Downloaded 2021-10-02T14:17:14Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Aaron Mumford Boehlert Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Boehlert, Aaron Mumford, "Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 136. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/136 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hitler’s Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Senior Project submitted to the Division of Arts of Bard College By Aaron Boehlert Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 2017 A. Boehlert 2 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the infinite patience, support, and guidance of my advisor, Olga Touloumi, truly a force to be reckoned with in the best possible way. We’ve had laughs, fights, and some of the most incredible moments of collaboration, and I can’t imagine having spent this year working with anyone else. -

Phase One at the Dyeworks Phase One at the Dyeworks

PHASE ONE AT THE DYEWORKS PHASE ONE AT THE DYEWORKS External example - The Factory PAGE 3 INTRO 4 LUXURY LIVING 6 SPECIFICATIONS 22 INVESTMENT 29 FORSHAW 42 CONTACT 44 PHASE ONE AT THE DYEWORKS Example External - The Factory PAGE 5 THE FACTORY AT THE DYEWORKS Located in the city of Salford by the River Irwell, The Factory at The Dye Works is a brand new residential development which contains 232 stunning apartments spread across three buildings up to nine storeys. The images provided in this document are intended as a guide and could be subject to change. PHASE ONE AT THE DYEWORKS The Factory includes a range of luxury one, two and three bedroom apartments as well as two and three bedroom duplexes which are designed to the highest standard to provide residents with luxury living. All apartments will be fully furnished with high quality fixtures and fittings, and will feature a spacious living room as well LUXURY as a contemporary German engineered kitchen. To complement the rental experience, Dye Works offer a range of on-site amenities, gymnasium, communal lounges that provide adaptable space, be it for watching movies, gaming or social gatherings and rooftop gardens to enjoy private LIVING outside space. All in addition to the excellent range of shops, bars and restaurants which can be found in the local area accessible on foot, public transport or cycling, with on-site cycle storage provided. Residents can easily access Manchester city centre and Salford Quays/Media City as both are within walking distance and also well connected with frequent bus services throughout the day. -

Preservation Special Edition

PRESERVATION SPECIAL EDITION ISSUE 35 BROADSHEET Magazine of the Scottish Council on Archives WELCOME number 35 Welcome to the conservation and preservation issue of Broadsheet. You will see that many of the pieces touch on the impact of calamitous disasters not only on collections of objects, but also on the communities affected by the shock and loss that fire and floods leave in their wake. Disaster is never a welcome guest. Nonetheless, the better prepared we are if and when it strikes, the greater chance we have to safeguard both people and collections. At the SCA ‘Fire in the Archives’ event in September, speakers from the National Library of Wales and The Glasgow School of Art showed us that if there is a COVER IMAGE positive to be retrieved from disaster, it is in the valuable lessons we Johannes Regiomontanus: Calendar can learn from those that have been through it. (printed in Venice by Erhard Ratdolt, 9 August 1482). Featuring an instrument As the Convener of the Scottish Council on Archives Preservation with two moveable volvelles showing the Committee, I’m encouraging all archive services in Scotland to motion of the moon. University of complete our online Conservation and Preservation survey. The Glasgow Special Collections Scottish Council on Archives Preservation Committee aims to take a strategic approach to identify priority areas for action relating to the www.scottisharchives.org.uk/uogspeccol preservation and conservation of Scotland’s archive collections and of course, the associated access issues. Disaster preparedness is CONTRIBUTORS integral however, we want to hear more from you about what the Linda Ramsay, Yoko Shiraiwa, Ruth overall preservation priorities and challenges are for your service. -

Romanian-German Relations Before and During the Holocaust

ROMANIAN-GERMAN RELATIONS BEFORE AND DURING THE HOLOCAUST Introduction It was a paradox of the Second World War that Ion Antonescu, well known to be pro- Occidental, sided with Germany and led Romania in the war against the Allies. Yet, Romania’s alliance with Germany occurred against the background of the gradually eroding international order established at the end of World War I. Other contextual factors included the re-emergence of Germany as a great power after the rise of the National Socialist government and the growing involvement of the Soviet Union in European international relations. In East Central Europe, the years following the First World War were marked by a rise in nationalism characterized by strained relations between the new nation-states and their ethnic minorities.1 At the same time, France and England were increasingly reluctant to commit force to uphold the terms of the Versailles Treaty, and the Comintern began to view ethnic minorities as potential tools in the “anti-imperialist struggle.”2 In 1920, Romania had no disputes with Germany, while its eastern border was not recognized by the Soviet Union. Romanian-German Relations during the Interwar Period In the early twenties, relations between Romania and Germany were dominated by two issues: the reestablishment of bilateral trade and German reparations for war damages incurred during the World War I German occupation. The German side was mainly interested in trade, whereas the Romanian side wanted first to resolve the conflict over reparations. A settlement was reached only in 1928. The Berlin government acted very cautiously at that time. -

Sunday, April 1 Using This Devotional –Easter Sunday– –Four Simple Steps–

SUNDAY, APRIL 1 USING THIS DEVOTIONAL –EASTER SUNDAY– –FOUR SIMPLE STEPS– 1. CENTER YOURSELF Sit quietly for 30 seconds or so to calm your mind and settle your spirit. Take a few deep breaths and get comfortable. 2. READ THE QUOTED VERSE(S) Each day’s reflection begins with a few lines of scripture. Take a moment to read the passage through once or twice. If you feel so inclined you may want to find the passage in your Bible and read the surrounding lines to see it in its larger context. 3. READ THE REFLECTION As you read the day’s reflection, ask yourself, “How do these words connect with my life?” 4. PRAY To end your quiet time, say a short prayer either aloud or to yourself. by Steve Erspamer WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 14 SATURDAY, MARCH 31 –ASH WEDNESDAY– –HOLY SATURDAY– Matthew 4:17 Genesis 28:10-17 From that time Jesus began to proclaim, And he (Jacob) dreamed that there was a ladder set up “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.” on the earth, the top of it reaching to heaven; and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. Having handed out thousands of them with the Outdoor Church over the years, I like to think I know a thing or two about sandwiches. Should you one day make it to Jerusalem, you will no doubt also make your way to what many consider the holiest site in the world: the Here’s my biggest insight so far: order is everything. Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which they say is on the site of both Jesus' In case you were wondering, a sandwich with optimal flavor and crucifixion and of the tomb from which he was resurrected. -

Download Yam

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic jun2009 the age of stupid and the future of film distribution kiss in lima!!! stick out your tongue with a rojo report. in this yam we review // star trek, x-men origins: wolverine, terminator salvation, the brothers bloom, up, the sounds, shiina ringo, green day, life on mars, house m.d., portugirl and more // asian invasions in music, in films, the asian entertainment industry is coming to america// film Number four is really an unlucky the age of stupid pg2 x-men origins: wolverine pg4 number. I had nothing on my cover. This might seem like a very terminator salvation pg5 Nothing!! Moreover, a lot of people mainstream edition, but I managed star trek pg6 the brothers bloom pg7 either completely backed out to sneak something here and there. short films pg8 (notice the lack of names in the up pg9 the year of the asian pg10 contribution area) or took forever I encourage you to send me your coming soon pg13 to send in their stuff, and I even had thoughts and contributions to lost my own way. [email protected] music kiss me... kiss pg14 the sounds - crossing the rubicon pg15 Only Rojo seemed interested in amywong // shiina ringo - ariamaru tomi single pg15 green day - 21st century breakdown pg16 making herself a name on this issue, ss501 - u r man pg16 but maybe that's because she was p.s.: nate, your client really sucks. shinee - romeo pg17 snds - gee pg17 high on weed. She really should 2pm - time for change pg17 write more stuff (and watch better tv movies), but stop the weed-writing life on mars pg18 since it makes it almost house m.d. -

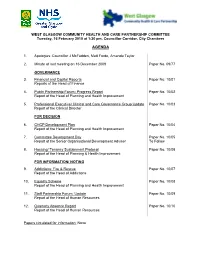

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Area

WEST GLASGOW COMMUNITY HEALTH AND CARE PARTNERSHIP COMMITTEE Tuesday, 16 February 2010 at 1:30 pm, Councillor Corridor, City Chambers AGENDA 1. Apologies: Councillor J McFadden, Matt Forde, Amanda Taylor 2. Minute of last meeting on 16 December 2009 Paper No. 09/77 GOVERNANCE 3. Financial and Capital Reports Paper No. 10/01 Reports of the Head of Finance 4. Public Partnership Forum: Progress Report Paper No. 10/02 Report of the Head of Planning and Health Improvement 5. Professional Executive/ Clinical and Care Governance Group Update Paper No. 10/03 Report of the Clinical Director FOR DECISION 6. CHCP Development Plan Paper No. 10/04 Report of the Head of Planning and Health Improvement 7. Committee Development Day Paper No. 10/05 Report of the Senior Organisational Development Adviser To Follow 8. Housing/ Tenancy Sustainment Protocol Paper No. 10/06 Report of the Head of Planning & Health Improvement FOR INFORMATION/ NOTING 9. Addictions: Fire & Rescue Paper No. 10/07 Report of the Head of Addictions 10. Equality Scheme Paper No. 10/08 Report of the Head of Planning and Health Improvement 11. Staff Partnership Forum: Update Paper No. 10/09 Report of the Head of Human Resources 12. Quarterly Absence Report Paper No. 10/10 Report of the Head of Human Resources Papers circulated for information: None GCHCPC(West)(M) 12/09 Paper No. 09/77 Minutes 6 GREATER GLASGOW NHS BOARD West Glasgow Community Health Care Partnership (CHCP) Committee Minutes of the Meeting held at 1.30pm on Tuesday, 15 December 2009 in the Councillors’ Corridor, City -

Councils Through Their Support Behind Clean Air Day with 2 Months to Go

Councils through their support behind Clean Air Day with 2 months to go PLANS are gathering pace for Scotland’s second Clean Air Day with all local authorities throwing their weight behind the event on Thursday June 21. Environmental Protection Scotland (EPS), which is co-ordinating the event, on behalf of the Scottish Government, working with UK organisers Global Action Plan, has been working closely with the 32 councils in recent weeks. Many are ready to download specialist toolkits which provide a plan for how to take part from the Scotland section of the Clean Air Day website. These are currently being updated and will be on the site shortly. The enthusiasm shown by the local authorities and other organisations has inspired the EPS team even further to make a success of this year’s event. Scotland’s biggest local authority, Glasgow, plans to stage a display of electric vehicles on Clean Air Day, where the public will be able to find out more about how affordable they can be, in the city’s George Square, as it gears up to introduce the country’s first Low Emission Zone in December 2018. Home Energy Scotland is involved in arranging vehicles and electric bicycles to encourage people to try them out in what promises to be a fun event while there’s been interest from private companies in providing vehicles – such as electric taxis – too. Edinburgh and Dundee are also pressing ahead with their own plans and Aberdeen has also expressed enthusiasm for Clean Air Day, which will see emphasis what individuals can do to improve air quality by taking part in active travel (such as cycling, walking to work or school or using public transport) and for motorists to consider switching to an electric vehicle to cut down on pollution from diesel or petrol engine vehicles. -

Implementation Plans from Amsterdam/Zaanstad, Berlin, Paris, Stockholm, Vienna, Warsaw and Zagreb

Implementation plans from Amsterdam/Zaanstad, Berlin, Paris, Stockholm, Vienna, Warsaw and Zagreb Synthesis report of Work Package 4 “Innovative governance solutions for integrative urban energy planning” (Deliverable 4.3) November 2017 This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 649883. URBAN LEARNING P R O J E C T P A R T N E R S . TINA VIENNA GMBH (COORDINATOR) . AGENCE PARISIENNE DU CLIMAT ASSOCIATION . GEMEENTE AMSTERDAM . BERLINER ENERGIEAGENTUR GMBH . ENERGETSKI INSTITUT HRVOJE POZAR . VILLE DE PARIS . STOCKHOLMS STAD . MIASTO STOŁECZNE WARSZAWA . MAGISTRAT DER STADT WIEN . GEMEENTE ZAANSTAD . GRAD ZAGREB Main author: Herbert Hemis (MA 20 – Department for energy planning, City of Vienna) Review: Ute Gigler (Energy Center Wien, Urban Innovation GmbH), Anna Austaller (MA 20 – Department for energy planning, City of Vienna) Supported for the city chapters and with comments on the report by Amsterdam: Marijke Godschalk (City of Amsterdam, Department of Physical Planning and Sustainability), Saskia Müller Berlin: Heike Stock (City of Berlin, Department of Urban development and Housing), David Uong (BEA – Berlin Energy Agency) Paris: Sebastien Emery, Elsa Meskel et al (City of Paris, Environment department); Pierre Weber and Jérémie Jaeger (APC - Agence Parisienne du Climat Association) Stockholm: Lukas Ljungqvist et al (City of Stockholm, Planning administration) Vienna: Stefan Geier, Herbert Hemis (City of Vienna, MA20 – Department for energy planning); -

RED BANK Registertor AVI Depmtmtmu

tor AVI DepmtmtmU RED BANK REGISTER RE vo WaeM^sSMStea Se •»*»« Osss Matter el Us RANK M J THURSDAY. iTEPEMREft 2ft iflrM PACE ONE Local Club Honors Justice Brennan Council to Hear *»•".' Council Rejects Parley Plea for Market On Broad Street Plan FAIR HAVEN—The mayor and -*• council tonight will take under Werner May Succeed Council brushed aside objections consideration a recommendation by Mayor Katharine Elkus White of the zoning board of adjustment Kirkegwd on Council Monday night and refused to hold that It authorize a variance for Regional Bd. Plans a Joint public meeting with the the construction of a Davidson BATONTOWK — Herbert B. planning board on the Broad Bros, supermarket next to the Werner of M Ttaten in, may Street plan during the holiday fire house on River rd. be appelatei to succeed Harry season. The meeting will take place at N. Klrkegard as eeancUman at In doing so, It accepted the fact S p. m. at borough hall and Is ex- Wld night's mayor and Dec. 27 Meeting that the planning board could act pected to attract a sizable audi- on Ita own Initiative to adopt the ence since the matter has been In aaswer to ajiseattona freaa RITM8ON — The ntxt step to why voter* rejected the propois! plan. The- law givM the board one of. controversy that has been The Register, Mayor F. BUsa be taken by tht Rumson-Palr The board, prior to the refer- authority to take such action, talked about in a series of board Price yesterday aaU Mr. Wer- Haven regional high school board endum, said the cost of paying with no approval by the govern- meetings since Sept. -

Daniel Meadows Archive Library of Birmingham Contents of 209 Boxes

Daniel Meadows Archive Library of Birmingham contents of 209 boxes Box 1 Manchester Poly, art school year 1, 1970-71 1x 10x8 inch box Christmas show 1970 inc. picture of display and 5x4 colour transparencies 1x red A4 ring binder of 1st yr. photography theory notes Box 2 The Shop on Greame Street Modern work prints and discs 1x street guide Manchester A to Z 1x grey album of prints and cuttings 1x Creative Camera magazine (p.213 first published mention of the forthcoming bus project) 1x ring binder of pictures Box 3 Butlin's 1x 10x8 inch box: mounted 35mm slides, key fob viewer, telegrams, notebook, prints, postcards, wrapping paper, ID pass 1x red A4 ring binder: b&w prints, unmounted colour transparencies 1x red A4 ring binder: b&w prints, John Hinde postcards, Impressions Gallery 30th anniversary booklet, modern work prints and discs, original Impressions Gallery Butlin's exhibition poster artwork 2x 5x7 inch boxes: vintage colour enprints in card mounts as used in Library of Birmingham exhibition 2014 Box 4 June Street box of 1974 35mm transparencies showing houses boarded up discs of neg scans publications newspaper cuttings TV script (BBC Look North) vintage resin prints contact sheets (1990s) 1x colour enprint Craddock family complete set Metro Imaging digital prints 1x blue A4 pocket folder vintage (resin/fibre mixed up) prints 1x 12x16 inch box of 1990s fibre prints cellophane envelope 9x 10x12 inch vintage prints (5 signed Martin Parr/Daniel Meadows) Box 5 Bus Project (A) documentation re fundraising mostly catalogued 2010 by Newport intern Denise Myers (formerly Fotheringham) Box 6 Bus Project (B) items selected from Box 5 for exhibition wallpaper 1x book: British Image 1 inc. -

Q27 Casadevall EN.Pdf 103.65 KB

Political satire in Germany: from the political Kabarett of the thirties to Comedy TV Gemma Casadevall . Political satire in Germany is related to a tradition in- 1. Introduction herited from French cabaret but taken on as their own by a handful of intellectuals, principally left-wing, in the In Germany, talking about political humour means referring twenties and thirties of the last century: the so-called to a past quite a time before the birth of television and, political . Its roots in the political avant garde Kabarett essentially, to one word: Kabarett. This is a term adopted give it a prestige that survives to the present day as well from the original French word cabaret, also with connota- as a certain immunity to the media impact of other tions of a subculture, bohemian life and musicals but which mass TV products, such as Comedy TV. Hitler made in Germany, more than in other countries where this genre Kabarett the “political enemy” of the Third Reich, but the capitulation of Nazism also saw the rebirth of the genre, has also been taken on board, has a political aspect and is stronger than ever. Cabarets sprung up like mush- related to intellectuality, whether it takes place at night or rooms throughout Germany, although mainly in the two not. cities that had been the cradle for the genre, Berlin and The formula is the same: a small stage, an equally small Munich. A good cabaret artist knows no taboos: every- company with just a few actors, often monologue experts, thing is allowed, provided the subject is handled with and a mix of humour and satire with a certain carte blanche talent and they do not resort to silliness.