Legal Clinics and Professional Skills Development in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGERIA: Defending Human Rights: Not Everywhere Not Every Right International Fact-Finding Mission Report

NIGERIA: Defending Human Rights: Not Everywhere Not Every Right International Fact-Finding Mission Report April 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms Introduction 1. Delegation’s composition and objectives 3 2. Methodology 3 3. Acknowledgements 4 Summary of key findings 4 I. Historical, economic, geo-political and institutional background 1. Historical overview 5 2. Nigeria’s historical track of human rights: a difficult environment for human rights defenders 6 II. Nigeria and its international and regional commitments 8 III. Constitutional and legislative framework relevant to human rights activities 1. Freedom of Association 10 2. Freedom of Peaceful Assembly 12 3. Right to a Fair Trial and Effective Remedy 13 4. Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Media 13 5. Access to Information 15 IV. Domestic oversight mechanisms 1. The National Human Rights Commission 17 2. The Directorate for Citizen’s Rights 18 3. The Human Rights Desks at police stations 19 4. The Police Service Commission and the Public Complaints Commission 19 V. Groups of human rights defenders at particular risk 1. Defenders operating in the Niger Delta 20 2. Defenders working on corruption and good governance 22 3. Media practitioners 23 4. LGBT defenders 23 Source: European Commission website, http://ec.europa.eu/world/where/nigeria/index fr.htm 5. Women Human Rights Defenders 25 6. Trade unions and labour activists 26 VI. Conclusion and Recommendations 28 Annex 1 List of organisations and institutions met during the fact finding mission 32 This report has been produced with the support of the European Union, the International Organisation of the Francophonie and the Republic and Canton of Geneva. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

2021 Phd Onafuwa.Pdf

SOCIO-LEGAL BARRIERS TO THE EXPANSION OF LEGAL AID IN NIGERIA: INITIATING LEGAL REFORM THROUGH THE CUSTOMARY COURT SYSTEM OLÚBÙNMI EUNICE ỌNÀFUWÀ Doctor of Philosophy School of Business and Law UNIVERSITY OF EAST LONDON July 2020 i Abstract The core of this study is directed towards an analysis of the laws, rules and guidelines that embody legal aid provision in present day Nigeria. This study will employ a socio-legal approach to investigate the root causes of Nigeria’s limited legal aid scheme. It will also focus on the relationship between law and society and will employ appropriate empirical research methods for an in-depth understanding of significant causal factors that influence legal aid provision in Nigeria. These factors will include an examination of Nigerian legal institutions, legal processes, and legal behaviour,1 particularly how legal institutions and legal processes affect individuals and how they are perceived by ordinary citizens and potential recipients of legal aid. This research considers the potential for other sources of law, and other legal institutions, such as customary legal systems, to be used as an additional, credible way to access, develop and expand legal aid provision in Nigeria. This study adopts two qualitative techniques: semi-structured telephone interviews and self- administered questionnaires, which were completed and returned via email. The request for respondents was launched on social media. In total, fifteen respondents partook in the study: twelve via self-administered questionnaires and three via telephone interviews. The inquiry was focused on a people’s perspective, the respondents were a variety of ages above 18, and evenly distributed by gender. -

Reducing the Excessive Use of Pretrial Detention

A publication of the Open Society Justice Initiative, Spring 2008 Contents Foreword Mark Shaw 1 Pretrial Detention Overview Grand Ambitions, Modest Scale 4 In 2006, an estimated 7.4 million people around Todd Foglesong the world were held in detention while awaiting The Scale and Consequences of Pretrial Detention around the World 11 trial—a practice that violates international norms, Martin Schönteich wastes public resources, undermines the rule of Case Studies law, and endangers public health. This issue of Boomerang: Seeking to Reform 44 looks at the global over-reliance Pretrial Detention Practices in Chile Justice Initiatives Verónica Venegas and Luis Vial on pretrial detention and examines the challenges Catalyst for Change: 57 of reducing and reforming its use. The Effect of Prison Visits on Pretrial Detention in India R.K. Saxena On the Front Lines: Insights from 70 FOREWORD Malawi’s Paralegal Advisory Service Clifford Msiska Building and Sustaining Change: 86 Reducing the Excessive Pretrial Detention Reform in Nigeria Anthony Nwapa Use of Pretrial Detention Ebb Tide: The Russian Reforms 103 Mark Shaw of 2001 and Their Reversal Olga Schwartz The broad international consensus favors reducing the use of Frustrated Potential: The Short 121 pretrial detention and, whenever possible, encouraging the and Long Term Impact of Pretrial use of alternative measures, such as release on bail or person- Services in South Africa al recognizance. The aversion to pretrial detention is based Louise Ehlers on a cornerstone of the international human rights regime: Pathway to Justice: 141 the presumption of innocence afforded to persons accused Juvenile Detention Reform of committing a crime.1 International treaties and standards in the United States require policymakers to limit the use of pretrial detention. -

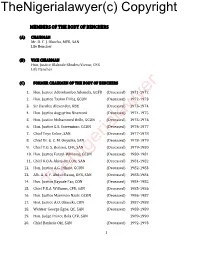

Thenigerialawyer(C) Copyright

TheNigerialawyer(c) Copyright MEMBERS OF THE BODY OF BENCHERS (A) CHAIRMAN Mr. O. C. J. Okocha, MFR, SAN Life Bencher (B) VICE CHIARMAN Hon. Justice Olabode Rhodes-Vivour, CFR Life Bencher (C) FORMER CHAIRMEN OF THE BODY OF BENCHERS 1. Hon. Justice Adetokumbo Ademola, GCFR (Deceased) 1971-1972 2. Hon. Justice Taslim Ellias, GCON (Deceased) 1972-1973 3. Sir Darnley Alexender, KBE (Deceased) 1973-1974 4. Hon. Justice Augustine Nnamani (Deceased) 1974-1975 5. Hon. Justice Mohammed Bello, GCON (Deceased) 1975-1976 6. Hon. Justice G.S. Sowemimo, GCON (Deceased) 1976-1977 7. Chief Toye Coker, SAN (Deceased) 1977-1978 8. Chief Dr. G. C. M. Onyuike, SAN (Deceased) 1978-1979 9. Chief T.O. S. Benson, CFR, SAN (Deceased) 1979-1980 10. Hon. Justice Fatayi-Williams, GCON (Deceased) 1980-1981 11. Chief R.O.A. Akinjide, CON, SAN (Deceased) 1981-1982 12. Hon. Justice A.G. Irikefe, GCON (Deceased) 1982-1983 13. Alh. A. G. F. Abdul-Razaq, OFR, SAN (Deceased) 1983-1984 14. Hon. Justice Kayode Eso, CON (Deceased) 1984-1985 15. Chief F.R.A. Williams, CFR, SAN (Deceased) 1985-1986 16. Hon. Justice Mamman Nasir, GCON (Deceased) 1986-1987 17. Hon. Justice A.O. Obaseki, CON (Deceased) 1987-1988 18. Webber George Egbe, QC, SAN (Deceased) 1988-1989 19. Hon. Judge Prince Bola CFR, SAN 1989-1990 20. Chief Bankole Oki, SAN (Deceased) 1992-1993 1 TheNigerialawyer(c) Copyright 21. Hon. Justice M.L. Uwais, GCON 1993-1994 22. Mr. Kehinde Sofola, CON, SAN (Deceased) 1994-1995 23. Hon. Justice M.M.A Akanbi, CON (Deceased) 1995-1996 24. -

International Lawyers As Disrupters of Corruption: Business and Human Rights in Africa’S Most Populous Country—Nigeria

Northwestern Journal of Human Rights Volume 18 Issue 2 Spring Article 1 Spring 2020 International Lawyers as Disrupters of Corruption: Business and Human Rights in Africa’s Most Populous Country—Nigeria Jayanth K. Krishnan Indiana University-Bloomington Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jayanth K. Krishnan, International Lawyers as Disrupters of Corruption: Business and Human Rights in Africa’s Most Populous Country—Nigeria, 18 NW. J. HUM. RTS. 93 (2020). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol18/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2020 by Jayanth K. Krishnan Volume 18, Number 2 (2020) Northwestern Journal of Human Rights INTERNATIONAL LAWYERS AS DISRUPTERS OF CORRUPTION: BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN AFRICA’S MOST POPULOUS COUNTRY—NIGERIA Jayanth K. Krishnan1* ABSTRACT—Be it bribery, embezzlement, or the abuse of public trust, corruption poses a major challenge to global security and democratic governance, along with undermining the rule of law, especially within the Global South. Key to this phenomenon is understanding how lawyers are enabling but also disrupting this epidemic. Unfortunately, the literature on this subject is lacking. This study, therefore, offers a nuanced story of globalization and the complicated role that lawyers play in corruption, by relying on the case study of Nigeria—a crucial Global South market that has the largest population on the African continent. -

Sexual Diversity and Human Rights in Nigeria

REPORT OF THE SURVEY ON SEXUAL DIVERSITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN NIGERIA BY INCRESE WITH FUNDING SUPPORT PROVIDED BY THE FORD FOUNDATION SEPTEMBER 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS..........................................................................................viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... ix ES1.1: Introduction and statement of the problem .................................................. ix ES1.2 Research questions............................................................................................ ix ES1.3 Aims and objectives ........................................................................................... x ES1.7 Significance/justification ................................................................................... x ES2 Methodology .......................................................................................................... x ES 3.2 Findings from quantitative research.............................................................. xi ES3.3 Findings from qualitative data........................................................................ xii ES4 Recommendations ..............................................................................................xiii CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................................. -

Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation Delegates to the National Conference

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF THE FEDERATION DELEGATES TO THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE ELDER STATESMEN S/N DELEGATES 1. Dr. Tunji Braithwaite 2. Chief Ayo Adebanjo 3. Chief Richard Akinjide 4. Chief Olu Falae 5. Erelu Olusola Obada 6. Chief Afe Babalola, SAN 7. General Ike Nwachukwu 8. Iyom Josephine Anenih 9. Senator Jim Nwobodo 10. Chief Mike Ahamba, SAN 11. Senator Azu Agboti 12. Chief Peter Odili 13. King Alfred Diete Spiff 14. Edwin K. Clark 15. Daisy Danjuma 16. Prof. Evara Ejemot Esu, OFR 17. Chief Nduese Esiene 18. Prof. Ambrose Okwoli 19. Alhaji Abdulahi Ohoimah 20. Prof. Ibrahim Gambari 21. Mr. Dogara Mark Ogbole 22. Prof. Jerry Gana 23. Gen. Jonathan Temlong 24. Prof. Jubril Aminu 25. Alhaji Ahmadu Adamu Muazu 26. Arc. Ibrahim Bunu 27. Amb. Yerima Abdullahi 28. Mr. John Mamman 29. Alhaji Adamu Waziri 30. Alhaji Umaru Musa Zandan 31. Prof. Mohammed Jumari 32. Mallam Tanko Yakassai 33. Senator Ibrahim Idah 34. Hon. Justice Usman Mohammed Argungu 35. Prof. Sambo Jinadu 36. Ishia Aliyu Gusau 37. General A. B. Mamman Nominees for the National Conference Page 1 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF THE FEDERATION DELEGATES TO THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE RETIRED MILITARY AND SECURITY PERSONNEL (i) RETIRED ARMY, NAVY & AIR FORCE OFFICERS (RANAO) ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA (ARPON) S/N DELEGATES 1. Gen. Zamani Lekwot 2. Maj. Gen. Alex Mshelbwala 3. Rear Adm CS Ehanmo 4. Brig. Gen. (Barr.) DO Idada-Ikponmwen 5. Group Capt Ohadomere 6. Gen. Raji Rasaki (ii) ASSOCIATION OF RETIRED POLICE OFFICERS OF NIGERIA (ARPON) S/N DELEGATES 1. -

The Sixth National Assembly and Constitutional Amendment in Nigeria- a New Era Or a Fait Accompli? Hassan I

Scholars International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Law Crime Justice ISSN 2616-7956 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3484 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://scholarsmepub.com/sijlcj/ Review Article The Sixth National Assembly and Constitutional Amendment in Nigeria- A New Era or a Fait Accompli? Hassan I. Adebowale* Senior Lecturer Department of Private Property Law, Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State DOI: 10.36348/SIJLCJ.2019.v02i10.005 | Received: 15.10.2019 | Accepted: 22.10.2019 | Published: 27.10.2019 *Corresponding author: Hassan I. Adebowale Abstract The history of constitutional development in Nigeria reveals the tortuous road the legislators have taken to bestow a legacy of a befitting Constitution. Constitutional provisions on amendment are tedious, and sometimes, manifestly insurmountable. It therefore behoves the National Assembly to painstakingly adhere to the various provisions of the Constitution in order to fill the lacunae in the Nigeria corpus juris which has constantly plagued the country‟s political, judicial and socio-economic sectors. From the colonial era, it has always been the same story of exploring different types of constitution. This “try and error” approach has never yielded any acceptable grundnorm for the Federal Government of Nigeria. The peculiar composition of Nigeria as a multilingual, multi-culture and religiously diversified country has virtually been cited as the key issue in Nigeria‟s tortuous road to a satisfactory constitutional achievement. The much touted “unity in diversity” has proved to be nothing more than political slogan. With the pervasive cry for restructuring in Nigeria, and the continuous failure of successive governments to find sustainable solutions to the yearnings and cravings of the citizenry, this writer looks back at where it all went wrong. -

Nec Bundle Dec 2020

2 3 4 5 6 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS NBA PRAYER 2 PRESIDENT 3 GENERAL SECRETARY 4 NATIONAL OFFICERS 5 NEC NOTICE 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 MINUTES OF PRE-CONFERENCE NEC MEETING 9 MINUTES OF EMERGENCY NEC MEETING 35 COMMUNIQUE 60 PRESIDENT’S SPEECH NBA FINANCIAL STATEMENT 61 NBA COMMITTEE REPORTS I. SECTION ON PUBLIC INTEREST AND 85 DEVELOPMENT LAW REPORT II. SECTION ON BUSSINES LAW REPORT 101 III. SECTION ON LEGAL PRACTICE REPORT 110 IV. WOMEN’S FORUM 113 V. YOUNG LAWYERS’ FORUM 126 VI. REPORT OF NBA GENERAL PURPOSE COMMITTEE 131 VII. NBA CAC TASK FORCE COMMUNIQUE 132 8 MINUTES OF THE PRE-AGC NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (NEC) MEETING OF THE NIGERIAN BAR ASSOCIATION, HELD ON 20TH AUGUST, 2020 AT THE AUDITORIUM, NBA NATIONAL SECRETARIAT, ABUJA. 1.0. IN ATTENDANCE: A. NATIONAL OFFICERS 1) PAUL USORO, SAN PRESIDENT 2) JONATHAN GUNU TAIDI, ESQ GENERAL SECRETARY 3) STANLEY CHIDOZIE IMO, ESQ 1ST VICE PRESIDENT 4) DR. FOLUKE DADA, ESQ 2ND VICE PRESIDENT 5) THEOPHILUS TERHILE IGBA, ESQ 3RD VICE PRESIDENT 6) BANKE OLAGBEGI-OLOBA, ESQ TREASURER 7) NNAMDI INNOCENT EZE, ESQ LEGAL ADVISER 8) JOSHUA ENEMALI USMAN, ESQ WELFARE SECRETARY 9) ELIAS EMEKA ANOSIKE, ESQ FINANCIAL SECRETARY 10) OLUKUNLE EDUN, ESQ PUBLICITY SECRETARY 11) EWENODE WILLIAM ONORIODE, ESQ 1ST ASST. SECRETARY 12) CHINYERE OBASI, ESQ 2ND ASST. SECRETARY 13) IRENE INIOBONG PEPPLE, ESQ ASST. FIN. SECRETARY 14) AKOREDE HABEEB LAWAL, ESQ ASST. PUB. SECRETARY B. PAST PRESIDENTS 1) O. C. J. OKOCHA, MFR, SAN, JP, DSSRS 2) DR OLISA AGBAKOBA, SAN 3) AUGUSTINE ALEGEH, SAN C. PAST GENERAL SECRETARIES 1) HAIRAT BALOGUN 2) HON. -

Tribunale Di Milano Vii Sezione Penale

VERBATIM - SOCIETA' COOPERATIVA A RESPONSABILITA' LIMITATA SOCIA DEL CONSORZIO CICLAT TRIBUNALE DI MILANO VII SEZIONE PENALE ***** RITO COLLEGIALE AULA BUNKER 1 - MI0035 DOTT. MARCO TREMOLADA Presidente DOTT. MAURO GALLINA Giudice a Latere DOTT. ALBERTO CARBONI Giudice a Latere DOTT. FABIO DE PASQUALE Pubblico Ministero DOTT. SERGIO SPADARO Pubblico Ministero DOTT. GIOVANNI DECARO Cancelliere SIG. PIERPAOLO NUTRICATI Ausiliario tecnico VERBALE DI UDIENZA REDATTO CON IL SISTEMA DELLA FONOREGISTRAZIONE E SUCCESSIVA TRASCRIZIONE VERBALE COSTITUITO DA NUMERO PAGINE: 78 PROCEDIMENTO PENALE NUMERO 54772/13 R.G.N.R. PROCEDIMENTO PENALE NUMERO 1351/18 R.G. A CARICO DI: SCARONI PAOLO + 14 UDIENZA DEL 02/07/2020 TICKET DI PROCEDIMENTO: P2020204221911 Esito: RINVIO AL 21/07/2020 R.G. 1351/18 - TRIBUNALE DI MILANO VII SEZIONE PENALE - 02/07/2020 - C/SCARONI PAOLO + 14 - 1 di 78 VERBATIM - SOCIETA' COOPERATIVA A RESPONSABILITA' LIMITATA SOCIA DEL CONSORZIO CICLAT INDICE ANALITICO PROGRESSIVO CONCLUSIONI DELLE PARTI....................................................................................................3 Requisitoria del Pubblico Ministero.........................................................................................3 Requisitoria del Pubblico Ministero.......................................................................................23 Requisitoria del Pubblico Ministero.......................................................................................42 Requisitoria del Pubblico Ministero.......................................................................................57 -

Senior Advocates of Nigeria (San)

SENIOR ADVOCATES OF NIGERIA (SAN) S/N NAMES DATE CHIEF F.R.A. WILLIAMS, S.A.N. 1 4/3/1975 (DECEASED) DR. N.B. GRAHAM-DOUGLAS, S.A.N. 2 4/3/1975 (DECEASED) CHIEF OBAFEMI AWOLOWO, S.A.N. 3 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) CHIEF R.A. FANI-KAYODE, S.A.N. 4 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) 5 T.A. BANKOLE OKI, S.A.N. (DECEASED) 1/12/1978 6 E.A. MOLAJO, S.A.N. (DECEASED) 1/12/1978 7 KEHINDE SOFOLA, S.A.N. (DECEASED) 1/12/1978 8 CHIEF R.O.A. AKINJIDE, S.A.N. 1/12/1978 9 CHIEF G.O.K. AJAYI, S.A.N. 1/12/1978 CHIEF OLISA CHUKWURA, S.A.N. 10 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) DR. NWAKANMA OKORO, S.A.N. 11 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) DR. MUDIAGA ODJE, S.A.N. 12 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) 13 P.O. BALONWU, S.A.N. 1/12/1978 14 PROFESSOR B.O. NWABUEZE, S.A.N. 1/12/1978 DR. AUGUSTINE NNAMANI, S.A.N. 15 1/12/1978 (DECEASED) 16 G.C.M. ONYIUKE, S.A.N. (DECEASED) 1/25/1979 CHIEF B. OLOWOFOYEKU, S.A.N 17 1/25/1979 (DECEASED) 18 H.A. LARDNER, S.A.N. (DECEASED) 1/25/1979 19 CHIKE OFODILE, S.A.N. 1/25/1979 20 PROFESSOR A.B. KASUMUM, S.A.N. 1/25/1979 21 F.O. AKINRELE, S.A.N. 3/6/1980 CHIEF ADEBAYO OGUNSANYA, S.A.N. 22 3/6/1980 (DECEASED) 23 OKOI ARIKPO, S.A.N.