Julian Hawthorne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorne's Concept of the Creative Process Thesis

48 BSI 78 HAWTHORNE'S CONCEPT OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Retta F. Holland, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HAWTHORNEIS DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER 1 II. PREPARATION FOR CREATIVITY: PRELIMINARY STEPS AND EXTRINSIC CONDITIONS 21 III. CREATIVITY: CONDITIONS OF THE MIND 40 IV. HAWTHORNE ON THE NATURE OF ART AND ARTISTS 67 V. CONCLUSION 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii CHAPTER I HAWTHORNE'S DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER Early in his life Nathaniel Hawthorne decided that he would become a writer. In a letter to his mother when he was seventeen years old, he weighed the possibilities of entering other professions against his inclinations and concluded by asking her what she thought of his becoming a writer. He demonstrated an awareness of some of the disappointments a writer must face by stating that authors are always "poor devils." This realistic attitude was to help him endure the obscurity and lack of reward during the early years of his career. As in many of his letters, he concluded this letter to his mother with a literary reference to describe how he felt about making a decision that would determine how he was to spend his life.1 It was an important decision for him to make, but consciously or unintentionally, he had been pre- paring for such a decision for several years. The build-up to his writing was reading. Although there were no writers on either side of Hawthorne's family, there was a strong appreciation for literature. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

Scholars Portal PDF Export

Localism, landscape, and the ambiguities of place: German- speaking central Europe, 1860-1930 Author(s) Blackbourn, David ; Retallack, James N. Imprint Toronto [Ont.] : University of Toronto Press, c2007 Extent 1 electronic text (viii, 278 p.) Topic DD Subject(s) Nationalism -- Germany; Landscape -- Symbolic aspects -- Germany; National characteristics, German; Home -- History. -- Germany Language English ISBN 9781442684522, 9780802093189 Permalink http://books.scholarsportal.info/viewdoc.html?id=560292 Pages 85 to 106 3 ‘Native Son’: Julian Hawthorne’s Saxon Studies james retallack Fated to stand in the shadow of his gifted father Nathaniel Hawthorne, Julian Hawthorne (1846–1934) might be forgiven for attempting to ‘go native’ when fortune took him to Dresden, capital city of the Kingdom of Saxony. Near the end of an undistinguished period of professional training that began in 1869 and dragged on until 1874, Hawthorne wrote a misanthropic tome entitled Saxon Studies.1 First published seri- ally in the Contemporary Review, the book weighed in at 452 pages when it appeared in 1876. It may well have contributed to Hawthorne’s Brit- ish and American publishers going bankrupt a few weeks later: the only copies that exist today are those sent out for review purposes. Hawthorne claimed that he set out to write an objective, candid appraisal of Saxon society. But if this was a ‘warts and all’ study, the face of Saxony quickly turned into caricature. Soon one saw nothing but warts. Saxon Studies fits into no literary or scholarly genre: it is part autobiography, part travelogue, part social anthropology avant la lettre, and part Heimat romance (stood on its head). -

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop —>

MOTHER MARY ALPHONSA —> ROSE HAWTHORNE LATHROP —> MRS. GEORGE PARSONS LATHROP —> ROSE HAWTHORNE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Rose Hawthorne HDT WHAT? INDEX ROSE HAWTHORNE MOTHER MARY ALPHONSA 1851 May 20, Tuesday: At the “little Red House” in Lenox, Massachusetts, Rose Hawthorne was born to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne. At least subsequent to this period, it seems likely that Nathaniel and Sophia no longer had sexual intercourse, as Nathaniel has been characterized by one of his contemporaries as deficient “in the power or the will to show his love. He is the most undemonstrative person I ever knew, without any exception. It is quite impossible for me to imagine his bestowing the slightest caress upon Mrs. Hawthorne.” Sophia once commented about her husband that he “hates to be touched more than anyone I ever knew.” Presumably the Hawthornes gave up sexual intercourse for purposes of contraception, or perhaps because they found solitary or mutual masturbation to be more congenial, or perhaps, in Nathaniel’s case, because he preferred to have sex with prostitutes, a social practice of the times which Hawthorne referred to as “his illegitimate embraces,” rather than go to the trouble of arranging “blissful interviews” with his wife.1 Hawthorne was bothered by the presence of children, and after the birth of Rose would speak bitterly of the parent’s “duty to sacrifice all the green margin of our lives to these children” towards which he never felt the slightest “natural partiality”: [T]hey have to prove their claim to all the affection they get; and I believe I could love other people’s children better than mine, if I felt they deserved it more. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there sp’e missing pagSb, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6 " X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8822869 The criticism of American literature: The powers and limits of an institutional practice Kayes, Jamie R. Barlowe, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Kayes, Jamie R. Barlowe. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In ail cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

The Ulysses Sumner Milburn Hawthorne Collection Mss. Coll. #3

The Ulysses Sumner Milburn Hawthorne Collection Mss. Coll. #3 Scope & Content The papers in this collection of the American author, Nathaniel Hawthorne, were given to the St. Lawrence University by Dr. and Mrs. Ulysses Milburn (Theological School 1891) in 1949. The literary rights to this collection have not been dedicated to the public. The collection, in its entirety, includes not only first editions of all Hawthorne's work, letters, and manuscripts, but also criticism and interpretations of Hawthorne. Included in the collection are 39 letters written by Hawthorne, dating between 1837 and 1863. In addition there are a number of letters written by members of the Hawthorne family and a few by persons associated with the family. The collection includes manuscripts by Hawthorne, members of his family and historical documents. Most numerous among these are the documents related to Hawthorne's business and financial affairs. Also included are prints, photographs, and pamphlets relating to Hawthorne's literary career. The scrapbook compiled by Dr. Ulysses S. Milburn, includes letters, newspaper clippings, speeches, and articles regarding the history of this collection and its donation to the library. In addition to the scrapbook is the original card catalogue made by Ulysses S. Milburn, which enumerates and describes in loving detail the contents of the entire collection, which contain more than twelve hundred items about the life and work of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Additional items include photographs, Milburn correspondence, clippings and magazine articles about Hawthorne. Biographical Information Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts on July 4, 1804. He was educated at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, and it was here that he began his literary career. -

Louisa May Alcott 1 Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott 1 Louisa May Alcott Louisa Alcott Louisa May Alcott at about age 25 Born November 29, 1832 Germantown, Pennsylvania, United States Died March 6, 1888 (aged 55) Boston, Massachusetts, United States Pen name A. M. Barnard Occupation Novelist Nationality American Period Civil War Genres Prose, Poetry Subjects Young Adult stories Notable work(s) Little Women Signature Louisa May Alcott (November 29, 1832 – March 6, 1888) was an American novelist best known as author of the novel Little Women and its sequels Little Men and Jo's Boys. Raised by her transcendentalist parents, Abigail May and Amos Bronson Alcott in New England, she grew up among many of the well-known intellectuals of the day such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau. Nevertheless, her family suffered severe financial difficulties and Alcott worked to help support the family from an early age. She began to receive critical success for her writing in the 1860s. Early in her career, she sometimes used the pen name A. M. Barnard. Published in 1868, Little Women is set in the Alcott family home, Orchard House, in Concord, Massachusetts and is loosely based on Alcott's childhood experiences with her three sisters. The novel was very well received and is still a popular children's novel today. Alcott was an abolitionist and a feminist. She died in Boston. Childhood and early work Alcott was born on November 29, 1832, in Germantown, which is now part of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on her father's 33rd birthday. She was the daughter of transcendentalist and educator Amos Bronson Alcott and social worker Abby May and the second of four daughters: Anna Bronson Alcott was the eldest; Elizabeth Sewall Alcott and Abigail May Alcott were the two youngest. -

•Œrappaccini's Daughterâ•Š

"Rappaccini's Daughter" - Sources and Names BURTON R. POLLIN RAPPACCINI'S DAUGHTER has always been viewed as one of Hawthorne's strangest and most provocative tales. I should like to consider a few of the possible sources which serve chiefly to under- score the theme of the transformation or re-creation of human life, these being Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Godwin's St. Leon, and Milton's Paradise Lost. Related to the supernatural motif of the story is the meaning in Italian of the names of four major characters. That Hawthorne could not have failed to know Frankenstein has been assumed by R. P. Adams for "The Birthmark." 1Mary Shelley's first work was a celebrated, perhaps even notorious, novel during the period of Hawthorne's early development, and it continued to be popular throughout the century. There were to be at least nine reprints in English of this work of 1818, two of them published in the United States.2 The third edition of 1831, with a long new pre- face by the author, constituted the ninth of the popular "Standard Novels" of Colburne and Bentley.3 Hawthorne probably saw the 1833 Philadelphia reprint by the well-known firm of Carey and Lea, to which he had addressed a request in 1832 concerning an article for the Souvenir, one of its publications.4 Frankenstein is a distinguished specimen of the Gothic tale, a genre which was promi- nent in Hawthorne's reading.5 It has left its traces in The Scarlet 1 R. P. Adams in Tulane Studies, VIII (1958), 115-151, "Hawthorne: The Old Manse" - specifically, p. -

Hawthorne Family Papers, [Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf358002w4 No online items Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Processed by The Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1996 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Literature --American Literature Guide to the Hawthorne Family BANC MSS 72/236 z 1 Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Collection number: BANC MSS 72/236 z The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: The Bancroft Library staff Date Completed: ca. 1972 Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1996 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Hawthorne Family Papers, Date (inclusive): [ca. 1834-1932] Collection Number: BANC MSS 72/236 z Creator: Hawthorne family Extent: Number of containers: 2 cartons, 6 boxes, 4 volumes and 1 oversize folder. Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Abstract: Primarily papers of Julian Hawthorne (correspondence, MSS of his writings and his poetry, journals and notebooks, scrapbooks, clippings, etc.), with a few papers also of his first wife, Minnie (Amelung) Hawthorne, and his second, Edith (Garrigues) Hawthorne. -

Discord in Concord

National Politics and Literary Neighbors DISCORD IN CONCORD Claudia Durst Johnson In addition to works mentioned herein, the influence of Hawthorne on Louisa May Alcott is discernible in the following collections of her work: Louisa May Alcott: Selected Fiction, ed. Daniel Shealy, Madeleine B. Stern, and Joel Myerson (Boston: Little, Brown, 1990); Freaks ofGenius: Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott, ed. Daniel Shealy (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1991); and Alternative Alcott, ed. Elaine Showalter (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1988). n the ~iny New England village of Concord, Massachusetts, at .the height of the I American Civil War, two of the century's fiction writers, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott, with their strong-minded artistic families, lived side-by side. In these few years Hawthorne's powers and reputation dwindled and Alcott's star rose. In one of the most turbulent of political and philosophical times, the families, deeply implicated in so many major national issues, attempted to come to terms with their contradictory politics and clashing t~mperaments during personal and national trial. Despite the unfortunate discord that surfaced between th~ Haw thornes and Alcotts, Louisa May Alcott would find in Hawthorne's work instructive treatments and themes compatible with her own interests and would eventually discover in The Scarlet Letter a means of coping fictionally with her often dysfunc tional family. In many ways, no two souls could be more antithetical, particularly touching the stormy politics of race and gender, than Nathaniel Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott. In marked contrast to Hawthorne, Louisa Alcott ~as a devoted abolitionist, a feminist, and, like her father and mother, an admirer ofJohn Brown. -

The Wayside ______AND/OR COMMON the Wayside "Home of Authors"______LOCATION

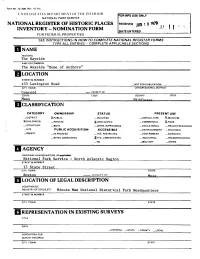

Form No 10-306 I Rev 10-74) UNITLDSTAThS DbPARTMbNT OHHMNItRlOR [FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED JUJJ 1 9 1979 INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS__________ | NAME HISTORIC The Wayside _____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON The Wayside "Home of Authors"______________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 455 Lexington Road _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Concord — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mass M-iH^looo-u- Q CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _OISTRICT XPUBLIC _ OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ?_MUSEUM X-BUILOING(S) _ PRIVATE XUNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .gYES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _!NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS National Park Service - North Atlantic Region STREET* NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE BOStOn ———— VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION Mace COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Minute Man National Historical Park Headquarters STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY TOWN i DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _ EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE .XGDOD RUINS JCALTERED _ FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Wayside, located on the north side of Route 2A, also known as "Battle Road," is part of Minute Man National Historical Park. The Wayside and its grounds extend just over four and a half acres and include the house, the barn, a well, a monument commemorating the centenary of Hawthorne's birth, and the remains of a slave's quarters. -

Hawthorne Family Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf487003nz No online items Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, ca. 1800-1926 Processed by Kate Mustain; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 1999 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Hawthorne Family Special Collections M0981 1 Papers, ca. 1800-1926 Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, ca. 1800-1926 Collection number: M0981 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Kate Mustain Date Completed: 1999 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 1999 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Hawthorne Family Papers, Date (inclusive): ca. 1800-1926 Collection number: Special Collections M0981 Creator: Extent: 2 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Restrictions None. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the repository. Literary rights reside with the creators of the documents or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Public Services Librarian of the Dept. of Special Collections. Provenance Purchased, 1998. Preferred Citation: [Identification of item] Hawthorne Family Papers, M0981, Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Sophia A. Hawthorne [1809 - 1871]: Sophia Amelia Peabody was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on September 21, 1809 to Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and Nathaniel Peabody.