10. Brief Notes on the Eodiscids 11, Phylogeny of the Dawsonidea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambrian Rocks of East Point, Nahant Massachusetts

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Conference Collection 1-1-1984 Cambrian rocks of East Point, Nahant Massachusetts Bailey, Richard H. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation Bailey, Richard H., "Cambrian rocks of East Point, Nahant Massachusetts" (1984). NEIGC Trips. 354. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/354 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Conference Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cl-1 249 CAMBRIAN ROCKS OF EAST POINT, NAHANT, MASSACHUSETTS Richard H. Bailey Department of Earth Sciences Northeastern University Boston, MA 02115 Introduction The quintessential stratigraphic component of Avalonian terranes of eastern North America is a Cambrian succession bearing the so-called Acado-Baltic trilobite assemblage. Spectacular sea cliffs at East Point, the easternmost extremity of Nahant, Massachusetts, afford an opportunity to examine a continuous and well exposed Lower Cambrian section on the Boston Platform. The Nahant Gabbro, sills, abundant dikes, and faults cut the Cambrian strata and add to the geological excitement. Indeed, it is difficult to move more t h a n a few meters along the cliffs without discovering a feature that will arouse your curiosity. This is also a wonderful place to watch waves crash against cliffs and to stare across the Atlantic in the direction of Africa. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites from Antarctica

Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites From Antarctica GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 456-D Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites From Antarctica By ALLISON R. PALMER and COLIN G. GATEHOUSE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF ANTARCTICA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 456-D Bio stratigraphy and regional significance of nine trilobite faunules from Antarctic outcrops and moraines; 28 species representing 21 genera are described UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-190734 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 70 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2071 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ ________________________ Dl Physical stratigraphy______________________________ D6 I&troduction. _______________________ 1 Regional correlation within Antarctica ________________ 7 Biostratigraphy _____________________ 3 Systematic paleontology._____-_______-____-_-_-----_ 9 Early Cambrian faunules.________ 4 Summary of classification of Antarctic Early and Australaspis magnus faunule_ 4 Chorbusulina wilkesi faunule _ _ 5 Middle Cambrian trilobites. ___________________ 9 Chorbusulina subdita faunule _ _ 5 Agnostida__ _ _________-____-_--____-----__---_ 9 Early Middle Cambrian f aunules __ 5 Redlichiida. __-_--------------------------_---- 12 Xystridura mutilinia faunule- _ 5 Corynexochida._________--________-_-_---_----_ -

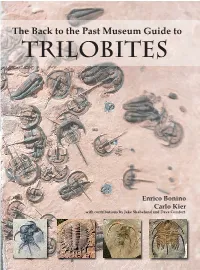

Th TRILO the Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILO BITES

With regard to human interest in fossils, trilobites may rank second only to dinosaurs. Having studied trilobites most of my life, the English version of The Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILOBITES by Enrico Bonino and Carlo Kier is a pleasant treat. I am captivated by the abundant color images of more than 600 diverse species of trilobites, mostly from the authors’ own collections. Carlo Kier The Back to the Past Museum Guide to Specimens amply represent famous trilobite localities around the world and typify forms from most of the Enrico Bonino Enrico 250-million-year history of trilobites. Numerous specimens are masterpieces of modern professional preparation. Richard A. Robison Professor Emeritus University of Kansas TRILOBITES Enrico Bonino was born in the Province of Bergamo in 1966 and received his degree in Geology from the Depart- ment of Earth Sciences at the University of Genoa. He currently lives in Belgium where he works as a cartographer specialized in the use of satellite imaging and geographic information systems (GIS). His proficiency in the use of digital-image processing, a healthy dose of artistic talent, and a good knowledge of desktop publishing software have provided him with the skills he needed to create graphics, including dozens of posters and illustrations, for all of the displays at the Back to the Past Museum in Cancún. In addition to his passion for trilobites, Enrico is particularly inter- TRILOBITES ested in the life forms that developed during the Precambrian. Carlo Kier was born in Milan in 1961. He holds a degree in law and is currently the director of the Azul Hotel chain. -

An Inventory of Trilobites from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74. 179 AN INVENTORY OF TRILOBITES FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS MEGAN R. NORR¹, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1 and JUSTIN S. TWEET2 1National Park Service. 1201 Eye Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20005; -email: [email protected]; 2Tweet Paleo-Consulting. 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove. MN 55016; Abstract—Trilobites represent an extinct group of Paleozoic marine invertebrate fossils that have great scientific interest and public appeal. Trilobites exhibit wide taxonomic diversity and are contained within nine orders of the Class Trilobita. A wealth of scientific literature exists regarding trilobites, their morphology, biostratigraphy, indicators of paleoenvironments, behavior, and other research themes. An inventory of National Park Service areas reveals that fossilized remains of trilobites are documented from within at least 33 NPS units, including Death Valley National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. More than 120 trilobite hototype specimens are known from National Park Service areas. INTRODUCTION Of the 262 National Park Service areas identified with paleontological resources, 33 of those units have documented trilobite fossils (Fig. 1). More than 120 holotype specimens of trilobites have been found within National Park Service (NPS) units. Once thriving during the Paleozoic Era (between ~520 and 250 million years ago) and becoming extinct at the end of the Permian Period, trilobites were prone to fossilization due to their hard exoskeletons and the sedimentary marine environments they inhabited. While parks such as Death Valley National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve have reported a great abundance of fossilized trilobites, many other national parks also contain a diverse trilobite fauna. -

Paradoxides Œlandicus Beds of Öland, with the Account of a Diamond

SVERIGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERSÖKNING SER. c. Avhandlingar och uppsatser. N:o 394· ÅRSBOK 30 (1936) N:o 1. PARADOXIDEs CELANDICUS BEDS OF ÖLAND WITH THE ACCOUNT OF A DIAMOND BORING THROUGH THE CAMBRIAN AT MOSSBERGA BY A. H. WESTERGÅRD Witlt Twelve Plates Pris 3:- kr. STOCKHOLM 1936 KUNGL. BOKTRYCKERIET. P. A. NORSTEDT & SÖNER 36!789 SVERIGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERS ÖKNING SER. c. Avhandlingar och uppsatser. N:o 394· ÅRSBOK 30 (1936) N:o r. PARADOXIDEs CELANDICUS BEDS OF ÖLAND WITH THE ACCOUNT OF A DIAMOND BORING THROUGH THE CAMBRIAN AT MOSSBERGA BY A. H. WESTERGÅRD With Twelve Plates STOCKI-IOLM 1936 KUNGL. BOKTRYCKERIET. P. A. NORSTEDT & SÖNER CONTENT S. Page I. A Diamond Boring through the Cambrian at Mossberga . 5 Quartzite . ... 5 Lower Cambrian Deposits and the Sub-Cambrian Land Surface 7 Paradoxides oolandicus Beds !3 Comparison of the Mossberga and Borgholm Profiles 16 II. Paradoxides oolandicus Beds of Öland . 17 Introduction and History . 17 Distribution, Thickness, and Stratigraphy 19 Acknowledgements 22 Fauna ..... 22 Brachiopoda . 22 M icromitra . 2 2 Lingulella 23 Acrothele . 24 Acrotreta .. 24 Orthoid brachiopod 25 Gastropoda 25 ffilandia .. 25 Hyolithidae 26 Trilobita . 27 Condylopyge 27 Peronopsis 28 Agnostus . 29 Calodiscus 30 Burlingia 32 Paradoxides 33 Ontogeny of Paradoxides 45 Ellipsocephalus 56 Bailiella . 58 Solenopleura . 59 Phyllocarida. Hymenocaris (?) 61 Geographical and Stratigraphical Distribution of the Fauna Elements 62 Bibliography . 64 Explanation of Plates . 67 I. A Diamond Boring through the Cambrian at Mossberga. As a part of the work carried out by the Electrical Prospecting Co. (A.-B. Elektrisk Malmletning) in order to search for gas in the Lower Cambrian of Öland, a deep boring was made in the autumn of 1933 into a little flat dome at Mossberga, about 12 km S of Borgholm. -

Bedrock Geology of the Cape St. Mary's Peninsula

BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF THE CAPE ST. MARY’S PENINSULA, SOUTHWEST AVALON PENINSULA, NEWFOUNDLAND (INCLUDES PARTS OF NTS MAP SHEETS 1M/1, 1N/4, 1L/16 and 1K/13) Terence Patrick Fletcher Report 06-02 St. John’s, Newfoundland 2006 Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey COVER The Placentia Bay cliff section on the northern side of Hurricane Brook, south of St. Bride’s, shows the prominent pale limestones of the Smith Point Formation intervening between the mudstones of the Cuslett Member of the lower Bonavista Formation and those of the overlying Redland Cove Member of the Brigus Formation. The top layers of this marker limestone on the southwestern limb of the St. Bride’s Syncline contain the earliest trilobites found in this map area. Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF THE CAPE ST. MARY’S PENINSULA, SOUTHWEST AVALON PENINSULA, NEWFOUNDLAND (INCLUDES PARTS OF NTS MAP SHEETS 1M/1, 1N/4, 1L/16 and 1K/13) Terence P. Fletcher Report 06-02 St. John’s, Newfoundland 2006 EDITING, LAYOUT AND CARTOGRAPHY Senior Geologist S.J. O’BRIEN Editor C.P.G. PEREIRA Graphic design, D. DOWNEY layout and J. ROONEY typesetting B. STRICKLAND Cartography D. LEONARD T. PALTANAVAGE T. SEARS Publications of the Geological Survey are available through the Geoscience Publications and Information Section, Geological Survey, Department of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 8700, St. John’s, NL, Canada, A1B 4J6. This publication is also available through the departmental website. Telephone: (709) 729-3159 Fax: (709) 729-4491 Geoscience Publications and Information Section (709) 729-3493 Geological Survey - Administration (709) 729-4270 Geological Survey E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.gov.nl.ca/mines&en/geosurv/ Author’s Address: Dr. -

Paradoxides CELANDICUS BEDS of ÖLAND

SVERIGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERSÖKNING SER. c. Avhandlingar och uppsatser. N:o 394· ÅRSBOK 30 (1936) N:o r. PARADOXIDEs CELANDICUS BEDS OF ÖLAND WITH THE ACCOUNT OF A DIAMOND BORING THROUGH THE CAMBRIAN AT MOSSBERGA BY A. H. WESTERGÅRD With T w elve Flates S TO C KH O LM 19 36 KUNGL . BOKTRYCKERIET . P. A. NORSTEDT & SÖNER 36!789 CON TENTS. Page I. A Diamond Boring through the Cambrian at Mossberga . 5 Quartzite . 5 Lower Cambrian Deposits and the Sub-Cambrian Land Surfa ~e 7 Paradoxides relandicus Beds . 13 Comparison of t he Mossberga a nd Borgholm Profiles r 6 II. Paradoxides relandicus Beds of Öland . I7 Introduction and History . I7 Distribution, Thickness, and Stratigraphy I g Acknow ledgements 22 Fauna . ... 22 Brachiopoda . 22 M icromitra. 22 Lingulella 23 Acrothele . 24 Aerotre/a . 2 4 Orthoid brachiopod 25 Gastropoda 25 CElandia .. 25 H yolithidae 26 Trilobita . 27 Condylopyge 27 Peronopsis 28 Agnostus . 29 Calodiscus 30 Burlingia 32 Paradoxides 33 Ontogeny of Paradoxides 45 Ellipsocephalus 56 Bailiella . ss Solenopleura . 59 Phyllocarida. Hymenocaris (?) 6r Geographical and Stratigraphical Distribution of the F auna E lements 62 Bibliography . 64 Explanation of Flates . .•. 67 I. A Diamond Boring through the Cambrian at Mossberga. As a part of the work carried out by the Electrical Prospecting Co. (A.-B. Elektrisk Malmletning) in order to search for gas in the Lower Cambrian of Öland, a deep boring was made in the autumn of 1933 into a little flat dome at Mossberga, about 12 km S of Borgholm. The Company had the courtesy to present the core to the Geological Survey, and thus the present writer had the opportunity of subjecting it to a doser investigation, the results of which are given below. -

Early Cambrian Trilobite Faunas and Correlations, Labrador Group, Southern Labrador—Western Newfoundland

EARLY CAMBRIAN TRILOBITE FAUNAS AND CORRELATIONS, LABRADOR GROUP, SOUTHERN LABRADOR—WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND Douglas Boyce1, Ian Knight1, Christian Skovsted2 and Uwe Balthasar3 1 - GSNL; 2 - Swedish Museum of Natural History; 3 – University of Plymouth, England. Paleontological, lithological and mapping studies of mixed siliciclastic‒carbonate rocks of the Labrador Group have been ongoing, since 1976, by the GSNL. Recent systematic litho- and bio-stratigraphic studies with Drs. Skovsted and Balthasar focus on trilobite and small shelly fossils (SSF), mostly in the Forteau Formation. At least 34 co-eval sections have been measured, and 434 fossiliferous samples have been collected; publication of trilobite and SSF systematics is in preparation. Dyeran to Topazan biostratigraphy, southern Labrador and western Newfoundland. Early Cambrian and early Middle Cambrian global and Laurentian series and stages (Hollingsworth, 2011). Distribution of the Trilobite Faunas Early Cambrian trilobite faunas occur throughout the Forteau Formation and in the lowest strata of the overlying Hawke Bay Formation. They divide into two broad faunas – Olenelloidea, mostly occur in deep-water shale and mudrocks, and Corynexochida, are hosted in shallow-water limestone, including archeocyathid reefs. The Devils Cove member, basal Forteau Formation - a regionally widespread pink Bonnia sp. nov. Boyce: latex replica of limestone - hosts Calodiscus lobatus (Hall, 1847), Elliptocephala logani (Walcott, partial, highly ornamented, spinose 1910), and Labradoria misera (Billings, 1861a). Calodiscus lobatus and E. logani range cranidium, Route 432, Great Northern Zacanthopsis sp. A Boyce: latex replica of Peninsula (GNP); it also occurs in the Deer high in the formation regionally, but L. misera is restricted to the lower 20 m of the partial cranidium, Mackenzie Mill member, Arm limestone, Mackenzie Mill member, formation in Labrador (includes archeocyathid reefs). -

Trilobite Fauna (Wuliuan Stage, Miaolingian Series, Cambrian) of the Lower Lakeview Limestone, Pend Oreille Lake, Idaho

Journal of Paleontology, Volume 94, Memoir 79, 2020, p. 1–49 Copyright © 2020, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/20/1937-2337 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2020.38 Trilobite fauna (Wuliuan Stage, Miaolingian Series, Cambrian) of the lower Lakeview Limestone, Pend Oreille Lake, Idaho Frederick A. Sundberg Research Associate, Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001, USA <[email protected]> Abstract.—The Lakeview Limestone is one of the westernmost Cambrian exposures in the northwestern United States and occurs on the western edge of the Montania paleotopographic high. These deposits occur between the deeper water deposits to the west and carbonate banks and intracratonic basins to the east and provide critical link between the regions. A re-investigation of the Cambrian trilobite faunas from the lower portion of the Lakeview Limestone, Pend Oreille Lake, Idaho, is undertaken due to the inadequate illustrations and descriptions provided by Resser (1938a). Resser’s type speci- mens and additional material are figured and described. The trilobite assemblages represent the Ptychagnostus praecur- rens Zone, Wuliuan Stage, Miaolingian Series and including two new taxa: Itagnostus idahoensis n. sp., and Utia debra n. sp. Because of the similarity between some species of Amecephalus from the Lakeview Limestone to specimens from the Chisholm Shale, Nevada, the type specimens of Amecephalus piochensis (Walcott, 1886) and Am. packi (Resser, 1935), Walcott’s and Resser’s type specimens are re-illustrate and their taxonomic problems are discussed. -

A Cambrian Meraspid Cluster: Evidence of Trilobite Egg Deposition in a Nest Site

PALAIOS, 2019, v. 34, 254–260 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2110/palo.2018.102 A CAMBRIAN MERASPID CLUSTER: EVIDENCE OF TRILOBITE EGG DEPOSITION IN A NEST SITE 1 2 DAVID R. SCHWIMMER AND WILLIAM M. MONTANTE 1Department of Earth and Space Sciences, Columbus State University, Columbus, Georgia 31907-5645, USA 2Tellus Science Museum, 100 Tellus Drive, Cartersville, Georgia, 30120 USA email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Recent evidence confirms that trilobites were oviparous; however, their subsequent embryonic development has not been determined. A ~ 6cm2 claystone specimen from the upper Cambrian (Paibian) Conasauga Formation in western Georgia contains a cluster of .100 meraspid trilobites, many complete with librigenae. The juvenile trilobites, identified as Aphelaspis sp., are mostly 1.5 to 2.0 mm total length and co-occur in multiple axial orientations on a single bedding plane. This observation, together with the attached free cheeks, indicates that the association is not a result of current sorting. The majority of juveniles with determinable thoracic segment counts are of meraspid degree 5, suggesting that they hatched penecontemporaneously following a single egg deposition event. Additionally, they are tightly assembled, with a few strays, suggesting that the larvae either remained on the egg deposition site or selectively reassembled as affiliative, feeding, or protective behavior. Gregarious behavior by trilobites (‘‘trilobite clusters’’) has been reported frequently, but previously encompassed only holaspid adults or mixed-age assemblages. This is the first report of juvenile trilobite clustering and one of the few reported clusters involving Cambrian trilobites. Numerous explanations for trilobite clustering behavior have been posited; here it is proposed that larval clustering follows egg deposition at a nest site, and that larval aggregation may be a homing response to their nest. -

Upper Lower Cambrian (Provisional Cambrian Series 2) Trilobites from Northwestern Gansu Province, China

Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2014, 63, 3, 123–143 doi: 10.3176/earth.2014.12 Upper lower Cambrian (provisional Cambrian Series 2) trilobites from northwestern Gansu Province, China a b c c Jan Bergström , Zhou Zhiqiang , Per Ahlberg and Niklas Axheimer a Department of Palaeozoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 5007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Xi’an Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, 438 East You Yi Road, Xi’an 710054, Peoples Republic of China; [email protected] c Department of Geology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 12, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden; [email protected], [email protected] Received 7 March 2014, accepted 24 June 2014 Abstract. Upper lower Cambrian (provisional Cambrian Series 2) trilobites are described from three sections through the Shuangyingshan Formation in the Beishan area, northwestern Gansu Province, China. The trilobite fauna is dominated by eodiscoid and ‘corynexochid’ trilobites, together representing at least ten genera: Serrodiscus, Tannudiscus, Calodiscus, Pagetides, Kootenia, Edelsteinaspis, Ptarmiganoides?, Politinella, Dinesus and Subeia. Eleven species are described, of which seven are identified with previously described taxa and four described under open nomenclature. The composition of the fauna suggests biogeographic affinity with Siberian rather than Gondwanan trilobite faunas, and the Cambrian Series 2 faunas described herein and from elsewhere in northwestern China seem to be indicative of the marginal areas of the Siberian palaeocontinent. This suggests that the Middle Tianshan–Beishan Terrane may have been located fairly close to Siberia during middle–late Cambrian Epoch 2. Key words: Trilobita, taxonomy, palaeobiogeography, lower Cambrian, Cambrian Series 2, Beishan, Gansu Province, China.