The Regional Airline Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes

October 2019 Visa Public gfgfghfghdfghdfghdfghfghffgfghfghdfghfg This document is a supplement of the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules. In the event of any conflict between any content in this document, any document referenced herein, any exhibit to this document, or any communications concerning this document, and any content in the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules, the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules shall govern and control. Merchant Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes Visa Merchant Data Standards Manual – Summary of Changes for this Edition This is a global document and should be used by members in all Visa Regions. In this edition, details have been added to the descriptions of the following MCCs in order to facilitate easier merchant designation and classification: • MCC 5541 Service Stations with or without Ancillary Services has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5542 Automated Fuel Dispensers has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5812 Eating Places, Restaurants & 5814 Fast Food Restaurants have been updated to include greater detail in order to facilitate easier segmentation • MCC 5967 Direct Marketing – Inbound Telemarketing Merchants has been updated to include adult content • MCC 6540 Non-Financial Institutions – Stored Value Card Purchase/Load has been updated to clarify that it does not apply to Staged Digital Wallet Operators (SDWO) • MCC 8398 Charitable Social Service Organizations has -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Merchant Category Codes

Merchant Category Codes MasterCard, Visa, and online debit card networks (card types 013-018, 021-027, and 029- 030) use a 4-digit numeric merchant category code (MCC) to identify the type of business conducted by a merchant. Merchant category codes are used when a new merchant account is added to the System. They are also used in warning bulletins, authorizations, chargebacks, settlement, and in certain types of transactions classified as “quasi-cash” transactions by Visa. Merchant category groups (MCGs) are used with the Commercial Market Analysis product and are general categories under which merchant category codes fall. The System recognizes the following seven merchant category groups when generating the Commercial Market Analysis Reports. MasterCard also requires a single-letter transaction category code (TCC) to identify general merchant categories. The transaction category codes follow. Merchant Category Group Description MCG Code Travel 1 Lodging 2 Dining and entertainment 3 Vehicle expenses 4 Office services and merchandise 5 Cash advance 6 Other 7 MasterCard regulations formerly referred to merchant category codes as Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. Transaction category codes (TCC) were formerly called INAS type codes. Transaction Category Code TCC Merchant Category A Automobile/Vehicle Rentals C or Z Cash Disbursement F Restaurant H Hotel/Motel O College/School Expense O Hospital P Payment Service Provider R All Other Merchants/U.S. Post Exchange T Pre-Authorized Mail/Telephone Order U Unique Transaction Quasi-Cash -

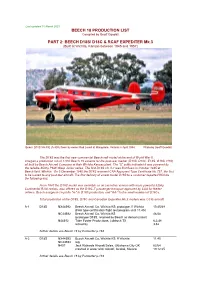

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

The Effect of Airline Pilot Characteristics on Perceptions of Job Safety Risks

THE EFFECT OF AIRLINE PILOT CHARACTERISTICS ON PERCEPTIONS OF JOB SAFETY RISKS By Leon N. Moses and Ian Savage1 A large cross-sectional sample of commercial airline pilots in the United States were asked for their perceptions of job safety hazards. Regression techniques are employed to investigate the relationship between these perceptions and both the length of tenure of pilots, and their specific employer within the industry. The latter is found to have a far more significant impact on risk perception. No evidence was found for a "learning curve" of job risk with respect to experience. Pilots' assessment of inadequacies in training and aircraft maintenance are found to be significantly related to the financial health of their employer. An extensive literature has developed analyzing the effects of hazards in the workplace on labor markets. Viscusi (1979) empirically supports the theoretical hypotheses that "risky" occupations are characterized by both wage premiums to compensate for the risks, and comparatively high turnover rates. The latter observation suggests that some occupational risks only become fully apparent to workers after on-the-job experience. This paper attempts to identify this "learning curve" using a large cross-sectional sample of U.S. commercial airline pilots. The pilots were asked for their risk perceptions on a number of potential job hazards. Regression techniques are employed to investigate the relationship between these perceptions and both the length of tenure of pilots, and their specific employer. In analyzing the inter-employer perceptions of risk, measures of firm size and financial performance are used. Therefore, the paper has a secondary objective of empirically investigating whether the characteristics of firms affect the choices they make in providing for workplace safety, in as far as it is perceived by their employees. -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Americaan Samoa Air Service Marketing Study-Phase Two Report

American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase Two Report August 5, 2014 i American Samoa Air Transport Marketing Study Phase Two Report, August 5, 2014 Contents Recommendations ............................................................................................. i Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 8 Background for Recommendations .................................................................. 8 Task 5 and Task 6: Approaches to Expanding Air Services and Recommended Strategies to Provide Air Transport Services Capacity Needs ................... 19 1. Honolulu and the Mainland ...................................................................................... 20 2. Hawaiian Airlines and Competitors in the US Airline Industry ............................... 22 3. Apia, Manu'a and Savai’i.......................................................................................... 40 4. Neighboring Pacific Islands beyond Samoa ............................................................. 45 5. New Zealand and Australia ...................................................................................... 49 6. Changes in Federal Laws or Regulations ................................................................. 51 7. American Samoa Airports ........................................................................................ 56 8. Immigration -

Signatory Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Carriers

Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Signatory Carriers As of May 1, 2019 Carriers that are highlighted in yellow hold expired Visa Waiver Program Agreements and therefore are no longer authorized to transport VWP eligible passengers to the United States pursuant to the Visa Waiver Program Agreement Paragraph 14. When encountered, please remind them of the need to re-apply. # 21st Century Fox America, Inc. (04/07/2015) 245 Pilot Services Company, Inc. (01/14/2015) 258131 Aviation LLC (09/18/2013) 26 North Aviation Inc. 4770RR, LLC (12/06/2016) 51 CL Corp. (06/23/2017) 51 LJ Corporation (02/01/2016) 620, Inc. 650534 Alberta, Inc. d/b/a Latitude Air Ambulance (01/09/2017) 711 CODY, Inc. (02/09/2018) A A OK Jets A&M Global Solutions, Inc. (09/03/2014) A.J. Walter Aviation, Inc. (01/17/2014) A.R. Aviation, Corp. (12/30/2015) Abbott Laboratories Inc. (09/26/2012) ABC Aerolineas, S.A. de C.V. (d/b/a Interjet) (08/24/2011) Abelag Aviation NV d/b/a Luxaviation Belgium (02/27/2019) ABS Jets A.S. (05/07/2018) ACASS Canada Ltd. (02/27/2019) Accent Airways LLC (01/12/2015) Ace Aviation Services Corporation (08/24/2011) Ace Flight Center Inc. (07/30/2012) ACE Flight Operations a/k/a ACE Group (09/20/2015) Ace Flight Support ACG Air Cargo Germany GmbH (03/28/2011) ACG Logistics LLC (02/25/2019) ACL ACM Air Charter Luftfahrtgesellschaft GmbH (02/22/2018) ACM Aviation, Inc. (09/16/2011) ACP Jet Charter, Inc. (09/12/2013) Acromas Shipping Ltd. -

MCC Description

MCC Description 0742 VETERINARY SERVICES 0743 WINE PRODUCERS 0744 CHAMPAGNE PRODUCERS 0763 AGRICULTURAL COOPERATIVES 0780 HORTICULTURAL AND LANDSCAPING SERVICES 1520 GENERAL CONTRACTORS‐RESIDENTIAL AND COMMERCIAL 1711 AIR CONDITIONING, HEATING, AND PLUMBING CONTRACTORS 1731 ELECTRICAL CONTRACTORS 1740 INSULATION, MASONRY, PLASTERING, STONEWORK, AND TILE SETTING CONTRACTORS 1750 CARPENTRY CONTRACTORS 1761 ROOFING AND SIDING, SHEET METAL WORK CONTRACTORS 1771 CONCRETE WORK CONTRACTORS 1799 CONTRACTORS, SPECIAL TRADE CONTRACTORS‐NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED 2741 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLISHING AND PRINTING 2791 TYPESETTING, PLATE MAKING, AND RELATED SERVICES 2842 SANITATION, POLISHING, AND SPECIALTY CLEANING PREPARATIONS 3000 UNITED AIRLINES 3001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 3002 PAN AMERICAN 3003 EUROFLY 3004 DRAGON AIRLINES 3005 BRITISH AIRWAYS 3006 JAPAN AIR LINES 3007 AIR FRANCE 3008 LUFTHANSA GERMAN AIRLINES 3009 AIR CANADA 3010 ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES (KLM AIRLINES) 3011 AEROFLOT 3012 QANTAS 3013 ALITALIA 3014 SAUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES 3015 SWISS INTERNATIONAL AIR LINES 3016 SCANDINAVIAN AIRLINE SYSTEM (SAS) 3017 SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS 3018 VARIG 3019 GERMANWINGS 3020 AIR INDIA 3021 AIR ALGERIE 3022 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 3023 MEXICANA 3024 PAKISTAN INTERNATIONAL MCC Description 3025 AIR NEW ZEALAND LTD. INTERNATIONAL 3026 EMIRATES AIRLINES 3027 UNION DE TRANSPORTS AERIENS (UTA/INTERAIR) 3028 AIR MALTA 3029 SN BRUSSELS AIRLINES 3030 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 3031 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 3032 EL AL 3033 ANSETT AIRLINES 3034 ETIHADAIR 3035 TAP AIR PORTUGAL (TAP) 3036 VIACAO AEREA