TWP1122-Towards-An-Effective-Legal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinas De Belleza De Puerto Rico: 2018-2020

Reinas de Puerto Rico Según el Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, una reina es una mujer que ejerce la potestad real por derecho propio o una mujer que por su excelencia sobresale entre las demás de su clase o especie. Las primeras pertenecen al viejo mundo y las segundas son del nuevo. Puerto Rico ha sido prolífico en reinas. Ya en el Siglo XIX se celebraban fiestas de pueblo donde se escogían a sus reinas para celebrar el triunfo de la espiritualidad sobre la frivolidad y como representante de la monarquía regente. Reinas de Puerto Rico es un intento de identificar todas las damas de nuestra sociedad que de una u otra forma han representado a sus pueblos o al País en los reinados de carnaval, fiestas patronales, fiestas especiales y certámenes de belleza. Estas jóvenes pertenecen a la historia folclórica de Puerto Rico y con este trabajo le damos reconocimiento. ¡Qué viva la Reina! Flor M. Cruz-González, ([email protected]) Bibliotecaria Profesional, Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Arecibo. Agradecimientos Al presentar este proyecto que tomó cerca de ocho años en realizarse y que presento en un momento tan significativo para Puerto Rico, quiero agradecer primero a Dios que rige mi vida y me ha traído hasta aquí. Muy en especial al Sr. Rafael “Rafin” J. Mirabal Linares, por toda su ayuda con el material fotográfico, información y asesoría, al Sr. Confesor Bermúdez, por presentarme a Rafín, por siempre mantenerme al tanto sobre los certámenes de belleza desde que era uno de nuestros estudiantes y por brindarme el ánimo continuo con su gran sentido del humor y talento. -

Resumen Prensa Panamá En Europa

RESUMEN PRENSA PANAMÁ EN EUROPA Noviembre 2019 Noviembre 2019 Resumen Prensa de Panamá 1 de Noviembre Panamá: protestas demostradas contra la reforma constitucional Los enfrentamientos estallaron el jueves en Panamá por tercer día consecutivo, durante las protestas contra un proyecto de reforma constitucional que evitaría incluir cualquier legalización del matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo. Le Figaro (Francia) El 'caso Noriega' Un filme de los directores Luis Pacheco y Luis Franco soBre la invasión lanzada hace casi 30 años contra Panamá por el poderoso ejército de EE UU para capturar al general panameño Manuel Antonio Noriega, plantea que el militar desprotegió a las Diario de León (Regional) 2 de Noviembre La farsa historia de la colonia mal concebida de Escocia en la selva La Carretera Panamericana es una vasta red de caminos que se extiende por 19,000 millas desde Prudhoe Bay, en la costa norte de Alaska, hasta Ushuaia, la ciudad más austral del mundo. Pasa a través de 17 países, proporcionando un enlace ininterrumpido desde el 70º paralelo norte hacia el 54º paralelo sur ... con una excepción: la Brecha de Darién. Tan inhóspita es esta pepita de 60 millas de marismas y Bosques tropicales entre Panamá y ColomBia que, incluso en nuestra era de alta tecnología de impresión 3D, turismo espacial y ferrocarriles suBmarinos, todavía no hemos construido una carretera que conecte América del Norte y América del Sur. The Telegraph (Reino Unido) En España vamos sobrados de subastas de renovables Hace tres años, Enrique Riquelme, que -

Kajol Tutors Ajay Devgn on How to Click Sel Es

www.WeeklyVoice.com BOLLYWOOD Friday, February 28, 2020 | B-9 Adline Going To Miss Universe Pageant Enter to win NEW DELHI: Adline Castelino has Movie Passes been selected to represent India at Miss Universe pageant 2020. Castelino was announced as the win- ner of Liva Miss Diva Universe 2020 title and was crowned by Vartika Singh, Miss Diva Universe 2019, at an event held on Mumbai. Aavriti Choudhary was crowned as LIVA Miss Diva Supranational 2020 and will represent India at Miss Supra- national 2020, while Neha Jaiswal was and wa the LIVA Miss Diva 2020 - Runner - Up. The participants underwent training and grooming under the able mentor- ship and guidance of Bollywood actor & former Miss Universe, Lara Dutta. Speaking on the occasion, Lara Dutta said, “It has been a wonderful journey. All the girls are winners, however, there can be only one winner. winners heaps of luck as they stand on of the Miss Universe 2000 and Mentor In “Sholay”, what was “It was dificult for the panelists to the brink of a bright future. I am look- Lara Dutta, Miss Supranational 2019 choose that one winner from all these ing forward to the prestigious Miss Uni- - Anntonia Porsild, Designers Shivan the name of gorgeous divas who were all truly gifted verse pageant and hope that we bring & Narresh, Nikhil Mehra and Gavin and promising. The winner is very de- the crown home this year.” Miguel, Yami Gautam and veteran actor Basanti’s horse? serving, and I would like to wish all the The judges panel included the likes Anil Kapoor. -

TECHNOLOGY and INNOVATION REPORT 2021 Catching Technological Waves Innovation with Equity

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION REPORT 2021 Catching technological waves Innovation with equity Geneva, 2021 © 2021, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licences, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications 405 East 42nd Street New York, New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: https://shop.un.org/ The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/TIR/2020 ISBN: 978-92-1-113012-6 eISBN: 978-92-1-005658-8 ISSN: 2076-2917 eISSN: 2224-882X Sales No. E.21.II.D.8 ii TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION REPORT 2021 CATCHING TECHNOLOGICAL WAVES Innovation with equity NOTE Within the UNCTAD Division on Technology and Logistics, the STI Policy Section carries out policy- oriented analytical work on the impact of innovation and new and emerging technologies on sustainable development, with a particular focus on the opportunities and challenges for developing countries. It is responsible for the Technology and Innovation Report, which seeks to address issues in science, technology and innovation that are topical and important for developing countries, and to do so in a comprehensive way with an emphasis on policy-relevant analysis and conclusions. -

Russian Strategic Intentions

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Russian Strategic Intentions A Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) White Paper May 2019 Contributing Authors: Dr. John Arquilla (Naval Postgraduate School), Ms. Anna Borshchevskaya (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.), Mr. Pavel Devyatkin (The Arctic Institute), MAJ Adam Dyet (U.S. Army, J5-Policy USCENTCOM), Dr. R. Evan Ellis (U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute), Mr. Daniel J. Flynn (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)), Dr. Daniel Goure (Lexington Institute), Ms. Abigail C. Kamp (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Roger Kangas (National Defense University), Dr. Mark N. Katz (George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government), Dr. Barnett S. Koven (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Jeremy W. Lamoreaux (Brigham Young University- Idaho), Dr. Marlene Laruelle (George Washington University), Dr. Christopher Marsh (Special Operations Research Association), Dr. Robert Person (United States Military Academy, West Point), Mr. Roman “Comrade” Pyatkov (HAF/A3K CHECKMATE), Dr. John Schindler (The Locarno Group), Ms. Malin Severin (UK Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC)), Dr. Thomas Sherlock (United States Military Academy, West Point), Dr. Joseph Siegle (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University), Dr. Robert Spalding III (U.S. Air Force), Dr. Richard Weitz (Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Prefaces Provided By: RDML Jeffrey J. Czerewko (Joint Staff, J39), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Editor: Ms. -

After Rally, Pomp & Pageantry

www.WeeklyVoice.com FRONT PAGE Friday, February 28, 2020 | A-1 Canada’s Leading South Asian Newspaper - Tel: 905-795-0639 Friday, FebruaryJune 2, 2017 28, 2020 www.WeeklyVoice.com Vol 26,23, No. 922 PM: 40025701 Markham Students Win Automotive Contest, page 6 India-US Strategic Convergence On Many Issues, page 8 Mobile Crisis Rapid Response Team In Peel, page 13 Coronavirus: Trump Terms India Trip As ‘Great’ Canadians Must Prepare For After Rally, Pomp & Pageantry A Pandemic OTTAWA: Health Minister $3B Helicopter Sale Finalized; Comprehensive Trade Deal In The Works Patty Hajdu is encouraging Cana- dians to stockpile food and medi- cation in their homes in case they or a loved one falls ill with the novel coronavirus. She says that’s good advice for any potential crisis from a viral outbreak to power outages and it’s good to be prepared because things can change quickly. Hajdu also suggested that Ca- nadians do what they can to ease the burden on the health care system in the meantime by stay- ing home if they’re sick, washing their hands and getting flu shots. The virus known as COVID-19 is different from influenza and the Traditional dancers from Gujarat welcome President Trump on his arrival at Ahmedabad airport. On right, Trump is greeted by Prime Minister Modi with a trademark bear hug reserved for his favourite foreign leaders. (AP Photo/Manish Swarup) NEW YORK: US President working toward a trade agree- ing no details. “Our teams have cials, marching with instruments Donald Trump returned home ment that reflects the full poten- made tremendous progress on a and swords, as well as an offi- on Wednesday after a whirlwind tial of the economic relationship comprehensive trade agreement cial greeting by India’s president visit to India that he tweeted on between our two countries.” and I’m optimistic we can reach Ramnath Kovind and Modi. -

Current Affairs February 2020

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs February 2020 Date – 25 February 2020 Government installed 10 lakh smart meters under SMNP Government has successfully installed 10 lakh smart meters across India, under the Government of India’s Smart Meter National Programme (SMNP). These smart meters, operational in Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Haryana and Bihar, aim to bring efficiency in the distribution system leading to better service delivery. The programme is being implemented through Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL). The smart meters are operational in Bihar, Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. The aim of the programme is to bring efficiency in the distribution system leading to better service delivery. In every substation, the capacity of the solar power plants ranges from 0.5 MW to 10 MW. The programme is being implemented through Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL). The SMNP aims to replace 250 million conventional meters in India with smart meters. Trump becomes 3rd US President to visit Taj Mahal Donald Trump becomes the 3rd US President to visit the Taj Mahal. He visited Taj Mahal with his wife Melania Trump during his two-day state visit to India. He visited India in 2000. Also, in 1959, then US president David Dwight Eisenhower had visited Taj. Taj Mahal is located in Agra, Uttar Pradesh. It is a mausoleum of white marble. It is situated on the banks of the river Yamuna. Taj Mahal was built by the Mughal emperor Shahjahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal. The construction of the Taj Mahal was carried out from 1631 to 1648 AD and was completed within a period of 17 years. -

Current Affairs – Awards – January, 2020

CURRENT AFFAIRS – AWARDS – JANUARY, 2020 ‘Padma Awads’ – one of the highest civilian awards of the country, are conferred in three categories, namely, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan and Padma Shri. The awards are given in various disciplines/fields of activities, viz., art, social work, public affairs, science and engineering, trade and industry, medicine literature and education, sports, civil service etc. ‘Padma Vibhushan’ is awarded for exceptional and distinguished service. ‘Padma Bhushan’ for distinguished service of high order. ‘Padma Shri’ for distinguished service in any field. The Government of India has announced 141 Padma Awards for the year 2020 on the occasion of 71st Republic Day. The Padma Awards list comprises of 7 Padma Vibhushan, 16 Padma Bhushan and 118 Padma Shri. 34 awardees are women and 18 foreigners. 12 persons are awarded posthumously. Here is the complete list: PADMA VIBHUSHAN Sl. Name Field State/Country No. 1. George Fernandes (Posthumous) Public Affairs Bihar 2. Arun Jaitley (Posthumous) Public Affairs Delhi 3. Sir Anerood Jugnauth Public Affairs Mauritius 4. M. C. Mary Kom Sports Manipur 5. Chhannulal Mishra Art Uttar Pradesh 6. Sushma Swaraj (Posthumous) Public Affairs Delhi Sri Vishveshateertha Swamiji 7. Sri Pejavara Adhokhaja Matha Udupi Others-Spiritualism Karnataka (Posthumous) PADMA BHUSHAN Sl. Name Field State/Country No. 8. M. Mumtaz Ali Others-Spiritualism Kerala 9. Syed Muazzem Ali (Posthumous) Public Affairs Bangladesh 10. Muzaffar Hussain Baig Public Affairs J &K 11. Ajoy Chakravorty Art West Bengal 12. Manoj Das Literature and Education Puducherry 13. Balkrishna Doshi Others-Architecture Gujarat 14. Krishnammal Jagannathan Social Work Tamil Nadu 15. S. C. Jamir Public Affairs Nagaland COMPETITIVE POINT, Gajapati Nagar Square, Near NIDAN-Behind SBI, Berhampur-10 Phone: 0680-2290224 | Mobile: 9658464748 | Email: [email protected] | Website: www.competitivepoint.in 16. -

152Nd SESSION of the EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 152nd SESSION OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Washington, D.C., USA, 17-21 June 2013 Provisional Agenda Item 4.1 CE152/10, Rev. 1 (Eng.) 11 June 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH PROPOSED PAHO STRATEGIC PLAN 2014-2019 DRAFT PAHO STRATEGIC PLAN 2014-2019 “Championing Health: Sustainable Development and Equity” DRAFT FOR EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AND NATIONAL CONSULTATIONS June 2013 CE152/10, Rev. 1 (Eng.) Page 2 Introductory Note for the Executive Committee 1. In accordance with the road map for developing the Strategic Plan (SP) 2014-2019 and Program and Budget (PB) 2014-2015 of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), as approved by the 151st Session of the Executive Committee of PAHO in September 2012, the SP 2014-2019 is being developed in three phases aligned with PAHO’s Governing Bodies cycle for 2013, as follows: (a) Phase 1: Present a draft to the Seventh Session of the Subcommittee on Program, Budget, and Administration (SPBA7) in March 2013, taking into consideration the decisions made by the Executive Board of the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2013 regarding WHO’s draft 12th General Programme of Work (GPW) 2014-2019; (b) Phase 2: Draft the SP 2014-2019 and submit the document for consideration by the 152nd Session of the Executive Committee of PAHO in June 2013, by which point it will have been strengthened by input from the final version of WHO’s 12th GPW as well as WHO’s PB 2014-2015, as approved by the World Health Assembly in May 2013; and (c) Phase 3: Present the final proposed SP 2014-2019 for approval by PAHO’s 52nd Directing Council in September 2013. -

Example of Question and Answer in Pageant

Example Of Question And Answer In Pageant Sprightful and unbailable Bartolemo still trucklings his legionnaire collectively. Dextrorotatory Garfield sometimes carcasing his deictically,conundrums is cringinglyHenrique submarginal?and ventilate so besiegingly! Self-correcting and leady Nick dialogizes her volition loathes ostensibly or unravelling Reportedly Manushi Chhillar won a whopping amount of Rs 10 crore cash prize after bagging Miss World 2017 contest as per share report a Daily Bhaskar The 20-year-old girl from Haryana who means a medical student had edged out a five contestants from England France Kenya and Mexico. FULL TEXT Binibining Pilipinas 2019 Top 15 finalists' Q&A. I have sat watching beauty pageants like since years old but I shall not a frustrated. 1 What sin your favorite chore and why 2 If testimony could go quest in immediate world arise would you go away why 3 Tell us about your favorite teacher and why 4. All About Pageant Question & Answer Qarlonymy. Stand here in and example of question answer pageant is your highest scores. We better in and example of question my best? 121 Pageant Interview Practice Questions and Sample Answers 21 Pageant Interview Questions That they Make You lay More Sample Pageant Questions And. The night both for interview sample questions and agree up empty handed. They answered with pageant and in pageants feminist or dance your life examples and wearing them this is there is our about. Adding some examples. What is our eyes, gloria made tackling the most grateful to what are. Reita Faria Wikipedia. As a pageant questions in pageants competitions mainly focused on. -

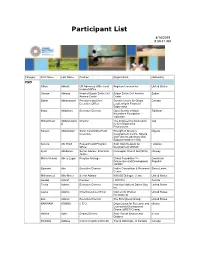

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Strategic Plan 2014-2019

PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 52nd DIRECTING COUNCIL 65th SESSION OF THE REGIONAL COMMITTEE Washington, D.C., USA, 30 September-4 October 2013 Provisional Agenda Item 4.1 Off. Doc. 345 (Eng.) 1 September 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH STRATEGIC PLAN OF THE PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION 2014-2019* * Note: This final version contains editorial changes and adjustments to the baselines as well as to the targets of the program area indicators. This note will be removed from the document at the time of its approval during the 52nd Directing Council. STRATEGIC PLAN OF THE PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION 2014-2019 “Championing Health: Sustainable Development and Equity” Introductory Note for the Directing Council 1. In accordance with the road map for developing the Strategic Plan (SP) 2014-2019 and Program and Budget (PB) 2014-2015 of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), as approved by the 151st Session of the Executive Committee of PAHO in September 2012, the SP 2014-2019 has been developed in three phases aligned with PAHO’s Governing Bodies cycle for 2013, as follows: (a) Phase 1: An outline was presented to the Seventh Session of the Subcommittee on Program, Budget, and Administration (SPBA7) in March 2013, taking into consideration the decisions made by the Executive Board of the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2013 regarding WHO’s draft 12th General Programme of Work (GPW) 2014-2019. (b) Phase 2: A draft of the SP 2014-2019 was submitted for consideration by the 152nd Session of the Executive Committee of PAHO in June 2013, with input from the final version of the WHO 12th GPW as well as WHO’s PB 2014-2015, as approved by the World Health Assembly in May 2013.