A Yorktown Surrender Flag — Symbolic Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

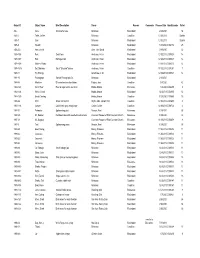

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

The Napoleon Series

The Napoleon Series Officers of the Anhalt Duchies who Fought in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1789-1815: Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß, Friedrich Ferdinand, Prince, and then Duke of By Daniel Clarke Friedrich Ferdinand, Duke of Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß was born on June 25, 1769 in Pleß, or Pless, (Pszczyna), Upper Silesia, Prussia. He was the second son of Friedrich Erdmann, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen-Pleß (1731-1797), a Generalleutnant in the Prussian army, and his wife Louise Ferdinande of Stolberg-Wernigerode. He was therefore the older brother of Heinrich (1778-1847) and Christian Friedrich (1780-1813). In August 1803 Friedrich married Marie Dorothea Henriette Luise, Princess of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg- Beck, but she died that November. He married again in May 1816 to Julia of Brandenburg, a daughter of King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, and they had no children. Friedrich entered Prussian service as a Lieutenant in September 1786 in the 15th Infantry Regiment, von Kunitzky. Just under two years later, in March 1788, he became a Staff Captain in the 28th Infantry Regiment, von Kalckstein, but two months later he was made a Line Captain and company commander in the same regiment. When the French Revolutionary Wars began in 1792, he was promoted to Major on May 6 of that year and transferred to the 10th Fusilier (Light Infantry) Battalion, von Forcade—which changed its title to von Martini later in 1792. For his actions in 1792 he was given the Pour le Mérite in January 1793. With his battalion Friedrich fought with distinction in a host of engagements including at Hochheim on January 6 and Alsheim on March 30, 1793, where he was wounded on both occasions. -

A Welcome to Issue Number 2 of Iron Cross by Lord Ashcroft

COLUMN A welcome to Issue Number 2 of Iron Cross by Lord Ashcroft am delighted to have been asked to write a welcome Germany was an empire of 25 “states”; four kingdoms, six to this the second issue of Iron Cross magazine and to grand duchies, seven principalities and three Hanseatic be able to commend this splendid publication to the free cities. reader as an important historical journal. It provides Most had their own armies, even though some were Ian honest and objective look at German military history extremely small, consisting of just a single infantry from 1914 to 1945 for the first time. regiment. In most cases, these armies were trained, Over the past 33 years, I have built up the world’s organised and equipped after the Prussian model. largest collection of Victoria Crosses, Britain and the Although in wartime, these armies fell under the control Commonwealth’s premier gallantry award for bravery of the Prussian General Staff, the creation and bestowal ■ A selection of German gallantry awards from the First World War: L to R, Prussian Iron Cross 2nd Class, Prussian Knight’s Cross of the Royal House Order in the face of the enemy. As such, I am now the humble of gallantry awards remained a privilege of the territorial of Hohenzollern with Swords, Military Merit Cross 2nd Class of the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Hamburg Hanseatic Cross and Honour Cross of custodian of more than 200 VCs from a total of over lords and sovereigns of the Reich. The reality was that the World War. -

The Federal State of Hesse

Helaba Research REGIONAL FOCUS 7 August 2018 Facts & Figures: The Federal State of Hesse AUTHOR The Federal Republic of Germany is a country with a federal structure that consists of 16 federal Barbara Bahadori states. Hesse, which is situated in the middle of Germany, is one of them and has an area of just phone: +49 69/91 32-24 46 over 21,100 km2 making it a medium-sized federal state. [email protected] EDITOR Hesse in the middle of Germany At 6.2 million, the population of Hesse Dr. Stefan Mitropoulos/ Population in millions, 30 June 2017 makes up 7.5 % of Germany’s total Anna Buschmann population. In addition, a large num- PUBLISHER ber of workers commute into the state. Dr. Gertrud R. Traud As a place of work, Hesse offers in- Chief Economist/ Head of Research Schleswig- teresting fields of activity for all qualifi- Holstein cation levels, for non-German inhabit- Helaba 2.9 m Mecklenburg- West Pomerania ants as well. Hence, the proportion of Landesbank Hamburg 1.6 m Hessen-Thüringen 1.8 m foreign employees, at 15 %, is signifi- MAIN TOWER Bremen Brandenburg Neue Mainzer Str. 52-58 0.7 m 2.5 m cantly higher than the German aver- 60311 Frankfurt am Main Lower Berlin Saxony- age of 11 %. phone: +49 69/91 32-20 24 Saxony 3.6 m 8.0 m Anhalt fax: +49 69/91 32-22 44 2.2 m North Rhine- Apart from its considerable appeal for Westphalia 17.9 m immigrants, Hesse is also a sought- Saxony Thuringia 4.1 m after location for foreign direct invest- Hesse 2.2 m 6.2 m ment. -

State and Local Immigration Regulation in the United States Before 1882

BENJAMIN J. KLEBANER STATE AND LOCAL IMMIGRATION REGULATION IN THE UNITED STATES BEFORE 1882 The absence of significant federal regulation in the area of immigration legislation until 1882 1 no more denotes a laissez-faire approach in this area than in many other aspects of American economic life. For many generations Congress had left the task of regulating the immigrant stream to the states and localities.2 The first general federal law (1882) is best understood in the context of antecedent activity on the local level. Eventually most of the seaboard states, including many without an important passenger traffic, enacted statutes dealing with immi- gration. Table I presents a brief outline of their essential features. After a consideration of certain aspects of the provisions of these laws, their administration in the major seaports will be surveyed. It will then be shown how the increasing opposition by business inter- ests to state legislation, culminating in decisions by the Supreme Court declaring such regulation unconstitutional, eventually paved the way for the 1882 Act of Congress. I. THE STATUTORY BACKGROUND Nine of the thirteen colonies reflected in their enactments the desire to protect the community from the burden of foreigners likely to 1 Federal space and sanitation requirements, however, date back to 1819. Federal legis- lation is conveniently compiled in U.S. Immigration Commission, Reports, vol. XXXIX (Washington, 1911). Cf. John Higham, Strangers in the Land (New Brunswick, N. J.; Rutgers University Press, 1955), p. 44. This article does not discuss legislation enacted in a number of states which barred foreign convicts. - The author acknowledges with gratitude the many helpful suggestions made by Professor Carter Goodrich, who super- vised his doctoral thesis "Public Poor Relief in America, 1790-1860" (Columbia University, 1952) from which much of the material for this article is taken. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY GENERAL ISSUES RELIGIONS AND PHILOSOPHY FIORANI, ELEONORA. Friedrich Engels e il materialismo dialettico. Feltrinelli Editore, Milano 1971. 272 pp. L. 3000. Engels's Anti-Diihring, Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy and Dialectics of Nature are the writings most elaborated upon by the author, who, refuting efforts to draw a line between Marx and Engels as regards their later followers, stresses Engels's contribution to Marxism. She argues that his contribution to dialectical materialism is still important for a clarification of topical issues, and makes some comments on the vicissitudes of diamat in the USSR. A chronology of Engels's life and an annotated bibliography are appended. HARTMANN, KLAUS. Die Marxsche Theorie. Eine philosophische Unter- suchung zu den Hauptschriften. Walter de Gruyter & Co, Berlin 1970. xii, 593 pp. DM 78.00. The author of this learned study undertakes a re-appraisal of Marx's theory from a purely philosophical angle. He criticizes Popper's theses (and lack of understanding of Hegelianism), but his own refutation of Marxian views brings him closer to Popper's. It is denied that a dialectical process going on in reality could justifiably be made to fit in the chain of historical necessity. Besides Marx's more philosophical writings all his major works, especially Capital, come up for discussion. Interesting are the comments on Marxist and non-Marxist evaluations of our time (Sartre, Habermas etc.). WILDERMUTH, ARMIN. Marx und die Verwirklichung der Philosophic. Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag 1970. xii, 852 pp. (in 2 vols.) Hfl. 90.00. "The synthetic unity [of inter-subjective and object-related communications] constitutes the indissoluble process of the 'social movement', the total process of human self-reproduction. -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 27-11-2019.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences offers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff, high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major cities www.hs-ansbach.de of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking distance of www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – the old town centre with its historic architecture and landmarks and hs.ansbach its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

Annual Report 1973

Annual Report 1973 National Gallery of Art 1973 ANNUAL REPORT National Gallery of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Cover photograph by Barbara Leckie; photographs on pages 14, 68, 69, 82, 88, inside back cover by Edward Lehmann; photograph on 87 by Stewart Bros; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art, Henry B. Seville, Chief. Nude Woman, Pablo Picasso, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund Woman Ironing, Edgar Degas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon CONTENTS 9 ORGANIZATION 11 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 25 APPROPRIATIONS 26 CURATORIAL ACTIVITIES 26 Acquisitions and Gifts of Works of Art 50 Lenders 52 Reports of Professional Departments 7 5 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH 77 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 79 REPORT OF THE ADMINISTRATOR 79 Employees of the National Gallery of Art 82 Attendance 82 Building Maintenance and Security 83 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 87 THE EAST BUILDING THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART The Chief Justice, The Secretary of State, The Secretary of the Warren E. Burger William P. Rogers Treasury, George P. Shultz The Secretary of the Paul Mellon, President John Hay Whitney. Smithsonian Institution, Vice-President S. Dillon Ripley Lessing J. Rosenwald Franklin D. Murphy ORGANIZATION The 36th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although technically established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately administered organization and is governed by its own Board of Trustees. -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 08-2020 EN.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences off ers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff , high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major www.hs-ansbach.de cities of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – distance of the old town centre with its historic architecture and hs.ansbach landmarks and its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

University of New South Wales 2005 UNIVERSITY of NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Project Report Sheet

BÜRGERTUM OHNE RAUM: German Liberalism and Imperialism, 1848-1884, 1918-1943. Matthew P Fitzpatrick A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 2005 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Project Report Sheet Surname or Family name: Fitzpatrick First name: Matthew Other name/s: Peter Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD. School: History Faculty: Arts Title: Bürgertum Ohne Raum: German Liberalism and Imperialism 1848-1884, 1918-1943. Abstract This thesis situates the emergence of German imperialist theory and praxis during the nineteenth century within the context of the ascendancy of German liberalism. It also contends that imperialism was an integral part of a liberal sense of German national identity. It is divided into an introduction, four parts and a set of conclusions. The introduction is a methodological and theoretical orientation. It offers an historiographical overview and places the thesis within the broader historiographical context. It also discusses the utility of post-colonial theory and various theories of nationalism and nation-building. Part One examines the emergence of expansionism within liberal circles prior to and during the period of 1848/ 49. It examines the consolidation of expansionist theory and political practice, particularly as exemplified in the Frankfurt National Assembly and the works of Friedrich List. Part Two examines the persistence of imperialist theorising and praxis in the post-revolutionary era. It scrutinises the role of liberal associations, civil society, the press and the private sector in maintaining expansionist energies up until the 1884 decision to establish state-protected colonies. Part Three focuses on the cultural transmission of imperialist values through the sciences, media and fiction. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p.