A Twist on the Traditional Challah Bread

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

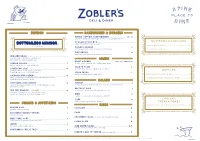

Challah French Toast Buttermilk Pancakes Waffles

ROAST CHICKEN ................................................................HALF 14 / WHOLE 26 20 DEVILED EGGS ...........................................................................................3 challah, apple, onion & sage with gravy for two hours paprika, shallot crackling SPICY HONEY FRIED CHICKEN ...................................................................16 LATKES sesame seeds & coriander sour cream & apple sauce ................................................................................5 SALMON FILLET .......................................................................................................17 ..............................................................7 PASTRAMI & CHEESE FRIES shaved fennel, marcona almonds & green olives STEAK FRITES �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 9oz rib-eye with bearnaise (add egg 1) BUTTERMILK PANCAKES AVOCADO BAGEL ......................................................................................7 crushed avocado with chili & lemon, red onion, radishes & blueberry compote.............................................8 CAESAR ....................................................................................................... 9 buttermilk dressing on poppy bagel baby gem, grana, challah croutons & anchovies (add chicken 4) maple, butter & bacon.......................................9 BODEGA CLASSIC .....................................................................................................8 bacon, -

April 26Th, 2015 Savory

THE OFFICIAL BETH EL KUGEL COOK- OFF RECIPE BOOK April 26th, 2015 Savory Challah-Peño Continued Cheddar Kugel Prepare the bread crumbs by pulsing the bread in the food processor fitted with a metal Chef: Kathy Sklar blade. Keep it chunky; you do not want fine crumbs. You should have at least 1 cup. Add FOR THE KUGEL the jalapeños, butter, eggs, cheddar cheese, 1 pound egg noodles cottage cheese, sour cream, and nutmeg to the noodles. Mix well and season to taste with 1-2 jalapeño peppers salt and pepper. Pour contents into a greased 13 x 9 inch pan. Melt butter in small frying 4 tbsp. butter, melted pan. Mix in the bread crumbs. Sprinkle on top 2 eggs of the kugel. Bake at 350 degrees for 40 minutes until top is golden and crusty. 2 cups grated cheddar cheese 2 cups cottage cheese ¼ cup sour cream ¼ tsp. nutmeg Salt and pepper to taste Corn Kugel FOR THE TOPPING Chef: Glenda Koby Last week’s challah bread (to make bread crumbs) Ingredients: 2 cans creamed corn 1 tbsp. butter 3 eggs 1/2 stick margarine Cook the noodles according to package 1 tsp. vanilla directions, rinse under cold water and transfer 1/4 cup matzo meal to a large mixing bowl. 1 tsp. salt Roast the jalapeno pepper by holding it with a 2 tbsp. sugar fork or tongs over the open flame of a gas burner until blackened all over, turning Melt margarine. Add corn. Beat eggs until frequently. Transfer the blackened jalapeno to fluffy and add to mixture with other a plastic bag, seal the bag and steam for 30 ingredients. -

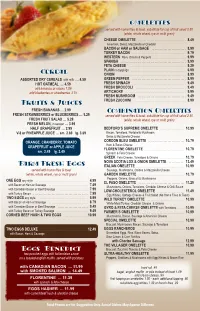

Printer Friendly Menu

omelettes served with home fries & toast, substitute for cup of fruit salad 2.50 (white, whole wheat, rye or multi grain) CHEESE OMELETTE ..................................... 8.49 American, Swiss, Mozzarella or Cheddar BACON or HAM or SAUSAGE .......................... 8.99 TURKEY BACON ......................................... 9.79 WESTERN Ham, Onions & Peppers .......................... 9.99 SPANISH .................................................. 9.99 FETA CHEESE ........................................... 9.29 Cereal PLAIN no toppings .......................................... 6.99 ONION .................................................... 8.99 ASSORTED DRY CEREALS with milk … 4.59 GREEN PEPPER ......................................... 8.99 HOT OATMEAL … 4.59 FRESH SPINACH ........................................ 9.49 add bananas or raisins 1.59 FRESH BROCCOLI ...................................... 9.49 add blueberries or strawberries 3.79 ARTICHOKE .............................................. 9.99 FRESH MUSHROOM ..................................... 9.49 Fruits & Juices FRESH ZUCCHINI ........................................ 8.99 FRESH BANANAS … 2.99 Combination Omelettes FRESH STRAWBERRIES or BLUEBERRIES … 5.29 served with home fries & toast, substitute for cup of fruit salad 2.50 FRESH FRUIT SALAD … 5.29 (white, whole wheat, rye or multi grain) FRESH MELON, in season … 3.99 HALF GRAPEFRUIT … 2.99 BEDFORD’S SUPREME OMELETTE ................... 10.99 V-8 or PINEAPPLE JUICE … sm. 2.69 lg. 3.69 Bacon, Tomatoes, Portobello Mushroom, -

Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin

Cultures in Transit Diaspora Identities: Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin DEVORAH ROMANEK This essay investigates how material culture acts as an agent of cultural construction when social and cultural practices are geographically displaced. It does this by taking a comparative look at current Jewish Diaspora communities in London and Berlin, and by analyzing the production, consumption and broader meaning of three Jewish baked goods – matzos, challah and bagels - in the context of Diaspora communities in these two cities. The comparison between London and Berlin also allows a consideration of the construction of ‘locality’/‘setting’, particularly in the transient sense of a fluid concept of sense-of-place as constructed against a backdrop of material culture; additionally, the level of religious observance; the contrast of notions of ‘fixed’ and ‘fluid’, and ‘traditional’ and ‘cosmopolitan’; and the agency of the baked goods themselves is observed and analyzed. Introduction Anthropological discussions on the theme of cultures in movement, that is to say Diaspora, or the more contemporary notions of globalization and transnationalism, offer many disparate theories. There is the argument that globalization as a post- modern phenomenon is bringing an end to the practice of ‘tradition’ and ‘traditional cultures’, and that it is inviting a worldwide culture of heterogeneity .1 1 For a discussion of this see Anthony Giddens, “Living in a post-traditional society”, in Ulrich Beck, Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1994. Diaspora Identities: Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin There is the counter-argument that the pressure or threat (perceived or real) felt by various communities and cultures against their ‘traditional’ ways has induced a counter-reaction, which is being expressed in renewed and intensified forms of nationalism, and increasingly more delineated and defined concepts of self and community. -

Passover Desserts Sale! Page 11

April 2016 Volume 55 - Number 4 Adar II - Nissan 5776 page 12 Early Bird Pricing Ends April 6 at 5:00 pm Passover Desserts Sale! page 11 Miriam’s Tea page 8 Meitin Religious School Open House page 10 Building Community Since 1954 Staff From Our Rabbi Rabbi.................................... Joshua Neely By Rabbi Joshua Neely Cong. Life Coord. ...... Susan Bernstein Youth Advisor ......................... Lisa Hart Off. Admin.... John-Patrick Alexander Bookkeeper .................... Patricia Young artin Buber recorded a Hasidic tale of two disci- M ples who were visiting a different rabbi in an- Executive other town. It happened to be the evening service where we Committee say the blessing upon seeing the new moon for the first time in the month. President .............................. Mark Kluger The local rabbi did the blessing differently than their rabbi always did and 1st Vice President.. .......... Sharon Sachs they were quite shocked. Perhaps he is not such a sage, they thought, and VP Membership ............ Geanne Share VP Education ........................ Kris Crane turned to head home without waiting to learn together with him or his com- Comptroller .................... Michelle Bilsky munity. The rabbi sensed their trouble and approached them. Is our God so Secretary ............................ Mollie Savage small that there is only one narrow way to serve, he asked? The students Sisterhood Rep. .......... Cathy Swerdlow Men’s Club Co-Pres.. ................................ stayed and learned much. The rabbi wasn’t saying anything goes, but often we ................. Wayne Bilsky & Steven Sesit believe that every detail of what we do or believe is absolutely essential and Past President. ................ Eric Hoffman incontrovertible. We fight with rancor or disgust with those who disagree with our approach. -

![Філологічні Трактати. – Том 5, № 4 '2013 17 Удк [811.161.1+811.411.16]:158.953.32:801.614](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0371/5-4-2013-17-811-161-1-811-411-16-158-953-32-801-614-1060371.webp)

Філологічні Трактати. – Том 5, № 4 '2013 17 Удк [811.161.1+811.411.16]:158.953.32:801.614

УДК [811.161.1+811.411.16]:158.953.32:801.614 МУЗЫКАЛЬНЫЕ ГЕШТАЛЬТЫ КОНЦЕПТА SCHTETL/SHTETL Л. И. Дегтярева, Сумский государственный университет, ул. Римского-Корсакова, 2, г. Сумы, 40007, Украина В статье исследуются музыкальные образы-гештальты концепта schtetl/shtetl в русском, немецком языках и идиш, основанные на данных словарей, энциклопедий и справочников. Устанавливаются ассоциативные связи музыкальной и лингвокультурологической памяти. Анализируются ментальный лексикон, логические отношения между гештальтами концепта и фамилии. Ключевые слова: музыкальный гештальт, штетл, местечко, концепт, эйдетическая память. Оyfn veg shteyt a boym, shteyt er arayngeboygn, ale feygl funem boym zanen sikh tserfloygn. Dray ken mayrev, dray ken misrekh, un der resht ken dorem, un dem boym gelozt aleyn hefker far dem shturem. – У дороги, над ручьём, дерево в печали – птицы, что гнездились в нём, все давно умчали, кто на запад и восток, кто подался к югу, кров их снова одинок, ожидает вьюгу (1). Актуальность выбранной темы связана с уникальностью способов постижения мира каждой языковой личности, включающей следующие компоненты: 1) мировоззренческий – систему ценностей или жизненных смыслов; 2) культурологический – уровень освоения культуры; 3) личностный – индивидуальное, глубинное, что есть в каждом человеке, 4) музыкальный, т. е. эмоционально-чувственный. По мере развития мотивационно-потребностной сферы человека может изменяться его отношение к своему прошлому, вследствие чего одно и то же знание может по-разному храниться в памяти человека. Человеческая память ассоциативна, то есть некоторое воспоминание может порождать большую связанную с ним область, когда один предмет напоминает нам о другом по цепочке умственных ассоциаций. Всего лишь несколько музыкальных тактов, несколько строчек из старых песен могут вызвать целую гамму чувственных воспоминаний, включая пейзажи, звуки и запахи. -

Garden of Palms Dining | Menu Subject to Change | Lic#197609826 | Supervised Under the Rabbinical Council of California (RCC)

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday BREAKFAST 1 BREAKFAST 2 BREAKFAST 3 BREAKFAST 4 BREAKFAST 5 BREAKFAST 6 BREAKFAST 7 Pancakes, Eggs Any Style, French Toast, Eggs Any Style, Waes, Eggs Any Style, Pancakes, Eggs Any Style, French Toast, Eggs any Style, Waes, Eggs Any Style, Lox & Bagel, Cream Cheese, Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hot & Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit Hard Boiled Egg, Cold Cereal, Fresh Fruit LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Lunch Tomato Basil Soup Barley Soup Cream of Butternut Squash Garden Vegetable Cabbage Celery Soup, Baked Fish Garden Vegetable Soup Borscht Grilled Cheese Sandwich Mushroom Quiche/ Roll Vegetable Pizza, Garden Salad Cheese & Blueberry Blintz, Small Salad Roasted Potatoes, Potato Latkes, Sour Cream/Apple Tuna Salad/Egg Salad French Fries/Side Salad Marinated Beet- Onion Salad Orange Mun & Fresh Fruit Apple Sauce/ Sour Cream Marinated Three Bean Salad Sauce, Chef's Salad, Blended Vegetable Carrot Raisin Slaw, Beet & Onion Assorted Ice Cream Fresh Fruit DINNER DINNER Fresh Fruit DINNER Lemon Cake DINNER DINNER Onion Soup Sausage Lentil Soup DINNER Matzo Ball Soup DINNER Minestrone Soup White Bean Soup Baked Salmon Chicken Teriyaki Chef's soup Potato Kugel Vegetable Soup, Braised Beef Brisket, Mashed Chicken Cacciatore Steamed Couscous Egg Noodles Stuffed Cabbage Gelte Fish Baked Chicken with Potatoes Potatoes with Steamed Vegetables Blended Vegetables with Rice -

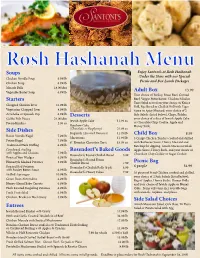

Rosh Hashanah Menu

Rosh Hashanah Menu Soups Enjoy Santoni’s at Rosh Hashanah Under the Stars with our Special Chicken Noodle Soup 6.99/lb Picnic and Box Lunch Packages Chicken Soup 6.99/lb Matzoh Balls 18.00/doz 13.99 Vegetable Barley Soup 6.99/lb Adult Box Your choice of Turkey, Roast Beef, Corned Starters Beef, Veggie Powerhouse, Chicken Salad or Tuna Salad served on your choice of Kaiser Chopped Chicken Liver 14.99/lb Roll, Rye Bread or Challah Roll with Tiger Vegetarian Chopped Liver 8.99/lb Sauce or Spicy Mustard, your choice of 2 Artichoke or Spinach Dip 6.99/lb Desserts Side Salads (listed below), Chips, Pickles, Gefilte Fish Pieces 24.00/doz your choice of a slice of Jewish Apple Cake Jewish Apple Cake 11.99 ea Potato Knishes 2.50 ea or Chocolate Chip Cookie, Apple and Rainbow Cake Honey Stick. Side Dishes (Chocolate or Raspberry) 21.99 ea Rugalach (Assorted Varieties) 11.99/lb 8.99 Raisin Noodle Kugel 7.99/lb Child Box Macaroons 11.99/lb 3 Crispy Chicken Tenders cooked and chilled Potato Kugel 7.99/lb 8” Flourless Chocolate Torte 19.99 ea with Barbecue Sauce, Honey Mustard and Traditional Herb Stuffing 6.99/lb Ketchup for dipping, Amish Macaroni Salad, Cornbread Stuffing Rosendorf’s Baked Goods Apple Sauce, Honey Stick, and your choice of with Apples and Craisins 7.99/lb Rosendorfs Round Challah Bread 6.99 Chocolate Chip Cookie or Sugar Cookie. Roasted Yam Wedges 6.99/lb Rosendorf’s Round Raisin Homestyle Mashed Potatoes 5.99/lb Challah Bread 7.99 Picnic Bag Roasted Red Potatoes Rosendorf’s Challah Rolls (6 pk) 6.99 6 people 54.99 with Parsley Butter Sauce 6.99/lb Rosendorf’s Honey Cakes 7.99 16 pieces of Fried Chicken cooked and chilled, Grilled Asparagus 10.99/lb your choice of 2 Side Salads (listed below), Green Bean Almondine 6.99/lb Bag of Apples, Honey Sticks, Dinner Rolls, Honey Glazed Baby Carrots 6.99/lb and your choice of Jewish Apple or Honey Herb Roasted Fingerling Potatoes 6.99/lb Cake. -

BUBBIE's BRISKET & BAKERY Jewish Food Extravaganza!

BUBBIE’S BRISKET & BAKERY Jewish Food Extravaganza! Beth Shalom Synagogue 5827 N. Trenholm Road, Columbia, SC 29206 (803) 782-2500 www.Facebook.com/BubbiesBrisket/ Sunday, November 12, 2017 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Traditional Jewish Foods and Baked Goods All Food Purchases Are À la Carte Brisket Falafel Pickles Corned Beef Israeli Salad Rugalach Sandwiches Tzimmes Mandel Bread Stuffed Cabbage Kasha Varnishkes Cakes and more! Matzah Ball Soup Baba Ganoush Sweet & Sour Challah Meatballs Kid’s Meals Bubbie’s À la Carte Pre -Order Form 2017 www.Facebook.com/BubbiesBrisket www.BethShalomColumbia.org/Bubbies -Brisket-Bakery/ Item Price Qty Subtotal Brisket $22/lb Challah Loaf $8 Corned Beef $22/lb Mandel Bread (loaf) $10 Meatballs (3 - sweet & sour) $10 Rugelach (1 dozen) $12 Stuffed Cabbage (6 - sweet & sour) $18 Check# Date: GRAND TOTAL $ Name:__________________________________ Phone:__________________________________ Email:__________________________________ All items are kosher, packaged and frozen. The deadline for pre-orders is October 18th No pre-orders will be accepted after the deadline. All pre-orders must be accompanied with payment. Pre-orders may be picked up: Sunday, October 29th: 10 am - 12:30 pm or Wednesday, November 1st: 4:30 - 6 pm Pre-orders greater than $36.00 will receive a free tote. Orders can be placed by: Calling the synagogue at (803) 782-2500 Dropping off form at the office Through a link on our weekly e-newsletter or Facebook page Bubbie’s Brisket & Bakery As members of the Sponsorship Committee of Bubbie's Brisket & Bakery - Jewish Food Extravaganza, we are proud to announce Bubbie's (aka as a Jewish grandmother) 9th annual event on Sunday, November 12, 2017 from 11am – 3pm at Beth Shalom Synagogue, 5827 N. -

Challah Explanations

The Meaning Behind the Ingredients Each ingredient has tremendous significance. By understanding the significance, you can focus on the essence and blessing of each ingredient while adding it to the mixture. As you pour each ingredient, have in mind that this is for the merit of Shabbat. THE BOWL represents your home. Each ingredient added to dough, we pray for life, children, and anything going on in our your bowl should bring its unique blessing. lives that we want G-d to reveal to us. FLOUR represents sustenance, not only our livelihood, but also The last step in making the dough is to take all of these our relationships with others. We pray that G-d should bless us essential ingredients that bring their own important blessings, with a livelihood that we should use for the right reasons, and and unify them. We think about the oneness of G-d and the that He helps us sustain the relationships that might need oneness of the Jewish People; and as we knead the dough, some assistance, and thank Him for the relationships we have this is a special time to pray for anything you need, as well as that sustain us. the needs of your family, friends, and the world. SUGAR represents the sweetness and good in our lives. Sugar SEPARATE THE CHALLAH also represents emunah (faith). When we have proper faith, then everything becomes sweet. Even the challenges in our Conditions that allow you to perform the separation of the challah: lives we realise are all from G-d and all for the best. -

Madison Jewish News 4

April 2017 Nisan 5777 A Publication of the Jewish Federation of Madison INSIDE THIS ISSUE Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 Lots of Fun at the Purim Carnival ....................14-15 Jewish Social Services....................................21-23 Simchas & Condolences ........................................6 Jewish Education ..........................................18-19 Israel & The World ........................................24-25 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............20 Camp Corner ....................................................27 My Life with Sir Nicholas Winton Renata Laxova, Professor Emerita at Force. Holocaust. the UW-Madison participated in a two- For the remainder of I happened to be one day celebration in memory of Sir his life, however, a single of the children from Nicholas Winton. Sir Nicholas, who died event forever occupied Nicky’s last Kindertrans- in 2015, organized eight Kindertrans- his mind. Having suc- port to arrive in Britain ports from Czechoslovakia in 1939, sav- cessfully organized the safely, (among only five ing the lives of hundreds of Jewish Czech safe arrival in London of with two surviving par- children, Dr. Laxova among them. Here eight Kindertransports, ents). It is my strong con- are some of her recollections, inspired totaling 669 children, he viction that not only I, but by the recent event. had arranged another— also both my parents, the ninth and largest owed our lives to Sir Save the Date BY DR. RENATA LAXOVA train, carrying 250 chil- Nicholas. My inclusion in dren—which was wait- the transport enabled my for Interfaith ing, prepared for parents to agree to sepa- I never actually met or spoke with departure, at the Prague Dr. Renata Laxova rate and hide, without him and our only direct contact lasted main railway station on having to worry about Advocacy Day! some thirty seconds out of his one hun- September 1, 1939, the day that Hitler me, their only child. -

Challah French Toast Buttermilk Pancakes Waffles

SINGLE / DOUBLE CHEESEBURGER .............................................. 12 / 14 all beef cheeseburger (add egg 1, add bacon 1.5, add pastrami 2.5) 37 ESSEX ST HOT DOG ....................................................................................... 9 BUTTERMILK PANCAKES 20 all beef frankfurter with ‘the works’ for two hours maple, butter, bacon.............................................9 ZOBLER’S REUBEN ................................................................................................11 corned beef, kraut, swiss & russian on toasted rye blueberries compote.............................................8 THE CLASSIC ............................................................................................................ 12 pastrami, coleslaw, swiss & russian on toasted rye AVOCADO BAGEL ......................................................................................7 avocado, lemon. red onion, radishes and buttermilk dressing on poppy bagel ROAST CHICKEN ............................................................. HALF 13 / WHOLE 24 BODEGA CLASSIC .....................................................................................................7 challah, apple, onion & sage stuffing with gravy bacon, egg & cheese on a challah roll SALMON FILLET .......................................................................................................16 LOWER EAST SIDE ..................................................................................................10 shaved fennel, marcona almonds, green