Class Actions Against Banks Under the New Israeli Law on Class Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Sheet:Middle East and Africa ESG Screened Index Equity Sub

EMEA_INST Managed Pension Funds Limited Middle East and Africa ESG Screened Index Equity Sub-Fund Equities 30 June 2021 Fund Objective Performance ® The Sub-Fund aims to track the FTSE Developed Annualised Fund Benchmark Difference Middle East and Africa ex Controversies ex CW 1 Year (%) 23.30 23.28 0.01 Index, or its recognised replacement or equivalent. 3 Year (%) 4.75 4.84 -0.09 Investment Strategy 5 Year (%) 0.78 0.89 -0.11 The Sub-Fund primarily invests at all times in a Since Inception (%) 4.04 4.18 -0.14 sample of equities constituting the Index with such other securities as MPF shall deem it necessary Cumulative to capture the performance of the Index. Stock 3 Month (%) 11.54 11.51 0.04 index futures can be used for efficient portfolio 1 Year (%) 23.30 23.28 0.01 management. 3 Year (%) 14.95 15.24 -0.29 The following are excluded by the index provider from the index: Controversies (as defined by the ten 5 Year (%) 3.96 4.52 -0.56 principles of the UN Global Compact); Controversial Since Inception (%) 65.75 68.57 -2.81 weapons (including chemical & biological weapons, cluster munitions and anti-personnel landmines). Calendar 2021 (year to date) 9.74 9.71 0.03 Benchmark 2020 -1.28 -1.47 0.19 FTSE Developed Middle East and Africa ex 2019 10.82 11.07 -0.24 Controversies ex CW Index 2018 -0.47 -0.12 -0.35 Structure 2017 -10.77 -10.66 -0.12 Limited Company Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

The Banking System in Israel

CHAPTER XIV THE BANKING SYSTEM IN ISRAEL I. DEVELOPMENT OF THE BANKING SYSTEM Israel possesses a welldeveloped banking system, evidenced by the fact that bank deposits constitute some 60 per cent of the money supply. Apart from one or two banks founded in the period of the Ottoman Empire (such as, for example, the Bank Leumi LeTsrael B.M., formerly the AngloPalestine Bank Ltd.), most of the banks now functioning in Israel were established during the British Mandate. During this period, some dozens of banks were founded; but the economic crises which hit Palestine during the Abyssinian War and again at the outbreak of World War II, resulted in the liquidation of many of the smaller, and the strengthening of the more solid, institutions. The Banking Ordinance, 1921, which ifxed the legal basis of bank operations, was amended several times and the changes were eventually consolidated in the Banking Ordinance, 1941, which is still in force today. The Ordinance provided, inter alia, that no banking business might be conducted without a permit from the High Commissioner, that the minimum approved nominal capital of a bank be £P. 50,000, the minimum paidup capital be £P.25,000; and that all banks submit a monthly report to the Financial Secretary on their assets and liabilities. The Ordin ance also imposed on all banks the obligation to publish an annual balance sheet and a profit and loss account. The High Commissioner appointed a Controller of Banks and an Advisory Committee for Banking. With the creation of the State of Israel, the powers exercised by the High Commissioner under the Banking Ordinance were transferred to the Minister of Finance, and the control over banking activities was vested in the Department of Bank Control, a partofthe Ministryof Finance A new Advisory Committee for Bank ing was appointed by the Minister of Finance; its function was to consider problems relating to the activities of the banking system and to submit its recommendations to the Minister. -

Domestically Owned Versus Foreign-Owned Banks in Israel

Domestic bank intermediation: domestically owned versus foreign-owned banks in Israel David Marzuk1 1. The Israeli banking system – an overview A. The structure of the banking system and its scope of activity Israel has a highly developed banking system. At the end of June 2009, there were 23 banking corporations registered in Israel, including 14 commercial banks, two mortgage banks, two joint-service companies and five foreign banks. Despite the spate of financial deregulation in recent years, the Israeli banking sector still plays a key role in the country’s financial system and overall economy. It is also highly concentrated – the five main banking groups (Bank Hapoalim, Bank Leumi, First International Bank, Israel Discount Bank and Mizrahi-Tefahot Bank) together accounted for 94.3% of total assets as of June 2009. The two largest groups (Bank Leumi and Bank Hapoalim) accounted for almost 56.8% of total assets. The sector as a whole and the large banking groups in particular are organised around the concept of “universal” banking, in which commercial banks offer a full range of retail and corporate banking services. Those services include: mortgages, leasing and other forms of finance; brokerage in the local and foreign capital markets; underwriting and investment banking; and numerous specialised services. Furthermore, until the mid-1990s, the banking groups were deeply involved in non-financial activities. However, a law passed in 1996 forced the banks to divest their controlling stakes in non-financial companies and conglomerates (including insurance companies). This development was part of a privatisation process which was almost completed in 2005 (with the important exception of Bank Leumi). -

Delek Cover English 04.2006

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 Delek Group Ltd 7, Giborei Israel St., P.O.B 8464, Industrial Zone South, Netanya 42504, Israel Tel: 972 9 8638444, 972 9 8638555 Fax: 972 9 885495 www.delek-group.com Table of Contents: Chapter A Corporate Description Chapter B Director's Report on the Corporation Chapter C Financial Statements for December 31, 2004 Chapter D Additional Information on the Corporation Chapter E MATAV - CABLE SYSTEMS MEDIA LTD IMPORTANT This document is an unofficial translation from the Hebrew original of the 2005 annual report of Delek Group Ltd. that was submitted to the Tel-Aviv Stock Exchange and the Israeli Securities Authority on March 29, 2006. The Hebrew version submitted to the TASE and the Israeli Securities Authority shall be the sole binding version. Investors are urged to review the full Hebrew report. Part One – A Description of the General Development of the Company's Businesses 1. The Company's Activities and the Development of its Business ......................... 3 2. Sectors of Operation .................................................................................................. 6 3. Equity Investments in the Company and Transactions in its Shares................... 7 4. Dividend Distribution ................................................................................................. 8 5. Financial Information Regarding the Group's Sectors........................................... 9 6. The General Environment and Outside Influences................................................. 9 7. Oil Refining Sector -

Financial Statements

BANK LEUMI LE-ISRAEL B.M. AND ITS INVESTEE COMPANIES Annual Report 2009 Bank Leumi le-Israel B.M. Head Office: 34 Yehuda Halevi Street, Tel Aviv 65546, Israel The Bank has received the consent of the Supervisor of Banks to the publication of the annual financial report on a consolidated basis only, with condensed statements of the Bank (not consolidated) in Note 30 to the Financial Statements. The figures of the Bank alone are available on request from the offices of the Bank at 34 Yehuda Halevi Street, Tel Aviv or on its website: www.bankleumi.com. This is a translation from the Hebrew and has been prepared for convenience only. In the case of any discrepancy, the Hebrew will prevail. 1 2 Bank Leumi le-Israel B.M. and its Investee Companies Annual Report 2009 Index Page Directors' Report A. General Board of Directors 5 Management 7 B. General Developments in the Group's Business Description of the Leumi Group's Business Activities and their General Development 8 Business Strategy 14 Control of the Bank 17 Description of Operating Segments 21 Capital Resources and Transactions in the Shares of the Bank 26 Distribution of Dividends 33 Principal Data in the Last Five Years 34 C. Other Information Principal Developments in the Economy 35 General Environment and the Effect of External Factors on Activities 43 Legislation Affecting the Banking System 43 Accounting Policy on Critical Subjects 52 Disclosure on the Procedure for Approval of the Financial Statements 58 D. Description of the Group's Business according to Segments and Areas of Activity -

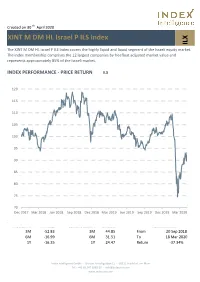

ILX XINT M DM HL Israel P ILS Index

Created on 30 th April 2020 XINT M DM HL Israel P ILS Index ILX The XINT M DM HL Israel P ILS Index covers the highly liquid and liquid segment of the Israeli equity market. The index membership comprises the 12 largest companies by freefloat adjusted market value and represents approximately 85% of the Israeli market. INDEX PERFORMANCE - PRICE RETURN ILX 120 115 110 105 100 95 90 85 80 75 70 Dec 2017 Mar 2018 Jun 2018 Sep 2018 Dec 2018 Mar 2019 Jun 2019 Sep 2019 Dec 2019 Mar 2020 Index Return % annualised Standard Deviation % annualised Maximum Drawdown 3M -52.83 3M 44.85 From 20 Sep 2018 6M -16.99 6M 31.51 To 18 Mar 2020 1Y -16.35 1Y 24.47 Return -37.34% Index Intelligence GmbH - Grosser Hirschgraben 15 - 60311 Frankfurt am Main Tel.: +49 69 247 5583 50 - [email protected] www.index-int.com TOP 10 Largest Constituents FFMV million Weight Industry Sector Check Point Software Technologies Ltd 17.07% 4,471,198 17.07% Technology Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd 15.55% 4,072,206 15.55% Health Care Nice Ltd 13.77% 3,605,623 13.77% Technology Bank Leumi Le Israel BM 10.57% 2,769,635 10.57% Banks Bank Hapoalim BM 9.74% 2,551,239 9.74% Banks Wix.com Ltd 8.43% 2,206,957 8.43% Technology Israel Discount Bank Ltd 5.05% 1,323,487 5.05% Banks CyberArk Software Ltd 4.94% 1,294,068 4.94% Technology Elbit Systems Ltd 4.40% 1,152,520 4.40% Industrial Goods & Services Mizrahi Tefahot Bank Ltd 3.86% 1,010,693 3.86% Banks Total 24,457,627 93.37% This information has been prepared by Index Intelligence GmbH (“IIG”). -

The Story of Israel As Told by Banknotes

M NEY talks The Story of Israel as told by Banknotes Educational Resource FOR ISRAEL EDUCATION Developed, compiled and written by: Vavi Toran Edited by: Rachel Dorsey Money Talks was created by Jewish LearningWorks in partnership with The iCenter for Israel Education This educational resource draws from many sources that were compiled and edited for the sole use of educators, for educational purposes only. FOR ISRAEL EDUCATION Introduction National Identity in Your Wallet “There is always a story in any national banknote. Printed on a white sheet of paper, there is a tale expressed by images and text, that makes the difference between white paper and paper money.” Sebastián Guerrini, 2011 We handle money nearly every day. But how much do we really know about our banknotes? Which president is on the $50 bill? Which banknote showcases the White House? Which one includes the Statue of Liberty torch? Why were the symbols chosen? What stories do they tell? Banknotes can be examined and deciphered to understand Like other commemoration the history and politics of any nation. Having changed eight agents, such as street times between its establishment and 2017, Israel’s banknotes names or coins, banknotes offer an especially interesting opportunity to explore the have symbolic and political history of the Jewish state. significance. The messages 2017 marks the eighth time that the State of Israel changed the design of its means of payment. Israel is considered expressed on the notes are innovative in this regard, as opposed to other countries in inserted on a daily basis, in the world that maintain uniform design over many years. -

Bezeq's IPVPN Networkb in All Bank Leumi Branches

Bezeq's IPVPN networkb in all bank Leumi branches October 9, 2005 Bezeq's IPVPN network in all bank Leumi branches In the past few days, the connection of about 250 branches of Bank Leumi to Bezeq's IPVPN and transmission networks was completed. This means that Bank Leumi provides an IPVPN network of Bezeq, secure and surviving broadband communications enabling the running of applications and transfer of content between the branches of the bank. The bank's customers are already enjoying faster and more efficient service. Broadband lines have been installed in the bank's main offices for full back-up of the computer centers, and transmission systems which are among the largest in the country have been set up. A Cisco router has been installed in every branch, and the optical infrastructure in most of the branches has been upgraded. The project, which lasted about a year, was implemented by employees from Bezeq's Engineering and Planning Division, Sales and Marketing Division and Bezeq Business Unit. The project will be extended to upgrade the entire communications array at Bank Leumi, positioning the bank as a leader in banking communications not only in Israel but worldwide. The successful completion of the project was marked by a festive ceremony attended by the heads of Bezeq and Bank Leumi. Rami Hazan, VP for Sales and Marketing, said that Bezeq's unique IPVPN service is proving to be a quality service in great demand, and since the beginning of 2004, 650 organizations and 30,000 lines have been connected. "Bezeq is the only one in Israel to offer nationwide IPVPN service, and therefore the only one who can provide organizations such as Bank Leumi with the service wherever it has a branch – be it Ofakim or Tel Aviv, the bank receives the same high quality service at all times." Hazan added that Bezeq has set up a dedicated support center for IPVPN customers, available 24/7, which is staffed by dozens of employees with computer communications qualifications and who specialize in IPVPN. -

Bluestar Israel Global Total Investable Market Index

FACTSHEET BlueStar Israel Global Total Investable Market Index The BlueStar Israel Global Total Investable Market Index (BITM) tracks all Israeli equities, across all sectors of the economy, irrespective of their listing venue. The definition of an Israeli company is based on MVIS's proprietary research-driven framework. BITM covers 100% of the investable universve. Key Features Size and Liquidity Requirements Full MCap of at least 150 mln USD.Three month average-daily-trading volume of at least 1 mln USD at a review and also at the previous two reviews.At least 250,000 shares traded per month over the last six months at a review and also at the previous two reviews. Pure-Play Index includes non-local companies. Diversification Company weightings are capped at 10%. Review All Time High/Low 52-Week High/Low Semiannual in June and December. Total Return Net Index 397.27/92.33 397.27/273.88 Index Data INDEX PARAMETERS FUNDAMENTALS* ANNUALISED PERFORMANCE* Launch Date 31 May 2016 Components 173.00 Price/Earnings Trailing 69.05 1 Month 1.67% Type Country Volatility (1 year) 18.82 Price/Book 2.32 1 Year 28.91% Currency USD Full MCap bn USD 0.32 Price/Sales 2.31 3 Years 12.38% Base Date 31 Dec 2008 Float MCap bn USD 0.32 Price/Cash Flow 11.14 5 Years 11.60% Base Value 100.00 Correlation* (1 year) 0.85 Dividend Yield 1.10 Since Inception 11.37% * as of 31 Jul 2021 * MSCI Daily TR Gross Israel USD * Total Return Net Index Country and Size Weightings COUNTRY WEIGHTINGS EXCL. -

Creatingvalue in a Changing World

CREATINGVALUE IN A CHANGING WORLD 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT US FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Founded in 2001, Delek US Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: DK) SEGMENT CONTRIBUTION MARGIN is a diversified energy company with assets in the IN MILLIONS petroleum refining, logistics and retail industries. Delek US consists of three business segments: $37.2 $45.2 REFINING, LOGISTICS and RETAIL. LOGISTICS RETAIL Refining Segment $586.1 REFINING $30.4 Delek US’ subsidiaries own and operate refineries in Tyler, Texas, $45.2 and El Dorado, Arkansas, with a combined nameplate production capacity of 140,000 barrels per day. Tyler is a 60,000-barrel-per- day inland refinery that processes primarily local sweet crude $379.6 oils and manufactures mostly light, high-value, refined products, such as gasoline and distillate fuel. Tyler primarily serves a niche $24.8 market in east Texas. El Dorado is an 80,000-barrel-per-day $52.4 inland, mid-continent refinery that has the flexibility to process a combination of local, Mid-Continent, Gulf Coast and rail-supplied crudes. El Dorado manufactures a combination of light products, $62.4 in addition to a slate of industrial products, including asphalt. 2010 2011 2012 Logistics Segment HSD 5-3-2 GULF COAST CRACK SPREAD PER BARREL Delek US beneficially owns 62.4 percent (including the 2 percent general partner interest) of Delek Logistics Partners, LP. (NYSE: DKL). Delek Logistics Partners is a growth-oriented master limited partnership focused on owning and operating midstream energy infrastructure assets. On November 7, 2012, Delek Logistics completed its initial public offering, which includes certain assets formerly in the Delek US marketing segment, and pipeline and $17.54 $23.14 $30.80 $20.34 $23.87 $25.42 $29.96 $26.71 related tankage assets previously in the Delek US refining segment. -

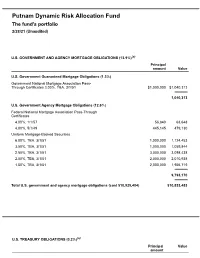

Dynamic Risk Allocation Fund Q3 Portfolio Holdings

Putnam Dynamic Risk Allocation Fund The fund's portfolio 2/28/21 (Unaudited) U.S. GOVERNMENT AND AGENCY MORTGAGE OBLIGATIONS (13.9%)(a) Principal amount Value U.S. Government Guaranteed Mortgage Obligations (1.3%) Government National Mortgage Association Pass- Through Certificates 3.00%, TBA, 3/1/51 $1,000,000 $1,040,313 1,040,313 U.S. Government Agency Mortgage Obligations (12.6%) Federal National Mortgage Association Pass-Through Certificates 4.00%, 1/1/57 56,840 63,648 4.00%, 5/1/49 445,145 479,130 Uniform Mortgage-Backed Securities 6.00%, TBA, 3/1/51 1,000,000 1,124,453 3.50%, TBA, 3/1/51 1,000,000 1,059,844 2.50%, TBA, 3/1/51 3,000,000 3,098,438 2.00%, TBA, 3/1/51 2,000,000 2,010,938 1.50%, TBA, 3/1/51 2,000,000 1,956,719 9,793,170 Total U.S. government and agency mortgage obligations (cost $10,925,404) $10,833,483 U.S. TREASURY OBLIGATIONS (0.2%)(a) Principal Value amount U.S. Treasury Notes 2.00%, 4/30/24(i) $116,000 $122,910 Total U.S. treasury obligations (cost $122,910) $122,910 COMMON STOCKS (11.8%)(a) Shares Value Basic materials (1.3%) Anglo American PLC (United Kingdom) 2,799 $107,695 BHP Billiton, Ltd. (Australia) 438 16,558 BHP Group PLC (United Kingdom) 2,150 67,954 Compagnie De Saint-Gobain (France)(NON) 1,992 106,724 Covestro AG (Germany) 1,509 109,200 CRH PLC (Ireland) 1,562 67,483 Eiffage SA (France)(NON) 425 43,652 Fortescue Metals Group, Ltd.