Uwajimaya and Uwajimaya Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tomio Moriguch, Executive Officer of Uwajimaya, Inc

Tomio Moriguch, Executive Officer of Uwajimaya, Inc.: Integrating American and Japanese Business Models Moriguch, Tomio My name is Jess Van Duzer and I am the dean of the School of Business and Economics. This is the first of our three Dean’s Speaker Series for this year. We are very glad you could be here. I suspect many of you are here as part of a class. You should know that each of these three speaker series are open to you at all times, whether or not your class is asking you to come. What we try to do is bring some of the leading business leaders from our community here so that you have a chance to get to know them in a relatively intimate way. They will tell you a little bit about their background, a little bit about their company. Really it is a time for you to ask them questions. Our hope in doing all of this is that it will help you take some of the stuff we are trying to teach in classes and see how it shows up on the ground. So I encourage you to be thinking as you listen of questions you might want to ask or you might want to say. In our class we are always told this but how does that really work and is my professor nuts? So however you want to phrase your questions it will be fine. We are glad you are here. I am going to ask Mark if you would do the introductions. -

Isrd 187/15 Minutes for the Meeting Of

ISRD 187/15 MINUTES FOR THE MEETING OF TUESDAY, September 22, 2015 Time: 4:30pm Place: Bush Asia Center 409 Maynard Avenue S. Basement meeting room Board Members Present Staff Ben Grace Rebecca Frestedt Carol Leong, Vice Chair Melinda Bloom Miye Moriguchi Martha Rogers, Chair Joann Ware Marie Wong Absent 92215.1 APPROVAL OF MINUTES August 25, 2015 MM/SC/BG/CL 3/0/2 Minutes approved. Mmes. Wong and Rogers abstained. 092215.2 CERTIFICATES OF APPROVAL 092215.21 Publix 504 5th Ave. S. Applicant: Molly Martin, Blanton Turner Ms. Frestedt explained the proposed installation of four (4) construction banners. Dimensions: 5’h x 10’w. Exhibits included photographs and material sample. She said the signs will be attached to scaffolding. Estimated duration: Oct. 2015 – January 2016. The Publix and Uwajimaya Warehouse buildings are located within the Asian Character Design District. She said that banner material is generally not preferred for building or business signs; however, due to the subdued nature of the graphics, the temporary nature of the construction at the site and the fact that the signs will be installed on scaffolding rather than on the building, staff does not have objections to this proposal. Administered by The Historic Preservation Program The Seattle Department of Neighborhoods “Printed on Recycled Paper” Molly Martin, Blanton Turner, explained that the four mesh signs will hang 8’ above the sidewalk and will be attached to scaffolding with zip ties. She said the signs will be up October through December when the scaffolding comes down. She provided an artwork mock up. Responding to questions she said the size is 5’ x 10’. -

A Guide for Immigrants, Refugees and Other Newcomers

A guide for immigrants, refugees and other newcomers Photo By Katharine Kimball Welcome Home.We believe that relocating to a new city can be a wonderful and exciting time but also adjusting to a new place and perhaps a new language and culture can seem overwhelming at first. We hope that by providing basic information about your new city, as well as listing agencies in the area that provide many varied services that may be beneficial, you will soon come to feel at home in the city of Beaverton. This guide lists only a sampling of the variety of resources available to you; it is not an extensive list and is not meant to recommend any one resource over another. It is intended to help you explore the city and all that it has to offer. Beaverton is the sixth most populous city in the state of Oregon. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of July 2017 Beaverton’s population was 97,514. One in five Beaverton residents was born outside the United States, and more than 100 different languages are spoken by families in the Beaverton School District. Beaverton was incorporatedd as a city in 1893. Beaverton officially became a Welcoming City in 2015, expressing its commitment to welcoming newcomers from all This guide was compiled by backgrounds and promoting cross-cultural relationships. In 2017, two committed volunteers the City Council also voted unanimously to declare Beaverton a who live in Beaverton and Sanctuary City. believe that every person is welcome in this diverse community and should have the opportunity to find the services and support they need to feel truly at home in the city of Beaverton. -

The Economic Impact of a Walmart Store in the Skyway Neighborhood of South Seattle

The Economic Impact of a Walmart Store in the Skyway Neighborhood of South Seattle Christopher S. Fowler PhD. • C.S. Fowler Consulting LLC April 5, 2012 This report was produced by C.S. Fowler Consulting LLC for Puget Sound Sage. Special thanks to the United Food and Commercial Workers 21 for 2009 wage and contract data. Over the course of 2012 Puget Sound Sage will be releasing a series of briefs and reports examining the impact of service sector industries on the Puget Sound regional economy. Author: Christopher S. Fowler PhD. C.S. Fowler Consulting LLC (206) 920-1686 [email protected] Executive Summary Recent analyses conducted in support of • Although the direct impacts resulting Walmart store development plans in the from the renovation of the site contribute Pacific Northwest are irreparably flawed by a net positive effect of $2.67 million in their failure to address offsetting losses in economic output and $1.12 million in employment and employment income that labor income during construction, this is would be the result of new store development not nearly enough to offset other changes in the saturated retail environments for which over the twenty year life of the project. these projects are proposed. • The net present value of all changes Following standard practice in regional estimated in our Base scenario over a 20 analysis, we consider the redistribution year project lifespan is projected to be in consumer sales that would occur if a a net loss of $13.07 million in economic new Walmart “neighborhood market” of output and a loss of $14.51 million in approximately 40,000 square feet were to labor income. -

23Rd Avenue Action Plan Community Comments

23rd Avenue Action Plan: Union – Cherry – Jackson Phase 1 Consolidated Community Comments (April community workshop, online surveys, in-person interviews, POEL workshops) Great Business Destinations Good Needs Work/Desired Ideas Shops and Services Where do you go for goods and services, and why? • Where do you go for goods and services, and why? • More kid friendly places/commercial locations How do you get there? What goods and services are How do you get there? What goods and services are • missing as your neighborhood grows? missing as your neighborhood grows? • I go to the hair store on Jackson and the Safeway • Downtown or Bellevue, history of shopping and on Madison. I drive my car. I frequent those convenience. Drive or bus. businesses often because the parking is very • Capitol Hill, Sodo, U-district by bicycle or car. I convenient and free. have to travel to either Factoria or Northgate. • Fremont (PCC), Madison Park (hardware store, • Cap hill, first hill, Renton, Sodo. Pharmaca, Bert's) Montlake (Mont's, Jay's, • Downtown, Capitol Hill and the rainier Valley. I library). I go to 23rd and Jackson for most get there by bus and car. Missing services- everything. I like to walk to Red Apple or Taco del drugstore in union/cherry. Bakery. Mar. • Capitol Hill, more variety. • I travel to the 15th Avenue core or Rainier Valley • Mostly car. There isn't much that we walk to and by car. we like to walk. Columbia city is a favourite. Go to • Capitol Hill--QFC, Trader Joes, Madison Market; dinner check out some shops and go see a movie get there by driving; Local markets for the diverse and then grab some ice cream. -

Protocols* (Local Environment for Activity and Nutrition-- Geographic Information Systems)

LEAN-GIS Protocols* (Local Environment for Activity and Nutrition-- Geographic Information Systems) Version 2.0, December 2010 Edited by Ann Forsyth Contributors (alphabetically): Ann Forsyth, PhD, Environmental Measurement Lead Nicole Larson, Manager, EAT-III Grant Leslie Lytle, PhD, PI, TREC-IDEA and ECHO Grants Nishi Mishra, GIS Research Assistant Version 1 Dianne Neumark-Sztainer PhD, PI, EAT-III Pétra Noble, Research Fellow/Coordinator, Versions 1.3 David Van Riper, GIS Research Fellow Version 1.3/Coordinator Version 2 Assistance from: Ed D’Sousa, GIS Research Assistant Version 1 * A new edition of Environment, Food, and Yourh: GIS Protocols http://www.designforhealth.net/resources/trec.html A Companion Volume to NEAT-GIS Protocols (Neighborhood Environment for Active Travel),Version 5.0, a revised edition of Environment and Physical Activity: GIS Protocols at www.designforhealth.net/GISprotocols.html Contact: www.designforhealth.net/, [email protected] Preparation of this manual was assisted by grants from the National Institutes of Health for the TREC--IDEA, ECHO, and EAT--III projects. This is a work in progress LEAN: GIS Protocols TABLE OF CONTENTS Note NEAT = Companion Neighborhood Environment and Active Transport GIS Protocols, a companion volume 1. CONCEPTUAL ISSUES ............................................................................................................5 1.1. Protocol Purposes and Audiences ........................................................................................5 1.2 Organization of the -

Groundwork for the King County Food and Fitness Initiative

Food for Thought: Groundwork for the King County Food & Fitness Initiative A Report by the University of Washington Department of Urban Design and Planning Summer Studio 2008 food & fitness A NATIONAL INITIATIVE OF THE W.K. KELLOGG FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Executive Summary Chapter One: Built Environment Chapter Two: Community Food System Assessment Appendix to Chapter One Food for Thought: Groundwork for the King County Food & Fitness Initiative Executive Summary – Page 1 [page intentionally left blank] Food for Thought: Groundwork for the King County Food & Fitness Initiative Executive Summary – Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was funded through assistance from: W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Food & Fitness Initiative Prepared for: King County Food & Fitness Initiative Special Thanks to: The diverse community of Delridge and White Center, Café Rozella, Delridge Neighborhoods Development Association, Public Health – Seattle & King County, West Seattle Food Bank, White Center Community Development Association, White Center Food Bank, Youngstown Cultural Center and the following individuals: Maggie Anderson (Public Health), Derek Birnie (DNDA), Roxana Chen (Public Health), (David Daw (WCCDA), Randy Engstrom (Youngstown) and Alberto Mejia (Youngstown). Special thanks to the youth of Youngstown who inspired the title of this report. Prepared by: University of Washington Department of Urban Design and Planning Graduate Students Eddie Hill Joyce Chen Don Kramer Jennifer Lail Kara Martin Torence Powell Faculty Branden Born -

Group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data

group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data Business_ID Program Identifier PR0088142 MOD PIZZA PR0089582 ANCESTRY CELLARS, LLC PR0046580 TWIN RIVERS GOLF CLUB INC PR0042088 SWEET NECESSITIES PR0024082 O'CHAR CROSSROADS PR0081530 IL SICILIANO PR0089860 ARENA AT SEATTLE CENTER - Main Concourse Marketplace 7 PR0017959 LAKE FOREST CHEVRON PR0079629 CITY OF PACIFIC COMMUNITY CENTER PR0087442 THE COLLECTIVE - CREST PR0086722 THE BALLARD CUT PR0089797 FACEBOOK INC- 4TH FLOOR PR0011092 CAN-AM PIZZA PR0003276 MAPLE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PR0002233 7-ELEVEN #16547P PR0089914 CRUMBL COOKIES PR0089414 SOUL KITCHEN LLC PR0085777 WILDFLOWER WINE SHOP & BISTRO PR0055272 LUCKY DEVIL LATTE PR0054520 THAI GINGER Page 1 of 239 09/29/2021 group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data PR0004911 STOP IN GROCERY PR0006742 AMAZON RETAIL LLC - DELI PR0026884 Seafood PR0077727 MIKE'S AMAZING CAKES PR0063760 DINO'S GYROS PR0070754 P & T LUNCH ROOM SERVICE @ ST. JOSEPH'S PR0017357 JACK IN THE BOX PR0088537 GYM CONCESSION PR0088429 MS MARKET @ INTENTIONAL PR0020408 YUMMY HOUSE BAKERY PR0004926 TACO BELL #31311 PR0087893 SEATTLE HYATT REGENCY - L5 JR BALLROOM KITCHEN & PANTRIES PR0020009 OLAFS PR0084181 FAIRMOUNT PARK ELEMENTARY PR0069031 SAFEWAY #1885- CHINA DELI / BAKERY PR0001614 MARKETIME FOODS - GROCERY PR0047179 TACO BELL PR0068012 SEATTLE SCHOOL SUPPORT CENTER/ CENTRAL KITCHEN PR0084827 BOULEVARD LIQUOR PR0006433 KAMI TERIYAKI PR0052140 LINCOLN HIGH SCHOOL Page 2 of 239 09/29/2021 group Based on Food Establishment Inspection Data PR0086224 GEMINI FISH TOO -

Document.Pdf

AN EASTSIDE URBAN OASIS. Bellefield Office Park offers a distinctive 15-building campus within 65-acres of wooded and landscaped grounds. Located minutes from downtown Bellevue, Bellefield is exceptionally well located and easy to access. Both high-profile corporate companies and small private businesses call Bellefield home. BUILDING FEATURES Easily Accessible. Quietly Productive. An incomparable setting calls for exceptional amenities. Bellefield delivers with an on-site conference center, fitness facility and café. • 15-building campus with one, two and • Fitness center three-story buildings • Café • 3.5/1,000 SF parking ratio; free surface • Skylights and atrium lobbies parking; covered parking available • FedEx and UPS drop boxes • On-site property management • Security patrol • Conference facility with training room; large and small board rooms; catering kitchen • Walking/jogging path Fifteen Buildings, Each With Its Own Distinctive Appeal. AREA AMENITIES Bellefield’s expansive park-like campus belies its close proximity to all the conveniences and services you’d expect to find in an urban neighborhood. • Bellevue Square and The Shops • Area hotels include The Westin, Hotel Bellevue, at The Bravern Hyatt Regency, Marriott, Hilton and more • Dry cleaning • LA Fitness and 24-Hour Fitness • Restaurants and coffee shops • Banks and ATMs • Childcare • FedEx Office and The UPS Store • QFC and Safeway • Bellevue Post Office • Bellevue Club NE 12TH ST 19 12 10 NE 8TH ST 7 18 13 LOCATION/MAP 9 4 8 24 29 6 NE 4TH ST 30 Downtown Access 28 NE AVE 116TH 11 with Suburban 5 25 26 27 Convenience MAIN ST 15 Bellefield Office Park is just a Bellevue 405 right turn away from I-405, just 22 south of downtown Bellevue 17 23 with easy access to I-90 from L 16 21 AKE HILLS CON I-405 or Bellevue Way. -

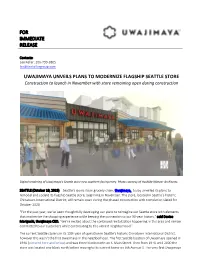

UWAJIMAYA UNVEILS PLANS to MODERNIZE FLAGSHIP SEATTLE STORE Construction to Launch in November with Store Remaining Open During Construction

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: Lee Keller, 206-799-3805 [email protected] UWAJIMAYA UNVEILS PLANS TO MODERNIZE FLAGSHIP SEATTLE STORE Construction to launch in November with store remaining open during construction Digital rendering of Uwajimaya's Seattle store new southern-facing entry. Photo courtesy of Hoshide Wanzer Architects. SEATTLE (October 10, 2019) – Seattle’s iconic Asian grocery chain, Uwajimaya, today unveiled its plans to remodel and update its flagship Seattle store, beginning in November. The store, located in Seattle’s historic Chinatown-International District, will remain open during the phased construction with completion slated for October 2020. “For the past year, we’ve been thoughtfully developing our plans to reimagine our Seattle store with elements that modernize the shopping experience while keeping the connection to our 90-year history,” said Denise Moriguchi, Uwajimaya CEO. “We’re excited about the continued revitalization happening in this area and remain committed to our customers while contributing to this vibrant neighborhood.” The current Seattle store is in its 19th year of operation in Seattle’s historic Chinatown International District, however this wasn’t the first Uwajimaya in the neighborhood. The first Seattle location of Uwajimaya opened in 1946 (pictured here and below) and was three blocks north on S. Main Street. Then from 1970 until 2000 the store was located one block north before moving to its current home on 5th Avenue S. The very first Uwajimaya store was opened in Tacoma, Washington in the 1930s before WWII. The family had to leave Tacoma for Tule Lake Internment Camp during the war and settled in Seattle to start again after the war. -

Oregon Redemption Centers Albany Beaverton

Oregon Redemption Centers and Associated Retailers (5,000 or more sq ft in size) ZONE 1 ZONE 2 EXEMPT** DEALER REDEMPTION CENTERS*** FULL SERVICE PARTICIPATING RETAILERS PARTICIPATING RETAILERS (accept 144 containers) (accept 24 containers) REDEMPTION CENTERS (accept 0 containers) (accept 24 containers) 0 - 2.0 miles radius Albany from redemption center No Zone 2 Zone 1 No Zone 2141 Santiam Hwy SE Albany Grocery Outlet Albany East Liquor Store 1103 ALOHA 1950 14th Ave SE 2530 Pacific Blvd SE Albertsons #3557 approved 6/18/2015 Big Lots #4660 Dollar Tree #1508 6055 SW 185th 2000 14th Ave SE, Ste 102 1307 Waverly Dr SE Bi-Mart #606 Lowe's #3057 BEAVERTON 2272 Santiam Hwy 1300 9th Ave SE Fred Meyer #482 Costco #0682 15995 SW Walker Rd 3130 Killdeer Ave SE Fred Meyer #005 CANBY 2500 Santiam Blvd Fred Meyer #651 North Albany Market 1401 SE 1st Ave 621 NE Hickory Rite Aid #5365 Safeway #2604 1235 Waverly Dr SE 1051 SW 1st Ave Safeway #1659 1990 14th Ave SE CLACKAMAS Target #T609 Fred Meyer #063 2255 14th Ave SE 16301 SE 82nd Dr Walgreens #6530 1700 Pacific Blvd SE DALLAS Walmart #5396 Safeway #4404 1330 Goldfish Farm SE 138 W Ellendale Ave Wheeler Dealer 1740 SE Geary St EUGENE Winco Foods Fred Meyer #325 (Santa Clara) 3100 Pacific Blvd SE 60 Division St 0 - 2.0 miles radius 2.01 - 2.8 miles radius Beaverton from redemption center from redemption center Either Zone FLORENCE 9307 SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy Albertsons #505 99 Ranch Cost Plus World Market #6060 Fred Meyer #464 5415 SW Beaverton Hillsdale Hwy 8155 SW Hall Blvd 10108 SW Washington -

Meal Planning Resources Grocery Weekly Deals and Coupons: Websites

Meal Planning Resources Grocery Weekly Deals and Coupons: Websites These sites offer weekly deals, sale foods, coupons. Like them on Facebook, Sign up on Twitter! -PCC http://specials.pccnaturalmarkets.com/app.asp?Relld=5.5.7.2 - Safeway http://weeklyspecials.safeway.com/customer_Frame.Jsp?drpStoreID=1551&show Flash=false -Trader Joe’s http://www.traderJoes.com/fearless-flyer -QFC http://services.qfc.com/StoreLocator/StoreLocatorWeeklyAdSearch.aspx -Grocery Outlet http://www.groceryoutlet.com/Default/LookingforAd.aspx -Ballard Market/Central Market http://townandcountrymarkets.com/specials/ -Albertson’s http://albertsons.mywebgrocer.com/Circular/Seattle-Hwy-99-and- 130th/7DF73471/Weekly/2/1 Coupons These sites are great for grocery promotions and downloadable coupons -Red Plum http://www.shopathome.com -ibotta phone ap -Chinook Book coupon book and app http://chinookbook.net/ -Whole Foods Coupons www.wholefoodsmarket.com/coupons Meal Planning Websites -Epicurious Meal Planning Recipes for Busy Families http://www.epicurious.com/articlesguides/blogs/editor/2013/01/meal-planning-resources-for- busy-families.html - Whole Foods Daily Meal Planner: Menus, recipes & coupons for a week’s worth of low budget meals http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/about-our-products/whole-deal/meal-planner - USDA Healthy Foods shopping list http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/healthieryou/html/shopping_list.html - 100 Days of Real Food (We love this website!) Includes grocery lists, cost break down, recipes and calendar for 5 weeks of meal planning