Physical–Mechanical and Mineralogical Properties of Fired Bricks of the Archaeological Site of Harran, Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey

Başak Ekim Akkan, Mehmet Baki Deniz, Mehmet Ertan Photography: Başak Erel Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey spf sosyal politika forumu . Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey Published as part of the Project for Developing Comprehensive Social Policies for Roma Communities Başak Ekim Akkan, Mehmet Baki Deniz, Mehmet Ertan Photography: Başak Erel . Editor: Taner Koçak Cover photograph: Başak Erel Cover and page design: Savaş Yıldırım Print: Punto Print Solutions, www.puntops.com First edition, November 2011, Istanbul ISBN: 978-605-87360-0-9 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without the written permission of EDROM (Edirne Roma Association), Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum and Anadolu Kültür. COPYRIGHT © November 2011 Edirne Roma Association (EDROM) Mithat Paşa Mah. Orhaniye Cad. No:31 Kat:3 Edirne Tel/Fax: 0284 212 4128 www.edrom.org.tr [email protected] Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum Kuzey Kampus, Otopark Binası Kat:1 No:119 34342 Bebek-İstanbul Tel: 0212 359 7563-64 Fax: 0212 287 1728 www.spf.boun.edu.tr [email protected] Anadolu Kültür Cumhuriyet Cad. No:40 Ka-Han Kat:3 Elmadağ 34367 İstanbul Tel/Fax: 0212 219 1836 www.anadolukultur.org [email protected] The project was realized with the financial support of the European Union “European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR)” program. The Swedish Consulate in Istanbul also provided financial support to the project. The contents of this book do not reflect the opinions of the European Union. -

Bölüm Adı : SANAT TARİHİ

Bölüm Adı : SANAT TARİHİ Tüm Dönemler EDSTN 217 - Arkeoloji Anadolu Uyg-III - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Paleolitik /Epipaleolitik Dönem ve Özellikleri , Anadolu dışındaki önemli Paleolitik Merkezler(Alatamira ve Lascaux Mağaraları) , Anadoludaki Paleolitik dönem mağaralarından örnekler( Karain, Öküzini Yarımburgaz, Dülük, Palanlı Kaletepe vd.) , Anadoludaki Paleolitik Dönem yerleşmeleri , Mezolitik Çağ ve bu döneme ait yerleşim alanları , Aseramik /Erken Neolitik Çağ Yerleşmeleri , Madenin kullanımı , Erken Neolitik Dönem (seramiksiz dönem) ve Natuf Kültürü , Erken Neolitik Çağ Yerleşmeleri (Göbeklitepe, Hallan Çemi,Nevala Çori, Çayönü,Aşıklı höyük , Çayönü ve madenin kullanımı konut mimarisinin gelişimi , Çatalhöyük Seramiksiz ve seramikli dönem , Çatal Höyükte Konut Mimarisi , Ölü Gömme ve Ata Kültü geleneği , Çatalhöyük Konutlarındaki Kültsel yapılar ve din olgusu , EDSTN 449 - Çağdaş Sanat-I - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 5 Neoklasizm ve realizm , Romantizm , Empresyonizm , Sembolizm , Ekspresyonizm , Bauhaus , Fovizm , ARA SINAV , Kübizm , Fütürizm , Dadaizm , Konstrüktivizm , Süpremaztizm , De Stijl Grubu ve Sürrealizm , EDSTN 219 - Ortaçağ İslam Sanatı-III - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Karahanlı Dönemi hakkında genel bilgi ve yapı grupları ile genel özellikleri , Karahanlı Dönemi Türkistan Camileri (Çilburç, Başhane, Dehistan,) , Talhatan Baba, Buhara Namazgah Magaki Attari camileri , Karahanlı Minareleri Burana, Kalan minareleri) , Can kurgan Vabkent minareleri , Karahanlı türbeleri (Tim Arap Ata, Ayşe Bibi) , Özkent Türbeleri, Şeyh Fazıl Türbesi , Karahanlı Hanları (Manakeldi, Daye Hatun) , Akçakale, Dehistan Hanları , Karahanlı Dönemi taşınabilir eserlerden örnekler , Gazneli dönemi minareleri (III. Mesut Sultan Mahmut Minareleri) , Gazneli Türbeleri (Aslancazip, Babahatim) , Gazneli dönemi sarayları (Leşger-i Bazar, III. Mesut) , Gazneli dönemi taşınabilir eserlerden örnekler , EDSTN 237 - Bizans Sanatı I - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Byzansolojinin ortaya çıkışı , anlamı, gelişmi. -

The Current Volume 26

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 11-3-2015 The urC rent Volume 26 : Issue 11 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The urC rent Volume 26 : Issue 11" (2015). The Current. 498. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/498 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Student-Run Newspaper of Nova Southeastern University • November 3, 2015 | Vol. 26, Issue 11 | nsucurrent.nova.edu How to handle stress Domestic violence in the Say “Hello” to Adele’s new Perplexed over parking? NFL single P. 6 P. 10 P. 12 P. 15 By: Li Cohen and Nicole Cocuy Shark du Soleil takes over NSU To celebrate another year at NSU, Student In a study conducted at Purdue University, Events and Activities Board will host the Shark it was found that students who are involved and du Soleil Homecoming Week from Nov. 7 to active on their college campuses academically Nov. 13. perform better than those who only go to classes. Homecoming Week is a tradition at NSU “This is NSU,” Roberts said. “This is what that consists of a week-long celebration. During we have, and all you can do is come out and try this week, the NSU community gathers to to make the best experience out of it and make it celebrate Shark pride through activities and the fun. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

Tire (İzmir)'De Turizm Türlerini Bütünleştirme Olanakları: Kültür

Tire (İzmir)’de Turizm Türlerini Bütünleştirme Olanakları: Kültür Turizmi, Kırsal Turizm, Agroturizm ve Gastronomi Turizmi 153 Tire (İzmir)’de Turizm Türlerini Bütünleştirme Olanakları: Kültür Turizmi, Kırsal Turizm, Agroturizm ve Gastronomi Turizmi Emre ATABERKa a Ege Üniversitesi, Bergama Meslek Yüksekokulu, Turizm ve Otel İşletmeciliği Programı, Bergama, İZMİR Öz Günümüzde turizm türleri çok artmış, onlara ait mekânlar da çok çeşitlenmiştir. Turizmde bütünleştirme yoluyla, hem rekabet gücü zayıf destinasyonların tanıtım ve pazarlamasına katkı verilmekte hem de turizm türlerinin birbirini tamamlaması sağlanmaktadır. Bu çalışmanın amacı; Tire ilçesinde kültür turizmi, kırsal turizm, agroturizm ve gastronomi turizminin bütünleştirilmesi, birbirini tamamlayabilme ve aralarında bütünleşebilme olanaklarını ortaya çıkarmaktır. Bu doğrultuda adı geçen turizm türleri arasında benzerlikler, ilişkiler, etkileşimler ve geçişlerin var olup olmadığı araştırılmıştır. Çalışmada, sosyal bilimlerin niteliksel yöntemleri kapsamında veri analizi, gözlem, görüşme ve alan araştırmasına gidilmiştir. Çalışmada önce kültür turizmi, kırsal turizm, agroturizm ve gastronomi turizmi kuramsal olarak işlenmiştir. Daha sonra Tire ilçesinin doğal ve kültürel özellikleri ana hatlarıyla açıklanmıştır. Bu temel üzerinde adı geçen turizm türlerinin bir bütün olarak Tire’de nerelerde ve nasıl geliştirilebileceği ortaya konmuş, bazı örnekler verilmiş ve öneriler geliştirilmiştir. Elde edilen bulgulara göre; Tire’nin kentsel ve kırsal çekiciliklerinin, tarım ve mutfak özelliklerinin, bir bütün halinde turizme kazandırılabileceği sonucu ortaya çıkmıştır. Bunun için Tire’de turizmle ilgili bir örgütlenmeye gidilmeli, plan-proje, tanıtım ve pazarlama çalışmaları yapılmalıdır. Ayrıca kültürel yapılar, pazar, mutfak ve el sanatları Tire’nin marka değerleri olarak öne çıkarılmalı ve muhakkak konaklamalı paket turlar yaratılmalıdır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Turizm Türleri, Bütünleştirme, Tire. Abstract Today, many types of tourism have increased and also places that belong to them have diversified. -

4920 10 Cc D22-01 2Pac D43-01 50 Cent 4877 Abba 4574 Abba

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA TRECHO DA MÚSICA 4920 10 CC I´M NOT IN LOVE I´m not in love so don´t forget it 19807 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time there was no way of D22-01 2PAC DEAR MAMA You are appreciated. When I was young 9033 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older 2578 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down 9072 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still D36-01 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA I drove by all the places we used to hang out D36-02 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEARTBREAK GIRL You called me up, it´s like a broken record D36-03 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART Everybody´s got their demons even wide D36-04 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT Simmer down, simmer down, they say we D43-01 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Go, go, go, go, shawty, it´s your birthday D54-01 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN I walk along the avenue, I never thought I´d D35-40 A TASTE OF HONEY BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE If you´re thinkin´ you´re too cool to boogie D22-02 A TASTE OF HONEY SUKIYAKI It´s all because of you, I´m feeling 4970 A TEENS SUPER TROUPER Super trouper beams are gonna blind me 4877 ABBA CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what´s wrong 4574 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Yeah! You can dance you can jive 19333 ABBA FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando D17-01 ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME Half past twelve and I´m watching the late show D17-02 ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR No more champagne and the fireworks 9116 ABBA I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing… -

A New Approach for Defining the Conservation Status of Early Republican Architecture Case Study: Primary School Buildings in Izmir

A NEW APPROACH FOR DEFINING THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF EARLY REPUBLICAN ARCHITECTURE CASE STUDY: PRIMARY SCHOOL BUILDINGS IN İZMİR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FATMA NURSEN KUL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN RESTORATION IN ARCHITECTURE MARCH 2010 Approval of the thesis: A NEW APPROACH FOR DEFINING THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF EARLY REPUBLICAN ARCHITECTURE CASE STUDY: PRIMARY SCHOOL BUILDINGS IN IZMIR submitted by FATMA NURŞEN KUL in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Architecture, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Canan Özgen ______________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Güven Arif Sargın ______________ Head of the Department, Architecture Assoc. Prof. Dr. Emre Madran ______________ Supervisor, Department of Architecture, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elvan Altan Ergut ______________ Co-Supervisor, Department of Architecture, METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. C. Abdi Güzer ______________ Department of Architecture, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Emre Madran ______________ Department of Architecture, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Can Binan ______________ Department of Architecture, YTU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Suavi Aydın ______________ Department of Anthropology, HU Asst. Prof. Dr. Güliz Bilgin Altınöz ______________ Department of Architecture, METU Date: 15.03.2010 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash Kommt Im August Auf

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash kommt im August auf „Made Of Bricks“-Jubiläumstour Wenn das kein Grund zum Feiern ist: Vor zehn Jahren kam ein Album heraus, das die Musikszene in Großbritannien nachhaltig veränderte: Durch „Made Of Bricks“, die platinveredelte Debütplatte von Kate Nash, war klar geworden, dass sich junge Frauen ihren Platz in der Gesellschaft (und in der Musikindustrie) ganz anders behaupten wollen. Eine neue Art von Feminismus hielt Einzug. Gleichzeitig war Nash auch eines der ersten so genannten Internetphänomene. Durch ihre auf Myspace veröffentlichten Lieder wie „Caroline’s A Victim“ wurde sie rasend schnell bekannt - und „Foundations“, die erste Single aus dem Album, ging komplett durch die Decke. Weil ihre Fans schon alle Türen einrannten, musste „Made Of Bricks“ sogar fünf Wochen vor dem geplanten Termin veröffentlicht werden. „Ich fühle mich wie eine Außenseiterin, die sich gerade irgendwo reingeschlichen hat“, sagte die junge Frau damals. Inzwischen ist es zwar noch immer nicht Standard, aber doch sehr viel selbstverständlicher geworden, dass Frauen ihre Songs selbst schreiben, ihre Instrumente selbst spielen, die Kontrolle über ihre Musik weitgehend in ihren eigenen Händen halten. Ganz schön stark für eine 20-Jährige, die im Anschluss nicht nur aus dem Stand den Brit-Award als British Female Solo Artist und etliche weitere Auszeichnungen abräumte, sondern auch weiterhin sehr erfolgreich Musik macht. Darüber hinaus engagiert sie sich sozial: Sie rief gemeinsam mit Billy Bragg, Blur, Radiohead und anderen Künstlern die Featured Artists Coalition ins Leben, die sich für die Rechte von Musikern im digitalen Zeitalter einsetzt. -

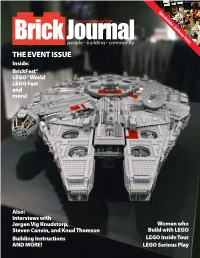

THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: Brickfest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and More!

Epic Builder: Anthony Sava THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: BrickFest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and more! Also: Interviews with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, Women who Steven Canvin, and Knud Thomson Build with LEGO Building Instructions LEGO Inside Tour AND MORE! LEGO Serious Play Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Urban Conservation Policies and Plans for a World Heritage Site Case: Antique Pergamon City and Its Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape

IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering PAPER • OPEN ACCESS Related content - Evaluation of the Conservation of Modern Urban Conservation Policies and Plans for a World Architectural Heritage through Ankara’s Public Buildings Heritage Site Case: Antique Pergamon City and its Nevin Turgut Gültekin - Urban landscape architecture design Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape under the view of sustainable development WeiLin Chen To cite this article: Mehmet Tunçer 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 245 082032 - Whose Sense of Place? Re-thinking Place Concept and Urban Heritage Conservation in Social Media Era Christin Dameria, Roos Akbar and Petrus Natalivan Indradjati View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 95.183.183.73 on 18/12/2019 at 08:23 WMCAUS IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering1234567890 245 (2017) 082032 doi:10.1088/1757-899X/245/8/082032 Urban Conservation Policies and Plans for a World Heritage Site Case: Antique Pergamon City and its Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape Mehmet Tunçer 1 1 Cankaya University, Faculty of Architecture, City and Regional Planning Dep. Balgat Campus, 06530 Balgat, Ankara, Turkey [email protected] Abstract. Izmir's Pergamon (Bergama) Antique City and Its Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape entered the UNESCO World Heritage List with the participation of 21 countries in the 38th World Heritage Committee Meeting held in Doha, Qatar's capital in between 15 - 25 June 2014. Bergama became the 999th WORLD HERITAGE. Bergama, which has been in operation since 2010, has entered the list as a Multi-layered Cultural Landscape Area. The main purpose of this paper will explain and summarize of urban and archaeological conservation efforts for Pergamon since 1992 to 2014. -

& Photography Turkish Culture

JOIN TURKEY Photography Turkish& Culture September 8-25, 2021 Tour Leader: Mark Meulemans Join me in this magical trip through Turkey, enjoy the enchanting coasts and get submerged in its ancient history. 'No prior expertise in photography necessary' organized by TURKEY: Photography & Turkish Culture / September 8-25, 2021 MARK MEULEMANS elgian born, living in Turkey Cappadocia Bfor several years, he is the photographer behind the the awarded cultural travel website Sep 10 Fri Istanbul – Cappadocia slowtravelguide.com After the breakfast visit to Spice Bazaar, take a private Boat Tour along the Bosphorus, seeing the European and Asian shores of Istanbul including “Turkey is a vibrant, unique place to Bosphorus Bridge, Beyoglu streets and Galata Tower. Transfer to Istanbul be, especially for those interested in Aiprort for fly to Kayseri. Meet at Kayseri airport, drive to Cappadocia, where photography. It will be a cultural exchange, and I think you’re nature has scoured surrealistic moonscape shapes, and the persecuted going to be amazed at how special the experience is. Christians dug underground cities and churches during the 9th century. Check-in to your hotel. Overnight in Cappadocia. (B,D) I love traveling and photographing here. Turkey is a country with generous, friendly people, great food and drinks, timeless architecture and a rich history. I will assist and guide you in an Antique Sites Tour part 2 easy way through several photo techniques and advise you how to approach different sceneries. Sep 11 Sat Cappadocia Optional: Hot Air Baloon Ride (05:30 am – 07.30am). Back to the hotel for Join me in this magical trip through Turkey, enjoy the berakfast. -

Assessing Alluvial Fan of Bergama Using High Resolution DEM Generated from Airborne Lidar Data

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 13 September 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202009.0260.v1 Article Assessing Alluvial Fan of Bergama Using High Resolution DEM Generated from Airborne LiDAR Data Beycan Hocao˘glu 1,†,‡ , Müge A˘gca 2,‡ 1 Izmir˙ Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi; beycan.hocao˘[email protected] 2 Izmir˙ Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +90-232-329 35 35 / 8520 † Current address: Izmir˙ Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi, Sosyal ve Be¸seriBilimler Fak. Co˘grafyaBölümü, Çi˘gli Izmir˙ / TÜRKIYE˙ ‡ These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Topography represented by high resolution digital elevation models are able to inform past and present morphological process on the terrain. High resolution LiDAR data taken by the General Directorate of Map at the surroundings of the Bergama city shows great opportunities to understand the morphological process on alluvial fan on which the city is located and the flood plain of Bakırçay river near the alluvial fan. In this paper the LiDAR data collected in 2015 have been used to create DEM’s to understand the geomorphological evolution of the alluvial fan and the flood plain around it. Since the proximal roots and medial parts of the alluvial fan have been the scene for a long human settlement most topographical traces of the morphological process have been distorted. Nevertheless, the traces of past and present morphological process at the distal fan which consist the contact zone with the flood plain are very clear on the DEM created from LiDAR data. The levees and some old courses of Bergama and Bakırçay rivers have been shown on the maps which are also important to understand the ancient roads which follows these levees.