Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-One, 2014 Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Luftwaffe Wasn't Alone

PIONEER JETS OF WORLD WAR II THE LUFTWAFFE WASN’T ALONE BY BARRETT TILLMAN he history of technology is replete with Heinkel, which absorbed some Junkers engineers. Each fac tory a concept called “multiple independent opted for axial compressors. Ohain and Whittle, however, discovery.” Examples are the incandes- independently pursued centrifugal designs, and both encoun- cent lightbulb by the American inventor tered problems, even though both were ultimately successful. Thomas Edison and the British inventor Ohain's design powered the Heinkel He 178, the world's first Joseph Swan in 1879, and the computer by jet airplane, flown in August 1939. Whittle, less successful in Briton Alan Turing and Polish-American finding industrial support, did not fly his own engine until Emil Post in 1936. May 1941, when it powered Britain's first jet airplane: the TDuring the 1930s, on opposite sides of the English Chan- Gloster E.28/39. Even so, he could not manufacture his sub- nel, two gifted aviation designers worked toward the same sequent designs, which the Air Ministry handed off to Rover, goal. Royal Air Force (RAF) Pilot Officer Frank Whittle, a a car company, and subsequently to another auto and piston 23-year-old prodigy, envisioned a gas-turbine engine that aero-engine manufacturer: Rolls-Royce. might surpass the most powerful piston designs, and patented Ohain’s work detoured in 1942 with a dead-end diagonal his idea in 1930. centrifugal compressor. As Dr. Hallion notes, however, “Whit- Slightly later, after flying gliders and tle’s designs greatly influenced American savoring their smooth, vibration-free “Axial-flow engines turbojet development—a General Electric– flight, German physicist Hans von Ohain— were more difficult built derivative of a Whittle design powered who had earned a doctorate in 1935— to perfect but America's first jet airplane, the Bell XP-59A became intrigued with a propeller-less gas- produced more Airacomet, in October 1942. -

Read Book # World War II Jet Aircraft of Germany: V-1

IZGMSHR0AW2L eBook // World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel... W orld W ar II jet aircraft of Germany: V -1, Messersch mitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, A rado A r 234, Focke-W ulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 Filesize: 8.19 MB Reviews This ebook is great. I really could comprehended every thing using this composed e ebook. Its been designed in an exceedingly simple way and it is only following i finished reading this publication where basically modified me, modify the way in my opinion. (Herminia Blanda) DISCLAIMER | DMCA BN6TSLX9Q92P / eBook \ World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel... WORLD WAR II JET AIRCRAFT OF GERMANY: V-1, MESSERSCHMITT ME 262, HEINKEL HE 162, HORTEN HO 229, ARADO AR 234, FOCKE-WULF TA 183, HEINKEL HE 280 To download World War II jet aircra of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 PDF, please follow the hyperlink below and download the document or get access to other information that are highly relevant to WORLD WAR II JET AIRCRAFT OF GERMANY: V-1, MESSERSCHMITT ME 262, HEINKEL HE 162, HORTEN HO 229, ARADO AR 234, FOCKE-WULF TA 183, HEINKEL HE 280 book. Books LLC, Wiki Series, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from the UK. No. book. Read World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 Online Download PDF World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 Download ePUB World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 ZZ9D0KF7ISAA // Kindle # World War II jet aircraft of Germany: V-1, Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel.. -

Horten Ho 229 V3 All Wood Short Kit

Horten Ho 229 V3 All Wood Short Kit a Radio Controlled Model in 1/8 Scale Design by Gary Hethcoat Copyright 2007 Aviation Research P.O. Box 9192, San Jose, CA 95157 http://www.wingsontheweb.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 408-660-0943 Table of Contents 1 General Building Notes ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Getting Help .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Laser Cut Parts .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Electronics ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Building Options ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.4.1 Removable Outer Wing Panels .............................................................................................. 4 1.4.2 Drag Rudders ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.4.3 Retracts .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.4.4 Frise Style Elevons ............................................................................................................... -

The History of the 445Th Bombardment Group (H) (Unofficial) Rudolph J

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl World War Regimental Histories World War Collections 1947 The history of the 445th Bombardment Group (H) (unofficial) Rudolph J. Birsic Follow this and additional works at: http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his Recommended Citation Birsic, Rudolph J., "The history of the 445th Bombardment Group (H) (unofficial)" (1947). World War Regimental Histories. 98. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World War Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in World War Regimental Histories by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE _445TH BOMBARDMENT GROUP (H) (UNOFFICIAL) tl ~ ... ~ ~ ~ . ., _, .. STATIONED OVERSEAS AT TIBENHAM NORFOLK, ENGLAND IN THE 2ND COMBAT WING, 2ND AIR DIVISION, OF THE 8TH AIR FORCE !._., f f f BY RUDOLPH J, BIRSIC ..... .. .... .. .. : ! ,, . .. .. -. '•. :. :::. .. ..: ... ... ;,, ... ·~.. .. .. .., . "< .... ... _ .... ... .. · . .. ,< , . .. < ... ...... .. .. : ' ..(. ~ . • t• • .. .. ' .' .. .. ' '.,;• ...... .l . .. ... , .. .. ._..·,._ . •' ... .. ' ... .... TABLE ·OF CONTENTS Foreword Dedication I April 1, 1943 through December 12, 1943 II December 13, 1943 through June 5, 1944 III June 6, 1944 through December 31, 1944 IV January 1, 1945 through September 12, 194'5 V Awards and Decorations VI Group Character VII The Group Bombing Record VIII Photographs Additions to Roster Acknowledgment ~ FOREW~ORD No book this size could ever hope to record completely, day by day, mis sion by mission, the history of the 445th Bombardment Group. Since various limitations did exist and handicap the publication of our Group History, the only alternative was to select such material as would most emphatically demonstrate how superior our Group really was. -

December 2019

CLUB H.C.R.F. Calendar 2019/20 INFO Our fixed flying times are every Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday morning Web Site Date Day Event Where/When www.hcrf.co.nz 2 Dec Mon Club Night Pinewoods Hall 7.30 pm 23 Marie Ave 7 Dec Sat Winch Gliding Wainui 8.30 am - 12.00 noon Contacts 11 Dec Wed Christmas Wainui 5.00 pm Twilight President 4 Jan Sat Winch Gliding Wainui 8.30 am - 12.00 noon Peter Denison 29 Jan Wed Twilight 3 Wainui 5-00 pm [email protected] (09) 426-2455 1 Feb Sat Winch Gliding Wainui 8.30 am - 12.00 noon 3 Feb Mon Club Night Pinewoods Hall 7.30 pm 23 Marie Ave Secretary/Treasurer 5 Feb Wed Twilight 3 Rain Wainui 5-00 pm Henny Remkes Date [email protected] 027 441-1484 Club Captain Nigel Grace [email protected] 027 420 3182 From the Editor’s Desk Frequency Officer I have been thinking and I think the Jim Hall position of Weather Witch should be an Executive Position, and as [email protected] such should be voted on at the (09) 426-1478 AGM. This would save all the bad starts we had with the weather for Editor the first few twilights. Is this a good Ross McDonnell idea? [email protected] 021 216-0702 COVER PHOTO The youngest and oldest members of the Above is a suggested sign for the club, Evan Ford and field. Senior Instructor Jim Hall. Great to see y’all at the first twilight Seen here with of the summer. -

Aerodynamic Optimization for Low Reynolds Number Flight of a Solar Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2008 Aerodynamic optimization for low Reynolds number flight of a solar unmanned aerial vehicle Louis Dube University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Dube, Louis, "Aerodynamic optimization for low Reynolds number flight of a solar unmanned aerial vehicle" (2008). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2398. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/ziey-32pi This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AERODYNAMIC OPTIMIZATION FOR LOW REYNOLDS NUMBER FLIGHT OF A SOLAR UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLE by Louis Dube Bachelor of Science University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree in Aerospace Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering Howard R. Hughes College of Engineering Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2008 UMI Number: 1463501 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

World War II Glider Assault Tactics

World War II Glider Assault Tactics GORDON L. ROTTMAN ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com &-*5&t World War II Glider Assault Tactics GORDON L. ROTTMAN ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Martin Windrow © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 0WFSWJFX 0SJHJOT *OJUJBM(FSNBOPQFSBUJPOT o THE GLIDERS 8 .JMJUBSZHMJEFSDIBSBDUFSJTUJDTDPOTUSVDUJPOoBDDFTToQJMPUTDPOUSPMToTQFFET (MJEFSGMZJOHUBLFPGGoUPXJOHBOEUPXSPQFToJOUFSDPNNVOJDBUJPOoSFMFBTF (MJEFSMBOEJOHTSPVUFToMBOEJOH[POFToPCTUBDMFToEFCBSLJOH 1BSBUSPPQT GLIDER TYPES 17 "NFSJDBO8BDP$(" 8BDP$(" #SJUJTI(FOFSBM"JSDSBGU)PUTQVS.L** "JSTQFFE)PSTB.LT*** (FOFSBM"JSDSBGU)BNJMDBS.L* (FSNBO%'4 (PUIB(P .FTTFSTDINJUU.F TUG AIRCRAFT 27 %JGGJDVMUJFTPGHMJEFSUPXJOH $PNNPOBJSDSBGUUZQFT 5VHVOJUT"NFSJDBOo#SJUJTIo(FSNBO GLIDER PILOTS 30 3FDSVJUNFOUBOEUSBJOJOH"NFSJDBOo#SJUJTIo(FSNBO (MJEFSQJMPUTJOHSPVOEDPNCBU (MJEFSQJMPUJOTJHOJB GLIDER-DELIVERED UNITS 36 $IBSBDUFS 0SHBOJ[BUJPOBOEVOJGPSNT "NFSJDBOo#SJUJTIo(FSNBO 8FBQPOTBSUJMMFSZ "JSCPSOFMJHIUUBOLT GLIDER OPERATIONS 47 5BDUJDBMPWFSWJFX 4VNNBSZPG"MMJFEPQFSBUJPOT4JDJMZ +VMZo#VSNB .BSDIo"VHVTUo /PSNBOEZ +VOFo4PVUIFSO'SBODF "VHVTUo/FUIFSMBOET 4FQUFNCFSo(FSNBOZ .BSDI 4NBMM64PQFSBUJPOT o 4VNNBSZPG(FSNBOPQFSBUJPOT#FMHJVN .BZo(SFFDF "QSJMo$SFUF .BZo3VTTJB +BOVBSZo.BZo*UBMZ 4FQUFNCFSo:VHPTMBWJB .BZo'SBODF +VMZo)VOHBSZ 'FCSVBSZ ASSESSMENT 59 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 62 INDEX 64 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com WORLD WAR II GLIDER ASSAULT TACTICS INTRODUCTION 5IFUXPNBODSFXPGB(PUIB(P -

World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162

QQQDTFM4FFYQ # Book « World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162,... W orld W ar Ii German Jet A ircraft: Messersch mitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, A rado A r 234, Focke-W ulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 Filesize: 2.67 MB Reviews Simply no phrases to clarify. It is really basic but surprises from the 50 percent of the ebook. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Mr. Noah Cummerata IV) DISCLAIMER | DMCA JZU684REIM86 Book // World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162,... WORLD WAR II GERMAN JET AIRCRAFT: MESSERSCHMITT ME 262, HEINKEL HE 162, HORTEN HO 229, ARADO AR 234, FOCKE-WULF TA 183, HEINKEL HE 280 Books LLC, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from the UK. No. book. Read World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke- Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 Online Download PDF World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162, Horten Ho 229, Arado Ar 234, Focke-Wulf Ta 183, Heinkel He 280 0Y6HV3POE9FF // Doc ~ World War Ii German Jet Aircraft: Messerschmitt Me 262, Heinkel He 162,... Oth er eBooks Books for Kindergarteners: 2016 Children's Books (Bedtime Stories for Kids) (Free Animal Coloring Pictures for Kids) 2015. PAP. Book Condition: New. New Book. Delivered from our US warehouse in 10 to 14 business days. -

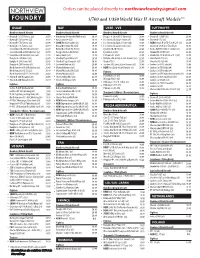

Northview Foundry Catalog A

NORTHVIEW Orders can be placed directly to: [email protected] FOUNDRY 1/700 and 1/350 World War II Aircraft Models** USAAF RAF USSR - VVS LUFTWAFFE Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft Bombers/Attack Aircraft * Boeing B-17C/D Fortress (x2) 20.99 * Armstrong Whitworth Whitley (x3) 20.99 Douglas A-20 w/MV-3 Turret (x3) 20.49 * Dornier D-17M/P (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17E Fortress (x2) 20.99 * Avro Lancaster (x2) 20.99 * Il-2 Sturmovik Single-Seater (x4) 19.49 * Dornier D-17Z (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17F Fortress (x2) 20.99 * SOON Bristol Beaufort (x3) 20.49 * Il-2 Sturmovik Early 2-Seater (x4) 19.49 * NEW Dornier D-217E-5 w/Hs 293 (x3) 20.49 * Boeing B-17G Fortress (x2) 20.99 Bristol Blenheim Mk.I (x3) 19.49 * Il-2 Sturmovik Late2-Seater (x4) 19.49 Dornier D-217K-2 w/Fritz X (x3) 20.49 Consolidated B-24D Liberator (x2) 20.99 Bristol Blenheim Mk.IV (x3) 19.49 Ilyushin DB-3B/3T (x3) 20.49 * Focke-Wulf Fw 200C-4 Condor (x2) 20.99 ConsolidatedB-24 H/J Liberator (x2) 20.99 Douglas Boston Mk.III (x3) 20.49 Ilyushin IL-4 (x3) 20.49 Heinkel He 111E/F (x3) 20.49 * Consolidated B-32 Dominator (x2) 22.99 * Fairey Battle (x3) 19.49 Petlyakov Pe-2(x3) 20.49 * Heinkel He 111H-20/22 w/V-1 (x3) 20.49 Douglas A-20B Havoc (x3) 20.49 * Handley Page Halifax (x2) 20.99 * Petlyakov Pe-8 Early & Late Variants (x2) 22.99 * Henschel Hs 123 (x4) 19.49 Douglas A-20G Havoc (x3) 20.49 * Handley Page Hampden (x3) 20.49 Tupolev TB-3 22.99 Henschel Hs 129 (x4) 19.49 Douglas A-26B Invader (x3) 20.49 * Lockheed Hudson (x3) 20.49 * Tupolev -

Box Nr. Marke Name Maßstab ID G a 1 Bego GERMAN Okw.K1 KÜBELWAGEN TYPE82 1:35 B35-001 G a 2 ACADEMY U.S

Box Nr. Marke Name Maßstab ID G_A 1 Bego GERMAN Okw.K1 KÜBELWAGEN TYPE82 1:35 B35-001 G_A 2 ACADEMY U.S. Tank Transporter DRAGON WAGON 1:72 13409 G_A 3 AIRFIX WWI MALE TANK 1:76 A01375 G_A 4 AIRFIX British 105mm LIGHT FIELD GUN 1:76 A02332 G_A 5 AIRFIX MATILDA "HEDGEHOG" 1:76 A02335 G_A 6 AIRFIX 75mm ASSAUKT GUN STURMGESCHUTZ III 1:76 01306 G_A 7 ITALERI LEOPARD 1 A4 1:72 No 7002 G_A 8 ITALERI MERKAVA I 1:72 No 7005 G_A 9 ITALERI T-62 MAIN BATTLE TANK 1:72 No 7006 G_A 10 ITALERI M1 Abrams 1:72 No 7001 G_A 11 ACADEMY Gournd Vehicle Series-10 U.S. M977 8x8 CARGO TRUCK1:72 13412 G_A 12 ITALERI JS-2 Stalin 1:72 No 77040 G_A 13 AIRFIX CHURCHILL BRIDGE LAYER 1:76 A04301 G_A 14 DRAGON Sd. Kfz. 171 PANTHER G 1:72 7252 G_A 15 TRUMPETER Strv103 c MBT 1:72 07220 G_A 16 UM Antiaircrafttank Sd. Kfz. 140 1:72 348 G_A 17 Revell LEOPARD 2 A5 KWS 1:72 03105 G_A 18 FUJIMI British Infantry Tank VALENTINE 1:76 76007 G_A 19 Hasegawa Mercedes Benz G4/W31 1:72 31128 G_A 20 DRAGON Sd. Kfz. StuG IV EARLY 1:72 7235 G_A 21 Hasegawa 88mm GUN FLAK 18 1:72 31110 G_A 22 TRUMPETER CA-30 Truck 1:72 01103 G_A 23 Revell Sherman Firefly 1:76 03211 G_A 24 ZVEZDA Soviet 122mm HOWITZER 1:72 6122 G_B 25 Revell Sd.Kfz. 251/1 Ausf.C 1:72 03173 G_B 26 Revell Main Battle Tank LEOPARD 2 A4 1:72 03103 G_B 27 Revell Cromwell Mk. -

Aerodynamic Design Considerations and Shape Optimization of Flying Wings in Transonic Flight

12th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conference and 14th AIAA/ISSM AIAA 2012-5402 17 - 19 September 2012, Indianapolis, Indiana Aerodynamic Design Considerations and Shape Optimization of Flying Wings in Transonic Flight M. Zhang1, A. Rizzi1, P. Meng1, R. Nangia2, R. Amiree3 and O. Amoignon3 1Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), 10044 Stockholm, Sweden 2Nangia Aero Research Associates, Bristol BS8 1QU, UK 3Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI), 16490 Stockholm, Sweden This paper provides a technique that minimize the cruise drag (or maximize L/D) for a blended wing body transport with a number of constraints. The wing shape design is done by splitting the problem into 2D airfoil design and 3D twist optimization with a frozen planform. A 45% to 50% reduction of inviscid drag is finally obtained, with desired pitching moment. The results indicate that further improvement can be obtained by modifying the planform and varying the camber more aggressively. I. Introduction & Overview Historically, the flying wing aircraft concept dates as far back as to 1910, when Hugo Junkers believed the flying wing's potentially large internal volume and low drag made it capable of carrying a reasonable amount of payload efficiently over a large distance. In the 30's and 40's the flying wing concept was studied extensively and a series of designs were tried out, with the Horten Ho 229 fighter being the most famous one (Fig 1). Currently, a Blended Wing Body configuration is being investigated by NASA and its industry partners, which incorporates both a flying wing and and the features of conventional transport aircraft (Fig 2). -

O Messerschmitt Me 262 Um Novo Paradigma Na Guerra Aérea

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS O MESSERSCHMITT ME 262 UM NOVO PARADIGMA NA GUERRA AÉREA (1944-1945) NORBERTO ANTÓNIO BIGARES DE MELO ALVES MARTINS Tese orientada pelo Professor Doutor António Ventura e co-orientada pelo Professor Doutor José Varandas, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em HISTÓRIA MILITAR. 2016 «Le vent se lève!...il faut tenter de vivre!» Paul Valéry, Le cimetière marin, 1920. ÍNDICE RESUMO/ABSTRACT 3 PALAVRAS-CHAVE/KEYWORDS 5 AGRADECIMENTOS 6 ABREVIATURAS 7 O SISTEMA DE DESIGNAÇÃO DO RLM 8 A ESTRUTURA OPERACIONAL DA LUFTWAFFE 11 INTRODUÇÃO 12 1. O estado da arte 22 CAPÍTULO I Conceito, forma e produção 27 1. Criação do Me 262 27 2. Interferência de Hitler no desenvolvimento do Me 262 38 3. Produção do Me 262 42 4. Variantes do Me 262 45 CAPÍTULO II A guerra aérea: novas possibilidades 61 1. O Me 262 como caça intercetor 61 2. O Me 262 como caça-bombardeiro 75 3. O Me 262 como caça noturno 83 4. O Me 262 como avião de reconhecimento 85 5. O Me 262 no РОА/ROA (Exército Russo de Libertação) 89 6. Novas táticas 91 1 7. Novo armamento 96 8. O fator humano 100 CAPÍTULO III O legado do Me 262 104 1. Influência na aerodinâmica 104 2. Inovações 107 3. Variantes estrangeiras do Me 262 109 4. Influência do Me 262 em aviões estrangeiros 119 CONCLUSÃO 130 O Me 262 no espaço aéreo: um novo paradigma 132 BIBLIOGRAFIA 136 ANEXOS 144 2 RESUMO A Segunda Guerra Mundial foi, para além de um evento decisivo na transformação do Mundo, palco de imensos desenvolvimentos técnologicos cuja influência se estende até hoje, fazendo parte, inclusive, do dia a dia de milhões de pessoas.