Institute of Commonwealth Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Gowon, Babangida and Abacha Regimes

University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES by SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULTY OF HUMAN SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA January 2001 University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. My deepest gratitude to: Mr. J.T. Bekker for his guidance; Dr. Funmi Olonisakin for her advice, Estrellita Weyers for her numerous searches for sources; and last but not least, my wife Estia-Marié, for her constant motivation, support and patience. This dissertation is dedicated to the children of Africa, including my firstborn, Marco Hoogenraad-Vermaak. ii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S “General Abacha wasn’t the first of his kind, nor will he be last, until someone can answer the question of why Africa allows such men to emerge again and again and again”. BBC News 1998. Passing of a dictator leads to new hope. 1 Jul 98. iii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S SUMMARY THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES By SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK LEADER: Mr. J.T. BEKKER DEPARTMENT: POLITICAL SCIENCE DEGREE FOR WHICH DISSERTATION IS MAGISTER ARTIUM PRESENTED: POLITICAL SCIENCE) The recent election victory of gen. -

Introduction 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South

Notes Introduction 1. Kwame Nkrumah, Towards Colonial Freedom: Africa in the Struggle against World Imperialism, London: Heinemann, 1962. Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Republic of Ghana, 1957–1966. 2. J.M. Roberts, History of the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 425. For further details see Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 31–32. 3. Douglas Farah, “Al Qaeda Cash Tied to Diamond Trade,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2001. 4. Ibid. 5. http://www.africapolicy.org/african-initiatives/aafall.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 6. G. Feldman, “U.S.-African Trade Profile.” Also available online at: http:// www.agoa.gov/Resources/TRDPROFL.01.pdf. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 7. Ibid. 8. Salih Booker, “Africa: Thinking Regionally, Update.” Also available online at: htt://www.africapolicy.org/docs98/reg9803.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 9. For full details on Nigeria’s contributions toward eradication of the white minority rule in Southern Africa and the eradication of apartheid system in South Africa see, Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1966–1999, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003, pp. 79–93. 10. See Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of Zimbabwe: A Study of Foreign Policy Decision Making of an Emerging Nation. Stockholm, Sweden: Bethany Books, 1992, p. 141. 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South Africa 1. “Mr. Prime Minister: A Selection of Speeches Made by the Right Honorable, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa,” Prime Minister of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Lagos: National Press Limited, 1964, p. -

Commonwealth Secretary-General

-S7P' COMMONWEALTH SECRETARY-GENERAL C •,-•;• H. E. Chief Emeka Anyaoku, C.O.N. 16 February 2000 As you might recall, the United Nations and the Commonwealth Secretariat have worked in close D-operation to advance the status of wqmen worldwide. !n 1995, the Commonwealth P!an of Action on Gender and Development (1995-2000) was presented at the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing as a special Commonwealth contribution to the UN Process. We would similarly like to have our recently endorsed Update to the Commonwealth Plan of Action on Gender and Development (2000-2005) presented and spoken to as a Commonwealth contribution to the Special Session of the UN Assembly on the Beijing Platform for Action set for 5-9 June 2000. To this end, the Commonwealth Ministers Responsible for Women sent a special message to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in South Africa in November 1999, asking for approval of its presentation as the Commonwealth's contribution to the UN General Assembly. This was soundly endorsed at CHOGM. My successor as Secretary-General, the Rt. Hon. Don McKinnon will take up post in April. We would like to ensure that we put all procedures into place so that this Update can be presented by him as a Commonwealth contribution to the UN process in June. My staff from the Secretariat will be attending the Preparatory meetings of the Commission for Status of Women and the PrepCom for the Special Session, seeking through your Division for the Advancement of Women, the best means of achieving this. -

National Integration: a Panacea to Insecurity in Nigeria

IJAH 4(2), S/NO 14, APRIL, 2015 15 Vol. 4(2), S/No 14, April, 2015: 15-27 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i2.2 National Integration: A Panacea to Insecurity in Nigeria Adebile, Oluwaseyi Paul Department of History and International Studies, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Phone: +2348037934052 Email: [email protected] Abstract Nigeria is currently confronted with myriads of challenges which is rapidly stagnating the development and progress of her core productive and sensitive sectors. One of the most piercing problems is that of insecurity; in fact, this problematic question has gone beyond disorganizing the domestic environment, it has succeeded in labelling Nigeria repulsively in the international community. However, till present, government efforts toward this challenge has not recorded substantial outcomes; it is within the premises of this condition that this paper considers a more propitiatory means of achieving sustainable national security in national integration. While the paper is conscious of the preceding efforts toward integration in the country, it still beholds untapped resources in it for sustainable security in Nigeria. Hence, the paper strongly advocates a New Crusade on National Integration (NCNI) which will immensely guarantee unity, peaceful co-existence and security in Nigeria. Key words: National Insecurity, National Integration, Peaceful co-existence, Nigeria Introduction Nigeria is a heterogeneous entity composed with a large mass of people from varied cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious affiliations. This attribute have been an Copyright © IAARR 2014: www.afrrevjo.net/ijah Indexed African Journals Online (AJOL) www.ajol.info IJAH 4(2), S/NO 14, APRIL, 2015 16 inextricable appendage to the country, owing to it complex colonial and historic nexus. -

Beyond GDP Conference Proceedings

Beyond GDP Measuring progress, true wealth, and the well-being of nations 19-20 November 2007 Conference Proceedings Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*) : 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://ec.europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg : Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2009 ISBN 978-92-79-09531-3 DOI 10.2779/54600 © European Communities, 2009 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium P RINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER THAT HAS BEEN AWARDED THE EU ECO-LABEL FOR GRAPHIC PAPER (HTTP://EC.EUROPA.EU/ECOLABEL) Conference Proceedings Beyond GDP Measuring progress, true wealth, and the well-being of nations 19-20 November 2007 European Parliament, Brussels organised by European Commission, European Parliament, Club of Rome, WWF and OECD www.beyond-gdp.eu TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 7 Summary notes from the Beyond GDP conference Highlights from the presentations and the discussion 10 CONFERENCE Conference Programme 19 Opening Speech: The challenges of modern societies José Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission 24 Session 1: Measuring progress, true wealth and well-being 27 Joaquín Almunia, Member of the European Commission, Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs 28 Rui Baleiras, Secretary of State for Regional Development, Portugal, and EU Presidency 31 Bruno S. -

UNITED NATIONS REFORMS in This Issue: a Colloquium at NIIA

niianews Newsletter of the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs Volume 1 No. 3 July - September, 2005 UNITED NATIONS REFORMS In this issue: A Colloquium at NIIA Security, Poverty, Infectious Diseases, - The UN Reforms: A Colloquium (HIV/AIDS), Environmental at NIIA Degradation, Conflict between and within states; Nuclear, Radiological, - Presentations at the Chemical and Biological Weapons, Terrorism, Transnational Organized Colloquium Crime, Use of Force, Peace - Reform of the Security Council Enforcement, Peace-Keeping, Post- Conflict Peace-Building and Protection - Why Nigeria deserves a of Civilians. Permanent Seat in the UN In addition, the Report has a section on how to have a more effective UN for Security Council the twenty-first century. This aspect - Exhibition covers reform proposals on all the Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, GCFR, organs of the UN and its charter. All - Founders' Day President and Commander-in-Chief, members were invited to debate the Federal Republic of Nigeria submission thoroughly so that informed - On-going Book Projects decisions could be made about the Reforms. The UN Reforms Challenges Before the UN he United Nations (UN) has been Colloquium on the United Nations Tand still remains the most important or decades now, there have been AReforms was organized by the platform for nation-states to pursue Fcalls for the reorganization and Institute from the 23rd – 25th June, their foreign policy interests and reform of the UN to make it more 2005. The event, which was meant to objectives. The UN, being a vast global relevant to the needs of its members, sensitize the Nigerian public, organization with functional more effective in facing the many particularly members of the involvement in virtually every challenges confronting it and more open intelligentsia, was sponsored by the important sphere of human endeavour and democratic. -

It Is Common to Interpret African Politics in Tribal Or Ethnic Terms. In

Adewale Yagboyaju-Ethnic POlitics, Political Corruption ETHNIC POLITICS, POLITICAL CORRUPTION AND POVERTY: PERSPECTIVES ON CONTENDING ISSUES AND NIGERIA'S DEMOCRATIZATION PROCESS Dewale Adewale Yagboyaju Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria Introduction It is common to interpret African politics in tribal or ethnic terms. In the case of Nigeria, the dominant political behaviour can be defined, on the one hand, in terms of "incessant pressures on the state and the consequent fragmentation or prebendalizing of state-power" (Joseph, 1991 :5). On the other hand, such practices can also be related to "a certain articulation of the factors of class and ethnicity" (ibid). For a better understanding of the essentials of Nigerian politics and its dynamics, it is necessary to develop a clearer perspective on the relationship between the two social categories mentioned above and their effects on such issues as political corruption and poverty. In order to do the necessary formulation that we pointed out in the foregoing, we need to know a bit about the history of Nigeria's birth. Designed by alien occupiers, through the amalgamation of diverse ethnic nationalities in 1914, Nigeria, as it is, cannot be 131 Ethnic Studies Review Volume 32.1 called a nation-state. Although Nigerians are often encouraged to think of the country before their diverse ethnic origins, this seems to be an unattainable desire. Such a desire, if accomplished, will make Nigeria a unique African nation. However, behind the fa<;:ade of ethnic politics in Nigeria, there are such other vested interests as class and personal considerations. Undoubtedly, all these combine to undermine the autonomy and functionality of the state in Nigeria. -

Phases of Nigeria's Foreign Policy II

Phases of Nigeria’s Foreign Policy II Aguiy-Ironsi (Jan. – July 1966); Yakubu Gowon (1966-1975); Murtala Muhammed/Oluesgun Obasanjo (1975-1979); Muhammadu Buhari (1983-1985); Ibrahim Babangida (1985-1993); Sani Abacha (1993-1998); Abdulsalami Abubakar (1998-1999) 1 • Aguiyi-Ironsi • Major General J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi became Nigeria’s first military Head of the State from the ashes of the post-independence political upheavals. • As General Officer Commanding (GOC) the Nigerian Army, and the highest ranking military officer at the time, Aguiyi-Ironsi was invited to take over government on January 16, 1966 by then Acting President Nwafor Orizu, following the death of Balewa and the inability of the civilian administration to quell the post-coup turmoil. • Aguiyi-Ironsi inherited a country deeply fractured along ethnic and religious lines and he ruled for 194 days, from January 16, 1966 to July 29, 1966, when he was assassinated in a military coup. 2 • In trying to douse the regional tensions that intensified after the fall of the First Republic and build national allegiance, he promulgated the “Unification Decree No. 34”, which abrogated Nigeria’s federal structure in exchange for a unitary arrangement. • Aguiyi-Ironsi promulgated a lot of decrees in his attempt to hold the country together. They included: the Emergency Decree, known as the Constitution Suspension and Amendment Decree No.1, which suspended the 1963 Republican Constitution, except sections of the constitution that dealt with fundamental human rights, freedom of expression and conscience, and the Circulation of Newspaper Decree No.2, which removed the restrictions to press freedom introduced by the former civilian administration. -

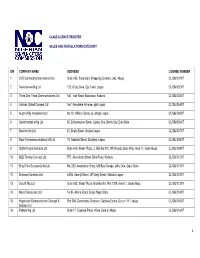

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigeria‟S Foreign Policy Implementation in a Globalised World, 1993-2013 by Raji, Adesina Fatai Matric No. 139084035 August

NIGERIA‟S FOREIGN POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN A GLOBALISED WORLD, 1993-2013 BY RAJI, ADESINA FATAI B.Sc.(Hons.) (B.U.K,Kano), M.A. (LASU, Lagos), M.Sc (UNILAG, Lagos),PGDE(LASU, Lagos) MATRIC NO. 139084035 AUGUST, 2015 NIGERIA‟S FOREIGN POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN A GLOBALISED WORLD, 1993-2013 BY RAJI, ADESINA FATAI B.Sc.(Hons.) (B.U.K,Kano), M.A. (LASU, Lagos), M.Sc (UNILAG, Lagos),PGDE(LASU, Lagos) MATRIC NO. 139084035 BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCINCE, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS. AUGUST, 2015 2 3 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my parents, late Alhaji Akanmu and Alhaja Sikirat Raji; my darling wife, Mrs Sekinat Folake Abdulfattah; and my beloved children: Nusaybah, Sumayyah and Safiyyah who stood solidly by me to make this dream come true. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praise, reverence, adoration and devotion are due to Almighty God alone. He is unique in His Majesty and Authority; He is Sublime in His Wisdom. He alone is the Author and Finisher of all affairs. To Him, I give my undiluted thanks, appreciation and gratitude for His guidance and the gift of good health which He endowed me with throughout the period of this intellectual sojourn. Alhamdulillah! I owe special thanks and appreciation to my beloved parents: Late Alhaji Raji Akanmu and Alhaja Sikirat Raji, for their unwavering spiritual and emotional support and for inspiring my passion to accomplish this intellectual endeavour. This milestone is essentially the manifestation of their painstaking effort to ensure that I am properly educated. -

Nigeria's Elections: Avoiding a Political Crisis

NIGERIA’S ELECTIONS: AVOIDING A POLITICAL CRISIS Africa Report N°123 – 28 March 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. OBASANJO’S ATTEMPTS TO KEEP POWER ....................................................... 2 A. CONTROL OVER PDP NOMINATIONS .....................................................................................2 B. UNDERMINING THE OPPOSITION............................................................................................4 C. THE FEUD WITH ATIKU ABUBAKAR ......................................................................................5 D. RISKS OF BACKFIRE? ............................................................................................................7 III. THE SPREAD OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE............................................................. 9 A. DEMOCRACY WITHOUT DEMOCRATS....................................................................................9 1. God-fatherism............................................................................................................9 2. The increase of political violence ..............................................................................9 B. A THRIVING MARKET FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE................................................................11 C. WORSENING INSURGENCY IN THE NIGER DELTA.................................................................12 -

Nigeria Country Assessment

NIGERIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT COUNTRY INFORMATION AND POLICY UNIT, ASYLUM AND APPEALS POLICY DIRECTORATE IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE VERSION APRIL 2000 I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment has been placed on the Internet (http:www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm). An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE 1 Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees CONTENTS I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 III. ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.3 IV.