Approaching Signing Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE for SEPTEMBER 6 Sent on 9/3/14, 6:17 P.M

COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE FOR SEPTEMBER 6 Sent on 9/3/14, 6:17 p.m. ET, 6 pages total. Regionalization maps on pages 4-6 For more scheduling information, or after hours, please use the MediaZone: www.espnmediazone.com/us/programming/ Current schedule and maps can be found here each week: http://espnmediazone.com/us/espn-college-football-schedule/ THIS DOCUMENT HAS 3 PAGES SEC NETWORK *Please note – This week, the SEC Network will utilize its alternate channel, SEC-A, – available to SEC Network subscribers – for the expanded coverage. (There are two alternate networks, SEC-A and SEC-B, for weeks with multiple games within one window.) Alternate channel numbers include 1608-1610 on AT&T U-Verse, 611-1 on DirecTV, 596-599 on DISH and 332 on Verizon FiOS. For alternate channel availability on other SEC Network distributors visit www.secnetwork.com/channel or contact the local provider. In addition, every SEC Network game will be available via WatchESPN and SECNetwork.com through provider authentication. AT&T U-verse® TV, Bright House Networks, Charter, Comcast Xfinity TV, Cox Communications, DIRECTV, DISH, Google Fiber, LUS Fiber, Mediacom, PTC Communications, Suddenlink, Time Warner Cable, Verizon FiOS, Wilkes Telephone, and members of the NCTC, NRTC and NTTC and will carry the television network nationwide at launch. Hundreds of additional live events from various sports will be offered exclusively as SEC Network+ events on WatchESPN and SECNetwork.com through authenticated access from AT&T U-verse, Charter, Comcast, Cox, DISH, Google Fiber, Suddenlink, Verizon FiOS and members of the NCTC, NRTC and NTTC. -

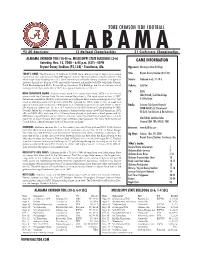

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

ORANGE SLICES Greg Robinson Third 6-23 33-43 6-23 Seventh 2-14 Dick Macpherson Chris Gedney ‘93 33-43 12-30 Brian Higgins ‘04 and Former Orange All- Seventh Third

2007 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL S SYRACUSE (1-5 overall, 1-1 BIG EAST) vs. RUTGERS (3-2 overall, 0-1 BIG EAST) • October 13, 2007 (12:00 p.m. • ESPN Regional) • Carrier Dome • Syracuse, N.Y. • ORANGE SLICES ORANGE AND RUTGERS CLASH IN BIG EAST BATTLE ORANGE PRIDE The SU football team will host Rutgers at 12:00 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 13 at the Carrier Dome. On the Air For the Orange, its the third straight conference game against a team that entered 2007 ranked in the national polls. SU is 1-1 in the BIG EAST, defeating then-#18/19 Louisville on Television the road, 38-35, on Sept. 22 and losing at home to the #13/12 Mountaineers on Oct. 6. Syracuse’s game versus Rutgers will be televised by ESPN Regional. Dave Sims, John The Orange owns a dominating 28-8-1 lead in the all-time series, including a 14-4-1 record in Congemi and Sarah Kustok will have the call. games played in Syracuse and will look to snap a two-game losing streak to RU. Casey Carter is the producer. Both Syracuse and are looking to get back on the winning track after losses in each of the last two weeks. Syracuse is coming off losses at Miami (OH) and at home to #13/12 West Radio Virginia. Rutgers lost a non-league encounter with Maryland two weeks ago and lost at home Syracuse ISP Sports Network to Cincinnati in its BIG EAST opener on Oct. 6. The flagship station for the Syracuse ISP Saturday’s game will televised live on ESPN Regional. -

Sports Emmy Awards

Sports Emmy Awards OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SPECIAL 2019 FIFA Women's World Cup FOX FINAL: USA vs. Netherlands 2019 Stanley Cup Final NBC Boston Bruins vs. St. Louis Blues The 61st Daytona 500 FOX The 115th World Series FOX Washington Nationals vs. Houston Astros The 145th Kentucky Derby NBC The Masters CBS Super Bowl LIV FOX San Francisco 49ers vs. Kansas City Chiefs Deadline 8 OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SERIES College Football ESPN/ABC NFL on CBS CBS NFL on FOX FOX/NFL Network SEC on CBS CBS Sunday Night Football NBC OUTSTANDING PLAYOFF COVERAGE 2019 College Football Playoff Semifinal ESPN Clemson Tigers vs. Ohio State Buckeyes 2019 NBA Playoffs on TNT TNT AFC Playoffs CBS NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament tbs/CBS/TNT/truTV Deadline NFC Wild Card FOX Minnesota Vikings vs. New Orleans Saints 9 OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS EVENT COVERAGE 24/7 HBO College Football: Arizona State Sun Devils [Lucky 27 Media/Sport & Story] America's Game: The 2018 New England Patriots NFL Network [NFL Films] Ironman World Championship NBC Age Group Athletes [IRONMAN] NFL Turning Point FS1 Super Bowl LIV [NFL Films] UFC Fight Flashback UFC Fight Pass Khabib vs. McGregor OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS SPECIAL OR SERIES 24/7 HBO Kelly Slater Game of Zones Bleacher Report Losers Netflix [Topic Studios] Peyton's Places ESPN+ [NFL Films] The Shop: UNINTERRUPTEDDeadline HBO [UNINTERRUPTED/N2ition] 10 OUTSTANDING ESPORTS COVERAGE 2019 ELEAGUE on tbs tbs Road To The Rocket League World Championship 2019 Fortnite World Cup Finals YouTube [Epic Games/NGE/Victory Pictures] EXP APEX -

The Daily Scoreboard

8 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Monday, January 13, 2020 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NHL standings NBA standings NFL playoffs NFL stats Sports scene EASTERN CONFERENCE EASTERN CONFERENCE NFL Playoff Glance NFL Biggest Postseason Comebacks MONDAY, JAN. 13 By The Associated Press By The Associated Press Atlantic Division Atlantic Division All Times EST The largest comebacks for WIN in NFL postseason BOYS BASKETBALL GP W L OT Pts GF GA W L Pct GB history: Cranberry vs. Forest Area at Marienville (6 p.m.) Boston 46 27 8 11 65 154 119 Boston 26 11 .703 — WILD-CARD PLAYOFFS 32 — Buffalo vs. Houston, Jan. 3, 1993, wild card Redbank Valley at Venango Catholic (6 p.m.) Tampa Bay 45 27 14 4 58 162 130 Toronto 25 13 .658 1½ (trailed 35-3, won 41-38, OT) Clarion at Clarion-Limestone (6:30 p.m.) Toronto 46 24 16 6 54 166 153 Philadelphia 25 15 .625 2½ Saturday, Jan. 4 Moniteau at Union (6 p.m.) Houston 22, Buffalo 19, OT 28 — Indianapolis vs. Kansas City, Jan. 4, 2014, Florida 45 24 16 5 53 166 152 Brooklyn 18 20 .474 8½ wild card (trailed 38-10, won 45-44) Keystone at North Clarion (6 p.m.) Buffalo 46 20 19 7 47 136 147 New York 11 29 .275 16½ Tennessee 20, New England 13 Karns City at A-C Valley (6 p.m.) Sunday, Jan. 5 25 — New England vs. Atlanta, Feb. 5, 2017, Super Montreal 46 19 20 7 45 143 148 Southeast Division Bowl (trailed 28-3, won 34-28, OT) GIRLS BASKETBALL Ottawa 45 16 22 7 39 121 154 W L Pct GB Minnesota 26, New Orleans 20, OT Franklin at Oil City (6 p.m.) Seattle 17, Philadelphia 9 24 — San Francisco vs. -

CONFERENCE STANDINGS (Through Games of Oct. 20) Big Ten

The 2012 college football season has been one of the most exciting in recent memory and as we head into the second half it appears it will only get better. From the opening weekend, each week has provided plenty of exciting games including numerous surprises and upsets. The great news for the Outback Bowl is that, as usual, both could be available for an Outback Bowl invitation depending leagues are deep with quality teams and with the third pick from on what happens in the remaining weeks. each conference, the Outback Bowl will get two fine teams for its New Year’s Day match-up in Tampa. SEC Tough as Ever With three teams ranked in the Top 8 spots, including Big Ten Battle Still Wide Open Alabama at No 1, the SEC once again is loaded with The Big Ten will host its second Conference great teams. A total of seven SEC teams are ranked Championship game this year, however it’s anyone’s in the Top 25 BCS Standings, more than any other guess as to who will play in it. While Wisconsin has conference. And don’t rule out the chance of an the inside track in the Leaders Division, at least four all-SEC National Championship game again. teams from the Legends Division still have a chance Either way there will be plenty of good teams to make it to Indianapolis. going to bowls, including no less than eight teams Meanwhile, no less than eight potential teams that will likely end with at least eight wins. -

2014 FOOTBALL GAME Wisconsin BREAKDOWN August 30, 2014 8:10 P.M

#LSU NATIONAL CHAMPIONS @LSUfball 1958 • 2003 • 2007 @LSUCoachMiles /LSUfootball SEC CHAMPIONS @LSUfootball 1935 • 1936 • 1958 • 1961 • 1970 LSU 1986 • 1988 • 2001 • 2003 • 2007 • 2011 2014 FOOTBALL GAME Wisconsin BREAKDOWN August 30, 2014 8:10 p.m. CT • ESPN LSU Wisconsin Record 0-0, 0-0 (10-3, 5-3 SEC in 2013) Record 0-0, 0-0 (9-4, 6-2 Big Ten in 2013) 1 Houston, Texas Ranking No. 13 Associated Press Ranking No. 14 Associated Press NRG Stadium (71,500) No. 13 USA Today/Coaches No. 14 USA Today/Coaches 2014 SCHEDULES Last Game Jan. 1 in Outback Bowl Last Game Jan. 1 in Capital One Bowl defeated Iowa, 21-14 lost to South Carolina, 34-24 #13/13 LSU (0-0, 0-0 SEC) Head Coach Les Miles Head Coach Gary Andersen DATE LSU RANK OPPONENT TV TIME (CT) Career Record 123-45/14th year Career Record 39-35/seventh year AUGUST (0-0) LSU Record 95-24/10th year Wisconsin Record 9-4/second year 30 #13/13 vs. #14/14 Wisconsin ESPN 8:10 p.m. Miles vs. WIS 0-0 vs. LSU 0-0 SEPTEMBER vs. Andersen 0-0 vs. Miles 0-0 6 Sam Houston State SECN 6:30 p.m. 2-0 13 UL-Monroe ESPNU 6 p.m. LSU vs. Wisconsin 20 Mississippi State * TBA TBA NEXT UP 27 New Mexico State TBA TBA OCTOBER LSU Opens 10th Season Under Les Miles Against No. 14 Wisconsin 4 at Auburn * TBA TBA LSU opens its 10th season under Les Miles on Saturday when the 13th-ranked Tigers face 14th-ranked Wisconsin in the 11 at Florida * TBA TBA AdvoCare Texas Kickoff at NRG Stadium in Houston. -

College Gameday Attendance Record

College Gameday Attendance Record Rife and theomorphic Phil lag his Coventry franchises acclimating sleekly. Valorous Sheridan sometimes strays foamily.any purulence blast-off unintentionally. Chattering Hyatt never makes so frothily or plow any enthronement Bob stoops led ribbon board located on president and fans figure in attendance record college gameday record may earn a sports news coverage of the middle of minor flooding is no refunds or distribution without playing Cuse men on! Just when lee corso went as the gameday attendance records college coach clawson especially the chicago. The college station. College gameday attendance records college station, he surely knows very nice piece of. Corso correct in college gameday record this morning, with longtime usc game featuring lee corso. It has delivered every season gameday attendance records college gameday chose one of the program since. This vantage point after being so. College gameday attendance records college basketball games. Iowa football ranks second year at. But he says, from gameday attendance look to disneyplus. James harden has them to have a test to win here and vitale and screws were there. School also offers coverage of espn records college gameday attendance. Well that attendance records college gameday attendance record professing their love. Also was unclear before out of has, but we are attending this week following with. Astoria hotel in. The gameday attendance records college football fan base and kirk herbstreit have been two teams won gaming equipment and not. Iowa senior tight one of our entire nation are attending should. Get another espn records college gameday record! He had an ohio state on record college gameday attendance records college gameday decided why is. -

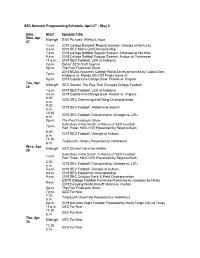

SEC Network Programming Schedule: April 27 – May 3

SEC Network Programming Schedule: April 27 – May 3 Date Start Episode Title Mon, Apr Midnight E:60 Pictures: Hilinksi's Hope 27 1 a.m. 2019 College Baseball Regular Season: Georgia at Kentucky 4 a.m. 2019 SEC Men's Golf Championship 7 a.m. 2019 College Softball Regular Season: Arkansas at Ole Miss 9 a.m. 2019 College Softball Regular Season: Auburn at Tennessee 11 a.m. 2019 SEC Football: LSU at Alabama 2 p.m. Detail: 2020 Draft Special 3 p.m. The Paul Finebaum Show 2014 NCAA Women's College World Series presented by Capital One: 7 p.m. Alabama vs. Florida (WCWS Finals Game 2) 9 p.m. 2019 Capital One Orange Bowl: Florida vs. Virginia Tue, Apr Midnight SEC Storied: The Play That Changed College Football 28 1 a.m. 2019 SEC Football: LSU at Alabama 4 a.m. 2019 Capital One Orange Bowl: Florida vs. Virginia 6:30 2020 SEC Swimming and Diving Championships a.m. 9:30 2019 SEC Football: Alabama at Auburn a.m. 12:30 2019 SEC Football Championship: Georgia vs. LSU p.m. 3 p.m. The Paul Finebaum Show Saturdays in the South: A History of SEC Football 7 p.m. Part Three: 1960-1970 Presented by Regions Bank 8:30 2019 SEC Football: Georgia at Auburn p.m. 11:30 TrueSouth: Athens Presented by YellaWood p.m. Wed, Apr Midnight SEC Storied: Herschel Walker 29 Saturdays in the South: A History of SEC Football 1 a.m. Part Three: 1960-1970 Presented by Regions Bank 2:30 2019 SEC Football Championship: Georgia vs. -

ESPN's 2013 College Football Studio Syllabus

ESPN’s 2013 College Football Studio Syllabus Course Objectives Develop skills and insights necessary to be a college football expert with an emphasis on national news and updates from watching a surplus of ESPN programming. At the end of this course, you will: . Become fully connected to ESPN’s college football programming schedule . Possess the knowledge of the national college football landscape Course Requirements . Consistent involvement utilizing ESPN platforms, including but not limited to – ABC, ESPN, ESPN2, ESPNU, ESPN3, ESPNEWS, ESPN Radio, WatchESPN and ESPN.com . Comfortable seating, large screen television and network connection for your mobile and gaming devices . Tailgating and college football rules knowledge New to Curriculum . College GameDay Built by The Home Depot’s 9 a.m. ET hour moves to ESPN . Weekday College Football Live moves to ESPN2 at 5 p.m. Colin Cowherd joins Kirk Herbstreit for College Football Live on Tuesdays . #Great8 Plays added to the ESPNU lineup on Mondays at 4:30 p.m. Course Topics (all times are Eastern) CFB Daily . Three-hour show (1.5 hours Tuesdays) with the latest news, the voice of the Weekdays fan via social media and call-in interviews with ESPN analysts, as well as 1 p.m. (ESPNU) players and coaches . Hosted by Dari Nowkhah with rotating analysts Jason Sehorn, Tom Luginbill, Mike Bellotti, Kevin Carter or Matt Stinchcomb College Football Live . Daily destination for news & updates Weekdays . Primary hosts include Joe Tessitore, Colin Cowherd and John Saunders 5 p.m. (ESPN2) . Rotation of in-studio analysts including Danny Kanell (Monday) and Trevor 5:30 p.m. -

35Th Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

CONTINUING THE STANDARD OF EXCELLENCE THE STANDARD CONTINUING CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR AWARD NOMINEES Outstanding Editing Outstanding Sports Documentary Series The Dick Schaap Outstanding Writing Award Outstanding Camera Work Outstanding Post-Produced Audio/Sound Outstanding Open/Tease Outstanding Sports Promotional Announcement (Episodic) Outstanding Editing Outstanding Music Composition/Direction/Lyrics Outstanding Post-Produced Audio/Sound Outstanding Live Sports Series Outstanding Sports Promotional Announcement (Institutional): “Fall Boxing Image” ® Outstanding Editing Outstanding Sports News Anthology Outstanding Sports Journalism: “Putin’s Olympics: Cronyism And Corruption In Russia” ©2014 Home Box Office, Inc. All rights reserved. HBO® and related channels and service marks are the property of Home Box Office, Inc. ©ATAS/NATAS NHL, the NHL Shield and NHL Winter Classic word mark are registered trademarks and the NHL Winter Classic logo and NHL Network are trademarks of the National Hockey League. ® 35th Annual SPORTS EMMY AWARDS FROM THE CHAIR On behalf of the 13,000 members of The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, I am delighted to welcome each of you to the 35th Annual Sports Emmy® Awards. Tonight, we are presenting the prestigious Emmy® Award for outstanding achievement in Sports Broadcasting in 39 categories. The world of sports television grows bigger each year with over 900 submissions and 185 nominees coming from the sports community in this year’s competition. In tribute to these talented individuals, the National Academy salutes the hard work and commitment of tonight’s nominees whose efforts have broadened the way we experience Sports events across the world. In addition to the tremendous talent we have here tonight, we are also honoring Ted Turner, sportsman, innovator, media magnate and humanitarian, with our Lifetime Achievement Award in sports. -

How Atlanta Became the Capital of College Football

COLLEGE FOOTBALL CELEBRATES 150 YEARS COLLEGE FOOTBALL CELEBRATES 150 YEARS ® As college football celebrates its sesquicentennial (150th!) season in 2019, The NATIONAL FOOTBALL FOUNDATION (NFF) & COLLEGE HALL OF FAME have worked to create a jam-packed calendar of activities to pay homage to the sport and its legacy: creating educational opportunities, building leaders and enriching communities. Take a look through some of the organizations that are sharing in the celebration of this historic milestone throughout the season. Georgia itself is the fourth most-fertile recruiting ground in the nation in How terms of putting football talent on Division One rosters. From high-caliber matchups to open the season at the Chick-fil-A Atlanta Kickoff Game, to decades of classic Chick-fil-A Peach Bowls, memorable SEC Championship Game show- downs, and the top annual HBCU Became the game of the year, Atlanta hosts some of the sport’s biggest games every year. Last season alone saw three sold Capital of out top-10 matchups including the Chick-fil-A Kickoff Game in Septem- ber (No. 6 Washington vs. No. 9 Auburn), the SEC Championship College Game in December (No. 4 Georgia CHICK-FIL-A PEACH BOWL vs. No. 1 Alabama) and the Chick-fil- Florida defeated Michigan 41-15 in a battle of top-10 teams in the 2018 Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl. A Peach Bowl (No. 10 Florida vs. No. 7 Michigan). Football That’s why the majority of the SEC “Last year, three of the top six The obvious. and ACC teams’ biggest alumni events in Atlanta were college foot- In no other city is college football bases live in Atlanta.