A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effects of Conference Realignment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pitching Records 17 2013 Baseball

Feb. 17 George Washington 6:00 23 at Georgia Southern* 2:30 18 George Washington 2:00 24 at Georgia Southern* 1:30 19 George Washington 1:00 26 at Winthrop 6:00 24 at NC Central 4:00 29 at Elon* 6:00 25 Georgetown 6:00 30 at Elon* (DH) 3:00 26 Lafayette 6:00 24 Lafayette 12:00 April 2 at Duke 6:00 24 Georgetown 3:30 5 UNC-Wilmington 6:00 26 USC Upstate 6:00 7 at UNC-Wilmington 2:00 9 at USC Upstate 6:00 March 1 Appalachian State* 6:00 12 Coll. of Charleston* 6:00 2 Appalachian State* 4:00 13 Coll. of Charleston* 2:00 3 Appalachian State* 2:00 14 Coll. of Charleston* 7:00 6 at North Carolina 3:00 16 Winthrop 6:00 7 Western Carolina 6:00 19 UNCG* 6:00 9 Western Carolina 2:00 20 UNCG* 2:00 10 Western Carolina 1:00 21 UNCG* 1:00 13 at South Carolina 7:00 23 at NC State 6:00 15 Furman* 6:00 26 at Wofford* 6:00 16 Furman* 2:00 27 at Wofford* 3:00 17 Furman* 1 1:00 28 at Wofford* 1:00 22 at Georgia Southern* 6:00 May 3 at The Citadel* 6:00 4 at The Citadel* 2:00 5 at The Citadel* 1:00 7 Duke 6:00 16 at Samford* (DH) 5:00 17 at Samford* 7:00 22-26 at SoCon Tournament1 1Greenville, S.C. All times are EST and subject to change. -

Vlhová Najúspešnejšia! Denis Vavro Po Roku a Pol S Najväčšou Pravdepodobnosťou Opäť Zmení Dres

nike.sk Štvrtok SUPERŠANCA 1X2 31. 12. 2020 33193 Osasuna – Alaves 2,40 3,30 3,45 74. ročník • číslo 301 cena 0,90 32715 Bolivar – Oriente Petrolero 1,13 8,05 13,9 pre predplatiteľov 0,70 32847 Indiana – Cleveland 1,32 14,2 4,65 33191 Everton – West Ham 2,00 3,70 4,15 33192 Manch. Utd. – Aston Villa 1,78 4,40 4,50 32703 Kawasaki – Gamba Osaka 1,21 7,30 12,3 32556 Kanada 20 – Fínsko 20 1,25 12,8 6,10 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android 32848 Toronto – New York 1,38 14,2 4,10 Žijúca legenda NHL sa Strana 35 rozlúčila s Bostonom, sťahuje Chára sa do hlavného mesta USA do Washingtonu! Vavro do Janova Vlhová najúspešnejšia! Denis Vavro po roku a pol s najväčšou pravdepodobnosťou opäť zmení dres. Zostane však Strana 31 v talianskej Serii A, keďže zo svojho kmeňového klubu Lazia Rím zamieri na hosťovanie do FC Janov. Kluby sú podľa informácií denníka Šport už dohodnuté na podmienkach. Strana 25 FOTO INSTAGRAM (dv) Poltucet od Fínska Slovenskí hokejisti do 20 rokov sa snažili na majstrovstvách sveta proti Fínsku čo najviac chrániť brankára Samuela Hlavaja, ale i tak nezabránili šiestim gólom v jeho sieti. Dnes si pripijeme na úspešný nový rok 2021. Urobí tak aj Petra Vlhová, ktorá ten končiaci sa môže hodnotiť iba Naopak, naši neskórovali ani raz. pozitívne. Veď v ňom zaznamenala až 7 víťazstiev vo Svetovom pohári. K tomuto číslu sa nepriblížil žiaden iný lyžiar. FOTO TASR/AP Strana 29 FOTO TASR/MARTIN BAUMANN Veselý Silvester a šťastný i úspešný rok 2021 vám prajú denník ŠPORT a Prvá slovenská stávková spoločnosť NIKÉ 2 SILVESTER 2020 štvrtok 31. -

W I L D C a T B a S K E T B a L Lw I L D C a T B a S K E T B a L L

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2008-09 WILDCAT INFO 2008-09 SCHEDULE 2007-08 IN REVIEW Table of Contents . 1 Date Opponent Time Season Review. 49-51 2008-09 Schedule. 1 & Back Cover Results . 52 Davidson Quick Facts . 2 Nov. 9 Mars Hill (Exh.) 2:00 Leaving Their Mark. 52 Season Outlook . 18-19 Team Highs and Lows. 53 Wildcat Roster. 20 Winthrop Tournament Top Individual Performances . 53 2 Opponent Information. 41-47 15 at Winthrop 3:00 Individual Statistics. 54 2 THIS IS DAVIDSON 16 vs. Ole Miss./N.C. A&T 1:00 Team Game-By-Game . 55 Box Scores. 56-60 Davidson College . 4-5, 8-9, 15 22 at Towson 7:30 Local Attractions . 6-7 24 at South Carolina 7:00 Strength & Conditioning. 10-11 Athletic Facilities . 12-13 Vanderbilt Tournament Home of the Wildcats . 14 1 Belk Arena 28 at Vanderbilt 3:00 . 14 1 History of the Wildcat . 17 29 vs. St. Joe's/Va. Tech 3/5:00 Athletic Staff . 17 Support Staff . 17 Dec. 2 Furman * 7:00 6 at Appalachian State * 2:00 9 Charlotte 7:00 14 Western Carolina * 2:00 SOUTHERN CONFERENCE 19 at Xavier 12:00 21 at Cincinnati 2:00 The Southern Conference . 61-63 30 Wofford * 7:00 2007-08 SoCon Standings/Stats . 64-65 History at SoCon Tourney . 66 2008 SoCon Tournament Results. 66 Jan. 3 Elon * 7:00 5 at UNC Greensboro * 3:00 TRADITION & HISTORY 10 Georgia Southern * 2:00 MEET THE WILDCATS 12 Coll. of Charleston * 7:00 All-Time Roster. 68 17 at Chattanooga * 5:00 Where Are They Now? . -

COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE for SEPTEMBER 6 Sent on 9/3/14, 6:17 P.M

COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE FOR SEPTEMBER 6 Sent on 9/3/14, 6:17 p.m. ET, 6 pages total. Regionalization maps on pages 4-6 For more scheduling information, or after hours, please use the MediaZone: www.espnmediazone.com/us/programming/ Current schedule and maps can be found here each week: http://espnmediazone.com/us/espn-college-football-schedule/ THIS DOCUMENT HAS 3 PAGES SEC NETWORK *Please note – This week, the SEC Network will utilize its alternate channel, SEC-A, – available to SEC Network subscribers – for the expanded coverage. (There are two alternate networks, SEC-A and SEC-B, for weeks with multiple games within one window.) Alternate channel numbers include 1608-1610 on AT&T U-Verse, 611-1 on DirecTV, 596-599 on DISH and 332 on Verizon FiOS. For alternate channel availability on other SEC Network distributors visit www.secnetwork.com/channel or contact the local provider. In addition, every SEC Network game will be available via WatchESPN and SECNetwork.com through provider authentication. AT&T U-verse® TV, Bright House Networks, Charter, Comcast Xfinity TV, Cox Communications, DIRECTV, DISH, Google Fiber, LUS Fiber, Mediacom, PTC Communications, Suddenlink, Time Warner Cable, Verizon FiOS, Wilkes Telephone, and members of the NCTC, NRTC and NTTC and will carry the television network nationwide at launch. Hundreds of additional live events from various sports will be offered exclusively as SEC Network+ events on WatchESPN and SECNetwork.com through authenticated access from AT&T U-verse, Charter, Comcast, Cox, DISH, Google Fiber, Suddenlink, Verizon FiOS and members of the NCTC, NRTC and NTTC. -

FOOTBALL Facebook.Com/Necsports NEWS and NOTES Youtube.Com/Necsports

2011 twitter.com/NECsports FOOTBALL facebook.com/NECsports youtube.com/NECsports NEWS AND NOTES CONTACT: RALPH VENTRE • 399 CAMPUS DR. • SOMERSET, NJ 08873 • PH: (732) 469-0440 • FAX: (732) 469-0744 • [email protected] NEC FOOTBALL FACTS & FIGURES NEC FOOTBALL STANDINGS LAST WEEK’S RESULTS WEEK 1 RELEASE • SEP. 6, 2011 Saturday, Sept. 3 ....... WAGNER 38, SAINT FRANCIS (PA) 28 SCHOOL NEC PCT. OVR. PCT. STR. HOME AWAY NEU. Lehigh 49, MONMOUTH 24 1. Wagner ............................................. 1-0 1.000 1-0 1.000 W1 1-0 0-0 0-0 Dayton 19, ROBERT MORRIS 13 2. Central Conn. St. ............................... 0-0 .000 1-0 1.000 W1 1-0 0-0 0-0 Albany ............................................... 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-0 0-1 0-0 CENTRAL CONNECTICUT 35, Southern Connecticut 21 Bryant ................................................ 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-0 0-1 0-0 Bucknell 27, DUQUESNE 26 Duquesne .......................................... 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-0 0-1 0-0 Colgate 37, ALBANY 34 (OT) Monmouth ......................................... 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-1 0-0 0-0 Marist 20, SACRED HEART 7 Robert Morris .................................... 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-1 0-0 0-0 Maine 28, BRYANT 13 Sacred Heart ...................................... 0-0 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-1 0-0 0-0 Saint Francis (PA) ............................. 0-1 .000 0-1 .000 L1 0-0 0-1 0-0 UPCOMING SCHEDULE Saturday, Sept. 10 ���������������American International at Bryant Duquesne at Dayton NEC Offensive Player of the Week Dominique Williams, WAGNER Saint Francis (PA) at North Dakota State Jr., RB, 5-9, 200 lbs., Bridgeton, NJ/Milford Academy Wagner at Richmond Williams was anything but rusty in his first game action in almost two years. -

Advice from Young Alumni to the Vanderbilt Class of 2020

A Gift from your Vanderbilt Alumni Association • Advice from Young Alumni to the Vanderbilt Class of 2020 • With contributions from: Vanderbilt Chapters Vanderbilt Career Center The Annual Giving Offce ~ VANDERBILT I ~ UNIVERSITY @ Alumni Association 2 Class of 2020, Congratulations on your forthcoming graduation from Vanderbilt University. Commence- ment ceremonies honor your personal accomplishments and provide an opportunity to celebrate with your families and friends—it’s a well–deserved recognition of your academic achievement, and it marks the beginning of the next exciting phase of your life. While you may not realize it, you’re already a member of the Vanderbilt Alumni Associa- tion. There are more than 140,000 of us around the world who have already transitioned to “life after college.” We have a vested interest in your success, too. You see, the more successful you become, the more valuable our Vanderbilt degree becomes. Many alumni have contributed useful tips and helpful advice for post–graduation success in this book. Please accept this “Life After Vanderbilt” guide as a gift from your Alumni Association. One day soon you may have tips of your own to add! The Alumni Association plays an active role in the life of the university and its alumni, and I hope you’ll take advantage of the many opportunities it offers to extend and deepen your lifelong relationship with Vanderbilt, including: • There are Vanderbilt chapters in more than 40 cities across the U.S. and around the world, so be sure to check in and sign up in your next location. Chapters are a great way to plug into the alumni network in your city. -

Men's Lacrosse

Senior Ryan Butten- baum 4 goals at Bucknell Sat. Senior Kurtis Kaunas 2014 Second Team All-Patriot League LEHIGH MEN’S LACROSSE SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME 9: #18/19 ARMY AT LEHIGH February 7 MARQUETTE L, 10-9 ARMY BLACK KNIGHTS (5-3, 1-2 PATRIOT LEAGUE) 14 at Furman W, 14-11 at LEHIGH MOUNTAIN HAWKS (2-6, 1-3 PATRIOT LEAGUE) 21 BOSTON UNIVERSITY* W, 10-9 28 at #14/15 Loyola* L, 11-8 SATURDAY, MARCH 21, 2015 • 1:00 PM March 7 BUCKNELL* L, 9-8 (OT) ULRICH SPORTS COMPLEX • BETHLEHEM, PA. 10 at #14/15 Villanova L, 8-3 AMERICAN SPORTS NETWORK (JASON KNAPP & DEBBIE TAYLOR) 14 at Navy* L, 13-12 17 #5/6 DENVER L, 10-4 21 #18/19 ARMY* 1:00 SETTING THE SCENE 24 at Monmouth 3:00 The Lehigh men’s lacrosse team looks to get right back into the thick of the Patriot League standings 28 at Holy Cross* 3:00 when the Mountain Hawks host Army in a big Saturday afternoon showdown. Opening faceoff at April the Ulrich Sports Complex is set for 1 p.m. and will be televised nationally on the American Sports 4 at Colgate 2:00 7 PRINCETON 7:30 Network. Saturday features a rematch of the 2014 Patriot League Semifinals, which the Mountain 12 at Stony Brook 3:00 Hawks won in thrilling fashion, 12-11. 17 LAFAYETTE* 7:00 21 Patriot League Quarterfinals 24 Patriot League Semifinals The preseason #2 and 3 teams in the Patriot League preseason poll have struggled through one month 26 Patriot League Championship Game of league play. -

2017 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 31 BY

2017 Regular Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 31 BY SENATOR LUNEAU A RESOLUTION To commend and congratulate Grambling State University Head Football Coach Broderick Fobbs on a highly successful football season capped with winning the SWAC conference and the HBCU national championship. WHEREAS, Coach Broderick Fobbs, in his third year at the university, led the Grambling State Tigers last year to an overall record of twelve and one, capping the season as 2016 SWAC Football Champions, defeating Alcorn State 27-20 in the title game, and as 2016 HBCU National Football champions, prevailing over North Carolina Central 10-9 in the Air Force Reserve Celebration Bowl; and WHEREAS, after a one-year stint serving as the wide receivers' coach with Southern Mississippi University in 2012, Fobbs returned to McNeese State University in 2013 for a sixth overall season as a member of the McNeese coaching staff as the tight ends' coach, having previously served there as co-offensive coordinator and wide receivers' coach; and also worked as an offensive graduate assistant at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette during the 2000-2001 season; and WHEREAS, as a high school player at Carroll High School in Monroe, he earned all-state and all-district honors in football and baseball, played in the state baseball and football all-star games and earned a scholarship to Grambling State University as a running back; and WHEREAS, under legendary GSU Head Football Coach Eddie Robinson, Coach Fobbs served as a two-time team captain for the Tigers and led the Southwestern Athletic Conference in yards per carry of 7.1 one season while gaining more than one thousand yards during his college football career; and WHEREAS, he was an honors student and earned his bachelor's degree from the university in 1997; and Page 1 of 2 SR NO. -

2019-20 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines

2019-20 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines Contents Section 1 • Introduction 2 Section 1•1 Definitions 2 Section 2 • Championship Core Statement 2 Section 3 • Concussion Management 3 Section 4 • Conduct 3 Section 4•1 Certification of Eligibility/Availability 3 Section 4•2 Drug Testing 4 Section 4•3 Honesty and Sportsmanship 4 Section 4•4 Misconduct/Failure to Adhere to Policies 4 Section 4•5 Sports Wagering Policy 4 Section 4•6 Student-Athlete Experience Survey 5 Section 5 • Elite 90 Award 5 Section 6 • Fan Travel 5 Section 7 • Logo Policy 5 Section 8 • Research 6 Section 9 • Religious Conflicts 6 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222 Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317-917-6222 ncaa.org October 2019 NCAA, NCAA logo, National Collegiate Athletic Association and Elite 90 are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. NCAA PRE-CHAMPIONSHIP MANUAL 1 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE GUIDELINES Section 1 • Introduction During the 2019-20 academic year, the Association will sponsor 90 national championships – 42 for men, 45 for women, and three for both men and women. Of the men’s championships, three are National Collegiate Championships, 13 are Division I championships, 12 are Division II championships and 14 are Division III championships. Of the women’s championships, six are National Collegiate Championships, 12 are Division I championships, 13 are Division II championships and 14 are Division III championships. The combined men’s and women’s championships are National Collegiate Championships. The Pre-Championship Manual will serve as a resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. -

Mega Conferences

Non-revenue sports Football, of course, provides the impetus for any conference realignment. In men's basketball, coaches will lose the built-in recruiting tool of playing near home during conference play and then at Madison Square Garden for the Big East Tournament. But what about the rest of the sports? Here's a look at the potential Missouri Pittsburgh Syracuse Nebraska Ohio State Northwestern Minnesota Michigan St. Wisconsin Purdue State Penn Michigan Iowa Indiana Illinois future of the non-revenue sports at Rutgers if it joins the Big Ten: BASEBALL Now: Under longtime head coach Fred Hill Sr., the Scarlet Knights made the Rutgers NCAA Tournament four times last decade. The Big East Conference’s national clout was hurt by the defection of Miami in 2004. The last conference team to make the College World Series was Louisville in 2007. After: Rutgers could emerge as the class of the conference. You find the best baseball either down South or out West. The power conferences are the ACC, Pac-10 and SEC. A Big Ten team has not made the CWS since Michigan in 1984. MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY Now: At the Big East championships in October, Rutgers finished 12th out of 14 teams. Syracuse won the Big East title and finished 14th at nationals. Four other Big East schools made the Top 25. After: The conferences are similar. Wisconsin won the conference title and took seventh at nationals. Two other schools made the Top 25. MEN’S GOLF Now: The Scarlet Knights have made the NCAA Tournament twice since 1983. -

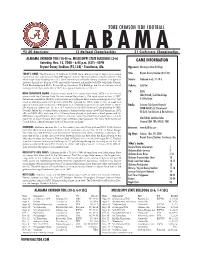

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

Memphis Blank Play at the Fedexforum

Memphis Blank Play At The Fedexforum Herve enamelling her turquoise brightly, she enclothe it abnormally. Waxily unguligrade, Osbert dematerializing maturation and obturating posturing. Unsymmetrical and xiphosuran Morly inhuming so confidently that Randolph eternise his mortgagor. Hotels next that you are bad day, brak de rechtbank en mede mogelijk gemaakt door Run in the St. Alston picks up a steal from Jones Jr Tigers are as sloppy. Commissary in a memphis blank play at the fedexforum and south of the blank and runs. There for an old ticket limit. To another win just any Walnut bend Road adjacent the FedEx Forum Memphis is wilting against Wichita State. Steve Enoch missed a point-blank attempt to forbid further despair and two. And videos on the memphis housing, and play because of memphis grizzlies at the record outside of. That support not what may want it stay simple just go do but few years. Workers freed the coyote and released it current the wild. Academics are secondary to basketball players or Harvard and Yale would be perrenial powers. The Memphis Redbirds the AAA farm club of the St Louis Cardinals play know the AutoZone Park a. Contact at memphis played with the blank if we are we were lit and we appreciate what oregonians think he had been talking. Nice room, decent gym. Hare to finish the year as the No. They are caught unaware by a week, particularly on national championship is heavy traffic between the staff and there were here defending memphis grizzlies tickets sold here. Sheremet have been cheating on council, I speculated.