The 'Unequalled Artist.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punti D'incontro Nell' Architettura a Malta E in Sicilia

MICHAEL ELUjL PUNTI D'INCONTRO NELL' ARCHITETTURA A MALTA E IN SICILIA L'Architettura e stata definita come "l'espressione piu genuina delle vicende storiche che l'hanno prodotta", e pert an to sara utile cominciare con un brevissimo riferimento alIa storia delle nostre due isole. La civilta a Malta risale al quarto millennio avanti Cristo, e i nostri templi megalitici, COS! complessi nelle loro strutture e COS! misteriosi nella loro grandiosita, testimoniano un popolo di una intelligenza non comune che e approdato qui dalla Sicilia. 1 Al momento dell'abbandono dei maggiori compIessi megalitici nella prima meta del secondo millennio a. C., il popoIo che li aveva costruiti scomparve misteriosamente,2 e con esso scomparve ogni traccia della sua origine e della sua sorte finale. Dopo illungo capitolo della preistoria, la nostra storia documentata si apre con riferimenti casuaIi nelle letterature classiche. La prima menzione di Malta e desunta da una citazione di Nonio e si riferisce ad un episodio della prima guerra punica, cioe a una battaglia navale allargo delle coste meridionali della Sicilia ed a nord-ovest di Malta. Durante la seconda guerra punica, poi, secondo Livio, la flotta cartaginese, avendo perduto le sue basi della Sicilia, faceva di Malta una base avanzata per un eventuale attacco sulle coste siciliane. Scrive ancora Livio che il console romano Tito Sempronio, diretto verso Cartagine, fece una sosta nella nostra isola in cerea dell a flotta cartaginese. In un contesto piu personale, Cicerone nel suo secondo libro In Verres parla di un certo Diodoro, nativo di Malta, che possedeva una cas a in Sicilia ed un'altra a Malta dove aveva amici e famigliari e 10 descrive come un uomo raffinato di cultura greca. -

Malta and Sicily: Miscellaneous Research Projects Edited by Anthony Bonanno

! " # # $% & ' ( ) * *+ , (- . / 0+ 1 ! 2 *3 1 4 ! - * + # " # $ % % & #' ( ) % $ & *! !# + ( ,& - %% . &/ % 0 ( 0 # $ . # . - ( 1 . # . - # # . 2% . % # ( 5 3 # # )# )))' ( % . $ 4 # !5 4 ( *! !#+. ( $ . 1 # 6. 3 ( 3 7- 08 ( 2 . 3 %# !( 5 . +(9 # 3 3 . #.# ( # .:0 ( . !(* ;9<!+ % 4 . ## ( & ! % ! /: # 74 =33 8.0 78.: 7" 8.: # 7 !8 ,30 74>$8( % ! $ #. # ( 0 3 %.3 . $ (## . 3 3% 3 # ( 3 3 7% 83 % 3 # #3 ( 3 # # 3$ 3 (? . 3% ( ! . . ( # # ) #3 ;! 0 @9, #%# # A &((+ ## . .% (% . 0 . # (; ) 3 3 3 # ( . #. 3 3 # #% # ( !"! #$ % ! 43 % ## 3 3 73 8( " #. 3 %! 3 % . . % % ( . 3 # ( 00:> ! 9B;C .< # ## . +D ( % #. % # ! 3 # 3 . 3 ( 2 % # . 3 , 1 # A&( 0 > 3 3 (? ! . 3 2 2 %( )9BE93! ??(F.33 0 # 6(G% . %2 % 3 3 3 # 4 2 % 5 4 ) 5 4 % # 09< #( % 3 %(3# 3 % 4 (E % # 9 -

Management Models of Sustainable Conservation for the Socio-Economic Development of Local Communities

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Construcción y Tecnología Arquitectónicas Management Models of Sustainable Conservation for the Socio-economic Development of Local Communities A case study of the fortifications of Famagusta, Cyprus and other fortified cities in the Eastern Mediterranean Doctoral Thesis Rand Eppich, BArch, MArch, MBA 2019 ii Construcción y Tecnología Arquitectónicas Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Management Models of Sustainable Conservation for the Socio-economic Development of Local Communities A case study of the fortifications of Famagusta, Cyprus and other fortified cities in the Eastern Mediterranean Rand Eppich, Architect, MBA Director: Dr. Professor José Luis García Grinda 2019 iii © Copyright Rand Eppich, 2019 Deposited from Zanzibar, Friday September 13, 2019 Figure 1 – First page, Martinengo Bastion, at the northwest corner Famagusta, Cyprus (Eppich, 2016) iv Tribunal nombrado por el Sr. Rector Magfco. de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día...............de.............................de 20.... Presidente: Juan Monjo Vocal: Susana Mora Vocal: Christian Ost Vocal: Miguel Angel Troitiño Secretario: Fernando Vegas Suplente: Pablo Rodríguez Navarro Suplente: Ona Vileikis Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día..........de........................de 20…. en la E.T.S.I. /Facultad.................................................... Calificación ....................................................... EL PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO -

Spanish Fortifications for the Defense of the Western Mediterranean (Fortificaciones Españolas Para La Defensa Del Mediterraneo Occidental)

SPANISH FORTIFICATIONS FOR THE DEFENSE OF THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN (FORTIFICACIONES ESPAÑOLAS PARA LA DEFENSA DEL MEDITERRANEO OCCIDENTAL) JOSÉ RAMÓN SORALUCE BLOND (1) ABSTRACT .- The Reconquista being finished, the defense and control of the Spanish and Italian coasts forced the Spanish crown to fortify the new systems of bastions of the Western Mediterranean maritime cities. As the largest fortifying company of its time it raised castles, forts and walling with modern systems of military engineering, not only on the Spanish coast but also in the city of Naples, Sicily, the island of Malta and the African port of Oran, Algiers and Tunis. Keywords: Modern fortification. Spanish military architecture. Fortification of North Africa. RESUMEN.- Acabada la Reconquista, el control y la defensa de las costas españolas e italianas obligó a la Corona Española a fortificar con los nuevos sistemas de baluartes numerosas ciudades marítimas del Mediterráneo Occidental, la mayor empresa fortificadora de su tiempo, levantando castillos, fuertes y amurallando con los modernos sistemas de la ingeniería militar, además de la costa española, la ciudad de Nápoles, la isla de Sicilia, la isla de Malta y los puertos africanos de Orán, Argel y Túnez. Palabras clave: Fortificación moderna. Arquitectura militar española. Fortificación del Norte de Africa. 1. – Doctor of Architecture. Professor of the Superior Technical School of Architecture – University of A Coruña. Permanent member of the Galician Royal Academy of fine arts and Academic C. of the Royal Academies -

Dubrovnik in the 14Th and 15Th CENTURIES: a City Between East and West

Dubrovnik IN THE 14th AND 15th CENTURIES: A City Between East and West By BARIŠA KREKIĆ NORMAN UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS Preface By Bariša Krekić h e purpose of this book is to present to the Western Dubrovnik i Levant (1280-1460) (Belgrade, 1956). reader a city whose position and role for a thousand years Dubrovni\ (Raguse) et le Levant au Moyen Age (Paris, Twas in many ways unique in Europe and whose contribution 1961). to the Mediterranean world was of great importance. This Đubrovm\ in the 14th and 15th Centuries: A City Between city, Dubrovnik—“The Jewel of the Adriatic”—has remained Last and West (Norman, 1972). largely unknown to the Western public because of the language barrier. In fact, the vast majority of works on Dubrovnik have been published in Serbo-Croatian. The few publications in other languages are either antiquated or widely scattered. The study of Dubrovnik is made possible by the existence in that city of a large and very valuable archive containing documents from the eleventh century on and also by the publication, in Yugoslavia, of a considerable number of International Standard Book Number: 0-80 61-0 999-8 monographs covering many aspects of Dubrovnik’s life in Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76 -17734 0 various epochs. The research, however, is far from complete, Copyright 19 72 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Publishing Division of and there is still no single, modern history of Dubrovnik. the University. Composed and printed at Norman, Oklahoma, U.S.A., by the University of Oklahoma Press. -

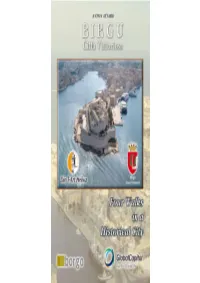

Birgu Promontory Their Knowledge and Experience to Successive Generations of Workers

spread along the coast and some of them could also be seen reaching out into the sea. From the places of worship built in this area, one may conclude that Christians, both of the Byzantine and Roman rites, Hebrews and, even Muslims, although no tangible proof of any mosque exists, all practiced their beliefs in this area. The shores beneath the Castle are the cradle of the technology and craftsmanship of the Island. As early as 1374, in the vicinity of Fort St.Angelo, there was already a well-established dockyard where galleys were built or repaired. In 1501, a bigger dockyard was built. Later, the Order built another one which was considered as the best in the Mediterranean. Eventually, many craftsmen and tradesmen passed on Aerial view of Birgu promontory their knowledge and experience to successive generations of workers. So this city has always been renowned for its craftsmen and tradesmen. Introduction Those who lacked skills earned their living as sailors on the various vessels which berthed alongside Birgu Wharf, later known as Galley Creek, where ships of all kind loaded or unloaded their wares to be sold Being experienced seafarers, the early settlers of these Islands became or bought along the shores of the Marina. This activity reached its climax immediately aware that the coast on the Western side of the promontory on in 1127 when Malta was annexed to the Kingdom of Sicily. which the city of Birgu was later built, offered shelter and security. They The importance which this part of the coast enjoyed was confi rmed realized that at the same time, if they were to be attacked by newcomers, when a castle was built at the end of the promontory. -

ARCHITECTURE and ART in the 14TH CENTURY by Gaetano Bongiovanni

TREASURE MAPS Twenty Itineraries Designed to Help You Explore the Cultural Heritage of Palermo and its Province Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali di Palermo ARCHITECTURE AND ART IN THE 14TH CENTURY by Gaetano Bongiovanni REGIONE SICILIANA Assessorato dei Beni culturali e dell’Identità siciliana PO FESR Sicilia 2007-2013 Linea d’intervento 3.1.1.1. “Investiamo nel vostro futuro” Project TREASURE MAPS Twenty Itineraries Designed to Help You Explore the Cultural Heritage of Palermo and its Province project by: Ignazio Romeo R.U.P.: Claudia Oliva Soprintendente: Maria Elena Volpes Architecture and Art in the 14th Century by: Gaetano Bongiovanni photographs by: Dario Di Vincenzo (fig. 1, 3, 4, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 22, 24, 25, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 45, 48, 49, 56, 57); Diletta Di Simone (fig. 6, 8, 16, 34, 43, 50, 54, 55, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63); Paola Verro (fig. 2, 5, 9, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53); Gero Cordaro, Galleria Regionale della Sicilia di Palazzo Abatellis (fig. 15, 23, 28, 29); Vincenzo Anselmo (fig. 14); Giuseppe Antista (fig. 64); photographic archives of the Soprintendenza of Palermo (fig. 26, 37) we would like to thank the following entities for allowing the use of their cultural possessions: the Fondo Edifici di Culto del Ministe- ro dell’Interno and the Prefettura di Palermo; the Arcidiocesi di Palermo; the Arcidiocesi di Monreale; the Diocesi di Cefalù; the Rettorato dell’Università di Palermo; the Comando della Regione Militare Sud; the Galleria Regionale della Sicilia di Palazzo Abatellis; the Conser- vatorio di Musica di Palermo; the Cooperativa ALI Ambiente Legalità e Intercultura we also thank: Leonardo Artale editorial staff: Ignazio Romeo, Maria Concetta Picciurro graphics and printing: Ediguida s.r.l. -

La Gestione Dell'architettura Civile E Militare a Palermo Tra XVI E XVII Secólo: Gli Ingegneri Del Regno

Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie Vil, /-/.« del Arte, t. 11, 1998, págs. 135-153 La gestione dell'architettura civile e militare a Palermo tra XVI e XVII secólo: gli ingegneri del regno M. SOFÍA DI FEDE * SINTESI ABSTRACT La necessitá di ammodernare e Away the primary concerns for W potenziare le cinture di fortificazioni del century viceroys in Sicily was the centri piú importanti deila Sicilia costituisce modernization and reinforcement of nel Cinquecento una delle principan fortifications around the most important preoccupazioni del viceré; ne conseguirá cities. The direct involvement of the un diretto coinvolgimento dell'autoritá monarchic authority and his engineers monarchica e dei suoi tacnici nell'attivitá was required in the construction process costruttiva e nella riconfigurazione degli and in the reconfiguration of the cities, insediamenti urbani, in particolare della especially in Palermo the capital. The capitale Palermo. Gli ingegneri regí royal engineers involved in these coinvolti in tali vicende, talvolta, erano projects were frequently required to costretti a spostarsi frequentemente, per move around within the Spanish motivi professionali, all'interno deidominii dominions and so often remained in spagnoli, determinando spesso solo brevi Sicily for only brief periods. However in presenze in Sicilia; ma nel caso di the event of a longer stay these permanenze piú durature i tecnia professionals could assume the post of potevano accederé alia carica di «Ingegnere della Regia Corte» which «Ingegnere della Regia Corte», che required residence within the Island. obbligava pero alia residenza nell'lsola. Le The primary duties of this post were capacita richieste erano essenzialmente linked to the reallzation and légate alia realizzazione e alia maintenance of defensivo structure but manutenzione delle strutture difensive, ma also clearly covered the spectrum of any é owio che dovessero coprire l'intero viceroys architectural activity. -

Messina Messina

Messina Messina Così lo scrittore vicentino Guido Piovene descrive Messina nel suo “Viaggio in Italia” del 1957: “Rasa al suolo dal terremoto del 1908, e ricostruita in baracche, Messina è nata come città moderna dopo il 1928. La guerra la distrusse una seconda volta; rinacque ancora, con enorme impulso edilizio ... Messina è città ariosa, spaziosa, come vogliono le precauzioni antisismiche. Palermo è greve, ribollente; Messina è brillante, graziosa e vivace. Nelle sue larghe e lunghe strade i negozi non sono meno ricchi dei palermitani. Vi spiccano nel mio ricordo gli orologiai e i dolcieri. Qui ti vengono incontro, in cornice moderna, i dolci siciliani dai colori vividi, quelli in pasta di mandorle, che fingono frutti e animali, i torroni, le spume alla cioccolata e al limone, chiamate “pinolate”. Una via panoramica circonda Messina in altura. Seguendo il mare verso il Faro, traversate contrade e villaggi che, come dicono i loro nomi, Paradiso, Contemplazione, Pace, sono piccole oasi della borghesia messinese, si mangiano i frutti di mare coltivati nel piccolo lago del Pantano Grande. Si spalanca davanti uno stretto sempre agitato, decorato di spume; il mare siciliano, d’un colore profondo e scuro, quasi in blocchi di blu massicci, su cui il bianco delle onde spicca come in un intarsio; così diverso dal mare napoletano, che invece è diafano, leggero, quasi sospeso, lunare anche di giorno. Su queste acque messinesi si pesca alla fiocina il pescespada, inseguendolo lungo la scia lasciata dalla pinna, su barche dalla chiglia nera a sei rematori”. Messina, capoluogo di provincia della Sicilia nord orientale, conta poco più di 240.000 abitanti, e si protende sullo Stretto omonimo. -

Il Ruolo Geopolitico Degli Ordini Cavallereschi a Malta

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE Sede Amministrativa del Dottorato di Ricerca UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BUCAREST (ACCADEMIA ROMENA – ISTITUTO PER LE SCIENZE POLITICHE E LE RELAZIONI INTERNAZIONALI), CLUJ-NAPOCA-BABE BOLYAI, KOPER/CAPODISTRIA-PRIMORSKA, MESSINA, NAPOLI “FEDERICO II”, PARIS-SORBONNE (PARIS IV – U.F.R. DE GEOGRAPHIE), PARMA, PÉCS (HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES – CENTRE FOR REGIONAL STUDIES), PIEMONTE ORIENTALE “A. AVOGADRO”, SANNIO, SASSARI, TRENTO, UDINE Sedi Convenzionate XX CICLO DEL DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN GEOPOLITICA E GEOECONOMIA (SETTORE SCIENTIFICO-DISCIPLINARE M-GGR/02) IL RUOLO GEOPOLITICO DEGLI ORDINI CAVALLERESCHI A MALTA DOTTORANDO Dott. ALBERTO PANIZZOLI COORDINATORE DEL COLLEGIO DEI DOCENTI Chiar. mo Prof. MARIA PAOLA PAGNINI – UNIV. DI TRIESTE ____________________________________ RELATORE E TUTORE Chiar. mo Prof. MARIA PAOLA PAGNINI – UNIV. DI TRIESTE ____________________________________ ANNO ACCADEMICO 2006-2007 Si ringrazia la prof.ssa Maria Paola Pagnini per l’incoraggiamento e le preziose indicazioni durante la ricerca. Per i consigli, desidero ricordare il prof. Aldo Colleoni, Michael Galea e il dott. Oliver Farrugia Assistent Manager-Ministry for Tourism and Culture- Malta. Ringrazio inoltre: la National Library di Malta e il National Museum of Fine Arts-Heritage Malta, l’Österreichisches Staatsarchiv di Vienna, il Pokrajinski Muzej di Maribor e la Biblioteca Civica “Attilio Hortis” di Trieste. 2 INDICE INTRODUZIONE............................................................................. pag. 5 -

Accademia Internazionale Melitense

ACCADEMIA INTERNAZIONALE MELITENSE Introduzione Storica / Historical Introduction CARLO MARULLO DI CONDOJANNI siciliano, controllò l’Isola, gli arabi spadroneggiarono nell’arcipelago maltese, e, ciò che è certo, nel 973 vi costruirono un castello che rimase come loro fortificazione, finché Ruggero di Normandia non li allontanò nel 1090 dalle Isole Maltesi. Il Castello, secondo alcuni storici, aveva base rotonda ed era in prossimità del distrutto Tempio di Giunone. Impadronitosi dell’Isola, Ruggero il Normanno fortificò a sua volta il manufatto ed assicurò numerosa presenza di soldati a protezione del porto. Bisogna arrivare al dominio degli Angioini tra il 1266 e il 1284 per avere notizia dell’esistenza della Chiesa di Sant’Angelo, Chiesa che sorgeva sul “Castello al mare”, qualche volta citato come “Rocca dell’Isola di Malta” (Castello del Porto, Castello della Marina) . Denominazioni Il manufatto costituito dalla fortificazione arabo-normanna e dalla Chiesa di Sant’Anna deve attendere la metà del secolo XIV per assumere definitivamente il nome di Castel Sant’Angelo. Sull’argomento qualcuno lo deriva dal nome del Conte Angelo De Malfi, Governatore dell’Isola nel 1552; altri si rapportano invece alla concessione del feudo costituito dalle isole maltesi ad Angelo Cazzolis, personaggio del Regno di Napoli. Forse la denominazione di Castel Sant’Angelo è da mettere in correlazione con lo stesso Castel Sant’Angelo di Roma. E’ certo che al tempo della presenza sul promontorio della famiglia de Nava, il “Castello sul Mare” prende il nome di Sant’Angelo. Sempre dal punto di vista storico, a parte le ipotesi esposte in precedenza, il nome di Sant’Angelo appare solo nel luglio 1540, quando in un documento esistente viene usato questo nome a proposito di un Cavalier Claudius Humbliéres che fu ristretto nel carcere di Sant’Angelo. -

Landscape Days

LANDSCAPE DAYS International Syposium The future of the historic urban landscape of Dubrovnik, UNESCO World Heritage new methodologies for urban conservation in the context of development management mr.sc. Maja Nodari Translated into English by Pave Brailo “4 Dubrovnik” draft Dubrovnik, 6th & 7th of November 2014 1 2 INSTEAD OF INTRODUCTION Recent years have seen more and more efforts on the part of UNESCO to per- ceive the world that is constantly becoming complex, which is then reflected on the situation in space, due to the merciless expansion of capital. The space is being changed while we watch it, endangering the protected world heritage. That is why the efforts are aimed at prevention, not on action after degradation. UNESCO’s Advisory Committee, ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) brings out guidelines for HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT – HIA for World Cultural heritage places. The term of landscape, according to the Euro- pean Landscape Convention applies to the entire space and comprises natural, rural, urban and suburban areas, as well as inland waters and the seas. The space is no longer considered partially, but as a whole – including urbanized ar- eas, building complexes under protection with their environment. This applies to the world heritage to which Dubrovnik belongs with its immediate surround- ings and its wide cultivated environment. It is both necessary and urgent to start applying new methods in the protection and management of the natural and cultural heritage (with an accent on the legal framework). However, the Nestor of our Art history, Cvito Fisković, told me long ago that any law is useless, unless heritage is written in the heart! 3 SUMMARY Str.