Unmasking 'King John of Portugal'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Napoleon Series

The Napoleon Series Officers of the Anhalt Duchies who Fought in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1789-1815: Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß, Friedrich Ferdinand, Prince, and then Duke of By Daniel Clarke Friedrich Ferdinand, Duke of Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß was born on June 25, 1769 in Pleß, or Pless, (Pszczyna), Upper Silesia, Prussia. He was the second son of Friedrich Erdmann, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß (1731-1797), a Generalleutnant in the Prussian army, and his wife Louise Ferdinande of Stolberg-Wernigerode. He was therefore the older brother of Heinrich (1778-1847) and Christian Friedrich (1780-1813). In August 1803 Friedrich married Marie Dorothea Henriette Luise, Princess of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg- Beck, but she died that November. He married again in May 1816 to Julia of Brandenburg, a daughter of King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, and they had no children. Friedrich entered Prussian service as a Lieutenant in September 1786 in the 15th Infantry Regiment, von Kunitzky. Just under two years later, in March 1788, he became a Staff Captain in the 28th Infantry Regiment, von Kalckstein, but two months later he was made a Line Captain and company commander in the same regiment. When the French Revolutionary Wars began in 1792, he was promoted to Major on May 6 of that year and transferred to the 10th Fusilier (Light Infantry) Battalion, von Forcade—which changed its title to von Martini later in 1792. For his actions in 1792 he was given the Pour le Mérite in January 1793. With his battalion Friedrich fought with distinction in a host of engagements including at Hochheim on January 6 and Alsheim on March 30, 1793, where he was wounded on both occasions. -

A Welcome to Issue Number 2 of Iron Cross by Lord Ashcroft

COLUMN A welcome to Issue Number 2 of Iron Cross by Lord Ashcroft am delighted to have been asked to write a welcome Germany was an empire of 25 “states”; four kingdoms, six to this the second issue of Iron Cross magazine and to grand duchies, seven principalities and three Hanseatic be able to commend this splendid publication to the free cities. reader as an important historical journal. It provides Most had their own armies, even though some were Ian honest and objective look at German military history extremely small, consisting of just a single infantry from 1914 to 1945 for the first time. regiment. In most cases, these armies were trained, Over the past 33 years, I have built up the world’s organised and equipped after the Prussian model. largest collection of Victoria Crosses, Britain and the Although in wartime, these armies fell under the control Commonwealth’s premier gallantry award for bravery of the Prussian General Staff, the creation and bestowal ■ A selection of German gallantry awards from the First World War: L to R, Prussian Iron Cross 2nd Class, Prussian Knight’s Cross of the Royal House Order in the face of the enemy. As such, I am now the humble of gallantry awards remained a privilege of the territorial of Hohenzollern with Swords, Military Merit Cross 2nd Class of the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Hamburg Hanseatic Cross and Honour Cross of custodian of more than 200 VCs from a total of over lords and sovereigns of the Reich. The reality was that the World War. -

Orders, Medals and Decorations

Orders, Medals and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Lower Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 1 December 2016 at 12.00 noon and 2.30 pm Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 28 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 29 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 30 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 83 Price £15 Enquiries: Paul Wood, David Kirk or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 239 (front); lot 344 (back); lot 35 (inside front); lot 217 (inside back) Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com, www.numisbids.com and www.sixbid.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the under- standing that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connec- tion. -

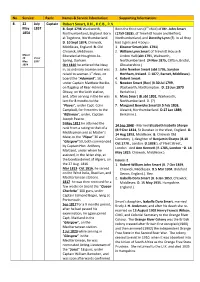

Captain Robert Smart, K.H., K.C.B., R.N. May 1857 B

No. Service: Rank: Names & Service Information: Supporting Information: 8. 22 July Captain Robert Smart, K.H., K.C.B., R.N. May 1857 B. Sept 1796.Warkworth, Born the third son (4th child) of Mr. John Smart 1854 Northumberland, England. Born (1759-1828), of Trewhitt house and Belford, at Togstone, Northumberland. Northumberland, and Dorothy Lynn (?). In all they D. 10 Sept 1874, Chiswick, had 3 girls and 4 boys:- Middlesex, England. B. Old 1. Eleanor Smart(abt. 1791) Chiswick, Middlesex. 2. William Lynn Smart of Trewhitt House & Mason Educated at Houghton-le- Lindon Hall (abt 1791, Wakworth, 29 25 Jul May. 1857 Spring, Durham. Northumberland. 24 Nov 1875, Clifton, Bristol, 1854 Oct 1810 he entered the Navy Gloustershire.) in, as ordinary seaman and was 3. John Newton Smart (abt 1795, Saryton raised to seaman 1st class, on Hortham, Ireland. D.1877, Barnet, Middlesex). board the “Adamant”, 50, 4. Robert Smart. under Captain Matthew Buckle, 5. Newton Smart (Rev) (B.30 Jul 1799, on flagship of Rear-Admiral Wastworth, Northampton. D. 23 Jun 1879 Otway, on the Leith station, Berkshire.). and, after serving in the he was 6. Mary Smart (B.abt 1801, Warkworth, lent for 8 months to the Northumberland. D. (?) “Plover”, under Capt. Colin 7. Margaret Bewicke Smart(B.5 Feb 1803, Campbell, for 9 months to the Alewick, Northumberland. D.27 Jan 1889, “Rifleman”, under, Captain Berkshire.). Joseph Pearce. 9 May 1811 he attained the 14 Sep 1848 - Married Elizabeth Isabella Sharpe rank from a rating to that of a (B.9 Dec 1814, St Dunstan in the West, England. -

British, Russian, Chinese and World Orders, Medals, Decorations and Miniatures

British, Russian, Chinese and World Orders, Medals, Decorations and Miniatures To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2012 at 10.00am and 2.30pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 60 Price £15 Enquiries: James Morton or Paul Wood in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com and www.invaluable.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the understanding that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connection. -

Illastrations

Illastrations 91-III-1 90-VIII-3 90-X-5 90-VIII-4 90-VIII-3 37 INDENTIFICATION REQUEST 91-III-2 From Mark Kraatz, OMSA #4475 Bavarian medal struck in grey metal (non-magnetic), 39mm m diameter OBVERSE: "LUDWIG II KOENIG V.BAYERN" surrounding h~s coinage head, with small letters"NP"in the undercut of the neck. REVERSE "25.8 1845- 13.6.1886" along the upper c~rcumference, In the center isa Bavarian shield w~th letter "N" superimposed and with three leaves sprouting on each s~de of the shield. Below is the signature "Ludwig". IDENTIFICATION REQUEST 91-III-3 From 1. V. Victorov-Orlov, OMSA #2815 A bronze medal, 31.75mm in diameter plus a shght protrusion at the top. with a hole through it for suspension. OBVERSE: a styllzcd shcll, like the symbol of Shell Oil Company. This is surrounded by an Arabic inscr~ption. REVERSE: multiple shells within decorative designs surround a center bearing Arabic inscriptions. 38 BOOK REVIEWS JAil books for rewew should be sent to Charles P. McDowell, JOMSA Book Review Editor;6801 Sue PaigeCt; Springfteld, VA22152. After review books become the property of the OMSA Library.] Aviation Awards of Impertal Germany in World War 1, Volume II, "The Aviation Awards of the Kingdom of Prussia" by Neal W. O’Connor; published in 1990 by The Foundation for Aviation World War I; P.O. Box 212: Princeton, NJ 08542,; 285 pages, dlustrated. Available from the Foundation for $30 (postage and handling included). Those who were pleased with Neal O’Connor’s first volume, The A viation A wards of ttteKingdom of Bavaria,will be delighted with this companionvolume. -

The London Gazette, August 4, 1863. 3809

THE LONDON GAZETTE, AUGUST 4, 1863. 3809 Her Majesty Ihe Queen of the United His Majesty the Emperor of the French, the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Charles Sieur Joseph Alphonse Paul, Baron de Malarct, Augustus Lord Howard de Walden and Sea- Officer of the Legion of Honour, Grand Cross of ford, a Peer of the United Kingdom, Knight the Order of the Guelphs of Hanover, Grand Cross Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the of the Order of Henry the Lion of Brunswick, Bath, Her Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Supernumerary Commander of the Order of Plenipotentiary to His Majesty the King of the Charles III of Spain, &c., His Envoy Extraordi- Belgians; nary and Minister Plenipotentiary to His Majesty His Majesty thg Emperor of Austria, King of the King of the Belgians ; Hungary and Bohemia., the Sieur Charles Baron His Majesty the King of Hanover, the Sieur de^ETugel, Knight of the Imperial and Royal Order Boldo, Baron do Hodcnbcrg, decorated with the of the Iron Crown of the first class, Knight of the fourth class of the Order of the Guelphs of Imperial and Royal Order of Leopold of Austria, Hanover, Commander of the Order of the Nether- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph of Tuscany, land Lion, Minister Resident of His Majesty the Grand Cordon of the Order .of St. Gregory the King of Hanover to Their Majesties the King of Great, Senator Grand Cross of the Constantino the Belgians and the King of the Netherlands ; Order of St. George of Parma, Knight of the Papal His Majesty the King of Italy, the Sieur Albert Order of Christ, Commander of the Royal Order Lupi, Count de Montallo, Grand Cordon of the of Danebrog of Denmark and of the Royal Order Order of St. -

Independant State of Katanga Order of Merit Copy Post-1963 U.So

Independant State of Katanga Order of Merit copy post-1963 U.So Bronze Star to Foreisn Officers Foreign Military in the grade of colonel and below can be awarded the U.S. Bronze Star ~ledal by major Pacific commanders "for direct support of U.So combat operations in Southeast Asia and Korea. The DA has delegated authority to approve such awards to the C-l-C, UoS. Army Pacific, CG, Eighth Army (Korea), Senior Army Command, ~b~CV, and senior Army commander, ~CTHAI. These commanders are instructed to request clearance of State Department officials on the scene to make certain the award is not inconsistant with the overall interests of the U.S. government. Such awards are also supposed to be based on the same criteri~ used for U.S. military earning the bronze star. Army Times April 29, 1970 First Award~ Joint Service Distinguished Service Medal The Army Times announced on June S, last, that General Earle G. Wheeler upon his retirement will receive the first award of another new U.S. medal. Its design has not yet been made public by the Army Institute of Iteraldry that has been working on this award. It is presumed that this mefal will be available for award to those on the Defense Department level and for other joint and unified command service. The Decorations of General-Feldmarschall Helmuth Karl Bernard Graf yon Moltke BY: Edward S. Haynes In his article in the August 1967 Medal Collector conmerning the 1870 Iron Cross, Mr. Dan W. Ragsdale listed General-Feldmarschall van Moltke among the recipients of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross. -

War Medals, Orders and Decorations

War Medals, Orders and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Wednesday 28 November 2007 at 10.00 am, 12.00 noon and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 29 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 1298 (front); Lot 1067 (back); Lot 1293 (inside front cover) and Lot 1310 part (inside back cover). in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. A Buyer’s Premium of 15% is applicable to all lots in this sale. -

Medals, Orders and Decorations Including the Peter Maren Collection

Medals, Orders and Decorations including The Peter Maren Collection To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Tuesday 2 July 2013 at 10.30am and 2.30pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Thursday 27 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 28 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 1 July 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 65 Price £15 Enquiries: Paul Wood or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 123 (front); lot 397 (back); lot 117 (inside front); lot 317 (inside back) in association with Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www mortonandeden.com Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed starting prices. * Illustrated lots are marked with an asterisk. Further images, including photographs of additional items not illustrated in the printed catalogue, can be found online. A Buyer’s Premium of 20% is applicable to all lots in this sale and is subject to VAT at the standard rate (currently 20%). Unless otherwise indicated, lots are offered for sale under the Auctioneer’s Margin Scheme. -

Four Ser~Es Originating in 1906, 1908, 1910 and 1916. Each Series Contained Breast Badges, and All Grades in All Series Are Scarce

four ser~es originating in 1906, 1908, 1910 and 1916. Each series contained breast badges, and all grades in all series are scarce. The ORDER FOR ARTS AND SCIENCES, in Detmold only, was of three classes whose badge design represented a rose in full bloom. Also called "The Rose of Lippc," it was bestowed from 1898 to 1918. Schaumburg-Ltppc’s ORDER FOR ART AND SCIENCE from 1899 included a silver enameled cross to 1914, a gilt enameled cross from 1914 to 1918, and a plain silver cross as the Second Class from 1902 to 1918. MECKLENBURG-SCttWERIN and MECKLENBURG-STRELITZ: The HOUSE ORDER OF TItE WENDISIt CROWN was founded in both states in 1864, but the insignia differed in the motto, "Per Aspera Ad Astra" in Schwerin and "Avito Viret Honore" in Strelitz. There were four classes with several variants but the knight grade, in gold or gilt, was only infrequently augmented with swords. The Strelitz badges of this order are far less common than those of Schwerin. The ORDER OF TttE GRIFFONwas established in Schwerin in 1884 and extended to Strelitz in 1904. The single knight badge could be augmented with a crown as a higher distinction in exceptional cases. NASSAU: The ORDER OF MERIT OF ADOLPHUS OF NASSAU was founded in 1858 and became obsolete in 1866. It had a knight grade in gold and a silver cross in the fourth class. Both were occasionally augmented with swords. The order was revived in Luxembourg about 1890 and there is a challenge in telling those badges from the earlier Nassau series. -

War Medals, Orders and Decorations Including a Fine Collection of Miniatures

War Medals, Orders and Decorations including a fine collection of Miniatures To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Friday 12 December 2008 at 12.00 noon Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Monday 8 December 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 9 December 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 10 December 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Thursday 11 December 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 36 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton or Paul Wood Cover illustrations: Lot 948 (front); Lot 802 (back); ex Lot 949 (inside front cover); ex Lot 925 (inside back cover) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”.