Anglo-Norman Money Names in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gold Coins of England, Arranged and Described

THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND. FMOTTIS PIECE. Edward die Coiiiessor. 16 TT^mund, Abp.of Yo Offa . King of Mercia ?.$.&&>. THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND AERANGED AND DESCRIBED BEING A SEQUEL TO MR. HAWKINS' SILVER COINS OF ENGLAND, BY HIS GRANDSON KOBEET LLOYD KENYON See p. 15. Principally from the collection in tlie British Museum, and also from coins and information communicated by J. Evans, Esq., President of the Numismatic. Society, and others. LONDON: BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY MDCCCLXXXIV. : LONDON KV1AN AND <ON, PRINTERS, HART STREET. COVENT r,ARI>E\. 5 rubies, having a cross in the centre, and evidently intended to symbolize the Trinity. The workmanship is pronounced by Mr. Akerman to be doubtless anterior to the 8th century. Three of the coins are blanks, which seems to prove that the whole belonged to a moneyer. Nine are imitations of coins of Licinius, and one of Leo, Emperors of the East, 308 to 324, and 451 to 474, respectively. Five bear the names of French cities, Mettis, Marsallo, Parisius. Thirty- nine are of the seven types described in these pages. The remaining forty-three are of twenty-two different types, and all are in weight and general appearance similar to Merovingian ti-ientes. The average weight is 19*9 grains, and very few individual coins differ much from this. With respect to Abbo, whose name appears on this coin, the Vicomte de Ponton d'Ainecourt, who has paid great attention to the Merovingian series, has shown in the " Annuaire de la Societe Francaise de Numismatique " for 1873, that Abbo was a moneyer at Chalon-sur-Saone, pro- bably under Gontran, King of Burgundy, a.d. -

A Short History of Coins and Currency in Two Parts

P R E F A C E T HI S little b ook is founded on an I nt roduc tory A ddres s w hic h I had the hon ou r of delivering s e om e years ago , as fi rst P r s ident of the I nstitute B s o of anker . I t was , however , alm st rewritten last year as a Lectu r e delivered at the London I nstitution . M r Magnus has done me the honou r of sug ges ti ng that it should be i ncluded as one of the i n Hom e a n d Sei wal L ib rar volu mes the y , which n M r M he is ed iti g for urray,“ 2 3 ' i ” The a1 t i i s ) c w T I t d s w second p f . eal ith the w eights of coins ; the adopted ; the means taken from t i me s ecure a satis n d I f e to factory currency ; a , r gret add , those - also perhaps even more numerous — m b y which Kings and Parliaments have attempted to secu re a temporary and dishonou rable advantage , by debasing the standard and reducing the weight of the coins . I n this respect we may f airly clai m that ou r own Sovereigns and Parl iament are able to show V i PRE F A CE (w ith a few exceptio n s) an u n usually honourable c re ord . I n spite of all that has been written on the ' s u b ec t th e u j , principles on which our c rrency is based are very l ittle understood . -

Auction V Iewing

AN AUCTION OF Ancient Coins and Artefacts World Coins and Tokens Islamic Coins The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Monday 30 September 2013 10:00 Free Online Bidding Service AUCTION www.dnw.co.uk Monday 23 September to Thursday 26 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Strictly by appointment only Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 27, 28 and 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Monday 30 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale VIEWING Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or [email protected] Catalogued by Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley, Jim Brown, Tim Wilkes and Nigel Mills In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb, Peter Preston-Morley or Jim Brown Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Session 1, 10.00 Ancient Coins from the Collection of Dr Paul Lewis.................................................................3001-3025 Ancient Coins from other properties ........................................................................................3026-3084 Ancient Coins – Lots ..................................................................................................................3085-3108 Artefacts ......................................................................................................................................3109-3124 10-minute intermission prior to Session 2 World Coins and Tokens from the Collection formed by Allan -

Detail of a Silver Denarius from the Museum Collection, Decorated with the Head of Pax (Or Venus), 36–29 BCE

Detail of a silver denarius from the Museum collection, decorated with the head of Pax (or Venus), 36–29 BCE. PM object 29-126-864. 12 EXPEDITION Volume 60 Number 2 Like a Bad Penny Ancient Numismatics in the Modern World by jane sancinito numismatics (pronounced nu-mis-MAT-ics) is the study of coins, paper money, tokens, and medals. More broadly, numismatists (nu-MIS-ma-tists) explore how money is used: to pay for goods and services or to settle debts. Ancient coins and their contexts—including coins found in archaeological excavations—not only provide us with information about a region’s economy, but also about historical changes throughout a period, the beliefs of a society, important leaders, and artistic and fashion trends. EXPEDITION Fall 2018 13 LIKE A BAD PENNY Modern Problems, Ancient Origins Aegina and Athens were among the earliest Greek cities My change is forty-seven cents, a quarter, two dimes, to adopt coinage (ca. 7th century BCE), and both quickly and two pennies, one of them Canadian. Despite the developed imagery that represented them. Aegina, the steaming tea beside me, the product of a successful island city-state, chose a turtle, while on the mainland, exchange with the barista, I’m cranky, because, strictly Athens put the face of its patron deity, Athena, on the front speaking, I’ve been cheated. Not by much of course, (known as the obverse) and her symbols, the owl and the not enough to complain, but I recognize, albeit belat- olive branch, on the back (the reverse). They even started edly, that the Canadian penny isn’t money, not even in using the first three letters of their city’s name,ΑΘΕ , to Canada, where a few years ago they demonetized their signify: this is ours, we made this, and we stand behind it. -

Perth Numismatic Journal

Volume 52 Number 3 August 2020 Perth Numismatic Journal Official publication of the Perth Numismatic Society Inc VICE-PATRON Prof. John Melville-Jones EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: 2019-2020 PRESIDENT Prof. Walter Bloom FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Ben Selentin SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Dick Pot TREASURER Alan Peel ASSISTANT TREASURER Sandy Shailes SECRETARY Prof. Walter Bloom MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Sandra Vowles MINUTES SECRETARY Ray Peel FELLOWSHIP OFFICER Jim Selby EVENTS COORDINATOR Prof. Walter Bloom ORDINARY MEMBERS Jim Hidden Jonathan de Hadleigh Miles Goldingham Tom Kemeny JOURNAL EDITOR John McDonald JOURNAL SUB-EDITOR Mike Beech-Jones OFFICERS AUDITOR Vignesh Raj CATERING Lucie Pot PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICER Tom Kemeny WEBMASTER Prof. Walter Bloom WAnumismatica website Mark Nemtsas, designer & sponsor The Purple Penny www.wanumismatica.org.au Printed by Uniprint First Floor, Commercial Building, Guild Village (Hackett Drive entrance 2), The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia 6009 Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 52 No. 3 August 2020 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE PERTH NUMISMATIC JOURNAL Contributions on any aspect of numismatics are welcomed but will be subject to editing. All rights are held by the author(s), and views expressed in the contributions are not necessarily those of the Society or the Editor. Please address all contributions to the journal, comments and general correspondence to: PERTH NUMISMATIC SOCIETY Inc PO BOX 259, FREMANTLE WA 6959 www.pns.org.au Registered Australia Post, Publ. PP 634775/0045, Cat B WAnumismatica website: www.wanumismatica.org.au Designer & sponsor: Mark Nemtsas, The Purple Penny Perth Numismatic Journal Vol. 52 No. 3 August 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PENNY PART I - FROM OFFA TO EDWARD THE CONFESSOR John Wheatley Introduction The history of the simple English penny is not just a reflection of the social and economic history of England; it is about the metals used to produce those coins (gold, silver, copper and bronze) and about the richness of the designs and craftsmanship. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period. -

CATALOGUE of the SCOTTISH COINS Belonging to the SOCIETY of ANTIQUA- RIES of SCOTLAND, Arranged in Chronological Order :—

APPENDIX. CATALOGUE of the SCOTTISH COINS belonging to the SOCIETY of ANTIQUA- RIES of SCOTLAND, arranged in Chronological Order :— No. King. Value. DKAWER 1. Size. Weight. 1. Alexander I. Penny Silver. King's head, regarding the left, with a sceptre, ALEX- D 1107. ADER. REX. R. A cross double parted anchoree, with four stars of six points in the angles -f- W . ER ON BER: Rare. (Supposed to be the first Scottish coin.) 2. 3. • 1. David I. Penny Silver. 1124. 2. 3. APPENDIX. 9 APPENDIX. No. King. Value. DRAWER I. Size. Weight. 1. Alexander III. Penny Silver. King's head crowned, regarding the right, with a E No. King. Value. DRAWER I. Weight. 1249. sceptre, surmounted by a flew de Us. Inscr. Penny Silver. E William the King's head regarding the right, crown with three ALEXADER DEI GRA; a very youthful face. Lyon. 116*. fours de Us, a sceptre, surmounted with four parts R. Cross anchoree extending through the legend, a in cross, behind the head, a crescent embracing a pel- spur revel of six points in the quarters. SCOTO- let, all inclosed within a dotted circle. Inscr. LE. RVM REX. REI WILAM. Do. Very similar to the last, with the exception of two stars E El. Cross anchoree, crescent with two pellets at the and two spur revels on the reverse. angles, inclosed with a circle of pearls. Inscr. 3. Do. Small variation on the reverse in the number of points E ADAM ON EDENBV. to the stars. 2. Do. LE REI WILLAM, as No. 1, with two crescents 4. -

Treasure Act Annual Report 2018

Treasure Act Annual Report 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 12 of the Treasure Act 1996 March 2021 ii Treasure Act Annual Report 2018 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 12 of the Treasure Act 1996 March 2021 1 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021 Compiled by I Richardson Published by Portable Antiquities and Treasure, Learning and National Partnerships, British Museum 2 Contents Minister’s foreword 5 Introduction 6-7 Statistical highlights from Treasure cases 2018 8-21 Table of Treasure cases 2018 22 3 4 Minister’s Foreword It is a great pleasure to introduce this year’s Treasure Act 1996 Annual Report, which gives an overview of how the Treasure Act operated in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2018. The Treasure Act relies on the time and expertise of many people across the country, including Finds Liaison Officers, funding partners and museum teams, who all deserve huge thanks for their hard work and contributions to the process. Finders and landowners are also at the heart of the Treasure Act and it’s brilliant to see 76 finders and landowners who donated their finds in 2018. I’d like to thank the Treasure Registry at the British Museum, the Amgueddfa Cymru/National Museum of Wales and the Department of Environment and Ulster Museum in Northern Ireland for their continued work to support the delivery of the Treasure Act across the UK. The Treasure Valuation Committee has also provided more expert advice this year, and I welcome their new chair, Roger Bland, who brings his formidable knowledge and expertise to the role. -

Ancient Coins Greek Coins

Ancient coins Greek coins 1 Calabria, Tarentum (272-235 BC), silver didrachm, naked horseman, rev. TARAS, Taras riding a dolphin, holding kantharos and trident, AEI and amphora behind, wt. 6.45gms. (Vlasto 904), extremely fine, mint state £200-300 2 Lucania, Herakleia (433-380 BC), silver diobol, hd. of Athena wearing a crested Athenian helmet ornamented with Skylla, rev. Herakles strangling a lion, wt. 1.28gms. (HN. Italy 1379), choice, extremely fine £100-150 3 Lucania, Poseidonia (475-450 BC), silver stater, ΠΟΣΕ, nude Poseidon advancing r. wielding trident with chlamys draped over both arms, rev. ΠOMES, bull stg. r., wt. 8.10gms. (SNG.ANS 654), toned, very fine £200-300 4 Sicily, Gela (465-450 BC), silver litra, bridled horse advancing r., rev. CΕΛΑ, forepart of a male-headed bull r., wt. 0.76gms. (Jenkins 244ff; SNG. ANS 59), toned, extremely fine £100-200 ANCIENT COINS - GREEK COINS 5 6 5 Sicily, Gela (430-425 BC), tetradrachm, quadriga driven by a bearded charioteer, laurel crown in front of the charioteer, rev. CΕΛΑΣ, forepart of a male-headed bull to r., laurel branch to l., wt. 17.30gms. (Jenkins 397; SNG. Ashmolean 1736, same dies); SNG. Copenhagen 266, same dies), struck from worn dies, compact flan, very fine £500-600 6 Sicily, Syracuse (485-478 BC), tetradrachm, struck under Gelon, quadriga driven by a charioteer with Nike flying above crowning the horses, rev. ΣVRAKOΣION, diad. bust of Artemis-Arethusa, with four dolphins around, wt. 17.22gms. (Boehringer 234), about very fine £500-600 7 Sicily, Syracuse (474-450 BC), hd. -

What Is Money?

What is Money? Why Money At some level, we all know what money is. It's the number attached to our bank accounts and stock portfolios that tells us what we can buy and when we can retire - measured in something like Dollars, Euros, Yen, or Pounds. Well, not quite. Those are currencies, different from money in that they have no "intrinsic value." We'll come back to that. For now we will examine money specifically but many of the considerations for money and currency are the same. In broad academic terms, money (or currency) is something like "a distributed medium that transmits information about value and scarcity over time." It is what gives everything a price, and allows one to price everything in terms of everything else. Historically, money has been gold and silver. To really understand money, though, or why it was historically gold and silver, it is useful to think through the implications of using other things in that role. Let's imagine we're a baker in a world with no money. What immediate problems do we have? Well, we have needs to produce our primary good, bread let's say, but no means to store the value of our labor across time. That is, if we make a loaf of bread, we have to trade it for whatever the person who needs a loaf of bread has to trade. Or, if we need flour, we have to hope that whoever has flour wants some of our day old bread. In short, we are in a bartering system, and each transaction we make carries with it a cost of transaction in that we may not have what our suppliers need, or need what our customers have. -

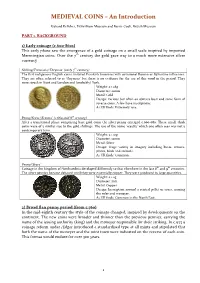

MEDIEVAL COINS – an Introduction

MEDIEVAL COINS – An Introduction Richard Kelleher, Fitzwilliam Museum and Barrie Cook, British Museum PART 1. BACKGROUND 1) Early coinage (c.600-860s) This early phase saw the emergence of a gold coinage on a small scale inspired by imported Merovingian coins. Over the 7 th century the gold gave way to a much more extensive silver currency Shilling/Tremissis/‘Thrymsa’ (early 7 th century) The first indigenous English coins imitated Frankish tremisses with occasional Roman or Byzantine influences. They are often referred to as ‘thrymsas’ but there is no evidence for the use of this word in the period. They were struck in Kent and London and (probably) York. Weight: c.1.28g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Gold Design: various but often an obverse bust and some form of reverse cross. A few have inscriptions. As UK finds: Extremely rare. Penny/Sceat/‘Sceatta’ (c.660-mid 8 th century) After a transitional phase comprising base gold coins the silver penny emerged c.660-680. These small, thick coins were of a similar size to the gold shillings. The use of the name ‘sceatta’ which one often sees was not a contemporary term. Weight: c.1.10g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Silver Design: Huge variety in imagery including busts, crosses, plants, birds and animals. As UK finds: Common. Penny/‘Styca’ Coinage in the kingdom of Northumbria developed differently to that elsewhere in the late 8 th and 9 th centuries. The silver pennies became debased until they were essentially copper. They were produced in large quantities. Weight: c.1.2g Diameter: mm Metal: Copper Design: Inscription around a central pellet or cross, naming the ruler and moneyer. -

A Chartalist View of Numismatics (Fundaments and Necessities of the Discipline 30 Years After the Work by Peter Spufford: Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe)

A CHARTALIST VIEW OF NUMISMATICS (FUNDAMENTS AND NECESSITIES OF THE DISCIPLINE 30 YEARS AFTER THE WORK BY PETER SPUFFORD: MONEY AND ITS USE IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE) XAVIER SANAHUJA-ANGUERA SOCIETAT CATALANA D’ESTUDIS NUMISMÀTICS SpaIN Date of receipt: 13th of July, 2016 Final date of acceptance: 7th of November, 2016 ABSTRACT From a chartalist, non-monetarist starting point, the author analyses basic concepts of numismatics and the history of money, auxiliary disciplines of History, focussing on the medieval epoch and indicating its shortcoming in Catalonia and Spain.1 KEYWORDS Chartalism, Coin, Currency, Monetarism, Money, Numismatics. CapitaLIA VERBA Chartalismus, Moneta, Nummus, Monetarismus, Pecunia, Nummismatica. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, XI (2017): 53-93 / ISSN 1888-3931 / DOI 10.21001/itma.2017.11.02 53 54 XAVIER SANAHUJA-ANGUERA 1. Definitions and prior considerations in numismatics and currency11 1.1 Numismatics, a scientific discipline Numismatics is the auxiliary discipline of history responsible for the study of currency systems, coins and other examples of official tender over history. Secondly, numismatics also studies those objects that have morphological (medals, getons) or functional (tokens, vouchers) similitudes with money. Because of its character as an auxiliary discipline, numismatics needs to be approached with a scientific method. Coins are historical documents that must be studied and defined with scientific criteria before being used for historical interpretation. With this, I refer to a certain currency produced in a specific year, that circulated until another year, which was worth a certain amount, that people paid for with a mark-up that was so and so, etc. These are indisputable data.