Discovering Two New Solo Works for Trombone: a History, Summary, and Preparation of Frank Gulino’S Sonata No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White Home Address: 23271 Rosewood Oak Park, MI 48237 (917) 273-7498 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.walterwhite.com EDUCATION Banff Centre of Fine Arts Summer Jazz Institute – Advanced study of jazz performance, improvisation, composition, and 1985-1988 arranging. Performances with Dave Holland. Cecil Taylor, Muhal Richard Abrahms, David Liebman, (July/August) Richie Beirach, Kenny Wheeler, Pat LaBarbara, Julian Priester, Steve Coleman, Marvin Smith. The University of Miami 1983-1986 Studio Music and Jazz, Concert Jazz Band, Monk/Mingus Ensemble, Bebop Ensemble, ECM Ensemble, Trumpet. The Juilliard School 1981-1983 Classical Trumpet, Orchestral Performance, Juilliard Orchestra. Interlochen Arts Academy (High School Grades 10-12) 1978-1981 Trumpet, Band, Orchestra, Studio Orchestra, Brass Ensemble, Choir. Interlochen Arts Camp (formerly National Music Camp) 8-weeks Summers, Junior Orchestra (principal trumpet), Intermediate Band (1st Chair), Intermediate Orchestra (principal), 1975- 1979, H.S. Jazz Band (lead trumpet), World Youth Symphony Orchestra (section 78-79, principal ’81) 1981 Henry Ford Community College Summer Jazz Institute Summer Classes in improvisation, arranging, small group, and big band performance. 1980 Ferndale, Michigan, Public Schools (Grades K-9) 1968-1977 TEACHING ACCOMPLISHMENTS Rutgers University, Artist-in-residence Duties included coaching jazz combos, trumpet master 2009-2010 classes, arranging classes, big band rehearsals and sectionals, private lessons, and five performances with the Jazz Ensemble, including performances with Conrad Herwig, Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Terrell Stafford, Sean Jones, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone, Mike Williams, and Paquito D’Rivera Newark, NY, High School Jazz Program Three day residency with duties including general music clinics and demonstrations for primary and secondary students, coaching of Wind Ensemble, Choir, Jan 2011 Jazz Vocal Ensemble, and two performances with the High School Jazz Ensemble. -

Recital Report

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1975 Recital Report Robert Steven Call Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Call, Robert Steven, "Recital Report" (1975). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 556. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/556 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECITAL REPORT by Robert Steven Call Report of a recital performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OP MUSIC in ~IUSIC UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1975 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to expr ess appreciation to my private music teachers, Dr. Alvin Wardle, Professor Glen Fifield, and Mr. Earl Swenson, who through the past twelve years have helped me enormously in developing my musicianship. For professional encouragement and inspiration I would like to thank Dr. Max F. Dalby, Dr. Dean Madsen, and John Talcott. For considerable time and effort spent in preparation of this recital, thanks go to Jay Mauchley, my accompanist. To Elizabeth, my wife, I extend my gratitude for musical suggestions, understanding, and support. I wish to express appreciation to Pam Spencer for the preparation of illustrations and to John Talcott for preparation of musical examp l es. iii UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1972 - 73 Graduate Recital R. -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

A Curriculum for Tuba Performance in a Commercial Brass

A CURRICULUM FOR TUBA PERFORMANCE IN A COMMERCIAL BRASS QUINTET BY PAUL CARLSON Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Daniel Perantoni __________________________________ Kyle Adams __________________________________ Jeffrey Nelsen __________________________________ John Rommel ii Preface While a curriculum for any type of performance could be synthesized by theoretical reasoning based upon knowledge of how to learn any new genre or style of music, it is tradition that students turn to leaders in the field to gain insight and knowledge into the specific craft that they wish to pursue. While pure scholarship and study of a repertoire is an excellent way to gain insight into a performance arena, time spent in the field actually performing a certain style of music as a member of a professional ensemble gives a perspective that is intrinsically valuable to a project such as this. In addition to the sources listed in the bibliography and the extensive research done concerning this project, I have been a member of the Dallas Brass Quintet since September of 2010. I currently continue to serve as their tubist. Being a member of this ensemble, which is one of the most active touring commercial styled brass quintets in existence today, has greatly informed me concerning this project in terms of the demands of this type of performance. As I prepared to write this document, I took inventory of the skills and preparation that have allowed me to perform successfully in a commercial brass quintet. -

Fall 2010 (.Pdf)

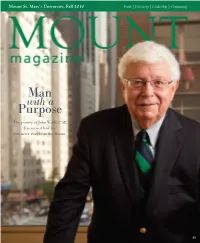

Mount St. Mary’s University, Fall 2010 Faith | Discovery | Leadership | Community Man with a Purpose The journey of John Walsh, C’58, has carried him far, but never away from the Mount. $5 President’s Letter Left: Opening Mass of the Holy Spirit held August 25. Below: Catie Carnes The new academic year could family, her classmates and and account for a life well lived. campus where the four pillars of not have started better. On a faculty needed help and support, We were strongly reminded of faith, discovery, leadership and beautiful Sunday in August, 430 and the campus community the Gospel admonition to “be community provide strength to Dearnew freshmen and theirFriends, parents needed information and a plan prepared, for at an hour you do support us all. arrived and were welcomed by of action. Fortunately, here not expect …” (Luke 12:40). an enthusiastic and skilled team at the Mount we practice for It is my hope that the tragedy of of 150 students, faculty and staff. campus emergencies, expect the In a larger sense, we are Catie’s sudden death will help The Seminary was full, with unexpected and have a quick comforted because, as a our students mature in respect its 166 men already back and and rapid response system in Catholic university, faith is our for their own lives and their into their orientation routine. place. Yet, no matter how much first pillar and the center that relationship with others. So as It is always great to witness the we prepare, the tears still come. brings us together. -

Symphonic Santa Sunday!

❆ AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION! HOLIDAY GREETINGS from MR. & MRS. FERRIS, 1917 FERRIS STATE UNIVERSITY The whole world is longing and praying for a "Merry Christmas," because the spirit of Christ “CHRISTMAS SING-A-LONG” has not dominated mankind in the ages past. The world is engaged in a life and death struggle. For more than three years the wanton destruction of human life has gone on. Millions of homes are crushed and the cry of anguish is heard 'round the world. Underneath this cry hope OFFICE OF INSTRUMENTAL CONCERT ENSEMBLES Hark, the Herald Angels Sing lingers, the hope that illumines Christmas, the only hope that saves. in charitable support of Hark, the Herald Angels Sing, “Glory to the new-born King!” Now as never before, man's hope, the world's hope, comes from Bethlehem. Forsake this hope, Peace on Earth and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled. and humanity is lost - eternal night reigns. A better and more glorious day is coming, another The Salvation Army Joyful, all ye nations rise, Join the triumph of the skies Christmas is coming and another. By and by hate will give way to love. Let your hearts go out to all the nations of the earth. With angelic host proclaim, “Christ is born in Bethlehem.” ❆ Hark, the Herald Angels Sing, “Glory to the new-born King!” To father and mother, brother and sister, and immediate friends give no Christmas token that presents has a money value. Give to all those who are safe from the devastation of war, words of ❆ greeting, words that shall quicken the pulse, words of love that shall forever linger in memory. -

Band Arranging

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1937 Band Arranging Frederic Barker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Barker, Frederic, "Band Arranging" (1937). Graduate Thesis Collection. 246. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/246 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C' '" MND A.~WiGING By r iTIUERIC ;: A.1KER Thesis presented for the Degroo of Master of Music in l~ei: Education -) ')." f iS 7 The Arthur Jordan Coneervatory of BusiC Approved by: Miss Ada Bicking T14 £1:,.5 ~~lf t. l' 7R" ~ L[) 7a. ,8pc2h f.3rJl! B.t1.r UlliTf>rlih mJfdan Collele of Mulil PRE!'ACB It is the purpo~~ of this theGis to establish a plan of pro cedure .. hioh _y serve as an aid in assisting the student of ~re.ng ing to meet the required needs of the military hand. Two essential methods may he pursued, the practical and the artistic. "The practical Inethod requires a thorough knowledge of the variou8 instruments, their range, registers, tonal quality and color, peculiarities of fingerin~, effective possibilities etc., as well D8 the necessary understanding for individual and collective use of all the instruments. The artistic method, on the contrary, cannot be ac quired beyond a certain degree, and whib it may be aesimilated in a small measure through analysis and study or the works of great com po~erD, it must, for the greater part at least, be natural and inborn. -

We Love Big Brother: an Analysis of the Relationship Between Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and Modern Politics in the United S

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-4-2018 We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty- Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe Edward Pankowski [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Pankowski, Edward, "We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe" (2018). Honors Scholar Theses. 559. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/559 We Love Big Brother: An Analysis of the Relationship between Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four And Modern Politics in the United States and Europe By Edward Pankowski Professor Jennifer Sterling-Folker Thesis Adviser: Professor Sarah Winter 5/4/2018 POLS 4497W Abstract: In recent months since the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency of the United States in November 2016, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has seen a resurgence in sales, and terms invented by Orwell or brought about by his work, such as “Orwellian,” have re- entered the popular discourse. This is not a new phenomenon, however, as Nineteen Eighty-Four has had a unique impact on each of the generations that have read it, and the impact has stretched across racial, ethnic, political, and gender lines. This thesis project will examine the critical, popular, and scholarly reception of Nineteen Eighty-Four since its publication 1949. Reviewers’ and commentators’ references common ideas, themes, and settings from the novel will be tracked using narrative theory concepts in order to map out an understanding of how the interpretations of the novel changed over time relative to major events in both American and Pankowski 1 world history. -

Rock, Rhythm, & Soul

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notes NO. 13 / WINTER 2008-2009 Rock, Rhythm, & Soul: The Black Roots of Popular Music liner notes final 031009.indd 1 3/10/09 5:37:14 PM aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and dissemination of materials for the purpose of research and I write this column on January music critics and scholars to discuss study of African American 20, 2009, the day our country and the socio-political history, musical music and culture. the world witnessed history being developments, and the future of black www.indiana.edu/~aaamc made with the swearing-in of the 44th rock musicians and their music. The President of the United States, Barack AAAMC will host one panel followed Obama, the first African American by a light reception on the Friday elected to the nation’s highest office. afternoon of the conference and two Table of Contents The slogan “Yes We Can” that ushered panels on Saturday. The tentative in a new vision for America also fulfills titles and order of the three panels are From the Desk of part of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “What Is Rock: Conceptualization and the Director ......................................2 dream for a different America—one Cultural Origins of Black Rock,” “The that embraces all of its people and Politics of Rock: Race, Class, Gender, Featured Collection: judges them by the content of their Generation,” and “The Face of Rock Patricia Turner ................................4 character rather than the color or their in the 21st Century.” In conjunction skin. -

S U M M E R 2 0

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

October 2017: Celebrating Lalo

AFM LOCAL 47 Vol. 3 No. 10 October 2017 online Celebrating Lalo An 85th Birthday Concert Celebration With a Film Music Legend We’ve Moved! New Rehearsal Rooms Next General Membership Meeting Learn what’s opening in early October! October 23 - Burbank, CA happening at our new home in Burbank online ISSN: 2379-1322 Publisher Editor: Gary Lasley AFM Local 47 3220 Winona Ave. Managing Editor: Linda A. Rapka Burbank CA 91504 Assistant Layout Editor: Candace Evans p 323.462.2161 f 323.993.3195 Advertising Manager: Karen Godgart www.afm47.org AFM LOCAL 47 EXECUTIVE BOARD Election Board & COMMITTEES Mark Zimoski, chair Overture Online is the official monthly Stephen Green, Scott Higgins, electronic magazine of the American Fed- Titled Officers Marie Matson, Kris Mettala, eration of Musicians Local 47. President John Acosta Paul Sternhagen, Nick Stone Vice President Rick Baptist Secretary/Treasurer Gary Lasley Fair Employment Practices Formed by and for Los Angeles musicians Committee Trustees Ray Brown, Beverly Dahlke-Smith over a century ago, Local 47 promotes and Judy Chilnick, Dylan Hart, protects the concerns of musicians in all Bonnie Janofsky Grievance Committee Ray Brown, Lesa Terry areas of the music business. Our jurisdic- Directors tion includes all counties of Los Angeles Pam Gates, John Lofton, Hearing Representative (except the Long Beach area). With more Andy Malloy, Phil O’Connor, Vivian Wolf Bill Reichenbach, Vivian Wolf than 7,000 members, Local 47 negotiates Legislative Committee with employers to establish fair wages Hearing Board Jason Poss, chair Allen Savedoff, chair Kenny Dennis, Greg Goodall, and working conditions for our members.