New Work: Christopher Wool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

Robert Gober the Heart Is Not a Metaphor

How in the fuck are you supposed to hit that shit? —Mickey Mantle ROBERT GOBER THE HEART IS NOT A METAPHOR Edited by Ann Temkin Essay by Hilton Als With a Chronology by Claudia Carson, Robert Gober, and Paulina Pobocha And an Afterword by Christian Scheidemann The Museum of Modern Art, New York CONTENTS 9 Foreword Glenn D. Lowry 10 Published by The Museum of Robert Gober: An Invitation Modern Art, Ann Temkin 11 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019-5497 Published on the occasion of www.moma.org 20 the exhibition Robert Gober: The I Don’t Remember Heart Is Not a Metaphor, at The Distributed in the United States Hilton Als Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Canada by ARTBOOK | October 4, 2014–January 18, D.A.P., New York 2015, organized by Ann Temkin, 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd floor 92 The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis New York, NY 10013 Chronology Chief Curator of Painting and www.artbook.com Claudia Carson and Paulina Pobocha with Robert Gober Sculpture, and Paulina Pobocha, © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art Assistant Curator, Department of Distributed outside the United Painting and Sculpture Hilton Als’s essay “I Don’t States and Canada by Thames & 246 Remember” is © 2014 Hilton Als. Hudson ltd Robert Gober’s Painted Sculpture 181A High Holborn Christian Scheidemann Thom Gunn’s poem “Still Life,” London WC1V 7QX The exhibition is made possible by from his Collected Poems, is www.thamesandhudson.com Hyundai Card. © 1994 Thom Gunn. Reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Front cover: Robert Gober 256 List of Works Illustrated Major support is provided by the Ltd and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, working on Untitled, 1995–97, in 262 Exhibition History Henry Luce Foundation, Maja Oeri LLC. -

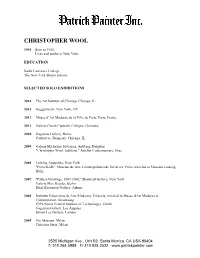

Christopher Wool

CHRISTOPHER WOOL 1955 Born in 1955. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION Sarah Lawrence College The New York Studio School. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2013 Guggenheim, New York, NY 2012 Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France 2011 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany 2010 Gagosian Gallery, Rome Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2009 Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium "Christopher Wool: Editions," Artelier Contemporary, Graz 2008 Luhring Augustine, New York "Porto-Köln," Museum de Arte Contemporanea de Serralves, Porto, traveled to Museum Ludwig, Köln; 2007 "Pattern Paintings, 1987-2000," Skarstedt Gallery, New York Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens 2006 Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia; traveled to Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles Simon Lee Gallery, London 2005 Gio Marconi, Milan Christian Stein, Milan 2525 Michigan Ave., Unit B2, Santa Monica, CA USA 90404 T/ 310 264 5988 F/ 310 828 2532 www.patrickpainter.com 2004 Camden Arts Centre, London Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Luhring Augustine, New York Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo 2003 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2002 "Crosstown Crosstown," Le consortium, Dijon; traveled to Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, Scotland Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin 2001 "9th Street Run Down," 11 Duke Street, London; traveled to Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Secession, Vienna Luhring Augustine, -

Katherine Brinson. "Trouble Is My Business."

Katherine Brinson TROUBLE IS MY BUSINESS ONE OF THE FIRST public descriptions of Christopher Wool’s art which they seem to deny.”2 As Wool’s oeuvre has evolved, could just as easily provide the last word. Written as the press it has become clear that this evasive quality stems from a fun- release for his 1986 show at Cable Gallery in New York, damental rejection of certainty or resolution that serves as the when Wool was on the brink of creating the body of work conceptual core of the work as well as its formal underpinnings. that marked the breakthrough to his mature career, it augurs A restless search for meaning is already visualized within the his development with strange prescience: paintings, photographs, and works on paper that constitute the artist’s nuanced engagement with the question of how to Wool’s work contains continual internal/external make a picture. debate within itself. At one moment his work will display self-denial, at the next moment solipsism. ALTHOUGH IN RECENT YEARS Wool has spent much of his time Shifting psychological states, false fronts, shadows amid the open landscape of West Texas, from the outset his of themselves, justify their own existence. Wool’s work has been associated with an abrasive urban sensibility. work locks itself in only to deftly escape through His identity was forged in two locales teeming with avant- sleight of hand. The necessity to survive the moment garde currents: the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s and at all costs, using its repertoire of false fronts and downtown New York in the 1970s. -

Christopher Wool Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Christopher Wool Bibliography Selected Books and Catalogues: 2018 Wool, Christopher. Yard. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. 2017 Siegel, Katy and Christopher Wool. Painting Paintings (David Reed) 1975. New York: Gagosian. Wool, Christopher. Westtexaspsychosculpture. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. 2013 Brinson, Katherine et al. Christopher Wool. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. 2012 Cherix, Christophe. Print/Out: 20 Years in Print. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Corbett, John and Fabrice Hergott. Christopher Wool. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. ----------. The Painting Factory: Abstraction After Warhol. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art. 2011 ----------. Art in the Streets. New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc. in association with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Barrett, Terry. Making Art: Form and Meaning. New York: McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. ----------. Defining Contemporary Art – 25 Years in 200 Pivitol Artworks. London: Phaidon Press Limited. Doring, Jurgen. Power to the Imagination: Artists, Posters and Politics. Munich: Hirmer Verlag GmbH. Holzwarth, Hans Werner, and Laszlo Taschen, eds. Modern Art Volume 2: 1945-2000. Cologne: Taschen, 2011. Molesworth, Helen. This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s. New Haven and London: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and Yale University Press. Pincio, Tommaso. Christopher Wool: Roma Termini. New York: Gagosian Gallery. ----------. Peace Press Graphics: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change. Long Beach: University Art Museum, California State University. 2010 Bondaroff, Aaron, Glenn O’Brien, and James Jebbia. Supreme. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. Cooke, Lynne, Douglas Crimp, and Kristin Poor. Mixed Use, Manhattan: Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. -

Larry Johnson

LARRY JOHNSON born 1959, Long Beach, CA lives and works in Los Angeles, CA EDUCATION 1984 MFA, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA 1982 BFA, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2019 Larry Johnson & Asha Schechter, Jenny's, Los Angeles, CA 2015 *Larry Johnson: On Location, curated by Bruce Hainley and Antony Hudek, Raven Row, London, England 2009 *Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA 2007 Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, CA Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York, NY 2001 New Photographs, Cohan, Leslie & Browne, New York, NY 2000 The Thinking Man’s Judy Garland and Other Works, Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, CA Modern Art Inc., London, England 1998 Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne, Germany I-20 Gallery, New York, NY Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1996 *Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 1995 Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] www.davidkordanskygallery.com T: 323.935.3030 F: 323.935.3031 1994 Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1992 Rudiger Shottle, Paris, France Patrick de Brok Gallery, Knokke, Belgium 1991 303 Gallery, New York, NY Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA Johnen & Schottle, Cologne, Germany 1990 303 Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Isabella Kacprzak, Cologne, Germany Stuart Regen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1989 303 Gallery, New York, NY 1987 Le Case d’ Arte, Milan, Italy 303 Gallery, New York, NY Galerie Isabella Kacprzak, Stuttgart, Germany Kuhlenschmidt/Simon Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 1986 303 Gallery, New York, NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2021 Winter of Discontent, 303 Gallery, New York, NY The Going Away Present, Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2020 Made in L.A. -

Untitled, 1987

October 25, 2013–January 22, 2014 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit Since his emergence as an artist in the 1980s, Christopher Wool (b. 1955) has forged an agile, highly focused practice that ranges across processes and mediums, paying special attention to the complexities of painting. Filling the museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda and an adjacent gallery, this exhibition explores the artist’s nuanced engagement with the question of how to make a picture. This Resource Unit focuses on various aspects of Wool’s work and provides techniques for exploring both the visual arts and other areas of the curriculum. This guide also is available on the museum’s website at guggenheim.org/artscurriculum with images that can be downloaded or projected for classroom use. The images may be used for educational purposes only and are not licensed for commercial applications of any kind. Before bringing your class to the Guggenheim, we invite you to visit the exhibition, read the guide, and decide which aspects of the exhibition are most relevant to your students. For more information on scheduling a visit for your students, please call 212 423 3637. For the educator, this exhibition provides a perfect opportunity to invite students of all ages to join in a meaningful journey into a visually rich and stimulating world. Christopher Wool is generously supported by Guggenheim Partners, LLC. Major support is provided by the Leadership Committee for the exhibition: Luhring Augustine, New York; The Brant Foundation, Inc.; Thompson Dean Family Foundation; Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson; Gagosian Gallery; Danielle and David Ganek; Brett and Dan Sundheim; and Zadig & Voltaire. -

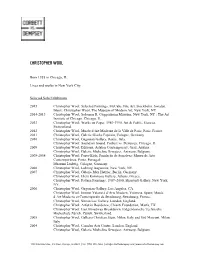

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and Works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, London, England 2019 Christopher Wool, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* Maybe Maybe Not : Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection, Hill Art Foundation, New York, NY. 2018 Christopher Wool : A New Sculpture, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool : Highlights from the Hill Art Collection, H Queens, Hong Kong. 2017 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Text Without Message, Philbrook Downtown, Tulsa, OK. 2016 Christopher Wool, Daros Collection at Fondation Beyeler, Hurden, Switzerland. 2015 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY; Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2013-2014 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.* 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France.* 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. * A catalogue was published with this exhibition. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy.* Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2008-2009 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany.* 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. -

Architectsnewspaper 6.8.2004 Going to Seed

lit ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER MoMA 049695 6.8.2004 06/16 $3.95 WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 00 —I DILLER SCOFIDIO LU + RENFRO: NYC'S NEW URBAN O MASTERMINDS SUMMER READING REM FOR PRESIDENT? EAVESDROP USA 37 CURBSIDE DIARY CLASSIFIEDS ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN SHOPTALK FEATURED ON NEW BATCH OF STAMPS MODERNIST GARDENS IN THE New York's modernist open spaces, such VILLAGE UNDER THREAT as the plaza of the Seagram Building and the courtyard of the Lever House, are well known, NEW LAW TO REQUIRE Bucky s Dome but the city's legacy of modernist gardens is MANDATORY CERTIFICATION more obscure and potentially under threat. FOR INTERIOR DESIGNERS R. Buckminster Fuller's bald geodesic head In Greenwich Village, two major examples— is about to appear on 96 million first-class GOING the formal garden that I. M. Pei designed in INTERIOR postage stamps. In addition to Bucky's 1965 to accompany his University Village tessellated head, the designs of Isamu towers between Houston, La Guardia and Noguchi, McKim, Mead, and White, Walter Bleecker streets, and the adjacent Washington DESIGNERS Netsch and Skidmore Owings and Merrill Square Village designed in 1959 by land• (SOM), and Rhode Island architect scape architecture firm Sasaki, Walker and GET SERIOUS Friedrich St. Florian will be appear on TO Associates—face uncertain futures. Both stamps this summer. surround New York University housing. The United States Postal Service (USPS) Apart from its value as a leafy respite, the The old turf dispute between New York receives nearly 50,000 requests a year for gardens of University Village are noteworthy. -

Wool CV1.Pdf

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955 in Chicago, IL. Lives and works in New York City. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2014-2013 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY ; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d‘Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France. 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL. 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2009-2008 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany. Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. Christopher Wool: Pattern Paintings, 1987–2000, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY. 2006 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Christopher Wool, Institut Valencià d‘Arte Modern, Valencia, Spain; Musée d‘Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France. Christopher Wool, Simon Lee Gallery, London, England. Christopher Wool: Artist in Residence, Chianti Foundation, Marfa, TX. Christopher Wool: East Broadway Breakdown, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. 2005 Christopher Wool, Galleria Christian Stein, Milan, Italy and Gió Marconi, Milan, Italy. 2004 Christopher Wool, Camden Arts Centre, London, England. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 1120 N Ashland Ave., 3rd Floor, Chicago, IL 60622 | Tel.