Phases of Nigeria's Foreign Policy II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Army Formats in Africa and Post-Colonial Military Coups

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-31 99 COLONIAL ARMY RECRUITMENT PATTERNS AND POST-COLONIAL MILITARY COUPS D’ÉTAT IN AFRICA: THE CASE OF NIGERIA, 1966-1993 ___________________________________________ Dr E. C. Ejiogu, Department of Sociology University of Maryland Abstract Since time immemorial, societies, states and state builders have been challenged and transformed by the need and quest for military manpower.1 European states relied on conscript armies to ‘pacify’ and retain colonies in parts of the non-European world. These facts underscore the meticulous attention paid by the British to the recruitment of their colonial forces in Africa. In the Niger basin for one, conscious efforts were made by individual agents of the British Crown and at official level to ensure that only members of designated groups were recruited into those colonial forces that facilitated the establishment of the Nigerian supra- national state. The end of colonial rule and shifts in military recruitment policies hardly erased the vestiges of colonial recruitment from the Nigerian military. The study on which this article is based and which examines Britain’s policies on military human resource recruitment as state-building initiatives, argued that military coups d’état in Nigeria can be traced back to colonial and post-colonial recruitment patterns for military human resources. Introduction Nigeria, built in the late nineteenth century by British colonial intervention, is Africa’s most populous country.2 Events in Nigeria3 since October 1, 1960, when it acquired political independence from Britain, furthermore attest to the political instability that the country experiences. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Gowon, Babangida and Abacha Regimes

University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES by SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULTY OF HUMAN SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA January 2001 University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. My deepest gratitude to: Mr. J.T. Bekker for his guidance; Dr. Funmi Olonisakin for her advice, Estrellita Weyers for her numerous searches for sources; and last but not least, my wife Estia-Marié, for her constant motivation, support and patience. This dissertation is dedicated to the children of Africa, including my firstborn, Marco Hoogenraad-Vermaak. ii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S “General Abacha wasn’t the first of his kind, nor will he be last, until someone can answer the question of why Africa allows such men to emerge again and again and again”. BBC News 1998. Passing of a dictator leads to new hope. 1 Jul 98. iii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S SUMMARY THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES By SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK LEADER: Mr. J.T. BEKKER DEPARTMENT: POLITICAL SCIENCE DEGREE FOR WHICH DISSERTATION IS MAGISTER ARTIUM PRESENTED: POLITICAL SCIENCE) The recent election victory of gen. -

The Chair of the African Union

Th e Chair of the African Union What prospect for institutionalisation? THE EVOLVING PHENOMENA of the Pan-African organisation to react timeously to OF THE CHAIR continental and international events. Th e Moroccan delegation asserted that when an event occurred on the Th e chair of the Pan-African organisation is one position international scene, member states could fail to react as that can be scrutinised and defi ned with diffi culty. Its they would give priority to their national concerns, or real political and institutional signifi cance can only be would make a diff erent assessment of such continental appraised through a historical analysis because it is an and international events, the reason being that, con- institution that has evolved and acquired its current trary to the United Nations, the OAU did not have any shape and weight through practical engagements. Th e permanent representatives that could be convened at any expansion of the powers of the chairperson is the result time to make a timely decision on a given situation.2 of a process dating back to the era of the Organisation of Th e delegation from Sierra Leone, a former member African Unity (OAU) and continuing under the African of the Monrovia group, considered the hypothesis of Union (AU). the loss of powers of the chairperson3 by alluding to the Indeed, the desirability or otherwise of creating eff ect of the possible political fragility of the continent on a chair position had been debated among members the so-called chair function. since the creation of the Pan-African organisation. -

Middle East - Organization of African Unity - Committee of Ten

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 6 Date 16/05/2006 Time 4:44:14 PM S-0861-0001-06-00001 Expanded Number S-0861 -0001 -06-00001 items-in-Peace-keeping operations - Middle East - Organization of African Unity - Committee of Ten Date Created 30/11/1971 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0861-0001 : Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant: Middle East Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit ME3VIORANDU M DE LA COMMISSION DES DIX DE L'ORGANISATION DE L'UNITE AFHTCAINE Monsieur Anouar El-SADATE President de la Republique arabe d'Egypte et a Madame Golda MEIR Premier Ministre de 1'Etat d'Israel - 2 - Les chefs d'Etat membres de la Commission de 1'O.U.A. 1) M. Moktar Ould DADDAH, President de la Republique islamique de Mauritanie, President en exercice de l'O»U.A. ; 2) Sa Majeste imperials Haile Selassie* ler, Empereur d'Ethiopie ; 3) M. Leopold Sedar SENGHOR, President de la Republique du Senegal ; 4) M. El Hadj Ahmadou AHIDJO, President de la Republique federale du Cameroun ; 5) M. le Lieutenant General Joseph Desire MOBUTU, President de la Republique du Zaire ; 6) M. le General Yakubu GOWON, Chef du Gouvernement militaire federal, Commandant en Chef des Forces armees de la Republique federale du Nigeria ; - 3 - 7) M. William TOLBERT, President de la Republique du Liberia ; 8) M. Jomo KENYATTA, President de la Republique du Kenya, represente par M. Daniel Arap MOI, • Vice-President de la Republique du Kenya ; 9) M. Felix HOUPHOUET-BOIGNY, President de la Republique de C<5te d'lvoire, represente par M. -

AC Vol 41 No 21

www.africa-confidential.com 27 October 2000 Vol 41 No 21 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL NIGERIA I 2 NIGERIA Power and greed Privatisation is keenly favoured by High street havens foreigners and for different reasons The search for Abacha’s stolen money has led to several major by Nigeria’s business class. Western banks and is at last forcing their governments to act President Obasanjo’s sell-off plans are gathering steam but donors Investigators pursuing some US$3 billion of funds stolen by the late General Sani Abacha’s regime complain of delays and worry about between 1993-98 have established that the cash was deposited in more than 30 major banks in state favouritism. Britain, Germany, Switzerland and the United States without any intervention from those countries’ financial regulators. The failure of the regulators to act even after specific banks and NIGERIA II 3 corporate accounts were named in legal proceedings in Britain and congressional hearings in the USA points to a lack of will by Western governments to crack down on corrupt transfers (AC Vol Oduduwa’s children 40 No 23). Quarrels between different departments - with trade and finance officials trying to block any public disclosure of the illicit flows - delayed government action. None of the banks named so President Obasanjo’s efforts to reestablish the nation are at risk far as accepting deposits from Abacha’s family and associates - Australia and New Zealand from violence involving its two Banking Group, Bankers Trust, Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Merrill Lynch, biggest ethnic groups, the Yoruba National Westminster Bank and Paribas - have been formally investigated nor had any disciplinary and the Hausa-Fulani. -

Introduction 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South

Notes Introduction 1. Kwame Nkrumah, Towards Colonial Freedom: Africa in the Struggle against World Imperialism, London: Heinemann, 1962. Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Republic of Ghana, 1957–1966. 2. J.M. Roberts, History of the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 425. For further details see Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 31–32. 3. Douglas Farah, “Al Qaeda Cash Tied to Diamond Trade,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2001. 4. Ibid. 5. http://www.africapolicy.org/african-initiatives/aafall.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 6. G. Feldman, “U.S.-African Trade Profile.” Also available online at: http:// www.agoa.gov/Resources/TRDPROFL.01.pdf. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 7. Ibid. 8. Salih Booker, “Africa: Thinking Regionally, Update.” Also available online at: htt://www.africapolicy.org/docs98/reg9803.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 9. For full details on Nigeria’s contributions toward eradication of the white minority rule in Southern Africa and the eradication of apartheid system in South Africa see, Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1966–1999, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003, pp. 79–93. 10. See Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of Zimbabwe: A Study of Foreign Policy Decision Making of an Emerging Nation. Stockholm, Sweden: Bethany Books, 1992, p. 141. 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South Africa 1. “Mr. Prime Minister: A Selection of Speeches Made by the Right Honorable, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa,” Prime Minister of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Lagos: National Press Limited, 1964, p. -

Commonwealth Secretary-General

-S7P' COMMONWEALTH SECRETARY-GENERAL C •,-•;• H. E. Chief Emeka Anyaoku, C.O.N. 16 February 2000 As you might recall, the United Nations and the Commonwealth Secretariat have worked in close D-operation to advance the status of wqmen worldwide. !n 1995, the Commonwealth P!an of Action on Gender and Development (1995-2000) was presented at the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing as a special Commonwealth contribution to the UN Process. We would similarly like to have our recently endorsed Update to the Commonwealth Plan of Action on Gender and Development (2000-2005) presented and spoken to as a Commonwealth contribution to the Special Session of the UN Assembly on the Beijing Platform for Action set for 5-9 June 2000. To this end, the Commonwealth Ministers Responsible for Women sent a special message to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in South Africa in November 1999, asking for approval of its presentation as the Commonwealth's contribution to the UN General Assembly. This was soundly endorsed at CHOGM. My successor as Secretary-General, the Rt. Hon. Don McKinnon will take up post in April. We would like to ensure that we put all procedures into place so that this Update can be presented by him as a Commonwealth contribution to the UN process in June. My staff from the Secretariat will be attending the Preparatory meetings of the Commission for Status of Women and the PrepCom for the Special Session, seeking through your Division for the Advancement of Women, the best means of achieving this. -

President Clinton's Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign

President Clinton’s Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign Leaders, Representatives, and Dignitaries from January 23, 1993 thru January 19, 20011∗ 1993 Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, January 23, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, January 23, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, January 26, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, January 29, 1993, White House Telephone call with Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel of Turkey, February 1, 1993, White House Meeting with Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel of Germany, February 4, 1993, White House Meeting with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney of Canada, February 5, 1993, White House Meeting with President Turgut Ozal of Turkey, February 8, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus, February 9, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister John Major of the United Kingdom, February 10, 1993, White House Telephone call with Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, February 10, 1993, White House 1∗ Meetings that were only photo or ceremonial events are not included in this list. Meeting with Foreign Minister Michio Watanabe of Japan, February 11, 1993, -

Role of the Military in Democratic Transitions and Succession in Nigeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITY STUDIES Vol 8, No 1, 2016 ISSN: 1309-8063 (Online) ROLE OF THE MILITARY IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS AND SUCCESSION IN NIGERIA E. E. Obioha Walter Sisulu University, South Africa. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] ─Abstract ─ This paper examined the military as an institution and its role in democratic succession in Nigeria. The paper articulated on how various republics in Nigeria failed and what role the military played during these periods. The study relied mainly on secondary data sources, which includes periodicals and other archival documents that provided the required information for the discourse. Data gathered were analyzed through content analysis. Critical and logical analysis of data attested that the military had played the role of distractive force in Nigeria’s democratization process. The military institution presented itself and acted in most occasions as a false custodian of democratic principles by initiating and implementing flawed elections for transition. However, emerging facts further suggest that these democratic principles and arrangements put in place by the military were usually faulty and inadequate for sustainable democratic governance to thrive on. Most general elections organized by the military to transit power have been descriptive of milidemocray, where previous military officers acquire democratic power through stage managed processes. The military institution therefore has functioned as a partisan organisation where various acts of election packaging were learnt and electioneering overtures acquired, despite its instrumental role in sustaining democracy in the country. This paper therefore concludes that the military has been more of a distractive than consolidation force of democratic transitions, and free and fair elections in Nigeria democracy, since her independence. -

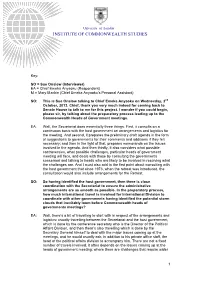

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES Key: SO = Sue Onslow (Interviewer) EA = Chief Emeka Anyaoku (Respondent) M = Mary Mackie (Chief Emeka Anyaoku’s Personal Assistant) SO: This is Sue Onslow talking to Chief Emeka Anyaoku on Wednesday, 2nd October, 2013. Chief, thank you very much indeed for coming back to Senate House to talk to me for this project. I wonder if you could begin, please sir, by talking about the preparatory process leading up to the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings. EA: Well, the Secretariat does essentially three things. First, it consults on a continuous basis with the host government on arrangements and logistics for the meeting. And second, it prepares the preliminary draft agenda in the form of suggestions to governments for their comments and additions if they felt necessary; and then in the light of that, prepares memoranda on the issues involved in the agenda. And then thirdly, it also considers what possible controversies, what possible challenges, particular heads of government meeting will face, and deals with those by consulting the governments concerned and talking to heads who are likely to be involved in resolving what the challenges are. And I must also add to the first point about consulting with the host government that since 1973, when the retreat was introduced, the consultation would also include arrangements for the Retreat. SO: So having identified the host government, then there is close coordination with the Secretariat to ensure the administrative arrangements are as -

President of Guinea Olusegun OBASANDJO, General, President Of

1978 Ahmed SEKOU TOURE (2nd award), President of Guinea 1979 Olusegun OBASANDJO, General, President of Nigeria 1979 Seyni KOUNTCHE, General, President of Niger 1979 E1 Haj Dawda Kairaba JAWARA, President of Gambia 1979 E1 Haj Omar BONGO, President of Gabon NEPAL Order of Ojaswi Rajanya The following list contains the names of recipients of the Order in the period bet~¢een 1951 and 1974. YEAR OF NAME OF THE RECIPIENT AND HIS FUNCTION AT THE AWARD TIME OF AWARD 1951 HIMALAYA Bir Bikram Shah, Prince of Nepal 1951 BASUNDARA Bir Bakram Shah, Prince of Nepal 1954 KANTI Rajya Laxmi Devi Shah, Queen Grand Mother of Nepal 1954 ISHWORI Rajya Laxmi Devi Shah, Queen Grand Mother of Nepal 1960 HIROHITO, Emperor of Japan 1960 NAGAKO, Empress-Consort of Japan 1960 PHILIP, Prince Consort of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Duke of Edinburgh 1960 AKIHITO, Crown Prince of Japan 1960 MICHIKO, Crown Princess Consort of Japan 1961 Mohammad AYUB Khan, Field Marshal, President of Pakistan 1964 RATNA Rajya Laxmi Devi Shah, Queen Mother of Nepal 1964 Dr. Heinrich LUEBKE, President of the Federal Republic of Germany 1967 BERNHARD, Prince Consort of the Netherlands, Prince of Lippe Biesterfeld 1967 BEATRIX, Crown Princess of the Netherlands 1970 HITACHI, Prince of Japan 1970 HANAKO, Princess of Japan 1970 Agha Mohammad YAHYA Khan, President of Pakistan 1972 AISHWARYA Rajya Laxmi Devi Shah, Queen Consort of Nepal 1974 Josip BROZ Tito, Marshal, President of Yugoslavia 1974 Anwar E1 SADAT, Field Marshal, President of Egypt 19 MALI Grand Cross of the National Order The following list contains names of recipients of the Order in the highest class, Presidents of Mall, being Grand Masters of the Order, are recipients ~x ofie~o (during the tenure of their magis- tracy they wear the Collar; afterwards they remain Grand Crosses). -

The Nigerian 2007 Election: a Guide for Journalists and Commentators

Africa Programme Briefing Note AFP BN 07/01 The Nigerian 2007 Election: A Guide for Journalists and Commentators Sola Tayo February 2007 Key Points: • Nigerians will vote in April for a president to replace Olusegun Obasanjo. The election is shaping up to be highly controversial. • Corruption remains a major concern, with allegations reaching as high as the Vice-Presidency. • Whoever wins will face the mounting challenges of the oil-rich but poor and increasingly violent Niger Delta region. Introduction Nigeria’s President, Olusegun Obasanjo, is bucking the trend set by some of his peers across the continent – he is stepping aside after two terms. As the leader of one of Africa’s largest economies, a leading producer and exporter of oil, he must have been greatly tempted to serve another term or two. In fact, he sought to alter the constitution to allow the reigning president to stay beyond two terms but the bid was thrown out by Senate. So who is likely to win favour with Nigeria’s 140 million-strong population? Before their bitter and public falling out last year, Obasanjo’s Vice-President Atiku Abubakar was viewed as his natural successor. Now, with the pair barely on speaking terms and accusing each other of corruption, Abubakar has been forced to campaign under the ticket of another party. Other candidates include the former military heavyweights Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida – the mention of whose name strikes fear into the hearts of many Nigerians – and Muhamadu Buhari. By complete contrast, Obasanjo’s chosen successor is the reclusive and softly spoken Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, the Governor of Katsina state.