The Future Is Now: Science for Achieving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

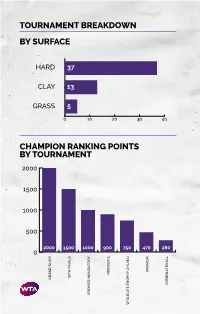

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

The Case for Stronger Regulation of Environmental Marketing

University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Summer 2020 Greenwashing No More: The Case for Stronger Regulation of Environmental Marketing Robin M. Rotman Chloe J. Gossett Hope D. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons 08. ALR 72.3_ROTMAN (ARTICLE) (DO NOT DELETE) 8/22/2020 11:30 PM GREENWASHING NO MORE: THE CASE FOR STRONGER REGULATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL MARKETING ROBIN M. ROTMAN*, CHLOE J. GOSSETT**, AND HOPE D. GOLDMAN*** Fraudulent and deceptive environmental claims in marketing (sometimes called “greenwashing”) are a persistent problem in the United States, despite nearly thirty years of efforts by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to prevent it. This Essay focuses on a recent trend in greenwashing—fraudulent “organic” claims for nonagricultural products, such as home goods and personal care products. We offer three recommendations. First, we suggest ways that the FTC can strengthen its oversight of “organic” claims for nonagricultural products and improve coordination with the USDA. Second, we argue for inclusion of guidelines for “organic” claims in the next revision of the FTC’s Guidelines for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims (often referred to as the “Green Guides”), which the FTC is scheduled to revise in 2022. Finally, we assert that the FTC should formalize the Green Guides as binding regulations, rather than their current form as nonbinding interpretive guidance, as the USDA has done for the National Organic Program (NOP) regulations. This Essay concludes that more robust regulatory oversight of “organic” claims, together with efforts by the FTC to prevent other forms of greenwashing, will ultimately bolster demand for sustainable products and incentivize manufacturers to innovate to meet this demand. -

Download File Are Today's Inequalities Limiting Tomorrow's Opportunities?

Equitable GrowthWashington Center forEquitable Growth ILLUSTRATION BY AUSTIN CLEMENS Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities? A review of the social sciences literature on economic inequality and intergenerational mobility October 2018 By Elisabeth Jacobs and Liz Hipple www.equitablegrowth.org Equitable Growth Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities? A review of the social sciences literature on economic inequality and intergenerational mobility October 2018 By Elisabeth Jacobs and Liz Hipple Contents 6 Fast facts 8 Overview 13 Definitions and metrics 14 Absolute or relative? 15 What does “high“ mobility look like? 24 Which resources should we measure? 26 Does high inequality today mean low mobility tomorrow? 32 How does economic inequality limit the development of human potential? 34 Health inequalities 38 Parental investment 44 Education 52 Conclusion to “how does economic inequality limit the development of human potential“ 54 How does economic inequality limit the deployment of human potential? 55 Changing structure of the labor market 62 Persistent discrimination 65 Household balance sheets and intergenerational mobility 68 Conclusion to “how does economic inequality limit the deployment of human potential“ 70 Conclusion 72 About the authors 73 Acknowledgements 74 Bibliography 87 Endnotes Fast facts Intergenerational mobility is the technical concept at the heart of the American Dream. An individual’s place on the economic distribution is supposed to reflect individual effort and talent, not parental resources and privilege. Yet this perspec- tive ignores the mounting evidence of the myriad ways that poverty and economic inequality foreclose equality of opportunity for far too many Americans now and in the future. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 January 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Chatzidakis, A. and Larsen, G. and Bishop, S. (2014) 'Farewell to consumerism : countervailing logics of growth in consumption.', Ephemera : theory and politics in organization., 14 (4). pp. 753-764. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/farewell-consumerism-countervailing-logics-growth- consumption Publisher's copyright statement: Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk the author(s) 2014 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org volume 14(4): 753-764 Farewell to consumerism: Countervailing logics of growth in consumption Andreas Chatzidakis, Gretchen Larsen and Simon Bishop Introduction The logic of growth is dominant in the contemporary political economy and in various notions of social and cultural prosperity (e.g. -

Version Imprimable

Université Rennes 2 Nadège Barthélémy : “La sentience est un concept crucial en éthique animale” Nous vous proposons aujourd’hui de découvrir l’exposition virtuelle qui résulte de ce concours, et de lire le témoignage de Nadège Barthélémy, étudiante en Histoire à l’université, et membre de l’association antispéciste depuis 3 ans. Pouvez-vous nous présenter l’association Sentience ? Quel est son fonctionnement ? Nadège Barthélémy. Sentience Rennes est une association étudiante antispéciste. Nous sommes la branche rennaise d'une association appelée "Réseau Sentience". Nous agissons dans les universités afin de sensibiliser les étudiant.es à la cause animale. L’association a plusieurs objectifs parmi lesquels : végétaliser les restaurants universitaires et cafétérias, mettre en lumière la sentience des animaux, révéler la réalité des pratiques d'exploitation, faire connaître la notion de spécisme. Nous sommes composés d'adhérent.es et d'un bureau directionnel, bien que nous essayons au maximum de ne pas instaurer de hiérarchie : par exemple, chacun et chacune est à même de proposer des actions de sensibilisation. Après avoir fait couler beaucoup d’encre, le mot “sentience” est entré dans le Larousse 2020. Selon vous, quels enjeux se cachent derrière l’utilisation de ce terme ? N. B. La sentience est un concept crucial en éthique animale. Le consensus scientifique de Cambridge de 2012 révèle la sentience de la plupart des animaux non-humains. Ce mot a évidemment des implications éthiques. Ce même terme implique nécessairement d'attribuer aux animaux un statut moral. Quels types d’actions sont menées par l’antenne Sentience, ici à Rennes ? Avec quels acteurs rennais travaillez-vous ? N. -

Environment Versus Growth — a Criticism of “Degrowth” and a Plea for “A-Growth”

Ecological Economics 70 (2011) 881–890 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon Analysis Environment versus growth — A criticism of “degrowth” and a plea for “a-growth” Jeroen C.J.M. van den Bergh ⁎ ICREA, Barcelona, Spain Institute for Environmental Science and Technology, and Department of Economics and Economic History, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola), Spain Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, and Institute for Environmental Studies, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands article info abstract Article history: In recent debates on environmental problems and policies, the strategy of “degrowth” has appeared as an Received 21 May 2010 alternative to the paradigm of economic growth. This new notion is critically evaluated by considering five Received in revised form 21 September 2010 common interpretations of it. One conclusion is that these multiple interpretations make it an ambiguous and Accepted 28 September 2010 rather confusing concept. Another is that degrowth may not be an effective, let alone an efficient strategy to Available online 4 November 2010 reduce environmental pressure. It is subsequently argued that “a-growth,” i.e. being indifferent about growth, is a more logical social aim to substitute for the current goal of economic growth, given that GDP (per capita) is Keywords: Consumption a very imperfect indicator of social welfare. In addition, focusing ex ante on public policy is considered to be a Environmental policy strategy which ultimately is more likely to obtain the necessary democratic–political support than an ex ante, Equity explicit degrowth strategy. In line with this, a policy package is proposed which consists of six elements, some GDP paradox of which relate to concerns raised by degrowth supporters. -

Environmental and Natural Resources; Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources Career Cluster

Statewide Program of Study: Environmental and Natural Resources; Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources Career Cluster Principles of Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources Level 1 Wildlife, Fisheries, and Ecology Management/Lab Forestry and Woodland Ecosystems/Lab Level 2 Range Ecology Management/Lab Energy and Natural Resources Technology/Lab Level 3 Advanced Energy and Natural Resource/Lab Practicum in Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources Level 4 Project-Based Research Scientific Research and Design MASTER’S/ Median Annual HIGH SCHOOL/ DOCTORAL Occupations Wage Openings % Growth INDUSTRY CERTIFICATE/ ASSOCIATE’S BACHELOR’S PROFESSIONAL Environmental $53,352 101 32% CERTIFICATION LICENSE* DEGREE DEGREE DEGREE Engineering Technicians Wastewater Board Certified Environmental Environmental Environmental Environmental Engineers $86,757 288 25% Collections, Class Environmental Science Science Science 1 Engineer - Environmental Science $40,268 508 17% Hazardous Waste and Protection Management Technicians, Including Health Environmental Scientists $77,896 644 24% Water Operators, Certified Water Environmental Environmental/ Environmental/ Class D Technologist Studies Environmental Environmental and Specialists, Including Health Health Health Engineering Engineering Zoologists and Wildlife $67,309 45 32% OSHA Hazardous Certified Wildlife, Fish, Wildlife, Fish, Wildlife, Fish, and Biologists Waste Operations Environmental and and Woodlands Woodlands and Emergency Scientist Woodlands Science and Science and Response Science and Management Management Management WORK BASED LEARNING AND EXPANDED Certified in Public Environmental Natural Fishing and Health Engineering Resources Law Fisheries Science LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES Technology/ Enforcement and Management Work Based Learning Environmental and Protective Exploration Activities: Activities: Technology Services Attend summer leadership events Intern at a waste treatment plant Additional industry-based certification information is available on Texas FFA FFA Supervised Agriculture Experience the TEA CTE website. -

Participating in Food Waste Transitions: Exploring Surplus Food Redistribution in Singapore Through the Ecologies of Participation Framework

Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjoe20 Participating in food waste transitions: exploring surplus food redistribution in Singapore through the ecologies of participation framework Monika Rut , Anna R. Davies & Huiying Ng To cite this article: Monika Rut , Anna R. Davies & Huiying Ng (2020): Participating in food waste transitions: exploring surplus food redistribution in Singapore through the ecologies of participation framework, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, DOI: 10.1080/1523908X.2020.1792859 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1792859 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 16 Jul 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjoe20 JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY & PLANNING https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1792859 Participating in food waste transitions: exploring surplus food redistribution in Singapore through the ecologies of participation framework Monika Rut a, Anna R. Davies a and Huiying Ng b aDepartment of Geography, Museum Building, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; bIndependent Scholar, Singapore ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Food waste is a global societal meta-challenge requiring a sustainability transition Food waste; transitions; involving everyone, including publics. However, to date, much transitions research has participation; ecologies of been silent on the role of public participation and overly narrow in its geographical participation; Singapore reach. In response, this paper examines whether the ecologies of participation (EOP) approach provides a conceptual framing for understanding the role of publics within food waste transitions in Singapore. -

2020 Women’S Tennis Association Media Guide

2020 Women’s Tennis Association Media Guide © Copyright WTA 2020 All Rights Reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced - electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying- without the written permission of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Compiled by the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Communications Department WTA CEO: Steve Simon Editor-in-Chief: Kevin Fischer Assistant Editors: Chase Altieri, Amy Binder, Jessica Culbreath, Ellie Emerson, Katie Gardner, Estelle LaPorte, Adam Lincoln, Alex Prior, Teyva Sammet, Catherine Sneddon, Bryan Shapiro, Chris Whitmore, Yanyan Xu Cover Design: Henrique Ruiz, Tim Smith, Michael Taylor, Allison Biggs Graphic Design: Provations Group, Nicholasville, KY, USA Contributors: Mike Anders, Danny Champagne, Evan Charles, Crystal Christian, Grace Dowling, Sophia Eden, Ellie Emerson,Kelly Frey, Anne Hartman, Jill Hausler, Pete Holtermann, Ashley Keber, Peachy Kellmeyer, Christopher Kronk, Courtney McBride, Courtney Nguyen, Joan Pennello, Neil Robinson, Kathleen Stroia Photography: Getty Images (AFP, Bongarts), Action Images, GEPA Pictures, Ron Angle, Michael Baz, Matt May, Pascal Ratthe, Art Seitz, Chris Smith, Red Photographic, adidas, WTA WTA Corporate Headquarters 100 Second Avenue South Suite 1100-S St. Petersburg, FL 33701 +1.727.895.5000 2 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION Women’s Tennis Association Story . 4-5 WTA Organizational Structure . 6 Steve Simon - WTA CEO & Chairman . 7 WTA Executive Team & Senior Management . 8 WTA Media Information . 9 WTA Personnel . 10-11 WTA Player Development . 12-13 WTA Coach Initiatives . 14 CALENDAR & TOURNAMENTS 2020 WTA Calendar . 16-17 WTA Premier Mandatory Profiles . 18 WTA Premier 5 Profiles . 19 WTA Finals & WTA Elite Trophy . 20 WTA Premier Events . 22-23 WTA International Events . -

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010 Contract negotiations, management and meeting arrangements for ASSA meetings are conducted by the American Economic Association. i ASSA_Program.indb 1 11/17/09 7:45 AM Thanks to the 2010 American Economic Association Program Committee Members Robert Hall, Chair Pol Antras Ravi Bansal Christian Broda Charles Calomiris David Card Raj Chetty Jonathan Eaton Jonathan Gruber Eric Hanushek Samuel Kortum Marc Melitz Dale Mortensen Aviv Nevo Valerie Ramey Dani Rodrik David Scharfstein Suzanne Scotchmer Fiona Scott-Morton Christopher Udry Kenneth West Cover Art is by Tracey Ashenfelter, daughter of Orley Ashenfelter, Princeton University, former editor of the American Economic Review and President-elect of the AEA for 2010. ii ASSA_Program.indb 2 11/17/09 7:45 AM Contents General Information . .iv Hotels and Meeting Rooms ......................... ix Listing of Advertisers and Exhibitors ................xxiv Allied Social Science Associations ................. xxvi Summary of Sessions by Organization .............. xxix Daily Program of Events ............................ 1 Program of Sessions Saturday, January 2 ......................... 25 Sunday, January 3 .......................... 26 Monday, January 4 . 122 Tuesday, January 5 . 227 Subject Area Index . 293 Index of Participants . 296 iii ASSA_Program.indb 3 11/17/09 7:45 AM General Information PROGRAM SCHEDULES A listing of sessions where papers will be presented and another covering activities such as business meetings and receptions are provided in this program. Admittance is limited to those wearing badges. Each listing is arranged chronologically by date and time of the activity; the hotel and room location for each session and function are indicated. CONVENTION FACILITIES Eighteen hotels are being used for all housing. -

Green Economy Or Green Utopia? Rio+20 and the Reproductive Labor Class

Green Economy or Green Utopia? Rio+20 and the Reproductive Labor Class Ariel Salleh University of Sydney [email protected] Sociologists use the concept of class variously to explain and predict people's relation to the means of production, their earnings, living conditions, social standing, capacities, and political identification. With the rise of capitalist globalization, many sociologists focus on the transnational ruling class and new economic predicaments faced by industrial workers in the world-system (see, for example, Robinson and Harris 2000). Here I will argue that to understand and respond to the current global environmental crisis, another major class formation should be acknowledged - one defined by its materially regenerative activities under "relations of reproduction" (Salleh 2010). The salience of this hypothetical third class is demonstrated by the 2012 United Nations Rio+20 summit and its official "green economy" negotiating text The Future We Want (UNCSD 2012). Clearly, the question that begs to be asked is - who is the "we" in this international document, and whose "utopia" does it serve? Part of the answer is found in a recent G20 media release, suggesting that "current high energy prices open policy space for economic incentives to renewables [...] investors are looking for alternatives given the low interest rates in developed countries, a factor that presents an opportunity for green economy projects” (Calderon 2012). The UN, together with the transnational capitalist class, looks to technology and new institutional architectures to push against the limits of living ecologies, and these measures are given legitimation as "economic necessity." Yet empirically, it is peasants, mothers, fishers and gatherers working with natural thermodynamic processes who meet everyday needs for the majority of people on earth. -

Green Growth Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: the Alternative Solution for Achieving the Balance Between Both the Natural and the Economic System

sustainability Editorial Green Growth Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: The Alternative Solution for Achieving the Balance between Both the Natural and the Economic System Diego A. Vazquez-Brust 1,2 and José A. Plaza-Úbeda 3,* 1 Portsmouth Faculty of Business and Law, Richmond Building, Portland Street, Portsmouth P01 3DE, UK; [email protected] 2 Production Engineering Department, Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Florianópolis 88040-900, SC, Brazil 3 Economics and Business Department, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] 1. Introduction “We are ethically obliged and incited to think beyond what are treated as the realistic limits of the possible” (Judith Butler, 2020) The existence of an imbalance between our planet’s reserves of resources and the conditions necessary to maintain high levels of economic growth is evident [1]. The limitation of natural resources pushes companies to consider the possibility of facing critical situations in the future that will make it extremely difficult to reconcile economic Citation: Vazquez-Brust, D.A.; and sustainable objectives [2]. Plaza-Úbeda, J.A. Green Growth In this context of dependence on an environment with finite resources, there are Policy, De-Growth, and Sustainability: growing interests in alternative economic models, such as the Circular Economy, oriented to The Alternative Solution for the maximum efficient use of resources [3–5]. However, the Circular Economy approach is Achieving the Balance between Both still very far from the reality of industries, and the depletion of natural resources continues the Natural and the Economic System. undeterred [6]. It is increasingly necessary to explore alternative approaches to address the Sustainability 2021, 13, 4610.