A Curriculum for Tuba Performance in a Commercial Brass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records to Consider

VOLUME XXIII BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1992 Dec 12-13, 1992 Vocals have always been with BBJ PROGRAMS are subject to change due to un SINGING GROUPS us, even though swing pur avoidable circumstances or station convenience. Many ists tend to overlook the con requests are receivedfor tape copies o f the programs, tribution made by lyrics in popularizing the Big Bands but stringent copyright laws applying to the records that are the basis of it all. The Mills Brothers, the Pied used prevent us from supplying such copies. Pipers, the Sentimentalists, the Modernaires, the Ink Spots, the Stardusters and the Merry Macs all make ( RECORDS TO CONSIDER) recorded appearances on this salute to the vocal groups, along with a few instrumental and single vocal HERE’S THAT SWING THING Pat Longo hits of the forties. Orchestra -Vocals by Frank Sinatra, Jr. USA Records - 19 Cuts - CD or Cassette Dec 19-20, 1992 It’s a very special BIG BAND CHRISTMAS time with very special Billy May was one of the arrangers for this recording, music, captured as which immediately makes it a must-have. Pat Longo’s performed in the studio and in broadcasts during the Orchestra has a two decade history of solid perfor Christmas seasons of years past. Both Big Bands and mance, some of it a bit far out for some Big Band single vocalists recall the Sounds of Christmas in a traditionalists, but most simply solid swing. Sax man simpler time; perhaps a better time. Recollections of Longo was vice-president of a California bank until he Christmas experiences fill in the moments between the realized money wasn’t what he wanted to handle the music to weave a spell. -

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

J. Dorsey, Earl Hines Also Swell Trombone Showcased

DOWN BEAT Chicago. April 15. 1941 Chicago fl by his latest cutting. Everything Depends On You, in which he spots Gems of Jazz’ and Kirby Madeline Green and a male vocal trio. On BBird 11036, it’s a side which shows a new Hines, a Hines who can bow to the public’s de Albarns Draw Big Raves; mands and yet maintain a high artistic plane. Backer is In Suiamp Lande, a juniper, with the leader’s I—Oh Le 88, Franz Jackson’s tenor and a »—New ' J. Dorsey, Earl Hines Also swell trombone showcased. Je Uy, 3—dmapi Jelly (BBird 11065) slow 4—Perfid by DAVE DEXTER, JR. blues with more sprightly Hines, 5—The A and a Pha Terrelish v ical by Bill 6—High I JvlUSICIANS SHOULD FIND the new “Gems of Jazz” and Eckstein. Flipover, I’m Falling 7—There' For You, is the only really bad John Kirby albums of interest, for the two collections em side of the four. It’s a draggy pop 9—Chapeí brace a little bit of everything in the jazz field. The “Gems” with too much Eckstein. [O—Th> l include 12 exceptional sides featuring Mildred Bailey, Jess 11—f Unti Stacy, Lux Lewis, Joe Marsala and Bud Freeman. Made in Jimmy Dorsey 12—Frenes 1936, they’ were issued only in England on Parlophone and Hot as a gang of ants on a WATCH O have been unavailable domestically until now. warm rock, Jim and his gang click again with two new Tudi« Cama Ma «mvng tl B a i 1 ey’s rata versions uf Yours (the Man Behind the Counter in soda-jerk getup in that rat. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

The Most Common Orchestral Excerpts for the Horn: a Discussion of Performance Practice

The most common orchestral excerpts for the horn: a discussion of performance practice by Shannon L. Armer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr. J. deC Hinch Pretoria January 2006 © University of Pretoria ii ABSTRACT This study describes in detail the preparation that must be done by aspiring orchestral horn players in order to be sufficiently ready for an orchestral audition. The general physical and mental preparation, through to the very specific elements that require attention when practicing and learning a list of orchestral excerpts that will be performed for an audition committee, is investigated. This study provides both the necessary tools and the insight borne of a number of years of orchestral experience that will enable a player to take a given excerpt and learn not only the notes and rhythms, but also discern many other subtleties inherent in the music, resulting in a full understanding and mastery thereof. Ten musical examples are included in order to illustrate the type of additional information that a player must gain so as to develop an in-depth knowledge of an excerpt. Three lists are presented within the text of this study: 1) a list of excerpts that are most commonly found at auditions, 2) a list of those excerpts that are often included and 3) other excerpts that have been requested but are not as commonly found. Also included is advice regarding the audition procedure itself, a discussion of the music required for auditions, and a guide to the orchestral excerpt books in which these passages can be found. -

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ______

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ____________________________________________________ n 1955 Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock was the first rock and roll record to become number one on the hit parade. It had made a stunning introduction in I the opening moments to a film called Blackboard Jungle. But at that time my favourite record was one by Lionel Hampton. I was not alone. Me and my three jazz loving friends couldn’t be bothered spending hard-earned cash on rock and roll records. Our quartet consisted of clarinet, drums, bass and vocal. Robert (nickname Orgy) was learning clarinet; Malcolm (Slim) was going to learn drums (which in due course he did under the guidance of Gordon LeCornu, a percussionist and drummer in the days when Sydney still had a thriving show scene); Dave (Bebop) loved the bass; and I was the vocalist a la Joe (Bebop) Lane. We were four of 120 RAAF apprentices undergoing three years boarding school training at Wagga Wagga RAAF Base from 1955-1957. Of course, we never performed together but we dreamt of doing so and luckily, dreaming was not contrary to RAAF regulations. Wearing an official RAAF beret in the style of Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie, however, was. Thelonious Monk wearing his beret the way Dave (Bebop) wore his… PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM P GOTTLIEB _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White Home Address: 23271 Rosewood Oak Park, MI 48237 (917) 273-7498 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.walterwhite.com EDUCATION Banff Centre of Fine Arts Summer Jazz Institute – Advanced study of jazz performance, improvisation, composition, and 1985-1988 arranging. Performances with Dave Holland. Cecil Taylor, Muhal Richard Abrahms, David Liebman, (July/August) Richie Beirach, Kenny Wheeler, Pat LaBarbara, Julian Priester, Steve Coleman, Marvin Smith. The University of Miami 1983-1986 Studio Music and Jazz, Concert Jazz Band, Monk/Mingus Ensemble, Bebop Ensemble, ECM Ensemble, Trumpet. The Juilliard School 1981-1983 Classical Trumpet, Orchestral Performance, Juilliard Orchestra. Interlochen Arts Academy (High School Grades 10-12) 1978-1981 Trumpet, Band, Orchestra, Studio Orchestra, Brass Ensemble, Choir. Interlochen Arts Camp (formerly National Music Camp) 8-weeks Summers, Junior Orchestra (principal trumpet), Intermediate Band (1st Chair), Intermediate Orchestra (principal), 1975- 1979, H.S. Jazz Band (lead trumpet), World Youth Symphony Orchestra (section 78-79, principal ’81) 1981 Henry Ford Community College Summer Jazz Institute Summer Classes in improvisation, arranging, small group, and big band performance. 1980 Ferndale, Michigan, Public Schools (Grades K-9) 1968-1977 TEACHING ACCOMPLISHMENTS Rutgers University, Artist-in-residence Duties included coaching jazz combos, trumpet master 2009-2010 classes, arranging classes, big band rehearsals and sectionals, private lessons, and five performances with the Jazz Ensemble, including performances with Conrad Herwig, Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Terrell Stafford, Sean Jones, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone, Mike Williams, and Paquito D’Rivera Newark, NY, High School Jazz Program Three day residency with duties including general music clinics and demonstrations for primary and secondary students, coaching of Wind Ensemble, Choir, Jan 2011 Jazz Vocal Ensemble, and two performances with the High School Jazz Ensemble. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

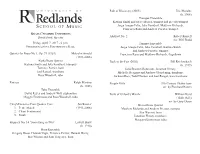

Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, Director Abstract No

Path of Discovery (2005) Eric Morales (b. 1966) Trumpet Ensemble Katrina Smith and Steve Morics, trumpet and piccolo trumpet Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Matthew Richards, Francisco Razo and Andrew Priester, trumpet Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, director Abstract No. 2 Robert Russell Arr. Wiff Rudd Friday, April 7, 2017 - 6 p.m. Trumpet Ensemble Frederick Loewe Performance Hall Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Katrina Smith and Andrew Priester, trumpet Quintet for Brass No.1, Op. 73 (1961) Malcolm Arnold Francisco Razo and Matthew Richards, flugelhorn (1921-2006) Alpha Brass Quintet Back to the Fair (2002) Bill Reichenbach Katrina Smith and Jake Ferntheil, trumpets (b. 1949) Terrence Perrier, horn Julia Broome-Robinson, Jonathan Heruty, Joel Rangel, trombone Michelle Reygoza and Andrew Glendening, trombone Ross Woodzell, tuba Jackson Rice, Todd Thorsen and Joel Rangel, bass trombone Fantasy Ralph Martino Simple Gifts 19th Century Shaker tune (b. 1945) arr. by Eberhard Ramm Tuba Ensemble David Reyes and Andrew Will, euphonium Earle of Oxford’s Marche William Byrd Maggie Eronimous and Ross Woodzell, tuba (1540-1623) arr. by Gary Olson Cinq Miniatures Pour Quatres Cors Jan Kotsier Bravo Brass Quintet 1. Petite March (1911-2006) Matthew Richards and Andrew Priester, trumpet 2. Chant Sentimental Star Wasson, horn 5. Finale Jonathan Heruty, trombone Margaret Eronimous, tuba Frippery No. 14 “Something in Two” Lowell Shaw (b. 1930) Horn Ensemble Gregory Reust, Hannah Vagts, Terrence Perrier, Hannah Henry, Star Wasson and Sam Tragesser, horn Fanfares Liturgiques Henri Tomasi from his London Philharmonic Orchestra days is revealed by his expert i. Annonciation (1901-1971) use of the contrast of tone color and timbre of the brass family in different ii. -

Developing a Beautiful Brass Sound (Part 1) by Joe W

Issue: Jan-March 2015 Subscription: 6/20/2011 to 3/7/2017 Developing a Beautiful Brass Sound (Part 1) by Joe W. Neisler This discussion was developed for horn students, but works well for all brass. Sound is the first thing we notice and the last thing we remember about any performance. Tone is the most important aspect of our playing. Every note we play demonstrates our sound, good or bad. Our sound is a critical aspect of our musical personality and fingerprint. The following ideas will help develop a beautiful brass sound. TONE CONCEPT We must have a very definite concept of a beautiful tone in order to produce a great sound. Conception of tone is a mental memory, aural visualization, imagination or recollection of what a beautiful tone sounds like. We cannot imagine or remember what we have not heard and memorized so we must frequently listen to fine players live and on recordings. Daily listening to recordings of fine players will develop our concept of tone. iTunes, YouTube, television and movie sound tracks, orchestra and military band recordings make it easier than ever to find wonderful recordings of great artists. Playing along with recordings on the mouthpiece, a mouthpiece rim/visualizer or a muted instrument helps imprint the aural role model and imitation in our minds. We should listen, imitate and compare our sounds to the great artists of our instrument. Horn players should listen to recordings by Barry Tuckwell, Hermann Baumann, Dennis Brain, Dale Clevenger, Eric Ruske and many other great artists. Daily listening is not enough. -

Recital Report

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1975 Recital Report Robert Steven Call Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Call, Robert Steven, "Recital Report" (1975). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 556. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/556 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECITAL REPORT by Robert Steven Call Report of a recital performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OP MUSIC in ~IUSIC UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1975 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to expr ess appreciation to my private music teachers, Dr. Alvin Wardle, Professor Glen Fifield, and Mr. Earl Swenson, who through the past twelve years have helped me enormously in developing my musicianship. For professional encouragement and inspiration I would like to thank Dr. Max F. Dalby, Dr. Dean Madsen, and John Talcott. For considerable time and effort spent in preparation of this recital, thanks go to Jay Mauchley, my accompanist. To Elizabeth, my wife, I extend my gratitude for musical suggestions, understanding, and support. I wish to express appreciation to Pam Spencer for the preparation of illustrations and to John Talcott for preparation of musical examp l es. iii UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1972 - 73 Graduate Recital R. -

From Jay-Z to Dead Prez: Examining Representations of Black

JBSXXX10.1177/0021934714528953Journal of Black StudiesBelle 528953research-article2014 Article Journal of Black Studies 2014, Vol. 45(4) 287 –300 From Jay-Z to Dead © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: Prez: Examining sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0021934714528953 Representations of jbs.sagepub.com Black Masculinity in Mainstream Versus Underground Hip-Hop Music Crystal Belle1 Abstract The evolution of hip-hop music and culture has impacted the visibility of Black men and the Black male body. As hip-hop continues to become commercially viable, performances of Black masculinities can be easily found on magazine covers, television shows, and popular websites. How do these representations affect the collective consciousness of Black men, while helping to construct a particular brand of masculinity that plays into the White imagination? This theoretical article explores how representations of Black masculinity vary in underground versus mainstream hip-hop, stemming directly from White patriarchal ideals of manhood. Conceptual and theoretical analyses of songs from the likes of Jay-Z and Dead Prez and Imani Perry’s Prophets of the Hood help provide an understanding of the parallels between hip-hop performances/identities and Black masculinities. Keywords Black masculinity, hip-hop, patriarchy, manhood 1Columbia University, New York, NY, USA Corresponding Author: Crystal Belle, PhD Candidate, English Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from jbs.sagepub.com at Mina Rees Library/CUNY Graduate Center on January 7, 2015 288 Journal of Black Studies 45(4) Introduction to and Musings on Black Masculinity in Hip-Hop What began as a lyrical movement in the South Bronx is now an international phenomenon.