Untitled, 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Work: Christopher Wool

[HRl�TOPHf R WOOl NEW WORK SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW WORK: CHRISTOPHER WOOL JULY 6 - SEPTEMBER 3, 1989 Although he has explored other art forms, including film,what Christopher Wool considers his mature work began with paintings he made in 1984. At that time, he was dissatisfied with the work he was producing (for example, a painting called Bigger Questions, which was simply a question mark on its side). Like many artists before him, he began to investigate the basic processes of painting itself, "strug gling to find some kind of meaningful imagery."1 A work he called Zen Exercise con sisted of three large, violent pours of paint. Looking back today he considers this work crucial because the pours were random, and he was "looking for location:• In the following year, with an enamel on plywood painting entitled Houdini, Wool continued his arbitrary paint application by dripping and spattering white paint onto a black surface. At first glance, Houdini looks like a Jackson Pollock achieved by recourse to the methods of John Cage: the evidently random drops of paint occasionally coalesce into larger, driplike patterns. One suspects that this adventitious painterliness was both too lush and too ambiguous for the artist, because for the next two years he produced paintings in which the application of paint was rigorously even. The result was paintings with allover compositions that although random were everywhere uniform, with no runs and only occasional larger dots of paint where one drop collided with another: Standing before such paintings for the first time is a curious experience. -

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

Robert Gober the Heart Is Not a Metaphor

How in the fuck are you supposed to hit that shit? —Mickey Mantle ROBERT GOBER THE HEART IS NOT A METAPHOR Edited by Ann Temkin Essay by Hilton Als With a Chronology by Claudia Carson, Robert Gober, and Paulina Pobocha And an Afterword by Christian Scheidemann The Museum of Modern Art, New York CONTENTS 9 Foreword Glenn D. Lowry 10 Published by The Museum of Robert Gober: An Invitation Modern Art, Ann Temkin 11 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019-5497 Published on the occasion of www.moma.org 20 the exhibition Robert Gober: The I Don’t Remember Heart Is Not a Metaphor, at The Distributed in the United States Hilton Als Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Canada by ARTBOOK | October 4, 2014–January 18, D.A.P., New York 2015, organized by Ann Temkin, 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd floor 92 The Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis New York, NY 10013 Chronology Chief Curator of Painting and www.artbook.com Claudia Carson and Paulina Pobocha with Robert Gober Sculpture, and Paulina Pobocha, © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art Assistant Curator, Department of Distributed outside the United Painting and Sculpture Hilton Als’s essay “I Don’t States and Canada by Thames & 246 Remember” is © 2014 Hilton Als. Hudson ltd Robert Gober’s Painted Sculpture 181A High Holborn Christian Scheidemann Thom Gunn’s poem “Still Life,” London WC1V 7QX The exhibition is made possible by from his Collected Poems, is www.thamesandhudson.com Hyundai Card. © 1994 Thom Gunn. Reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Front cover: Robert Gober 256 List of Works Illustrated Major support is provided by the Ltd and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, working on Untitled, 1995–97, in 262 Exhibition History Henry Luce Foundation, Maja Oeri LLC. -

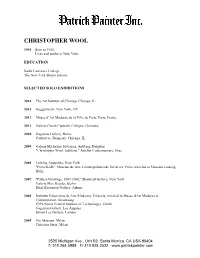

Christopher Wool

CHRISTOPHER WOOL 1955 Born in 1955. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION Sarah Lawrence College The New York Studio School. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2013 Guggenheim, New York, NY 2012 Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France 2011 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany 2010 Gagosian Gallery, Rome Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2009 Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium "Christopher Wool: Editions," Artelier Contemporary, Graz 2008 Luhring Augustine, New York "Porto-Köln," Museum de Arte Contemporanea de Serralves, Porto, traveled to Museum Ludwig, Köln; 2007 "Pattern Paintings, 1987-2000," Skarstedt Gallery, New York Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens 2006 Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia; traveled to Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles Simon Lee Gallery, London 2005 Gio Marconi, Milan Christian Stein, Milan 2525 Michigan Ave., Unit B2, Santa Monica, CA USA 90404 T/ 310 264 5988 F/ 310 828 2532 www.patrickpainter.com 2004 Camden Arts Centre, London Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Luhring Augustine, New York Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo 2003 Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2002 "Crosstown Crosstown," Le consortium, Dijon; traveled to Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, Scotland Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin 2001 "9th Street Run Down," 11 Duke Street, London; traveled to Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp Secession, Vienna Luhring Augustine, -

Katherine Brinson. "Trouble Is My Business."

Katherine Brinson TROUBLE IS MY BUSINESS ONE OF THE FIRST public descriptions of Christopher Wool’s art which they seem to deny.”2 As Wool’s oeuvre has evolved, could just as easily provide the last word. Written as the press it has become clear that this evasive quality stems from a fun- release for his 1986 show at Cable Gallery in New York, damental rejection of certainty or resolution that serves as the when Wool was on the brink of creating the body of work conceptual core of the work as well as its formal underpinnings. that marked the breakthrough to his mature career, it augurs A restless search for meaning is already visualized within the his development with strange prescience: paintings, photographs, and works on paper that constitute the artist’s nuanced engagement with the question of how to Wool’s work contains continual internal/external make a picture. debate within itself. At one moment his work will display self-denial, at the next moment solipsism. ALTHOUGH IN RECENT YEARS Wool has spent much of his time Shifting psychological states, false fronts, shadows amid the open landscape of West Texas, from the outset his of themselves, justify their own existence. Wool’s work has been associated with an abrasive urban sensibility. work locks itself in only to deftly escape through His identity was forged in two locales teeming with avant- sleight of hand. The necessity to survive the moment garde currents: the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s and at all costs, using its repertoire of false fronts and downtown New York in the 1970s. -

Christopher Wool Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Christopher Wool Bibliography Selected Books and Catalogues: 2018 Wool, Christopher. Yard. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. 2017 Siegel, Katy and Christopher Wool. Painting Paintings (David Reed) 1975. New York: Gagosian. Wool, Christopher. Westtexaspsychosculpture. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. 2013 Brinson, Katherine et al. Christopher Wool. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. 2012 Cherix, Christophe. Print/Out: 20 Years in Print. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Corbett, John and Fabrice Hergott. Christopher Wool. Berlin: Holzwarth Publications. ----------. The Painting Factory: Abstraction After Warhol. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art. 2011 ----------. Art in the Streets. New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc. in association with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Barrett, Terry. Making Art: Form and Meaning. New York: McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. ----------. Defining Contemporary Art – 25 Years in 200 Pivitol Artworks. London: Phaidon Press Limited. Doring, Jurgen. Power to the Imagination: Artists, Posters and Politics. Munich: Hirmer Verlag GmbH. Holzwarth, Hans Werner, and Laszlo Taschen, eds. Modern Art Volume 2: 1945-2000. Cologne: Taschen, 2011. Molesworth, Helen. This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s. New Haven and London: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and Yale University Press. Pincio, Tommaso. Christopher Wool: Roma Termini. New York: Gagosian Gallery. ----------. Peace Press Graphics: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change. Long Beach: University Art Museum, California State University. 2010 Bondaroff, Aaron, Glenn O’Brien, and James Jebbia. Supreme. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. Cooke, Lynne, Douglas Crimp, and Kristin Poor. Mixed Use, Manhattan: Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. -

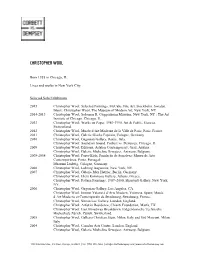

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and Works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955, Chicago, IL Lives and works in New York, NY and Marfa, TX SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, London, England 2019 Christopher Wool, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* Maybe Maybe Not : Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection, Hill Art Foundation, New York, NY. 2018 Christopher Wool : A New Sculpture, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool : Highlights from the Hill Art Collection, H Queens, Hong Kong. 2017 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Text Without Message, Philbrook Downtown, Tulsa, OK. 2016 Christopher Wool, Daros Collection at Fondation Beyeler, Hurden, Switzerland. 2015 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY; Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2013-2014 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.* 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France.* 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. * A catalogue was published with this exhibition. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy.* Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL.* 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2008-2009 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany.* 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany.* Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. -

Wool CV1.Pdf

CHRISTOPHER WOOL Born 1955 in Chicago, IL. Lives and works in New York City. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden. Inbox: Christopher Wool, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. 2014-2013 Christopher Wool, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY ; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2013 Christopher Wool: Works on Paper, 1989-1990, Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland. 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d‘Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France. 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany. 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Christopher Wool: Sound on Sound, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL. 2009 Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 2009-2008 Christopher Wool: Porto-Köln, Fundação de Serralves: Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, Portugal; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY. 2007 Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany. Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece. Christopher Wool: Pattern Paintings, 1987–2000, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY. 2006 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Christopher Wool, Institut Valencià d‘Arte Modern, Valencia, Spain; Musée d‘Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France. Christopher Wool, Simon Lee Gallery, London, England. Christopher Wool: Artist in Residence, Chianti Foundation, Marfa, TX. Christopher Wool: East Broadway Breakdown, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. 2005 Christopher Wool, Galleria Christian Stein, Milan, Italy and Gió Marconi, Milan, Italy. 2004 Christopher Wool, Camden Arts Centre, London, England. Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium. 1120 N Ashland Ave., 3rd Floor, Chicago, IL 60622 | Tel. -

David Zwirner London W1S 4EZ Telephone 020 3538 3165

24 Grafton Street Fax 020 7409 3075 David Zwirner London W1S 4EZ Telephone 020 3538 3165 For immediate release RAOUL DE KEYSER Drift November 26, 2015 – January 23, 2016 Private view: Wednesday, November 25, 6 – 8 PM Press preview with curator Ulrich Loock: 5 PM David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings by Raoul De Keyser, marking the artist’s first show with the gallery in London. On view at 24 Grafton Street, Raoul De Keyser: Drift is organized around a group of twenty-two works completed shortly before his death in October 2012, and known as The Last Wall. Together, they revisit some of the major subjects that occupied the artist throughout his nearly fifty-year long career, including the landscape of the Belgian lowlands where he grew up and lived his entire life, the inconspicuous things close at hand, and the partition of the picture plane. These paintings will be accompanied by a careful selection of works from the 1990s onwards that are likewise representative of these subjects and further contextualize the later series. The exhibition marks De Keyser’s first major show in London since his critically acclaimed 2004 traveling survey of paintings at the Photo by Jef Van Eynde Whitechapel Gallery. De Keyser’s subtly evocative paintings are at once straightforward and cryptic, abstract and figurative. Made up of simple shapes and marks, they invoke spatial and figural illusions, yet remain elusive of any descriptive narrative. Despite—or precisely because of—their sparse gesturing, De Keyser’s works convey a visual intensity that inspires prolonged contemplation. -

Christopher Wool

CHRISTOPHER WOOL BIOGRAPHY Born 1955 in Chicago, IL Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1969-1972 B.A, Sarah Lawrence College, New York, NY 1973 Painting Course, New York Studio School, New York, NY Painting Course, New York University, New York, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Maybe Maybe Not: Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection, Hill Art Foundation, New York, NY 2018 Christopher Wool: A New Sculpture, Luhring Augustine, Brooklyn, NY Christopher Wool: Highlights from the Hill Art Collection, Hill Art Foundation, H Queen’s Atrium, Hong Kong 2017 Christopher Wool: Text Without Message, Philbrook Downtown, Tulsa, OK Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany 2015 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY Christopher Wool: Selected Paintings, McCabe Fine Art, Stockholm, Sweden Inbox: Christopher Wool, MoMA, New York, NY 2013 Christopher Wool, Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY. This exhibition travelled in 2014 to Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (exh. cat.) 2012 Christopher Wool, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France 2011 Christopher Wool, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, Germany 2010 Christopher Wool, Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy Christopher Wool, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2009 Christopher Wool, Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp, Belgium Christopher Wool: Editions, Artelier Contemporary, Graz, Austria 2008 Christopher Wool, Luhring Augustine Gallery, New York, NY Christopher Wool. Porto – Köln, curated by Ulrich Loock and Julia Friedrich, Museu Serralves, Porto, Portugal. This exhibition travelled to the Museum Ludwig (exh. cat). 2007 Pattern Paintings 1987-2000, Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY (exh. cat) Christopher Wool, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany (exh. cat) Christopher Wool, Eleni Koroneou Gallery, Athens, Greece 2006 Christopher Wool, Simon Lee Gallery, London, UK Christopher Wool, ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich, Germany Christopher Wool, IVAM Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia, Spain (exh. -

Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection February 9—June 28

239 10th Avenue New York, NY 10001 Maybe Maybe Not: Christopher Wool and the Hill Collection February 9—June 28, 2019 Maybe Maybe Not presents an emblematic selection of the work of American artist Christopher Wool. It inaugurates the exhibition program of the Hill Art Foundation, a cultural center conceived to offer broad public access to the seminal collection of contemporary and historical works assembled by J. Tomilson and Janine Hill over the past four decades. Since coming to prominence in the 1980s, Christopher Wool has conducted a richly nuanced investigation of the possibilities of pictorial composition. This presentation of paintings, works on paper, photographs and prints encapsulates the evolution of the artist’s career, ranging from early experiments with readymade forms in his pattern and word paintings to more recent explorations of spontaneous gesture and digital intervention. Threading through Wool’s use of stenciled flowers, wildly looping spray paint, passages of violent erasure, and silkscreened apparitions of his own past imagery is a tension between freedom and constraint that has always animated his work. Photography has long played an integral role in Wool’s practice, and this exhibition debuts two new photographic series. Whereas his previous work in the medium focused on scenes of alienation and degradation in the urban landscape, this more recent production documents the landscape of West Texas, where the artist has a home. Employing a disarming convergence of exposures, Yard locates unexpected sculptural vignettes in the ramshackle detritus surrounding semi-rural dwellings, while Road captures empty stretches of rough, overgrown track in which a destination is always deferred. -

Josh Smith Born 1976 in Okinawa, Japan

This document was updated March 3, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Josh Smith Born 1976 in Okinawa, Japan. Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. EDUCATION 1996-1998 B.F.A., University of Tennessee, Knoxville 1994-1996 Miami University, Oxford, Ohio SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Josh Smith: Spectre, David Zwirner, New York concurrently on view at David Zwirner, London Josh Smith: High As Fuck, David Zwirner Offsite/Online: Josh Smith Studio, Brooklyn, New York [online presentation] Josh Smith: Life, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich 2019 Josh Smith: Emo Jungle, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] Josh Smith: Finding Emo, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels 2018 Josh Smith: I Will Carry the Weight, Massimo De Carlo, London Josh Smith: Understand Me, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, New York 2017 Josh Smith: You Walk On Ahead, Go As Fast As You Want. I’ll Follow Along Slowly. I Know The Road Well, Standard (Oslo), Oslo 2016 Josh Smith, Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, Germany Josh Smith: Fishes, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels [catalogue] 2015 Josh Smith, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich Josh Smith, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma, Rome Josh Smith: Cold Fusion, Hiromi Yoshii Roppongi, Tokyo Josh Smith/Dieter Roth, Cahiers d’Art, Paris [organized by Galerie Eva Presenhuber] [two-person exhibition] Josh Smith: Sculpture, Luhring Augustine, New York 2014 Josh Smith: Unsolved Mystery, Massimo De Carlo, Milan 2013 24 Hours, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich Josh Smith, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, New York Josh