Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antibody–Drug Conjugates

Published OnlineFirst April 12, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0272 Review Clinical Cancer Research Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Future Directions in Clinical and Translational Strategies to Improve the Therapeutic Index Steven Coats1, Marna Williams1, Benjamin Kebble1, Rakesh Dixit1, Leo Tseng1, Nai-Shun Yao1, David A. Tice1, and Jean-Charles Soria1,2 Abstract Since the first approval of gemtuzumab ozogamicin nism of activity of the cytotoxic warhead. However, the (Mylotarg; Pfizer; CD33 targeted), two additional antibody– enthusiasm to develop ADCs has not been dampened; drug conjugates (ADC), brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris; Seat- approximately 80 ADCs are in clinical development in tle Genetics, Inc.; CD30 targeted) and inotuzumab ozogami- nearly 600 clinical trials, and 2 to 3 novel ADCs are likely cin (Besponsa; Pfizer; CD22 targeted), have been approved for to be approved within the next few years. While the hematologic cancers and 1 ADC, trastuzumab emtansine promise of a more targeted chemotherapy with less tox- (Kadcyla; Genentech; HER2 targeted), has been approved to icity has not yet been realized with ADCs, improvements treat breast cancer. Despite a clear clinical benefit being dem- in technology combined with a wealth of clinical data are onstrated for all 4 approved ADCs, the toxicity profiles are helping to shape the future development of ADCs. In this comparable with those of standard-of-care chemotherapeu- review, we discuss the clinical and translational strategies tics, with dose-limiting toxicities associated with the mecha- associated with improving the therapeutic index for ADCs. Introduction in antibody, linker, and warhead technologies in significant depth (2, 3, 8, 9). Antibody–drug conjugates (ADC) were initially designed to leverage the exquisite specificity of antibodies to deliver targeted potent chemotherapeutic agents with the intention of improving Overview of ADCs in Clinical Development the therapeutic index (the ratio between the toxic dose and the Four ADCs have been approved over the last 20 years (Fig. -

Cancer Drug Shortages: Who's Minding the Store?

✽ ✽ [ News ✽ Analysis ✽ Commentary ✽ Controversy ] February 25, 2011 Vol. 33 No. 4 oncology-times.com Publishing for O33 Years NCOLOGY The Independent TIMES Hem/Onc News Source Cancer Drug Shortages: Who’s Minding the Store? he recent shortages of certain chemotherapy agents and other key drugs raise Tquestions about who’s in charge of the national drug supply and how to ensure availability when there are limited fi nancial incentives and no mandates that manu- facturers notify the FDA about upcoming shortages. Here’s what experts are saying. Page 25 iStockphoto.com/klenova ASCO: For Patients with Advanced Cancer, Start Frank Talks about Options Soon after Diagnosis p.22 iStockphoto.com ODAC Backs FDA on Post-Marketing Medical Home Concept Comes Studies for Accelerated-Approval to Oncology p.45 Drugs p.8 [ ALSO ] SHOP TALK . 4 JOE SIMONE: The Self-Referral Boom . .15 MIKKAEL SEKERES: On (cology) Language . .16 Colorectal Cancer: Best to Start Chemo by 4 Weeks After Surgery . 18 Breast Cancer: 4 Cycles of Adjuvant Chemo Usually Suffi cient . 36 WENDY HARPHAM: ‘It’s OK’. 40 POETRY BY CANCER CAREGIVERS . 47 Ph+ ALL: Early Use of Imatinib Extends Long-Term Survival. 49 Twitter.com/OncologyTimes PERIODICALS bitly.com/oncologytimes 9 oncology times Saturating Liver Cancers with Chemotherapy Found to Extend Survival & Decrease Toxicity athing liver tumors in chemo- The study included 93 patients: said Charles Nutting, DO, FSIR, an Btherapy increases survival, accord- 44 received PHP and 49 had interventional radiologist at Swedish ing to a Phase III trial reported at the standard treatment (typically systemic Medical Center in Denver. -

Neuro-Ophthalmic Side Effects of Molecularly Targeted Cancer Drugs

Eye (2018) 32, 287–301 © 2018 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-222X/18 www.nature.com/eye 1,2,3 4 Neuro-ophthalmic side MT Bhatti and AKS Salama REVIEW effects of molecularly targeted cancer drugs Abstract The past two decades has been an amazing time culminated in indescribable violence and in the advancement of cancer treatment. Mole- unspeakable death. However, amazingly within cularly targeted therapy is a concept in which the confines of war have risen some of the specific cellular molecules (overexpressed, greatest advancements in medicine. It is within mutationally activated, or selectively expressed this setting—in particular World War II with the proteins) are manipulated in an advantageous study of mustard gas—that the annals of cancer manner to decrease the transformation, prolif- chemotherapy began touching the lives of eration, and/or survival of cancer cells. In millions of people. It is estimated that in 2016, addition, increased knowledge of the role of the over 1.6 million people in the United States will immune system in carcinogenesis has led to the be diagnosed with cancer and over a half a development of immune checkpoint inhibitors million will die.1 The amount of money being to restore and enhance cellular-mediated anti- spent on research and development of new tumor immunity. The United States Food and cancer therapies is staggering with a record $43 Drug Administration approval of the chimeric billion dollars spent in 2014. Nearly 30% of all monoclonal antibody (mAb) rituximab in 1997 registered clinical trials on the clinicaltrials.gov 1Department of for the treatment of B cell non-Hodgkin lym- website pertain to cancer drugs. -

Whither Radioimmunotherapy: to Be Or Not to Be? Damian J

Published OnlineFirst April 20, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2523 Cancer Perspective Research Whither Radioimmunotherapy: To Be or Not To Be? Damian J. Green1,2 and Oliver W. Press1,2,3 Abstract Therapy of cancer with radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies employing multistep "pretargeting" methods, particularly those has produced impressive results in preclinical experiments and in utilizing bispecific antibodies, have greatly enhanced the thera- clinical trials conducted in radiosensitive malignancies, particu- peutic efficacy of radioimmunotherapy and diminished its toxi- larly B-cell lymphomas. Two "first-generation," directly radiola- cities. The dramatically improved therapeutic index of bispecific beled anti-CD20 antibodies, 131iodine-tositumomab and 90yttri- antibody pretargeting appears to be sufficiently compelling to um-ibritumomab tiuxetan, were FDA-approved more than a justify human clinical trials and reinvigorate enthusiasm for decade ago but have been little utilized because of a variety of radioimmunotherapy in the treatment of malignancies, particu- medical, financial, and logistic obstacles. Newer technologies larly lymphomas. Cancer Res; 77(9); 1–6. Ó2017 AACR. "To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), which are not directly cytotoxic mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take for cancer cells but "release the brakes" on the immune system, arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them." Hamlet. allowing cytotoxic T cells to be more effective at recognizing –William Shakespeare. and killing cancer cells. Outstanding results have already been demonstrated with checkpoint inhibiting antibodies even in far Introduction advanced refractory solid tumors including melanoma, lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma and are under study for a multi- Impact of monoclonal antibodies on the field of clinical tude of other malignancies (4–6). -

B-Cell Targets to Treat Antibody-Mediated Rejection In

Muro et al. Int J Transplant Res Med 2016, 2:023 Volume 2 | Issue 2 International Journal of Transplantation Research and Medicine Commentary: Open Access B-Cell Targets to Treat Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Transplantation Manuel Muro1*, Santiago Llorente2, Jose A Galian1, Francisco Boix1, Jorge Eguia1, Gema Gonzalez-Martinez1, Maria R Moya-Quiles1 and Alfredo Minguela1 1Immunology Service, University Clinic Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Spain 2Nephrology Service, University Clinic Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Spain *Corresponding author: Manuel Muro, PhD, Immunology Service, University Clinic Hospital “Virgen de la Arrixaca”, Biomedical Research Institute of Murcia (IMIB), Murcia, Spain, Tel: 34-968-369599, E-mail: [email protected] Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) in allograft transplantation APRIL (a proliferation-inducing ligand). These co-activation signals can be defined with a rapid increase in the levels of specific are required for B-cell differentiation into plasma cell and enhancing serological parameters after organ transplantation, presence of donor their posterior survival and are a key determinant of whether specific antibodies (DSAs) against human leukocyte antigen (HLA) developing B-cells will survive or die during the establishment molecules, blood group (ABO) antigens and/or endothelial cell of immuno-tolerance [5,6]. Important used agents commercially antigens (e.g. MICA, ECA, Vimentin, or ETAR) and also particular available are Tocilizumab (anti-IL6R) and Belimumab (BAFF). histological parameters [1,2]. If the AMR persists or progresses, the The receptors of BAFF and APRIL could also be important as treatment to eliminate the humoral component of acute rejection eventual targets, for example BAFF-R, TACI (transmembrane include three sequential steps: (a) steroid pulses, antibody removal activator and calcium modulator and cyclophyllin ligand interactor) (plasma exchange or immuno-adsorption) and high doses of and BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen). -

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (Adcs) – Biotherapeutic Bullets

Sean L Kitson Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) – Biotherapeutic bullets SEAN L KITSON*, DEREK J QUINN, THOMAS S MOODY, DAVID SPEED, WILLIAM WATTERS, DAVID ROZZELL *Corresponding author Almac, Department of Biocatalysis and Isotope Chemistry, 20 Seagoe Industrial Estate, Craigavon, BT63 5QD, United Kingdom (chimeric human-murine IgG1 targeting EGF receptor) and KEYWORDS panitumumab (human IgG2 targeting EGF receptor) for the Antibody-drug conjugate; ADC; monoclonal antibody; treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (5). cancer; carbon-14; linker; immunotherapy. This technology of tailoring MAbs has been exploited to develop delivery systems for radionuclides to image and treat a variety of cancers (6). This led to the hypothesis that a ABSTRACT cancer patient would first receive a radionuclide antibody capable of imaging the tumour volume. The images of the Immunotherapies especially targeted towards oncology, tumour are obtained by using one or more combinations of based on antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have the following methods: planar imaging; single photon recently been boosted by the US Food and Drug emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron Administration approval of Adcetris to treat Hodgkin’s emission tomography (PET) (7). These techniques can be lymphoma and Kadcyla for metastatic breast cancer. extended to hybrid imaging systems incorporating PET (or The emphasis of this article is to provide an overview of SPECT) with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic the design of ADCs in order to examine their ability to 30 resonance imaging (MRI) (8). find and kill tumour cells. A particular focus will be on the relationship between the cytotoxic drug, chemical The imaging process is first used to locate the precise position linker and the type of monoclonal antibody (MAb) used of the tumour and ascertain the appropriate level of the to make up the components of the ADC. -

Antibody–Drug Conjugates: the Last Decade

pharmaceuticals Review Antibody–Drug Conjugates: The Last Decade Nicolas Joubert 1,* , Alain Beck 2 , Charles Dumontet 3,4 and Caroline Denevault-Sabourin 1 1 GICC EA7501, Equipe IMT, Université de Tours, UFR des Sciences Pharmaceutiques, 31 Avenue Monge, 37200 Tours, France; [email protected] 2 Institut de Recherche Pierre Fabre, Centre d’Immunologie Pierre Fabre, 5 Avenue Napoléon III, 74160 Saint Julien en Genevois, France; [email protected] 3 Cancer Research Center of Lyon (CRCL), INSERM, 1052/CNRS 5286/UCBL, 69000 Lyon, France; [email protected] 4 Hospices Civils de Lyon, 69000 Lyon, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 10 September 2020; Published: 14 September 2020 Abstract: An armed antibody (antibody–drug conjugate or ADC) is a vectorized chemotherapy, which results from the grafting of a cytotoxic agent onto a monoclonal antibody via a judiciously constructed spacer arm. ADCs have made considerable progress in 10 years. While in 2009 only gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg®) was used clinically, in 2020, 9 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved ADCs are available, and more than 80 others are in active clinical studies. This review will focus on FDA-approved and late-stage ADCs, their limitations including their toxicity and associated resistance mechanisms, as well as new emerging strategies to address these issues and attempt to widen their therapeutic window. Finally, we will discuss their combination with conventional chemotherapy or checkpoint inhibitors, and their design for applications beyond oncology, to make ADCs the magic bullet that Paul Ehrlich dreamed of. Keywords: antibody–drug conjugate; ADC; bioconjugation; linker; payload; cancer; resistance; combination therapies 1. -

Imatinib (Gleevec™)

Biologicals What Are They? When Did All of this Happen? There are Clear Benefits. Are there also Risks? Brian J Ward Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre Global Health, Immunity & Infectious Diseases Grand Rounds – March 2016 Biologicals Biological therapy involves the use of living organisms, substances derived from living organisms, or laboratory-produced versions of such substances to treat disease. National Cancer Institute (USA) What Effects Do Steroids Have on Immune Responses? This is your immune system on high dose steroids projects.accessatlanta.com • Suppress innate and adaptive responses • Shut down inflammatory responses in progress • Effects on neutrophils, macrophages & lymphocytes • Few problems because use typically short-term Virtually Every Cell and Pathway in Immune System ‘Target-able’ (Influenza Vaccination) Reed SG et al. Nature Medicine 2013 Nakaya HI et al. Nature Immunology 2011 Landscape - 2013 Antisense (30) Cell therapy (69) Gene Therapy (46) Monoclonal Antibodies (308) Recombinant Proteins (93) Vaccines (250) Other (81) http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/biologicsoverview2013.pdf Therapeutic Category Drugs versus Biologics Patented Ibuprofen (Advil™) Generic Ibuprofen BioSimilars/BioSuperiors ? www.drugbank.ca Patented Etanercept (Enbrel™) BioSimilar Etanercept Etacept™ (India) Biologics in Cancer Therapy Therapeutic Categories • Hormonal Therapy • Monoclonal antibodies • Cytokine therapy • Classical vaccine strategies • Adoptive T-cell or dendritic cells transfer • Oncolytic -

Hodgkin's Lymphoma Unresponsive to Rituximab Or a Rituximab

Clinical Development GSK1841157 Protocol OMB110918 / NCT01077518 A Randomized, Open Label Study of Ofatumumab and Bendamustine Combination Therapy Compared with Bendamustine Monotherapy in Indolent B-cell Non- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Unresponsive to Rituximab or a Rituximab-Containing Regimen During or Within Six Months of Treatment Authors Document type Amended Protocol Version EUDRACT number 2008-004177-17 Version number 11 Development phase III Document status Final Release date 13-Apr-2017 Novartis internal reference number COMB157E2301 Property of Novartis Confidential May not be used, divulged, published, or otherwise disclosed without the consent of Novartis Novartis Confidential Page 2 Amended Protocol Version 11 Clean Protocol No. COMB157E2301/OMB110918 Amendment 9 (13-Apr-2017) Amendment rationale The purpose of amendment 9 is to revise the total number of events required for the primary analysis of the primary end point PFS. The primary analysis was planned after reaching 259 PFS events as determined by an Independent Review Committee (IRC). Based on the current status of the study and PFS event count by IRC, it is highly unlikely that the 259 PFS events will be achieved. The study has been ongoing since September 2010 when the first patient was enrolled and the study sponsorship changed in February 2016 from GSK to Novartis (Amendment 8 , dated 18Mar2016). Per protocol, Interim Analysis for efficacy and futility and IDMC review occurred (22Feb2016) after 180 PFS events by IRC were reached (31Oct2015). IDMC recommended to continue the study without changes. The interim analysis of PFS was performed by an independent Statistical Data Analysis Centre. As per IDMC charter, unblinded results were not communicated to the sponsor in order to maintain the integrity of the trial. -

Ibritumomab Tiuxetan (Zevalin)

Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) Policy Number: Original Effective Date: MM.04.013 03/11/2003 Line(s) of Business: Current Effective Date: HMO; PPO 06/22/2012 Section: Prescription Drugs Place(s) of Service: Outpatient I. Description Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) is a CD20-directed radiotherapeutic antibody administered as part of the ibritumomab tiuxetan therapeutic regimen indicated for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory, low-grade or follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and for the treatment of patients with previously untreated follicular NHL who have achieved a partial or complete response to first-line chemotherapy. Ibritumomab tiuxetan is comprised of two separate components, indium-111(IN-111) the diagnostic component and yttrium-90 (Y-90) the therapeutic component. The ibritumomab tiuxetan regimen includes the administration of rituximab followed by IN-111, which targets and binds to the tumor cell. If the IN-111 binds successfully to the tumor cells, seven to nine days later, a second dose of rituximab is administered followed by Y-90 which damages the targeted tumor cells. II. Criteria/Guidelines A. The ibritumomab tiuxetan therapeutic regimen is covered (subject to Limitations/Exclusions and Administrative Guidelines) when recommended by an oncologist for the following conditions: 1. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) a. For the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory, low-grade or follicular B-cell NHL b. For the treatment of patients with follicular NHL who achieve a partial or complete response to first-line chemotherapy 2. For the indications listed above, the following criteria must be met: a. Lymphoma involvement of the bone is less than 25 percent Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) 2 b. -

Cetuximab Promotes Anticancer Drug Toxicity in Rhabdomyosarcomas with EGFR Amplificationin Vitro

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 30: 1081-1086, 2013 Cetuximab promotes anticancer drug toxicity in rhabdomyosarcomas with EGFR amplificationin vitro YUKI YAMAMOTO1*, KAZUMASA FUKUDA2*, YASUSHI FUCHIMOTO4*, YUMI MATSUZAKI3, YOSHIRO SAIKAWA2, YUKO KITAGAWA2, YASUHIDE MORIKAWA1 and TATSUO KURODA1 Departments of 1Pediatric Surgery, 2Surgery and 3Physiology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-858; 4Division of Surgery, Department of Surgical Subspecialities, National Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo 157-8535, Japan Received January 15, 2013; Accepted April 2, 2013 DOI: 10.3892/or.2013.2588 Abstract. Overexpression of human epidermal growth factor i.e., t(2;13) (q35;q14) in 55% of cases and t(1;13) (p36;q14) in receptor (EGFR) has been detected in various tumors and is 22% of cases (1). Current treatment options include chemo- associated with poor outcomes. Combination treatment regi- therapy, complete surgical resection and radiotherapy (3). mens with EGFR-targeting and cytotoxic agents are a potential However, the prognosis for patients with advanced-stage RMS therapeutic option for rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) with EGFR is quite poor (4). The main problems with clinical treatments amplification. We investigated the effects of combination include metastatic invasion, local tumor recurrence and multi- treatment with actinomycin D and the EGFR-targeting agent drug resistance. Therefore, more specific, effective and less cetuximab in 4 RMS cell lines. All 4 RMS cell lines expressed toxic therapies are required. wild-type K-ras, and 2 of the 4 overexpressed EGFR, as Numerous novel anticancer agents are currently in early determined by flow cytometry, real-time PCR and direct phase clinical trials. Of these, immunotherapy with specific sequencing. -

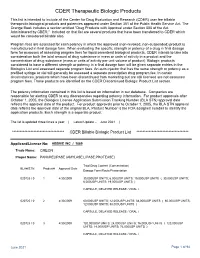

CDER Therapeutic Biologic Products List

CDER Therapeutic Biologic Products This list is intended to include all the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) user fee billable therapeutic biological products and potencies approved under Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act. The Orange Book includes a section entitled "Drug Products with Approval under Section 505 of the Act Administered by CBER." Included on that list are several products that have been transferred to CDER which would be considered billable also. Program fees are assessed for each potency in which the approved (non-revoked, non-suspended) product is manufactured in final dosage form. When evaluating the specific strength or potency of a drug in final dosage form for purposes of assessing program fees for liquid parenteral biological products, CDER intends to take into consideration both the total amount of drug substance in mass or units of activity in a product and the concentration of drug substance (mass or units of activity per unit volume of product). Biologic products considered to have a different strength or potency in a final dosage form will be given separate entries in the Biologics List and assessed separate program fees. An auto-injector that has the same strength or potency as a prefilled syringe or vial will generally be assessed a separate prescription drug program fee. In certain circumstances, products which have been discontinued from marketing but are still licensed are not assessed program fees. Those products are identified on the CDER Discontinued Biologic Product List section. The potency information contained in this list is based on information in our database.