The Influence of Bigleaf Maple on Forest Floor and Mineral Soil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar

Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Figured Wood in Poplar Youran Fan1,2, Keith Woeste1,2, Daniel Cassens1, Charles Michler1,2, Daniel Szymanski3, and Richard Meilan1,2 1Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, 2Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, and 3Department of Agronomy; Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract Materials and Methods When “Curly Aspen” (Populus canescens) was first Preliminary Results characterized in the early 1940’s[1], it attracted the attention from the wood-products industry because Genetically engineer commercially 1) Histological sections reveal that “Curly Aspen” has strong “Curly Aspen” produces an attractive veneer as a important trees to form figure. ray flecks (Fig. 10) but this is not likely to be responsible result of its figured wood. Birdseye, fiddleback and for the figure seen. quilt are other examples of figured wood that are 2) Of the 15 SSR primer pairs[6, 7, 8] tested, three have been commercially important[2]. These unusual grain shown to be polymorphic. Others are now being tested. patterns result from changes in cell orientation in Figure 6. Pollen collection. Branches of Figure 7. Pollination. Branches Ultimately, our genetic fingerprinting technique will allow “Curly Aspen” were “forced” to shed collected from a female P. alba us to distinguish “Curly Aspen” from other genotypes. the xylem. Although 50 years have passed since Figure 1. Birdseye in maple. pollen under controlled conditions. growing at Iowa State University’s finding “Curly Aspen”, there is still some question Rotary cut, three-piece book McNay Farm (south of Lucas, IA). 3) 17 jars of female P. alba branches have been pollinated match (origin: North America). -

Bigleaf Maple Decline in Western Washington

Bigleaf Maple Decline in Western Washington Jacob J. Betzen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2018 Committee: Patrick Tobin Gregory Ettl Brian Harvey Robert Harrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Environmental and Forest Sciences © Copyright 2018 Jacob Betzen University of Washington Abstract Bigleaf Maple Decline in Western Washington Jacob J. Betzen Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patrick Tobin School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum Pursh) is a prominent component of the urban and suburban landscape in Western Washington, which lies at the heart of the native range of A. macrophyllum. Acer macrophyllum performs many important ecological, economic, and cultural functions, and its decline in the region could have cascading impacts. In 2011, increases in A. macrophyllum mortality were documented throughout the distributional range of the species. Symptoms of this decline included a systemic loss of vigor, loss of transpiration, and a reduction in photosynthetic potential, but did not display any signs or symptoms indicative of a specific causative agent. No pathogenic microbes, insects, or other biotic agents were initially implicated in causing or predisposing A. macrophyllum to decline. In my thesis research, I quantified the spatial extent and severity of A. macrophyllum decline in the urban, suburban, and wildland forests of western Washington, identified potential abiotic and biotic disturbance agents that are contributing to the decline, and conducted a dendrochronological analysis to ascertain the timing of the decline. I surveyed 22 sites that were previously reported as containing declining A. macrophyllum, and sampled 156 individual A. -

Comparison of Oak and Sugar Maple Distribution and Regeneration in Central Illinois Upland Oak Forests

COmparisON OF OaK AND Sugar MAPLE DistriBUTION AND REGENEratiON IN CEntral ILLINOIS UPLAND OaK FOREsts Peter J. Frey and Scott J. Meiners1 Abstract.—Changes in disturbance frequencies, habitat fragmentation, and other biotic pressures are allowing sugar maple (Acer saccharum) to displace oak (Quercus spp.) in the upland forest understory. The displacement of oaks by sugar maples represents a major management concern throughout the region. We collected seedling microhabitat data from five upland oak forest sites in central Illinois, each differing in age class or silvicultural treatment to determine whether oaks and maples differed in their microhabitat responses to environmental changes. Maples were overall more prevalent in mesic slope and aspect positions. Oaks were associated with lower stand basal area. Both oaks and maples showed significant habitat partitioning, and environmental relationships were consistent across sites. Results suggest that management intensity for oak in upland forests could be based on landscape position. Maple expansion may be reduced by concentrating mechanical treatments in expected areas of maple colonization, while using prescribed fire throughout stands to promote oak regeneration. INTRODUCTION Historically, white oak (Quercus alba) dominated much of the midwestern and eastern U.S. hardwood forests (Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Franklin et al. 1993). Oak is classified as an early successional forest species, and many researchers agree that oak populations were maintained by Native American or lightning-initiated fires (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Hutchinson et al. 2008, Moser et al. 2006, Nowacki and Abrams 2008, Ruffner and Groninger 2006, Shumway et al. 2001). These periodic low to moderate surface fires favored the ecophysiological attributes of oak over those of fire-sensitive, shade-tolerant tree species, thereby continually resetting succession and allowing oaks and other shade-intolerant species to persist in both the canopy and understory (Abrams 2003, Abrams and Nowacki 1992, Crow 1988, Franklin et al. -

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable

Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forest State Rank: S3 - Vulnerable Mesic Forest (RMF): Sugar Maple - Oak - Hickory Forests are most occurrences of RMF diverse forests in central and eastern in Massachusetts are west Massachusetts where conditions, of the Connecticut River including nutrient richness, support Valley. The presence of Northern Hardwood species mixed with multiple species of species of Oak - Hickory Forests; hickories and oaks in SMOH is a main The herbaceous layer varies from sparse difference between these to intermittent, with sparse spring two types. Broad-leaved ephemerals that may include bloodroot or Woodland-sedge is close trout-lily. Later occurring species may to being an indicator of include wild geranium, herb Robert, wild SMOH. RMF is Rock outcrops in the spring in Sugar Maple - licorice, maidenhair fern, bottlebrush Oak - Hickory Forest area. Photo: Patricia characterized by very Swain, NHESP. grass, and white wood aster. Broad- dense herbaceous growth of spring leaved, semi-evergreen broad-leaved ephemerals; SMOH shares some of the Description: Sugar Maple - Oak - woodland-sedge is close to an indicator of species but with fewer individuals of Hickory Forests occur in or east of the the community. Witch hazel, hepaticas, fewer species. SMOH has evergreen Connecticut River Valley in and wild oats usually occur in transitions ferns, Christmas fern and wood ferns, that Massachusetts. They are associated with to surrounding forest types. RMF lack. Oak - Hickory Forests and outcrops of circumneutral rock and slopes Dry, Rich Oak Forests/Woodlands lack below them that have more nutrients than abundant sugar maple, basswood, and are available in the surrounding forest. -

BIGLEAF MAPLE Evening Grosbeaks, Chipmunks, Mice, and a Variety of Birds

Plant Guide Wildlife: The seeds provide food for squirrels, BIGLEAF MAPLE evening grosbeaks, chipmunks, mice, and a variety of birds. Elk and deer browse the young twigs, leaves, Acer macrophyllum Pursh and saplings. Plant Symbol = ACMA3 Agroforestry: Bigleaf maple can be planted on sites Contributed By: USDA NRCS National Plant Data infected with laminated rot for site rehabilitation. It Center can also accelerate nutrient cycling, site productivity, revegetate disturbed riparian areas, and contribute to long-term sustainability. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values. Description General: Maple Family (Aceraceae). Bigleaf maple is a native, long-lived medium to large sized deciduous tree that often grows to eighty feet tall. The leaves are simple, opposite, and very large between fifteen to thirty centimeters wide and almost as long (Farrar 1995). The flowers are yellow, Brother Alfred Brousseau © Saint Mary's College fragrant, and produced in noddling racemes @ CalPhotos appearing with the leaves in April or May. The fruit is paired, 2.5 - 4 centimeters long, and brown with Alternative Names stiff yellowish hair. The bark is smooth and gray- Oregon maple, broad leaf maple, big-leaf maple brown on young stems, becoming red-brown and deeply fissured, and broken into scales on the surface Uses (Preston 1989). Ethnobotanic: The inner bark was often dried and ground into a powder and then used as a thickener in Distribution: Acer macrophyllum is distributed soups or mixed with cereals when mixing bread. -

2021 Mwl 2 L

Schilletter - University SCHILLETTER - UNIVERSITY VILLAGE201R COMMUNITY 201B 201D 201N CENTER D A O APPLIED R GOLF COURSE SCIENCE 201P S MAINTENANCE T COMPLEX IV T OFFICE O T LONG ROAD S G DR NBUR IVE 201M BLANK201CE 201K 104 CLUBHOUSE APPLIED D SCIENCE A COMPLEX I O R 201L 102 G 201C APPLIED 103 N O SCIENCE L COMPLEX III APPLIED D SCIENCE 201J A O COMPLEX II 201H R WASTE S T CHEMICAL T 201F D 201G O HANDLING T 101 A S SENSITIVE BUILDING Veenker Memorial Golf Course O INSTRUMENT R FACILITY E LYNN G FUHRER N A LODGE T S 205 201E 201D 201B ISU FAMILY 200 RESOURCE CENTER 205 RIVE 201A BRUNER D Iow ay C reek D A O R L L O H Io C w S ay Cre ek Disc Golf Course 112 L 13 Veenker Memorial Golf Course TH S TRE Furnam Aquatic Center ET EXTENSION 4-H (City Of Ames) T 125 REE YOUTH BUILDING H ST 13T 112 J 124A 112 A 112 J 112 H EH&S ONTARIO STREET 122A ONTARIO STREET SERVICES 120A ROAD STANGE BUILDING 124 FRED115ERIKSEN 112 K 121 BLDG SERVICES COURT ADMINISTRATIVE 112 G HAWTHORN COURT COMMUNITY FREDERIKSEN WANDA DALEY DRIVE DRIVE CENTER COURT 112 K 112 K 122 LIBRARY 120 DOE STORAGE WAREHOUSE FACILITY 119 DOE DOE CONST D 112 D-1 MECH A DOE O R 29 MAINT DOE R PRINTING & E SHOP B ROY J. CARVER PUBLICATIONS31 A CO-LABORATORY BUILDING H 112N 29 NORTH CHILLED 112 B 112 F WATER PLANT ear Creek 112 C 112 D-2 Cl 28 28 Union Pacific Railroad 35 30 27 28A 33 Pammel Woods 12 MOLECULAR 28A FIRE SERVICE BIOLOGY BUILDING COMMUNICATIONS 32 A BUILDING METALS TRANSPORTATION S ADVANCED BUILDING 28A 110 DEVELOPMENT C RUMINANT I 32 TEACHING & HORSE BARN BUILDING T NUTRITION SERVICES E RESEARCH 79 STANGE ROAD STANGE N LAB Cemetery E BUILDING WINLOCK ROAD G LABORATORY MACH ADVANCED LAB SYSTEMS 11W 11E PAMMEL DRIVE NORTH UNIVERSITY BOULEVARD PAMMEL DRIVE SPEDDING WILHELM NATIONAL NATIONAL HYLAND AVENUE HYLAND 11 22 HACH HALL HALL HALL SCIENCE SWINE RSRCH LAB FOR AG. -

Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-Growth Douglas-Fir-Western Hemlock Forest

3589 David M. Braun, Bi Runcheng, David C. Shaw, and Mark VanScoy, University of Washington, Wind River Canopy Crane Research Facility, 1262 Hemlock Rd., Carson, Washington 98610 Folivory of Vine Maple in an Old-growth Douglas-fir-Western Hemlock Forest Abstract Folivory of vine maple was documented in an old-growth Douglas-fir-western hemlock forest in southwest Washington. Leaf consumption by lepidopteran larvae was estimated with a sample of 450 tagged leaves visited weekly from 7 May to 11 October, the period from bud break to leaf drop. Lepidopteran taxa were identified by handpicking larvae from additional shrubs and rearing to adult. Weekly folivory peaked in May at 1.2%, after which it was 0.2% to 0.7% through mid October. Cumulative seasonal herbivory was 9.9% of leaf area. The lepidopteran folivore guild consisted of at least 22 taxa. Nearly all individuals were represented by eight taxa in the Geometridae, Tortricidae, and Gelechiidae. Few herbivores from other insect orders were ob- served, suggesting that the folivore guild of vine maple is dominated by these polyphagous lepidopterans. Vine maple folivory was a significant component of stand folivory, comparable to — 66% of the folivory of the three main overstory conifers. Because vine maple is a regionally widespread, often dominant understory shrub, it may be a significant influence on forest lepidopteran communities and leaf-based food webs. Introduction tract to defoliator outbreaks, less is known about endemic populations of defoliators and low-level Herbivory in forested ecosystems consists of the folivory. consumption of foliage, phloem, sap, and live woody tissue by animals. -

A Guide to Priority Plant and Animal Species in Oregon Forests

A GUIDE TO Priority Plant and Animal Species IN OREGON FORESTS A publication of the Oregon Forest Resources Institute Sponsors of the first animal and plant guidebooks included the Oregon Department of Forestry, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Oregon State University and the Oregon State Implementation Committee, Sustainable Forestry Initiative. This update was made possible with help from the Northwest Habitat Institute, the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University and Oregon State University. Acknowledgments: The Oregon Forest Resources Institute is grateful to the following contributors: Thomas O’Neil, Kathleen O’Neil, Malcolm Anderson and Jamie McFadden, Northwest Habitat Institute; the Integrated Habitat and Biodiversity Information System (IBIS), supported in part by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council and the Bonneville Power Administration under project #2003-072-00 and ESRI Conservation Program grants; Sue Vrilakas, Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Institute for Natural Resources; and Dana Sanchez, Oregon State University, Mark Gourley, Starker Forests and Mike Rochelle, Weyerhaeuser Company. Edited by: Fran Cafferata Coe, Cafferata Consulting, LLC. Designed by: Sarah Craig, Word Jones © Copyright 2012 A Guide to Priority Plant and Animal Species in Oregon Forests Oregonians care about forest-dwelling wildlife and plants. This revised and updated publication is designed to assist forest landowners, land managers, students and educators in understanding how forests provide habitat for different wildlife and plant species. Keeping forestland in forestry is a great way to mitigate habitat loss resulting from development, mining and other non-forest uses. Through the use of specific forestry techniques, landowners can maintain, enhance and even create habitat for birds, mammals and amphibians while still managing lands for timber production. -

4-H Wood Science Leader Guide Glossary of Woodworking Terms

4-H Wood Science Leader Guide Glossary of Woodworking Terms A. General Terms B. Terms Used in the Lumber Industry d—the abbreviation for “penny” in designating nail boards—Lumber less than 2 inches in nominal size; for example, 8d nails are 8 penny nails, 2½” long. thickness and 1 inch and wider in width. fiber—A general term used for any long, narrow cell of board foot—A measurement of wood. A piece of wood wood or bark, other than vessels. that is 1 foot long by 1 foot wide by 1 inch thick. It can also be other sizes that have the same total amount grain direction—The direction of the annual rings of wood. For example, a piece of wood 2 feet long, showing on the face and sides of a piece of lumber. 6 inches wide, and 1 inch thick; or a piece 1 foot long, hardwood—Wood from a broad leaved tree and 6 inches wide, and 2 inches thick would also be 1 board characterized by the presence of vessels. (Examples: foot. To get the number of board feet in a piece of oak, maple, ash, and birch.) lumber, measure your lumber and multiply Length (in feet) x Width (in feet) x Thickness (in inches). The heartwood—The older, harder, nonliving portion of formula is written: wood. It is usually darker, less permeable, and more durable than sapwood. T” x W’ x L’ T” x W’ x L’ = Board feet or = Board feet 12 kiln dried—Wood seasoned in a humidity and temperature controlled oven to minimize shrinkage T” x W’ x L’ or = Board feet and warping. -

Street Tree Inventory Report Hillsdale Neighborhood August 2016 Street Tree Inventory Report: Hillsdale Neighborhood August 2016

Street Tree Inventory Report Hillsdale Neighborhood August 2016 Street Tree Inventory Report: Hillsdale Neighborhood August 2016 Written by: Kat Davidson, Angie DiSalvo, Julie Fukuda, Jim Gersbach, Jeremy Grotbo, and Jeff Ramsey Portland Parks & Recreation Urban Forestry 503-823-4484 [email protected] http://portlandoregon.gov/parks/treeinventory Hillsdale Tree Inventory Organizers: Jim Keiter Staff Neighborhood Coordinator: Jim Gersbach Data Collection Volunteers: Dennis Alexander, Richard Anderson, William Better, Ben Brady, Brian Brady, Julia Brown, Marty Crouch, Hannah Davidson, April Ann Fong, Lise Gervais, Margaret Gossage, Karen Henell, Jim Keiter, John Mills, Pat Ruffio, Jerry Sellers, Kristin Sellers, Mimi Siekmann, Haley Smith, Nancy Swaim, Mark Turner, Loris Van Pelt, Paige Witte, and Maggie Woodward Data Entry Volunteers: Michael Brehm, Nathan Riggsby, and Eric Watson Arborist-on-Call Volunteers: Will Koomjian GIS Technical Support: Josh Darling, Portland Parks & Recreation Financial Support: Portland Parks & Recreation Cover Photos (from top left to bottom right): 1) Colorful foliage on a golden Deodar cedar (Cedrus deodara 'Aurea'). 2) The deep green leaves of a quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). 3) Unusual peeling bark on a young madrone (Arbutus menziesii). 4) A vivid fuchsia bloom on a magnolia (Magnolia sp.) 5) The developing cone of a rare China-fir Cunninghamia( lanceolata). 6) Unusually shaped leaves on a tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). 7) The pendant foliage of a weeping giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum 'Pendulum'). 8) Multicolored scaly foliage on a variegated elkhorn cedar (Thujopsis dolobrata 'Variegata'). ver. 10/17/2016 Portland Parks & Recreation 1120 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 1302 Portland, Oregon 97204 (503) 823-PLAY Commissioner Amanda Fritz www.PortlandParks.org Director Mike Abbaté Contents Key Findings ......................................... -

Self-Guided Neighborhood Tree Tour Created by Bhopesh Bassi

BELLEVUE NEIGHBORHOOD TREE AMBASSADOR PROGRAM Self-Guided Neighborhood Tree Tour Created by Bhopesh Bassi Neighborhood: Kelsey Creek Park and Farm Starting point: Kelsey Creek Park and Farm parking lot at 410 130th Place SE Summary/Theme: Introduction to plant and animal ecosystem in and around Kelsey Creek Park and Farm. Kelsey Creek Farm Park in Bellevue is a largely overlooked gem. While the park is tucked in the heart of neighborhoods, it feels like an isolated country woods experience. You may have the impression of having traveled back in time as you move from the modern parking lot to a more rural feel as you hike into the forest. Kelsey Creek is Seattle's largest watershed. It runs right down the middle of the park, providing habitat for spawning Salmon, Peamouth and for an abundant population of migratory and resident birds. All lifeform here depends on and contributes to each other and the park is a rich ecosystem. Bring your binoculars along if you also want to watch birds on this tour. BELLEVUE NEIGHBORHOOD TREE AMBASSADOR PROGRAM This tree tour was developed by one of Bellevue’s Neighborhood Tree Ambassador volunteers. The goal of the Neighborhood Tree Ambassador program is to help build community support for trees in Bellevue. Trees are an important part of our community because they provide significant health and environmental benefits. Trees: • Remove pollutants from the air and water • Reduce stress and improve focus • Lower air temperature • Pull greenhouse gases from the atmosphere • Reduce flooding and erosion caused by rain Bellevue has a goal to achieve a 40% tree canopy across the entire city. -

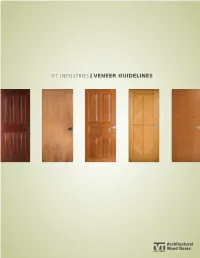

Veneer Guidelines 1

V T INDUSTRIES VENEER GUIDELINES 1 VTWO O D VENEERS PLAN I SLICED NATURAL MAPLE N ATURAL VARIATIONS The word natural brings to mind certain connotations like “beauty”, “warmth” and “purity”. Merriam-Webster defines natural as “occurring in conformity with the ordinary course of nature (the genetically controlled qualities of an organism): not marvelous or supernatural”. Wood is a product of nature, and in some cases, will accentuate and enhance a project design when used in its purest, or natural, state. However, as a product of nature, each wood species has certain intrinsic and industry-acceptable characteristics, which can vary from tree to tree and flitch (half log) to flitch. It is precisely these naturally occurring variations that provide such richness and uniqueness to each project design. Certain wood species such as natural maple and birch can vary widely in color range, which is why in many cases select white is specified so that the sapwood can be accumulated and spliced together to create a consistent color. The photos and information in this brochure are designed to assist you in specifying and receiving the product you envision. When specifying "natural" maple and birch, the veneer will contain unlimited amounts of Sapwood (the light portion of the log) and/or Heartwood (the dark portion of the log) unselected for color. If a light colored veneer is preferred, specify Select White (all Sapwood) maple or birch. If a dark colored veneer is preferred, specify Select Red/Brown (all Heartwood) Note, availability may be limited. 2 VTWO O D VENEERS PLAN I SLICED SELECT WHITE MAPLE HO W TO SPECIFY Natural veneers, such as maple and birch, may contain sapwood/ heartwood combinations, color streaks, spots and color variation from almost white to very dark.