M Innesota's F Orgotten F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

Snakeheadsnepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN a Biologicalmyanmar Synopsis Vietnam

Mongolia North Korea Afghan- China South Japan istan Korea Iran SnakeheadsNepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN A BiologicalMyanmar Synopsis Vietnam and Risk Assessment Philippines Thailand Malaysia INDIAN OCEAN Indonesia Indonesia U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 SNAKEHEADS (Pisces, Channidae)— A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment By Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director Use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Copyrighted material reprinted with permission. 2004 For additional information write to: Walter R. Courtenay, Jr. Florida Integrated Science Center U.S. Geological Survey 7920 N.W. 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 For additional copies please contact: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, Colorado 80225-0286 Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae)—A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment / by Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams p. cm. — (U.S. Geological Survey circular ; 1251) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN.0-607-93720 (alk. paper) 1. Snakeheads — Pisces, Channidae— Invasive Species 2. Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment. Title. II. Series. QL653.N8D64 2004 597.8’09768’89—dc22 CONTENTS Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Literature Review and Background Information . 4 Taxonomy and Synonymy . -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus Elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications Summer 2020 Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River Dakota S. Radford Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Radford, Dakota S., "Aging Techniques & Population Dynamics of Blue Suckers (Cycleptus elongatus) in the Lower Wabash River" (2020). Masters Theses. 4806. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4806 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AGING TECHNIQUES & POPULATION DYNAMICS OF BLUE SUCKERS (CYCLEPTUS ELONGATUS) IN THE LOWER WABASH RIVER By Dakota S. Radford B.S. Environmental Biology Eastern Illinois University A thesis prepared for the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences Eastern Illinois University May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Thesis abstract .................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iv List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v -

Chapter 101 Minnesota Statutes 1941

MINNESOTA STATUTES 1941 101.01 DIVISION OF GAME AND FISH; FISH 846 CHAPTER 101 DIVISION OF GAME AND FISH; FISH Sec. Sec. 101.01 Manner of taking flsh 101.21 Sale of flsh caught In certain counties; o).her 101.02 Manner of taking minnows for bait flsh not bought or sold at any time 101.03 Open season for black bass and yellow bass 101.22 Prohibited methods and equipments 101.04 Open season for trout, except lake trout; 101.23 Polluting streams hours for taking 101.24 Fish screens; removal 101.05 Fishing in trout streams 101.25 Dark houses or fish houses, when used; 101.06 Open season for lake trout licenses 101.07 Open season for pike, pickerel, and muskel- 101.26 Open season for whiteflsh, tullibees, and her lunge ring 101.08 Closed season for sturgeon, hackleback, 101.27 Open season for frogs spoonbill, or paddleflsh. 101.28 Turtles and tortoises 101.09 Open season for crappies 101.29 Fishways; construction; fishing near flshways 101.10 Fishing in boundary waters forbidden 101.11 Open season for fishing in boundary waters 101.30 Fish may be taken and sold from certain lakes 101.12 Open season for sunflsh, rock bass, and other 10.1.31 Regulations by director / varieties 101.32 Restriction 101.13 Open season for sunflsh in Goodhue county 101.34 Sections 101.30 to 101.32 supplementary 101.14 Open season for carp, dogfish, redhorse, 101.35 Disposition of dead flsh sheepshead, catfish, suckers, eelpout, garfish, 101.36 Open season for fishing in Lake of the Woods bullheads, whiteflsh, and buffaloflsh 101.37 Open season for suckers and other rough flsh 101.153 Propagation of game flsh in Lake of the Woods 101.16 When and where artificial lights may be used 101.38 Fishing from towed boats prohibited in spearing certain fish 101.39 Taking of fish in natural spawning beds 101.18 Placing carp in waters prohibited prohibited 101.19 Fishing in Minneapolis 101.40 Fish screens; permits 101.20 Limit of catch 101.01 MANNER OF TAKING FISH. -

Rough Fish”: Paradigm Shift in the Conservation of Native Fishes Andrew L

PERSPECTIVE Goodbye to “Rough Fish”: Paradigm Shift in the Conservation of Native Fishes Andrew L. Rypel | University of California, Davis, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, 1 Shields Ave, Davis, CA 95616 | University of California, Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences, Davis, CA. E-mail: [email protected] Parsa Saffarinia | University of California, Davis, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, Davis, CA Caryn C. Vaughn | University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma Biological Survey and Department of Biology, Norman, OK Larry Nesper | University of Wisconsin–Madison, Department of Anthropology, Madison, WI Katherine O’Reilly | University of Notre Dame, Department of Biological Sciences, Notre Dame, IN Christine A. Parisek | University of California, Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences, Davis, CA | University of California, Davis, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, Davis, CA | The Nature Conservancy, Science Communications, Boise, ID Peter B. Moyle | University of California, Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences, Davis, CA Nann A. Fangue | University of California, Davis, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, Davis, CA Miranda Bell- Tilcock | University of California, Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences, Davis, CA David Ayers | University of California, Davis, Center for Watershed Sciences, Davis, CA | University of California, Davis, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, Davis, CA Solomon R. David | Nicholls State University, Department of Biological Sciences, Thibodaux, LA While sometimes difficult to admit, perspectives of European and white males have overwhelmingly dominated fisheries science and management in the USA. This dynamic is exemplified by bias against “rough fish”— a pejorative ascribing low- to- zero value for countless native fishes. One product of this bias is that biologists have ironically worked against conservation of diverse fishes for over a century, and these problems persist today. -

Commercial Fishing in SOUTH DAKOTA by Todd St

PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF Commercial Fishing IN SOUTH DAKOTA By todd St. Sauver, GFP Fisheries program specialist If you have ever watched reality shows like Deadliest Catch, Swamp Pawn, Bottom Feeders or Alaska: Battle on the Bay, you are familiar with a few of the many types of commercial fishing practiced around the world. But did you know we have commercial fishing in South Dakota? What is commercial fishing? Put simply, it is catching fish or other aquatic animals to sell for profit. Commercial fishing operations can be small, with one person running a few hoop nets for catfish, or large, with massive trawlers and factory ships on the oceans. In the early 1800s, native game fish species were mainly valued as food sources and were commonly harvested by commercial fishermen. By the mid-1800s, these populations began to deplete, so additional sources of fish were considered. In an 1874 report by the newly-formed United States Fish Commission, Professor Spencer F. Baird suggested that the European carp (now called common carp) could solve the problem. Two years later, he again urged the Commission to consider introducing carp to the U.S. because of its ability to reproduce rapidly, grow fast, and live in waters native fish could not survive in. In 1877, the Commission made what may be the greatest fish management mistake in U.S. history. They imported 345 carp from Europe to ponds in Baltimore, Maryland. It was not long until the progeny produced by these fish were stocked into eastern lakes and rivers. Within four years, commercial fishermen were catching carp in Lake Erie and in the Illinois, Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. -

Marine Fishes of the Azores: an Annotated Checklist and Bibliography

MARINE FISHES OF THE AZORES: AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. RICARDO SERRÃO SANTOS, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS SANTOS, RICARDO SERRÃO, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS 1997. Marine fishes of the Azores: An annotated checklist and bibliography. Arquipélago. Life and Marine Sciences Supplement 1: xxiii + 242pp. Ponta Delgada. ISSN 0873-4704. ISBN 972-9340-92-7. A list of the marine fishes of the Azores is presented. The list is based on a review of the literature combined with an examination of selected specimens available from collections of Azorean fishes deposited in museums, including the collection of fish at the Department of Oceanography and Fisheries of the University of the Azores (Horta). Personal information collected over several years is also incorporated. The geographic area considered is the Economic Exclusive Zone of the Azores. The list is organised in Classes, Orders and Families according to Nelson (1994). The scientific names are, for the most part, those used in Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean (FNAM) (Whitehead et al. 1989), and they are organised in alphabetical order within the families. Clofnam numbers (see Hureau & Monod 1979) are included for reference. Information is given if the species is not cited for the Azores in FNAM. Whenever available, vernacular names are presented, both in Portuguese (Azorean names) and in English. Synonyms, misspellings and misidentifications found in the literature in reference to the occurrence of species in the Azores are also quoted. The 460 species listed, belong to 142 families; 12 species are cited for the first time for the Azores. -

Impact of Recreational Fisheries Management on Fish Biodiversity in Gravel Pit Lakes with Contrasts to Unmanaged Lakes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/419994; this version posted September 18, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Impact of recreational fisheries management on fish biodiversity in gravel pit lakes 2 with contrasts to unmanaged lakes 3 S. Matern1, M. Emmrich2, T. Klefoth2, C. Wolter1, N. Wegener3 and R. Arlinghaus1,4 4 1Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater 5 Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587 Berlin, Germany 6 2State Sport Fisher Association of Lower Saxony, Brüsseler Strasse 4, 30539 7 Hannover, Germany 8 3Institute of Environmental Planning, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Herrenhäuser 9 Strasse 2, 30419 Hannover, Germany 10 4Division for Integrative Fisheries Management, Albrecht Daniel Thaer-Institute of 11 Agriculture and Horticulture, Faculty of Life Science, Humbolt-Universität zu Berlin, 12 Philippstrasse 13, Haus 7, 10155 Berlin, Germany 13 14 Correspondence 15 S. Matern, Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, Leibniz-Institute of 16 Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587 Berlin, 17 Germany 18 Email: [email protected] 19 20 Abstract 21 Gravel pit lakes constitute novel ecosystems that can be colonized by fishes through 22 natural or anthropogenic pathways. Many of these man-made lakes are used by 23 recreational anglers and experience regular fish stocking. Recreationally unmanaged 24 gravel pits may also be affected by fish introductions, e.g., through illegal fish 25 releases, thereby contributing to the formation of site-specific communities. Our 26 objective was to compare the fish biodiversity in gravel pit lakes with and without the 27 recent influence of recreational fisheries management. -

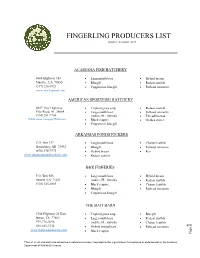

1 Fingerling Producers List

FINGERLING PRODUCERS LIST Updated: November, 2018 ACADIANA FISH HATCHERY 3664 Highway 343 Largemouth bass Hybrid bream Maurice, LA 70555 Bluegill Redear sunfish (337) 230-0123 Coppernose bluegill Fathead minnows www.stockapond.com AMERICAN SPORTFISH HATCHERY 8007 Troy Highway Triploid grass carp Redear sunfish Pike Road, AL 36064 Largemouth bass Fathead minnows (334) 281-7703 (native, FL, hybrid) Threadfin shad www.americansportfish.com Black crappie Golden shiner Coppernose bluegill ARKANSAS PONDSTOCKERS P.O. Box 357 Largemouth bass Channel catfish Harrisburg, AR 72432 Bluegill Fathead minnows (870) 578-9773 Hybrid bream Koi www.arkansaspondstockers.com Redear sunfish B&R FISHERIES P.O. Box 656 Largemouth bass Hybrid bream Swartz, LA 71281 (native, FL, hybrid) Redear sunfish (318) 345-2885 Black crappie Channel catfish Bluegill Fathead minnows Coppernose bluegill THE BAIT BARN 2704 Highway 21 East Triploid grass carp Bluegill Bryan, TX 77803 Largemouth bass Redear sunfish 979-778-3056 (native, FL, hybrid) Channel catfish 800-845-3534 Hybrid striped bass Fathead minnows 1 www.baitbarnfisheries.com Black crappie Page *This list is not intended to be exhaustive or definitive nor does it represent either a guarantee of competence or endorsement by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries FINGERLING PRODUCERS LIST (CONTINUED) DUNN’S FISH FARM P.O. Box 85 Triploid grass carp Hybrid bream Fittstown, OK 74842 Largemouth bass Redear sunfish (800) 433-2950 (native, FL, hybrid) Channel catfish www.dunnsfishfarm.com Black crappie Fathead minnows Coppernose bluegill Koi HOPPER-STEPHENS HATCHERIES 989 Johnson Rd. Triploid grass carp Bream Lonoke, AR 72086 Largemouth bass Catfish (501) 676-2435 Crappie Fathead minnows J.M. -

Long-Term Changes in Population Statistics of Freshwater Drum (Aplodinotus Grunniens) in Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin, Using Otolit

LONG-TERM CHANGES IN POPULATION STATISTICS OF FRESHWATER DRUM ( APLODINOTUS GRUNNIENS ) IN LAKE WINNEBAGO, WISCONSIN, USING OTOLITH GROWTH CHRONOLOGIES AND BOMB RADIOCARBON AGE VALIDATION by Shannon L. Davis-Foust A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences At The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2012 LONG-TERM CHANGES IN POPULATION STATISTICS OF FRESHWATER DRUM ( APLODINOTUS GRUNNIENS ) IN LAKE WINNEBAGO, WISCONSIN, USING OTOLITH GROWTH CHRONOLOGIES AND BOMB RADIOCARBON AGE VALIDATION by Shannon L. Davis-Foust A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2012 Major Professor Dr. Rebecca Klaper Date Graduate School Approval Date ii ABSTRACT LONG-TERM CHANGES IN POPULATION STATISTICS OF FRESHWATER DRUM ( APLODINOTUS GRUNNIENS ) IN LAKE WINNEBAGO, WISCONSIN, USING OTOLITH GROWTH CHRONOLOGIES AND BOMB RADIOCARBON AGE VALIDATION by Shannon Davis-Foust The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2012 Under the Supervision of Dr. Rebecca Klaper Estimating fish population statistics such as mortality and survival requires the use of fish age data, so it is important that age determinations are accurate. Scales have traditionally, and erroneously, been used to determine age in freshwater drum (Aplodinotus grunniens ) in the majority of past studies. I used bomb radiocarbon dating to validate that sagittal otoliths of drum are the only accurate structure (versus spines or scales) for age determinations. Drum grow slower and live longer than previously recognized by scale reading. Drum otoliths can be used not only to determine age, but also to estimate body length. -

Sustainable Exploitation of Small Pelagic Fish Stocks Challenged by Environmental and Ecosystem Changes: a Review

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 76(2): 385–462, 2005 SUSTAINABLE EXPLOITATION OF SMALL PELAGIC FISH STOCKS CHALLENGED BY ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECOSYSTEM CHANGES: A REVIEW Pierre Fréon, Philippe Cury, Lynne Shannon, and Claude Roy ABSTRACT Small pelagic fish contribute up to 50% of the total landing of marine species. They are most abundant in upwelling areas and contribute to food security. Exploit- ed stocks of these species are prone to large interannual and interdecadal variation of abundance as well as to collapse. We discuss why small pelagic fish and fisheries are so “special” with regard to their biology, ecology, and behavior. Two adjectives can sum up the characteristics of pelagic species: variability and instability. Analy- ses of the relationships between small pelagic fish and their physical environment at different time-scales illustrate the complexity of the interplay between exploita- tion and environmental impacts. How small pelagic fish species are positioned and related within the trophic web suggests that these species play a central role in the functioning and dynamics of upwelling ecosystems. Finally, we discuss the sustain- able exploitation of small pelagic fisheries through appropriate management, focus- ing on the resilience to exploitation, a comparison of different management options and regulatory mechanisms. We recommend that statistical, socio-economical, and political merits of a proposed two-level (short- and long-term) management strategy be undertaken. Despite constant progress in understanding the complex processes involved in the variability of pelagic stock abundance, especially at short and medium time scales, our ability to predict abundance and catches is limited, which in turn limits our ca- pacity to properly manage the fisheries and ensure sustainable exploitation.