Varda?

EDITORIAL By Elisabeth O. Sjaastad Masculine - Feminine 2010 will go down in film history on account of Kathryn Bigelow. She became the first woman to win the Academy Award for best director and best film. Yet much to the dismay of many, the Cannes film festival didn’t find a single film directed by a woman worthy of competing for the Palme d’Or this year. Regardless of whether those films simply weren’t as good as the one’s that did get selected, the situation does raise the issue of the small number of films directed by women globally. Today women seem to have no trouble getting into highly competitive film schools, but after they graduate many of them struggle more to establish themselves than their male colleagues. Several countries are now trying to redress this gender imbalance. During this year’s Cannes festival one of the most innovative directors in European film, Agnès Varda, was awarded the “Carosse d’or” by FERA member SRF. FERA joins our French members in celebrating the exceptional work of Agnès Varda, the “grandmother” of the French New Wave. The films of Agnès Varda are legally available on www.theauteurs.com . Who’s afraid of Agnès Varda? In 1954 26 year old Agnès Varda decided to make a film. She had no film training or experience. The film La Pointe Courte proved to be a watershed in modern film history and the precursor to the French new wave. Agnès Varda has made some of the most innovative and thought-provoking films in the last 50 years. -

Cinema Comparat/Ive Cinema

CINEMA COMPARAT/IVE CINEMA VOLUME IV · No.8 · 2016 Editors: Gonzalo de Lucas (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and Albert Elduque (University of Reading). Associate Editors: Ana Aitana Fernández (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Núria Bou (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Xavier Pérez (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Advisory Board: Dudley Andrew (Yale University, United States), Jordi Balló (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain), Raymond Bellour (Université Sorbonne-Paris III, France), Francisco Javier Benavente (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Nicole Brenez (Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne, France), Maeve Connolly (Dun Laoghaire Institut of Art, Design and Technology, Irleland), Thomas Elsaesser (University of Amsterdam, Netherlands), Gino Frezza (Università de Salerno, Italy), Chris Fujiwara (Edinburgh International Film Festival, United Kingdom), Jane Gaines (Columbia University, United States), Haden Guest (Harvard University, United States), Tom Gunning (University of Chicago, United States), John MacKay (Yale University, United States), Adrian Martin (Monash University, Australia), Cezar Migliorin (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil), Alejandro Montiel (Universitat de València), Meaghan Morris (University of Sidney, Australia and Lignan University, Hong Kong), Raffaelle Pinto (Universitat de Barcelona), Ivan Pintor (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Àngel Quintana (Universitat de Girona, Spain), Joan Ramon Resina (Stanford University, United States), Eduardo A.Russo (Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina), Glòria Salvadó (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Yuri -

Jan – Mar 2018 V11

Jan – Mar 2018 V11 ∙ 3 MEMBERSHIP “Forward-looking communities strive to hold onto important parts of their past and, if practical, make sensible renovations to bring venerable structures into the future. That’s the case with the newly restored Dundee Theater.” — Omaha World-Herald Editorial, Nov 31, 2017 December was a dream. On the first day of the month, we opened the doors of the renovated Dundee Theater, and, along with our café partners Kitchen Table Members Select Central, welcomed thousands of you back to Omaha’s historic cinema. Thanks to Your voices have been heard! This year’s Members Select winner was described the generosity and efforts of so many, we reached our goal to have the project by Roger Ebert as “a movie with the courage to be about complex, sweeping completed in time to host the Omaha premiere of Film Streams Board Member emotions, and to use the star power of its actors without apology.” Alexander Payne’s latest opus, Downsizing (still showing!). And we’re just getting started. This quarter will bring outstanding new releases from around the world to both of our cinemas, along with annual traditions like Jan 5 – 11 Ruth Sokolof the Oscar Shorts and Film Streams Members Select, our first repertory series (and Courses!) in the Dundee Theater’s Linder Microcinema, and a much- Out of Africa requested return of Midnight Movies to the Dundee. Dir. Sydney Pollack — 1985 — USA 161 min — PG So, join us! The show is just getting started. Meryl Streep, Robert Redford, and cinematographer David Watkin’s sweeping images of the Kenyan plains light up the screen in this sultry drama. -

Jacquot De Nantes

Jacquot de Nantes de Agnès Varda FFICHE FILM Fiche technique France - 1991 - 2h - Couleur et N. & B. Réalisateur : Agnès Varda Scénario : Agnès Varda d’après les souvenirs de Jacques Demy Musique : Joanna Bruzdowicz et 20 chansons d’époque Interprètes : Philippe Maron (Jacquot 1) Edouard Joubeaud (Jacquot 2) Résumé Laurent Monnier (Jacquot 3) Brigitte de Villepoix Le petit Jacques Demy a de la chance : sa passion pour le cinéma. Non content de (Marilou) prime enfance, dans les années trente, est fréquenter la salle la plus proche avec une marquée du sceau de l’insouciance et du assiduité qui ne se dément pas, le jeune Daniel Dublet bonheur. Son père, garagiste, sa mère et homme entreprend de faire lui-même (Raymond) son petit frère l’entourent de toute l’affec- quelques essais en 8 mm. Son père, qui Clément Delaroche tion dont on peut rêver. Et rêver, justement, juge cette passion quelque peu déplacée, Jacquot aime cela. Rien ne l’attire davan- lui fait étudier la mécanique. Mais l’obsti- (Yvon 1) tage que le théâtre de marionnettes qui nation de Jacques a raison de cette résis- Rody Averty permet à son imagination de vagabonder. tance somme toute compréhensible. Alors (Yvon 2) La guerre ne modifie pas réellement cette que la guerre a pris fin et que la vie a peu à prédisposition au bonheur, même si les peu repris ses droits, le jeune garçon brûle Hélène Pors bombardements de 1943 lui inculquent un comme jamais de devenir cinéaste : il (Reine 1, la petite voisine) dégoût durable pour la violence. Son atti- convainc son père de le laisser partir pour rance pour le théâtre se mue peu à peu en Paris..