Role of the Military in Democratic Transitions and Succession in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Army Formats in Africa and Post-Colonial Military Coups

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-31 99 COLONIAL ARMY RECRUITMENT PATTERNS AND POST-COLONIAL MILITARY COUPS D’ÉTAT IN AFRICA: THE CASE OF NIGERIA, 1966-1993 ___________________________________________ Dr E. C. Ejiogu, Department of Sociology University of Maryland Abstract Since time immemorial, societies, states and state builders have been challenged and transformed by the need and quest for military manpower.1 European states relied on conscript armies to ‘pacify’ and retain colonies in parts of the non-European world. These facts underscore the meticulous attention paid by the British to the recruitment of their colonial forces in Africa. In the Niger basin for one, conscious efforts were made by individual agents of the British Crown and at official level to ensure that only members of designated groups were recruited into those colonial forces that facilitated the establishment of the Nigerian supra- national state. The end of colonial rule and shifts in military recruitment policies hardly erased the vestiges of colonial recruitment from the Nigerian military. The study on which this article is based and which examines Britain’s policies on military human resource recruitment as state-building initiatives, argued that military coups d’état in Nigeria can be traced back to colonial and post-colonial recruitment patterns for military human resources. Introduction Nigeria, built in the late nineteenth century by British colonial intervention, is Africa’s most populous country.2 Events in Nigeria3 since October 1, 1960, when it acquired political independence from Britain, furthermore attest to the political instability that the country experiences. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Gowon, Babangida and Abacha Regimes

University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES by SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULTY OF HUMAN SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA January 2001 University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. My deepest gratitude to: Mr. J.T. Bekker for his guidance; Dr. Funmi Olonisakin for her advice, Estrellita Weyers for her numerous searches for sources; and last but not least, my wife Estia-Marié, for her constant motivation, support and patience. This dissertation is dedicated to the children of Africa, including my firstborn, Marco Hoogenraad-Vermaak. ii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S “General Abacha wasn’t the first of his kind, nor will he be last, until someone can answer the question of why Africa allows such men to emerge again and again and again”. BBC News 1998. Passing of a dictator leads to new hope. 1 Jul 98. iii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S SUMMARY THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES By SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK LEADER: Mr. J.T. BEKKER DEPARTMENT: POLITICAL SCIENCE DEGREE FOR WHICH DISSERTATION IS MAGISTER ARTIUM PRESENTED: POLITICAL SCIENCE) The recent election victory of gen. -

World Bank Document

The Final Draft RAP Report for Agassa Gully Erosion Sites for NEWMAP, Kogi State. Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) FOR AGASSA EROSION SITE, OKENE LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA Public Disclosure Authorized SUBMITTED TO Public Disclosure Authorized KOGI STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KGS-NEWMAP) PLOT 247, TUNDE OGBEHA STREET, GRA, LOKOJA. Public Disclosure Authorized i The Final Draft RAP Report for Agassa Gully Erosion Sites for NEWMAP, Kogi State. RAP Basic Data/Information S/N Subject Data 1 Intervention Site Agassa Gully Erosion sub-project, Okene LGA, Kogi State 2 Need for RAP Resettlement of People Displaced by the Project/Work 3 Nature of Civil Works Stabilization or rehabilitation in and around Erosion Gully site - stone revetment to reclaim and protect road way and reinforcement of exposed soil surface to stop scouring action of flow velocity, extension of culvert structure from the Agassa Road into the gully, chute channel, stilling basin, apron and installation of rip-rap and gabions mattress at some areas. Zone of Impact 5m offset from the gully edge. 4 Benefit(s) of the Intervention Improved erosion management and gully rehabilitation with reduced loss of infrastructure including roads, houses, agricultural land and productivity, reduced siltation in rivers leading to less flooding, and the preservation of the water systems for improved access to domestic water supply. 5 Negative Impact and No. of PAPs A census to identify those that could be potentially affected and eligible for assistance has been carried out. However, Based on inventory, a total of 241 PAPs have been identified. -

The Chair of the African Union

Th e Chair of the African Union What prospect for institutionalisation? THE EVOLVING PHENOMENA of the Pan-African organisation to react timeously to OF THE CHAIR continental and international events. Th e Moroccan delegation asserted that when an event occurred on the Th e chair of the Pan-African organisation is one position international scene, member states could fail to react as that can be scrutinised and defi ned with diffi culty. Its they would give priority to their national concerns, or real political and institutional signifi cance can only be would make a diff erent assessment of such continental appraised through a historical analysis because it is an and international events, the reason being that, con- institution that has evolved and acquired its current trary to the United Nations, the OAU did not have any shape and weight through practical engagements. Th e permanent representatives that could be convened at any expansion of the powers of the chairperson is the result time to make a timely decision on a given situation.2 of a process dating back to the era of the Organisation of Th e delegation from Sierra Leone, a former member African Unity (OAU) and continuing under the African of the Monrovia group, considered the hypothesis of Union (AU). the loss of powers of the chairperson3 by alluding to the Indeed, the desirability or otherwise of creating eff ect of the possible political fragility of the continent on a chair position had been debated among members the so-called chair function. since the creation of the Pan-African organisation. -

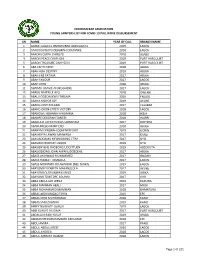

Sn Name Year of Call Branch Name 1 Aamatulazeez Omowunmi Abdulazeez

NIGERIAN BAR ASSOCIATION YOUNG LAWYERS LIST FOR COVID-19 PALLIATIVE DISBURSEMENT SN NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH NAME 1 AAMATULAZEEZ OMOWUNMI ABDULAZEEZ 2019 LAGOS 2 AANUOLUWAPO DEBORAH ODUNAIKE 2018 LAGOS 3 AARON JOSEPH CHIBUZO 2018 ASABA 4 AARON PEACE OSARUCHI 2018 PORT HARCOURT 5 AARON TREASURE ONYIYECHI 2019 PORT HARCOURT 6 ABA FAITH OKEPI 2018 ABUJA 7 ABAH ALIH DESTINY 2019 ABUJA 8 ABAH ENE FATIMA 2017 ABUJA 9 ABAH FAVOUR 2017 LAGOS 10 ABAH JOHN 2018 ABUJA 11 ABAIMU OSAGIE AFOKOGHENE 2017 LAGOS 12 ABAKU BEATRICE AYO 2018 OWERRI 13 ABALU OGECHUKWU THELMA 2018 ENUGU 14 ABANA MOYOR JOY 2019 AKURE 15 ABANG KYIJE ROLAND 2017 CALABAR 16 ABANG OKON-EFRETI VICTORY 2018 LAGOS 17 ABANGWU ADANNA IKWUMMA 2018 IKEJA 18 ABANRE DEBORAH TARIEBI 2018 WARRI 19 ABANULO UCHECHUKWU ABRAHAM 2017 ONITSHA 20 ABANUMEBO MARY EJIO 2018 ABUJA 21 ABANYM DEBORAH OGHENEKEVWE 2019 ILORIN 22 ABASHIYYA LAWAN MAIWADA 2017 KANO 23 ABASIADOAMA MFONOBONG ETIM 2017 UYO 24 ABASIDO MONDAY USORO 2019 UYO 25 ABASIENYENE INIOBONG UDOITTUEN 2019 ABEOKUTA 26 ABASIODIONG JOHN AKPANUDOEDEHE 2017 ABUJA 27 ABASS AKINWALE MUHAMMED 2017 IBADAN 28 ABASS HIKMAT TOMILOLA 2017 LAGOS 29 ABASS MORIAMO OLUWAKEMI (NEE ISIAKA) 2019 LAGOS 30 ABAYOMI ELIZABETH MAKANJUOLA 2017 AKURE 31 ABAYOMI OLORUNWA EUNICE 2019 AWKA 32 ABAYOMI TEMITOPE ADUNNI 2017 OYO 33 ABBA ABDULLAH LEENA 2019 KADUNA 34 ABBA MANMAN ABALI 2017 MUBI 35 ABBA MOHAMMED MAMMAN 2018 DAMATURU 36 ABBAS ABDULRAZAQ TOYIN 2019 EPE 37 ABBAS IDRIS MUHAMMAD 2018 KANO 38 ABBAS SANI ZUBAIRU 2019 KANO 39 ABBEY NGWIATE OGBUJI 2019 LAGOS 40 ABBI -

Portland Paints and Products Nigeria Plc RC76075

You are advised to read and understand the contents of this Rights Circular. If you are in any doubt about the actions to be taken, you should consult your Stockbroker, Accountant, Banker, Solicitor or any other professional adviser for guidance immediately. Investors are advised to note that liability for false or misleading statements or acts made in connection with the Rights Circular is provided in sections 85 and 86 of the Investments and Securities Act No 29, 2007 (the “Act”) For information concerning certain risk factors which should be considered by prospective investors, see Risk Factors on Pages 21 to 24. Portland Paints and Products Nigeria Plc RC76075 Rights Issue of 600,000,000 Ordinary Shares of 50 kobo each at N= 1.70 per Share on the basis of 3 new Ordinary Shares for every 2 Ordinary Shares held as at the close of business on 9 February 2016 The rights being offered in this Rights Circular are tradable on the floor of The Nigerian Stock Exchange for the duration of the Issue Payable in full on Acceptance ACCEPTANCE LIST OPENS: 23 January 2017 ACCEPTANCE LIST CLOSES: 01 March 2017 Issuing House: RC1031358 This Rights Circular and the securities which it offers have been cleared and registered by the Securities & Exchange Commission. The Investments and Securities Act No 29, 2007 provides for civil and criminal liabilities for the issue of a Rights Circular which contains false or misleading information. The clearance and registration of this Rights Circular and the securities which it offers do not relieve the parties of any liability arising under the Act for false and misleading statements or for any omission of a material fact in this Rights Circular. -

Nigerian Gateway Exclusively Electing Leaders at That Level

$1bn arms funds: Reps grill service chiefs, IGP, others today Defence met with the Ministry banditry, Monguno said, “The money, but the money is By: Akorede Folaranmi Nigeria has invited the Monguno (retd.), who said Inspector-General of Police, of Defence on the $1bn special during an interview with the President has done his best by missing. We don't know how, h e H o u s e o f Mohammed Adamu; service security fund released by the Hausa Service of the British approving huge sums of money and nobody knows for now. I Representatives Ad chiefs and other heads of Federal Government in 2017, Broadcasting Corporation on for the purchase of weapons, but believe Mr President will THoc Committee on the paramilitary agencies. part of which was used to pay March 12 that $1bn funds meant the weapons were not bought, investigate where the money Need to Review the Purchase, The security and service for 12 Super Tucano fighter to purchase arms to tackle they are not here. Now, he has went. I can assure you the Use and Control of Arms, chiefs are to explain the jets in the United States. insurgency during the ex-service appointed new service chiefs, President takes issues of this Ammunition and Related procurement and deployment of Reactions had greeted the chiefs' tenure got missing. hopefully, they will devise some nature seriously. Hardware by Military, arms and ammunition in their comments made by the In response to a question on ways. “The fact is that preliminary Paramilitary and Other Law respective agencies. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Nigeria: Obasanjo Backs Lamido/Amaechi Ticket for 2015

Nigeria: Obasanjo Backs Lamido/Amaechi Ticket for 2015 Written by Administrator Thursday, 23 August 2012 09:29 Ahead of political horse trading over who become the presidential and vice presidential candidates of the ruling Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) in 2015, indications emerged last night that former President Olusegun Obasanjo is backing Jigawa State Governor Sule Lamido and his Rivers State counterpart Rotimi Amaechi for the coveted positions respectively. A source close to Obasanjo also confided in LEADERSHIP that the former president is now drumming support for a power shift to the North on the grounds that the region deserves the development. The source, who sought anonymity because of the sensitive nature of the matter, added that Lamido and Amaechi will slug it out with President Goodluck Jonathan and Vice -President Namadi Sambo if Jonathan decides to contest the 2015 poll. He said, "I can authoritatively tell you that Baba (Obasanjo) has thrown his weight behind Lamido/Amaechi ticket for 2015. He is of the opinion that the duo will put in place a dynamic government for positive development. The two governors, you will agree with me, are delivering the dividends of democracy to the people of their states. 1 / 3 Nigeria: Obasanjo Backs Lamido/Amaechi Ticket for 2015 Written by Administrator Thursday, 23 August 2012 09:29 "You will recall that Obasanjo was the mastermind of the late Umaru Yar Adua-Goodluck Jonathan ticket in 2007 when it became clear that the third term agenda had flopped and this was done at the expense of former Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, Mallam Nasir el-Rufai who had been endorsed by the technocrats that served in his second term. -

156 a Study of the Concession Speech by President Goodluck Jonathan Adaobi Ngozi Okoye & Benjamin Ifeanyi Mmadike

A Study of the Concession Speech by President Goodluck Jonathan Adaobi Ngozi Okoye & Benjamin Ifeanyi Mmadike http://dx.doi.org//10.4314/ujah.v17i1.8 Abstract When language is used to communicate to an audience, the listeners are given an insight into the intention of the speaker. This study analyses the concession speech made by President Goodluck Jonathan. It adopts the speech act theory in the classification of the illocutionary acts which are contained in the speech. The simple percentage is used in computing the frequency of the various illocutionary acts. Our findings show a preponderance of the representative speech act and the absence of the directive. Introduction Political discourse has in recent times attracted the interest of researchers hence the role of language in politics and political speeches have been investigated by researchers (Akinwotu, (2013), Waya David (2013) and Hakansson (2012)) . A political speech is seen as a highly guarded form of speech when compared to a commercial speech. Its guarded form is due to its expressive nature and its importance. Speeches are made by politicians as a means of conveying information and opinion to the audience. Usually, these speeches are written in advance by professional speech writers. They are written to be spoken as if not written. In transmitting most of these political speeches via the social networks, it is often the case that highlights of the speeches ,referred to as sound bites, are transmitted. These speeches which are usually communicated through language could be in the form of a campaign speech made before the elections, 156 Husien Inusha: Coherentism in Rorty’s Anti-Foundationalist Epistemology acceptance of nomination speech made after the party’s primaries, concession speech made by a candidate who lost an election or an inaugural speech delivered by the candidate who won an election during his swearing in to the elected office. -

Nigeria: from Goodluck Jonathan to Muhammadu Buhari ______

NNoottee ddee ll’’IIffrrii _______________________ Nigeria: From Goodluck Jonathan to Muhammadu Buhari _______________________ Benjamin Augé December 2015 This study has been realized within the partnership between the French Institute of International Relations (Ifri) and OCP Policy Center The French Institute of International Relations (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. OCP Policy Center is a Moroccan policy-oriented think tank whose mission is to contribute to knowledge sharing and to enrich reflection on key economic and international relations issues, considered as essential to the economic and social development of Morocco, and more broadly to the African continent. For this purpose, the think tank relies on independent research, a network of partners and leading research associates, in the spirit of an open exchange and debate platform. By offering a "Southern perspective" from a middle-income African country, on major international debates and strategic challenges that the developing and emerging countries are facing, OCP Policy Center aims to make a meaningful contribution to four thematic areas: agriculture, environment and food security; economic and social development; commodity economics and finance; and “Global Morocco”, a program dedicated to understanding key strategic regional and global evolutions shaping the future of Morocco. -

Nigerian Newspapers Coverage of the 78 Days Presidential Power

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.11, pp.101-127 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) Nigerian Newspapers Coverage of the 78 Days Presidential Power Vacuum Crisis under President Umaru Yar’adua: Managing or Manipulating the Outcome Ngwu Christian Chimdubem (Ph.D)1 and Ekwe Okwudiri2 1Senior Lecturer and Head, Department of Mass Communication, Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT) Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria. 2Lecturer, Department of Mass Communication, Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa, Edo State Nigeria ABSTRACT: The Nigerian press has always been accused of manipulating political crisis to the gains of their owners or the opposition. This accusation was repeated during the long 78 days (November 23 2009 – February 9 2010) that Nigerian late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua was incapacitated due to ill-health. In fact, observers believed that the kind of media war, power play and intrigue that hailed the period almost cost Nigeria her hard-earned unity and democracy. Eventually, Yar’Adua and his handlers irrefragably lost to ill-health and public opinion. However, the late President’s ‘kitchen cabinet’ believed that he lost ultimately to public opinion manipulated by the press. How true was this? How far can we agree with the kitchen cabinet bearing in mind that this type of accusation came up during the scandals of President Nixon of the United States and the ill health of late President John Attah-Mills of Ghana. Based on these complexities, the researchers embarked on this study to investigate the kind of coverage newspapers in Nigeria gave the power vacuum crisis during Yar’ Adua’s tenure in order to establish whether they (newspapers), indeed, manipulated events during those long 78 days.