The Ecology of Waste Stabilization Ponds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margdarshika for Gram Panchayat and Paani Samiti

JJM Document - 7 Building Partnership Changing Lives Margdarshika for Gram Panchayat & VWSC to provide safe drinking water in rural households Jal Jeevan Mission (Har Ghar Jal) Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation National Jal Jeevan Mission 2020 Jal Jeevan Mission Status of household tap connecons as on 15.8.2019 Statewise Tap Connecons 0% - 10% 11% - 25% 26% - 50% 51% - 75% 76% - 99.99% 100% Source: JJM - IMIS Margdarshika for Gram Panchayat & VWSC to provide safe drinking water in rural households Jal Jeevan Mission (Har Ghar Jal) Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation National Jal Jeevan Mission 2020 15 August, 2019 ...I declare from the Red Fort today that in the days to come, we will take forward the Jal Jeevan Mission. The central and the state governments will jointly work on this Jal Jeevan Mission. We have promised to spend more than Rs. 3.50 Lakh Crore on this mission in the coming years... (Address to the Naon on 73 Independence Day, 15 August, 2019 at Red Fort, New Delhi) ..... The implementaon of this Mission is in the hands of community, all members of the village are to come together to implement this Mission...decisions on route of water pipeline, water harvesng, operaon and maintenance will be made by people themselves and our sisters have a very important role to play... (Extract from Prime Minister's address at Bundelkhand on 29 Feb, 2020) Shri Narendra Modi Prime Minister of India 15 August, 2020 (Aer one year…) Brothers and sisters, Last me, I had announced Jal Jeevan Mission. -

Macrophyte Waste Stabilization Ponds: an Option for Municipal Wastewater Treatment

International Journal of Physical Sciences Vol. 7(30), pp. 5162 - 5166, 9 August, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS DOI: 10.5897/IJPS12.309 ISSN 1992 -1950 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Macrophyte waste stabilization ponds: An option for municipal wastewater treatment Mumtaz Shah1* and Hashim Nisar Hashmi2 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Engineering and Technology (UET) Taxila, Pakistan. 2Department of Civil Engineering, University of Engineering and Technology (UET) Taxila, Pakistan. Accepted 3 August, 2012 The objective of this research is to evaluate the performance of macrophyte waste stabilization pond system for municipal wastewater collected from Taxila (Pakistan). A model of macrophyte waste stabilization pond system was operated for six trials with each trials comprising different detention times that is 3, 5, 7 and 10 days, respectively. For the treatment, locally available macrophyte (water hyacinth) was used. To evaluate the performance of macrophyte waste stabilization pond, BOD5, TDS, TSS, COD, faecal coliform and Nitrogen for the effluent from pond model were measured at each detention time of every trial after ensuring steady state conditions. The influent values of same parameters have been measured at the start of each trial as the wastewater sample was collected from the municipal sewer. The average reduction of effluent value of each parameter varies from 30 to 48%, that is BOD5 (48%), TDS (31%), TSS (30%), COD (42%), faecal coliform -

Reengineering of an Obsolete Sewage Treatment System

water Article Transformation of Waste Stabilization Ponds: Reengineering of an Obsolete Sewage Treatment System Silvânia Lucas dos Santos 1 and Adrianus van Haandel 2,* 1 Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, 59.078-970 Natal, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Campina Grande, 59.429-350 Campina Grande, Brazil * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-83-99133-0196 Abstract: Waste Stabilization Ponds (WSPs) are commonly used for sewage treatment. These systems are composed of a series of ponds: (1) anaerobic ponds, (2) facultative ponds, and (3) maturation ponds. WSPs generally produce good-quality effluent in terms of organic matter and pathogen removal, but their application has disadvantages. The most serious disadvantages are a long retention time, the release of biogas, and the impossibility of removing nutrients. A promising alternative to the use of WSPs is replacing the anaerobic pond and facultative pond with an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor, with the advantages of greatly reducing the retention time and the biogas capture. The post-treatment ponds of the UASB reactor effluent involve oxygen production and the biological consumption of carbon dioxide, which raises the pH. An experimental investigation showed that it is possible to use polishing ponds in a sequential batch regime instead of continuous flow. This modification accelerates the decay of pathogens and accelerates the increase in pH, which, in turn, facilitates the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus. This produces a good-quality effluent with low concentrations of biodegradable organic material, nutrients, and pathogens. This good- Citation: dos Santos, S.L.; quality effluent is obtained in a system without energy consumption or auxiliary materials and with van Haandel, A. -

The Removal of Faecal Coliforms in Waste Stabilization Pond Systems and Eutrophic Lakes

THE REMOVAL OF FAECAL COLIFORMS IN WASTE STABILIZATION POND SYSTEMS AND EUTROPHIC LAKES ebenezer d.o. ansa iii THE REMOVAL OF FAECAL COLIFORMS IN WASTE STABILIZATION POND SYSTEMS AND EUTROPHIC LAKES iii iv THE REMOVAL OF FAECAL COLIFORMS IN Thesis committee WASTE STABILIZATION POND SYSTEMS AND Promotor EUTROPHIC LAKES Prof. dr. H.J. Gijzen Professor of Environmental Biotechnology UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education, Delft/ Wageningen University The Netherlands Co-promotor Dr. H.J. Lubberding Senior lecturer Microbiology UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education, Delft The Netherlands Other members Prof. dr. K.A. Irvine UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education, Delft/ Wageningen University The Netherlands Prof. dr. ir. A.J.M. Stams Wageningen University The Netherlands Prof. dr. H.J. Laanbroek Utrecht University The Netherlands Prof. dr. ir. P.N.L. Lens UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education, Delft/ Wageningen University The Netherlands This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School WIMEK-SENSE v THE REMOVAL OF FAECAL COLIFORMS IN WASTE STABILIZATION POND SYSTEMS AND EUTROPHIC LAKES Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Academic Board of Wageningen University and the Academic Board of the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education for the Degree of DOCTOR to be defended in public on Tuesday 16 April, 2013 at 15:00 hrs in Delft, The Netherlands by EBENEZER D.O. ANSA Born in Swedru, Ghana v vi THE REMOVAL OF FAECAL COLIFORMS IN WASTE STABILIZATION POND SYSTEMS AND EUTROPHIC LAKES Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Academic Board of Wageningen University and the Academic Board of the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education for the Degree of DOCTOR to be defended in public on Tuesday 16 April, 2013 at 15:00 hrs in Delft, The Netherlands Taylor & Francis is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informal business by © 2013, E. -

Utilizing Different Aquatic Resources for Livelihoods in Asia

Freshwater systems/Terrestrial systems Freshwater systems/Terrestrial Systems An Overview of Rice-Based Small-Scale Aquaculture Rice-Based Aquaculture in China Enhancing the Performance of Irrigation Systems through Aquaculture Rice and Fish Culture in Seasonally Flooded Ecosystems Increasing Wild Fish Harvests by Enhancing the Rice Field Habitats Polyculture Systems: Principles and Basic Considerations Promoting Rice-Based Aquaculture in Mountainous Areas of Vietnam Aquaculture in Stream-Fed Flow-Through Ponds Short-Cycle Aquaculture in Seasonal Ponds Low-Cost Aquaculture in Undrainable Homestead Ponds Homestead Fish Culture: An Example from Bangladesh Integrating Intensive and Semi-Intensive Culture Systems to Utilize Feeding Waste Low-Cost Fertilization in Inland Pond Aquaculture Culture of Fish Food Organisms and Biofertilizers Feeds in Small-Scale Aquaculture Decentralized Seed Production Strategy for the Development of Small-Scale Aquaculture Small-Scale Eel Culture: Its Relevance for Rural Households Small-scale Macrobrachium Culture in Bangladesh Culture of Chinese Mitten- Handed Crabs Aquaculture and Sewage Water Treatment Water Quality Management for Freshwater Fish Culture 1 of 135 2 of 135 An Overview of Rice-Based Small-Scale Aquaculture Asian countries as rice-fish societies Many countries in Asia can be called "rice-fish societies" in the sense that rice is the staple crop for basic subsistence, while fish is the main source of animal protein. The availability of rice and fish has long been associated with prosperity and food security. In Thailand, for example, the early inscription of the 13th century king, Ramkhamhaeng, states "in the waters are fish and in the field is rice" as an indicator of wealth and stability. -

![IS 5611 (1987): Code of Practice for Construction of Waste Stabilization Ponds (Faculative Type) [CED 24: Public Health Engineering.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1315/is-5611-1987-code-of-practice-for-construction-of-waste-stabilization-ponds-faculative-type-ced-24-public-health-engineering-1771315.webp)

IS 5611 (1987): Code of Practice for Construction of Waste Stabilization Ponds (Faculative Type) [CED 24: Public Health Engineering.]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 5611 (1987): Code of Practice for Construction of Waste Stabilization Ponds (Faculative Type) [CED 24: Public Health Engineering.] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS : 5811 - 1987 ( Asattlrmed 1992 ) Indian Standard CODE OF PRACTICE FOR CONSTRUCTION OF WASTE STABILIZATION PONDS ( FACULATIVE TYPE ) ( First Revision ) ( First Reprint JANUARY 1998 ) UDC 628.357.1 : 006.76 0 Copyright 1987 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 Gr 5 October 1987 IS : 5611- 1987 Indian Standard CODE OF PRACTICE FOR CONSTRUCTION OF WASTE STABILIZATION PONDS ( FACULATIVE TYPE ) (First Revision) Water Supply and Sanitation Sectional Committee, BDC 24 Chairman Representing SHRI J. -

Wastewater Stabilization Ponds (WSP) for Wastewater Treatment - S

WATER AND WASTEWATER TREATMENT TECHNOLOGIES – Vol. II - Wastewater Stabilization Ponds (WSP) for Wastewater Treatment - S. Phuntsho, H.K. Shon, S. Vigneswaran, and J. Kandasamy WASTEWATER STABILIZATION PONDS (WSP) FOR WASTEWATER TREATMENT S. Phuntsho, H.K. Shon, S. Vigneswaran and J. Kandasamy Faculty of Engineering, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia Keywords: wastewater stabilization ponds (WSP), anaerobic ponds, facultative ponds, maturation ponds, wastewater treatment, appropriate treatment, developing countries, upgrading of WSP, wetlands, rock filters, land treatment, wetlands Contents 1. Introduction 2. Advantages and Disadvantages of WSP 3. Types of WSP 3.1 Anaerobic Ponds 3.2 Facultative Ponds 3.3 Maturation Ponds 4. Process Design of WSP 4.1 Design parameters 4.2 Design of Anaerobic Ponds 4.3 Design of Facultative Ponds 4.4 Design of Maturation Ponds 4.4.1 Design of Maturation Ponds for Faecal Coliform (FC) removal 4.4.2 Design of Maturation Ponds for Helminth Egg Removal 4.4.3 BOD Removal by Maturation Ponds 4.4.4. Design of Maturation Ponds for Nutrient Removal 5. Physical Design of WSP 6. Upgrading of Waste Stabilization Ponds 6.1 Upgrading WSP Effluent with Treatment Wetlands 6.1.1 Natural Wetlands 6.1.2 Constructed Wetlands 6.2 Upgrading Facultative WSP Effluents Using Rock Filters 6.3 Upgrading of WSP with Land Applications 6.3.1 Slow Rate 6.3.2 RapidUNESCO Infiltration (RI) – EOLSS 6.3.3 Overland flow 6.4 Upgrading of WSP with Intermittent Sand Filtration 6.5 Upgrading ofSAMPLE WSP with Hyacinth and Duckweed CHAPTERS 6.6 Upgrading Using Attached Growth Wastewater Stabilization Ponds (AGWSP) 6.7 Upgrading of WSP with Pond Aeration 6.8 Upgrading WSP to Baffled Reactor 7. -

Waste Stabilization Ponds

GLOBAL WATER PATHOGEN PROJECT PART FOUR. MANAGEMENT OF RISK FROM EXCRETA AND WASTEWATER WASTE STABILIZATION PONDS Matthew Verbyla San Diego State University San Diego, United States Marcos von Sperling Federal University of Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte, Brazil Ynoussa Maiga University of Ouagadougou Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso Copyright: This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Citation: Verbyla, M., von Sperling, M., Maiga, Y. 2017. Waste Stabilization Ponds. In: J.B. Rose and B. Jiménez- Cisneros, (eds) Global Water Pathogens Project. http://www.waterpathogens.org (C. Haas, J. Mihelcic and M. Verbyla) (eds) Part 4 Management Of Risk from Excreta nad Wastewater) http://www.waterpathogens.org/book/waste-stabilization-ponds Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI, UNESCO. Acknowledgements: K.R.L. Young, Project Design editor; Website Design (http://www.agroknow.com) Published: March 13, 2017, 1:12 pm, Updated: September 7, 2017, 10:56 am Waste Stabilization Ponds Summary energy inputs. -

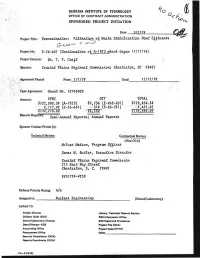

Qc 250 � • -V3g,466.00 Reports Requhed

GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION SPONSORED PROJECT INITIATION Date: 312479 Project Title: DemonztAation; WaAte Stabilization Pond E liguent6 "*". Project No: E-26-641 CContinuation of A-1923 which began 11/17/761 Project Director: Pt. T. F. CAag Sponsor: Coastae Minn Regionat Complizaion; Chaxeezton, SC 294Q1 Agreement Period: From 1/1/19 Until 11/17/79 Type Agreement: Grant No. 10740003 Amount: CPRC GU TOTAL $122,098.58 [A-19231 $7,736 •(E-862-0011 $124,834.58 8,117.42 [E-26-6411 514 CE-26-3211 - 8,63%42 130,276.00 ..qc 250 • -V3g,466.00 Reports Requhed. semi-Ann clot.. RepoktA; Annwzt Reports Sponsor Contact Person (s): Technical Matters Contractual Matters (thru OCA) MaVek (tatzon, Pnognam 066icek Jamey Al. Buttek, 'Executive Dikectox CoaAtat Mainz Reg.LonaL Commi4Aibn - 215 EaAt Bay Stiieet Chakteaton,.S. C. 29401 803/724-4250 Defense Priority Rating: n/a Assigned to: Nucteak Engineeking (School/Laboratory) COPIES TO: Project Director Library. Technical Reports Section Division Chief (EES) EES Information Office School/Laboratory Director EES Reports & Procedures Dean/Director—EES Project File (OCA) Accounting Office Project Code (GTRI) Procurement Office Other Security Coordinator (OCA) Reports Coordinator COCA) GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION SPONSORED PROJECT TERMINATION Date: September 21, 1980 " Project Title: Demonstration: Filtration of Waste Stabilization Pond Effluents Project No: E-26-641 (Continuation of A-1923 which began 11/17/76) Project Director: Dr. T. F. Craft Sponsor: Coastal Plains Regional Commission; Charleston, SC 29401 Effective Termination Date: 9/1/80 Clearance of Accounting Charges: - _ Grant/Contract Closeout Actions Remaining: None Final Invoice and Closing Documents Final Fiscal Report Final Report of Inventions Govt. -

Sanitation Safety Planning: Manual for Safe Use and Disposal of Wastewater, Greywater and Excreta

SANITATION SAFETY PLANNING MANUAL FOR SAFE USE AND DISPOSAL OF WASTEWATER, GREYWATER AND EXCRETA SANITATION SAFETY PLANNING MANUAL FOR SAFE USE AND DISPOSAL OF WASTEWATER, GREYWATER AND EXCRETA WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Sanitation safety planning: manual for safe use and disposal of wastewater, greywater and excreta. 1.Water Supply. 2.Agriculture. 3.Aquaculture. 4.Sewage. 5.Wastewater. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154924 0 (NLM classification: WA 675) Reprinted in 2016 with changes © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/ index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Stabilization Pond for Wastewater Treatment

European Scientific Journal May 2013 edition vol.9, No.14 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 STABILIZATION POND FOR WASTEWATER TREATMENT Prof. Dr. Mohammed Ali I. Al-Hashimi Eng. Hayder Talee Hussain Environment Branch, Building and construction Dep., University of Technology, Iraq Abstract This research is concerned with study and check the suitability of waste stabilization ponds (WSPs) for treating wastewater in Al-Dewaniyah province by taking a sample of community of 10000 population. Experimental work had three cases depending on many considerations such as economical and specification of final effluent. A model of two ponds (facultative and aerobic) in series was used as first case of experimental work. Then third pond with aeration process to aerobic pond were added to the series as second case to improve the effluent. At last, sand filter was used to polish the final effluent from aerobic pond. The three ponds had the same surface area (5.75m*2m) but with different depths, where it was 2m for anaerobic pond, 1.5m for facultative pond and 0.75m for aerobic pond. From the tests taken for the three cases, the results obtained for the last two cases were much better when compared with first case. Sand filter contributed in improving final effluent by decreasing total suspended solid (TSS) also in increasing removal efficiency of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD). At the end, the results of this work could be an invitation to use waste stabilization pond for wastewater treatment in rural areas or even small communities but it may need more examinations to get best results. -

Low-Cost Technologies for Mining Wastewater Treatment

Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering B 6 (2017) 391-405 doi:10.17265/2162-5263/2017.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Low-Cost Technologies for Mining Wastewater Treatment Mike Agbesi Acheampong1 and Ebenezer David Okwaning Ansa2 1. Department of Chemical Engineering, Kumasi Technical University, Kumasi, Ghana 2. Water Research Institute, Council for Scientific & Industrial Research, Accra, Ghana Abstract: The mining industry has contributed tremendously to the global economy. However, waste generated by this activity poses many challenges. Current low-cost technologies for the removal of heavy metals from mining wastewater include biosorption, adsorption, CWs (Constructed Wetlands) and waste stabilization ponds. This chapter focuses on sustainable mining wastewater treatment technologies with emphasis on gold mining wastewater. It discusses the technical and environmental challenges associated with mining effluent treatment, process conditions for optimum plant performance, efficiency, limitations and the economics of treating mining wastewater. The overall treatment cost of metal contaminated wastewater depends on the process employed and the local conditions. In general, technical applicability, cost-effectiveness and plant simplicity are the key factors in selecting the most suitable treatment method. Proper management of the spent biosorbent and solid wastes generated is also discussed. Key words: Removal, heavy metal, biosorption, waste stabilization pond, CW (Constructed Wetland), mining wastewater. 1. Introduction new technology