Contextualizing Palestinian Political Succession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (March 23 – April 6, 2021)

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" )מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (March 23 – April 6, 2021) Overview Coronavirus: In the Gaza Strip the number of active cases spiked significantly this past week, and a lockdown is being considered. In Judea and Samaria there was a significant decrease in coronavirus infection, although hospital occupancy is still high. Palestinians in Judea, Samaria and the Gaza Strip continue to receive the vaccines. A senior figure in the ministry of health in Ramallah blamed Israel for the entrance of the coronavirus variants into the Palestinian Authority (PA) territories. Palestinian foreign minister Riyad al-Maliki accused Israel of exploiting the hardships of countries around the world and of extorting them in return for the promise of coronavirus vaccines. He also claimed that the hardships of the Palestinian people were exacerbated during the coronavirus epidemic because Israel shirked its duty as an "occupying power" to take care of them and because of its refusal to provide them with vaccines. Terrorist attacks: On March 23, 2021 (election day in Israel) a medium-range rocket was fired from the Gaza Strip at Beersheba, the largest city in Israel's south. The rocket landed in an open area. No casualties were reported. It was the attack after two months without rocket fire. In response Israeli Air Force aircraft attacked a number of Hamas terrorist targets in the Gaza Strip. In Judea and Samaria two vehicular ramming attacks targeting IDF soldiers were attempted. -

Democratizing the PLO

PRIO POLICY BRIEF 03 2012 Visiting Address: Hausmanns gate 7 gate Hausmanns Address: Visiting NO Grønland, 9229 PO Box (PRIO) Oslo Institute Research Peace Democratizing the PLO Prospects and Obstacles - 0134 Oslo, Norway Oslo, 0134 Visiting Address: Hausmanns gate 7 gate Hausmanns Address: Visiting NO Grønland, 9229 PO Box War (CSCW) Civil of Study the for Centre While the PLO has been recognized both by the international commu- nity and by Israel as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, the organization remains undemocratic. Its leadership is not elected. The PLO represents the secular resistance groups of the past, - 0134 Oslo, Norway Oslo, 0134 not the political reality of today. In 2011, however, an agreement was reached between the main Palestinian political groups to hold elections for the PLO. It is planned that these elections will include all Palestini- ans, regardless of their location, in accordance with the principle of ful- ISBN: 978 ISBN: www.prio.no ly proportional representation. Recent Arab uprisings for democracy make regional conditions favourable for the holding of such elections. - 82 - 7288 Meanwhile, Western governments fear that the PLO could come to be - 408 dominated by Islamists who do not recognize the State of Israel. In the - 5 (online); (online); past, such considerations have discouraged the PLO from opening up 978 for democratic reforms. However, the fall of President Hosni Mubarak - 82 - in Egypt has acted as a warning to PLO leaders that sustaining an un- 7288 - 409 democratic and secular PLO could hit back with a vengeance. - 2 (print) Dag Tuastad Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) The Legitimacy Crisis tation might be in the context of Palestinian Palestinian people at large. -

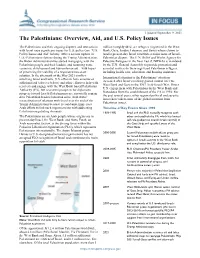

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada

The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada Yoram Schweitzer The decades-long Israeli-Palestinian conflict has seen several rounds of violence and has claimed many casualties on both sides. The second 1 intifada occupies a particularly painful place, especially for the Jewish population, which suffered an unprecedented high casualty toll – dead and injured – in a relatively short period of time. As part of the violence perpetrated by the Palestinians during the second intifada, suicide bombings played a particularly prominent role and served as the primary effective weapon in the hands of the planners. Since the outbreak of the second intifada in late September 2000 until today, there have been a total of 146 suicide attacks, and more than 389 2 suicide attacks have been foiled. Although the relative representation in the total number of hostile activities waged by Palestinian organizations was not high, suicide attacks were without a doubt the most significant component in the death and destruction they sowed. In the decade since September 2000, 516 of the 1178 deaths (43.8 percent) were caused by suicide attacks. In addition to the attacks on Israeli civilians, which also resulted in thousands of physical and emotional casualties, suicide bombings helped the Palestinian organizations instill fear among the Israeli public and create a sense – even if temporary – of danger on the streets, on public transportation, and at places of entertainment. This essay presents a short description and analysis of the rise and fall of suicide terrorism in the decade since the second intifada erupted. It then presents the Israeli and Palestinian perspectives regarding their relative success in attaining their respective goals. -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Jim Zanotti Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 17, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34074 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Summary This report covers current issues in U.S.-Palestinian relations. It also contains an overview of Palestinian society and politics and descriptions of key Palestinian individuals and groups— chiefly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Palestinian Authority (PA), Fatah, Hamas, and the Palestinian refugee population. The “Palestinian question” is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but to many countries and non-state actors in the region and around the world— including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is marked by efforts to establish a Palestinian state through a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; to counter Palestinian terrorist groups; and to establish norms of democracy, accountability, and good governance within the Palestinian Authority (PA). Congress has appropriated assistance to support Palestinian governance and development amid concern for preventing the funds from benefitting Palestinian rejectionists who advocate violence against Israelis. Among the issues in U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is how to deal with the political leadership of Palestinian society, which is divided between the Fatah-led PA in parts of the West Bank and Hamas (a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization) in the Gaza Strip. Following Hamas’s takeover of Gaza in June 2007, the United States and the other members of the international Quartet (the European Union, the United Nations, and Russia) have sought to bolster the West Bank-based PA, led by President Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. -

Steht Später Die Headline

INT ERVIEW Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES A prisoner as a beacon of hope? INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY MARC FRINGS The Fatah politician Marwan Barghouti has been jailed in Israel for the last 15 years. His wife, Fadwa Barghouti, explains how he views UND ABEER ZAGHARI the current state of affairs in Palestine. April 2017 The name of Marwan Barghouti features On 15 April 2002 Marwan Barghouti was prominently in any discussion about again captured by Israel and indicted for i.e. www.kas.de/ramallah change within the Palestinian political complicity in murder and active membership www.kas.de leadership. In the eyes of the Palestinian in a terrorist organization. He was convicted public Barghouti is a national hero enjoy- by an Israeli civil court in December 2002 Follow us on ing strong support. Israel, on the other and sentenced to five times life imprison- hand, considers him a terrorist who ment plus 40 years.1 Israel considers Bar- should remain in prison for the rest of his ghouti a terrorist who represents the life. On the occasion of the 15th anniver- bloody face of the Second Intifada. Within sary of his arrest on 15 April 2002 as well the Palestinian society, however, he can re- as a large-scale hunger strike Palestinian ly on strong and broad support as the prisoners began on 17 April 2017, KAS- public perceives him as a “man of the Ramallah met with Fadwa Barghouti, his street”. Pictures of the imprisoned Barghou- wife and sole means of communication ti, often in Che Guevara iconography, are with the outside world. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ESTHER KLIEMAN ) by and through its Administrator, ) AARON KESNER ) ) and ) ) NACHMAN KLIEMAN ) ) and ) ) RUANNE KLIEMAN ) ) and ) ) DOV KLIEMAN ) ) and ) ) YOSEF KLIEMAN ) ) and ) ) GAVRIEL KLIEMAN ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY (a.k.a. ) “THE PALESTINIAN INTERIM SELF- ) GOVERNMENT AUTHORITY”) ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) THE PALESTINIAN LIBERATION ) ORGANIZATION (a.k.a. “PLO”) ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) FATAH ) c/o The Palestinian Authority and PLO ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) AL AQSA MARTYRS BRIGADE (a.k.a. ) “MARTYRS OF AL AQSA” ) c/o The Palestinian Authority and PLO ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) TANZIM ) c/o The Palestinian Authority and PLO ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) FORCE 17 ) c/o The Palestinian Authority and PLO ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) YASSER ARAFAT ) c/o The Palestinian Authority ) 1320 18th Street, N.W. ) Suite 200 ) Washington, DC 20036 ) ) and ) ) MARWAN BARGHOUTI ) c/o Israel Prison Authority ) Jerusalem, ISRAEL ) 2 ) and ) ) TAMER RASSAM SALIM RIMAWI ) c/o Israel Prison Authority ) Jerusalem, ISRAEL ) ) and ) ) HUSSAM ABDUL-KADER AHMAD ) HALABI a/k/a ABU ARAV ) c/o Israel Prison Authority ) Jerusalem, ISRAEL ) ) and ) ) AHMED HAMAD RUSHDIE ) HADIB a/k/a AHMED BARGHOUTI ) c/o Israel Prison Authority ) Jerusalem, ISRAEL ) ) and ) ) ANNAN AZIZ SALIM HASHASH ) West Bank, ISRAEL ) ) ____________________________________) COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. This action is brought pursuant to federal counterterrorism statutes, Antiterrorism Act of 1991, 18 U.S.C. -

A Decade Since the Outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada: a Strategic the IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland the Rise and Fall

Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade |Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | Shiri Tal-Landman המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 CONteNts Abstracts | 3 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | 7 Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | 27 Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | 39 Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | 49 Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | 63 Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | 71 Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | 85 Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | 101 Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade | 123 Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | 133 Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | 141 Shiri Tal-Landman The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and Strategic enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, ASSESSMENT on Israel’s national security agenda. -

Tensions Rise As Palestinians Jailed in Israel Launch Hunger Strike

Middle East Tensions rise as Palestinians jailed in Israel launch hunger strike By Ruth Eglash April 19 at 2:54 PM RAMALLAH, West Bank — It has been three days since more than 1,000 Palestinian political prisoners detained in Israeli jails declared an openended hunger strike, turning tensions up a notch in the decadesold, intractable conflict. The protest is a peaceful one, say the prisoners, a fight to improve deteriorating living conditions imposed by the Israeli Prison Service. Allowing more family visits, educational options and more public telephones are their central demands. Palestinian Authority literature also mentions torture, unfair trials, detention of children, medical negligence and solitary confinement experienced by prisoners. But Israelis say the strike is not about living standards. Conditions for jailed Palestinians, many of whom have killed Israelis, exceed international standards, they say. It’s about politics, the Israelis insist: a battle for leadership within the Palestinian Authority over who might replace Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas when the time comes. The issue is an emotional one for both sides. To Palestinians, the prisoners are political fighters tried by a foreign entity and held in foreign jails; to Israelis, they are terrorists with Israeli blood on their hands. As the hunger strike goes on, both sides fear an eruption of violence should one of the prisoners die. About 6,500 Palestinian prisoners are jailed in Israel, and more than 800,000 Palestinians have been incarcerated at one time or another over the past 50 years, according to the Palestinian Prisoners Club, a 24yearold support group for Palestinian detainees. -

Palestinian Factions

Order Code RS21235 Updated June 8, 2005 CRS Report for Congress .Received through the CRS Web Palestinian Factions Aaron D. Pina Analyst in Middle East Religious & Cultural Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Palestinian factionalism continues to dominate the political landscape in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The manner in which competing nationalist, socialist, Islamist, and democratic-minded Palestinians vie to control the direction of any future Palestinian state may influence United States objectives in the region. These include ending anti- Israeli violence, supporting Palestinian reforms, and bolstering Palestinian democratization and civil society. Some factions are designated foreign terrorist organizations by the State Department. One of these, Hamas, is building on recent electoral successes and may soon join the Palestinian parliament. This report describes the dominant Palestinian factions, and will be updated as events warrant. See also CRS Issue Brief IB91137, The Middle East Peace Talks. Overview Recent and upcoming Palestinian local, municipal, and legislative elections are drawing the attention of policymakers to Palestinian factions.1 The purpose of this report is to describe dominant Palestinian factions and some of the challenges that factions present. For decades, Palestinian factionalism has dominated the political landscape in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. With Hamas, a dominant faction, faring well in local and municipal elections and poised to gain parliamentary representation, the United States and Israel, in all likelihood, will be faced with a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) in a position of political authority. Also, during the current Palestinian uprising that began in September 2000, violence and terrorism against Israelis has been conducted not only by Hamas, but also factions related to the PLO, and Fatah in particular. -

Is the EU Losing Credibility in Palestine?

> > POLICY BRIEF ISSN: 1989-2667 Nº 50 - JUNE 2010 Is the EU losing credibility in Palestine? Daniela Huber The Israeli attack on the Gaza Flotilla and the resulting diplo- >> matic reverberations have engendered clear international agreement on one subject: that the Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip has to be lifted. The EU’s foreign policy chief, Catherine Ashton, was HIGHLIGHTS quick to condemn the attack and urged Israel to lift the blockade, call- ing it ‘unacceptable’ and ‘counterproductive’. This move would be a • The EU should actively first step to improving the deteriorating living conditions in Gaza. But it must be remembered that the Middle East Quartet contributed support a Palestinian to the current impasse through its political boycott of the elected reconciliation process, Hamas government and, perhaps more crucially, of the National Uni- resulting in elections without ty Government, which would have provided an opportunity for Pales- further delay tinian reconciliation. • The EU has lost credibility The divide in Palestinian society prevails. In 2009, national elections as a normative actor since originally scheduled for January 2010 were postponed to an unknown its political boycott of date. This postponement counted with the EU’s silent support. Now Hamas: it should re-energise President Abbas has also delayed the municipal elections planned for its approach to democracy July 2010. The elections had already been boycotted by Hamas and promotion, focusing on were to take place in the West Bank only. Palestinian civil society capacity building The postponement of the elections comes in the wake of the Flotilla attack with mounting calls for Palestinian unity to bring about an end to the blockade of the Gaza Strip. -

Marwan Barghouti: Partner for Peace Negotiations Or Terrorist?1

July 17, 2017 Marwan Barghouti: Partner for Peace Negotiations or Terrorist?1 Demonstration in Judea and Samaria during the hunger strike of the Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails, led by Marwan Barghouti. Demonstrators waved yellow Fatah flags and held pictures of Marwan Barghouti. The Arabic reads, "The engineer of the intifada and the symbol of national unity" (Arabs48, May 16, 2017). This study examines the milestones in the life of Marwan Barghouti in an effort to reveal and analyze the profound changes that occurred over the years within Fatah and in his positions regarding Israel. One of the issues examined was why Barghouti, who supported the Oslo Accords, was perceived as a peace activist and held talks with a broad spectrum of Israeli public figures, later became a terrorist operative (convicted of the premeditated murder of five people and of directing the second intifada). This study also tries to evaluate the degree of Marwan Barghouti's popularity within Fatah and Palestinian society, and his chances of becoming Mahmoud Abbas' successor. Another issue examined is whether Barghouti, even after having been convicted of terrorist activity during the second intifada, could be a partner in negotiations for peace between Israel and the Palestinians. 1 The full version of this study can be accessed in Hebrew on the ITIC website and is currently be translated into English. 091-17 091-17 2 2 Main Points 1. Marwan Barghouti (Abu Qassam) was born in the village of Kobar (northwest of Ramallah) in 1959. He joined the ranks of Fatah in 1974, at the age of 15.