Department of Historical Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USHMM Finding

https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Kindertransport Association Oral History Project Interview with TOM BERMAN June 25, 1994 KEY: • [brackets] describe action in the interview • Italics indicates a word in a foreign language, spelled correctly • {italics in bracket} indicates a word in a foreign language that may be incorrect • {brackets} indicate indecipherable words [FILE: 94_AG_01_TomBerman_06_25_94] Interviewer: Okay. Today is June 25th, 1994. We’re in New York. This is Anita Gross interviewing, and if you could introduce yourself? Tom: Okay. My name is Tom Berman, and I live in Kibbutz Amiad in Israel. And I’m one of the Czech Kindertransport Kinder. Interviewer: Now, before we go into your story, you were about to tell me a story about a lady at {Chatham}, was it? Tom: No. I was going to tell you about the British Refugee Committee, which operated in Prague in 1938 and 1939. It was run by a woman called Doreen Warriner. And their main function was really helping political refugees who were swelling into Prague, first from Germany, then from Austria, and finally from the Sudetenland. I really don’t know about this committee, who founded it or sponsored it, but eventually the Kindertransport operation functioned under the aegis of this committee. So when Nicky went and set things up in December, January 1939, he had to have the blessings of this British Refugee Committee, and worked under that umbrella, although his operation was essentially independent. And the original committee work did not include children at all. So the British Refugee Committee, after Winton left, the man who was running the Czech Kindertransport operation was a man called Trevor Chadwick. -

1 Sir Nicholas Winton

SLEZSKÁ UNIVERZITA V OPAVĚ Filozoficko-přírodovědecká fakulta v Opavě BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Opava 2021 Monika Hilzensauer SLEZSKÁ UNIVERZITA V OPAVĚ Filozoficko-přírodovědecká fakulta Monika Hilzensauer Obor: Angličtina pro školskou praxi Media Reception of Nicholas Winton’s Legacy in Great Britain and the Czech Republic Bakalářská práce Opava 2021 Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Marie Crhová, Ph.D., MA Abstract This bachelor thesis deals with the media image of Nicholas Winton’s rescue operation in which he managed to save hundreds of Czechoslovak children. Predominantly from Jewish families. The introductory part describes the life of Nicholas Winton and events before the outbreak of World War II. The thesis concentrates on the how the story was represented in the media and reflects responses not only in Great Britain but also in the Czech Republic. The Slovak director Matěj Mináč, with whom an interview was conducted especially for this thesis, is a noteworthy source of information. The thesis monitors documentary and features films in Czech and British cinematography trying to find out which of those countries could have a bigger influence on “Nicolas Winton’s legacy’s presentation.“ Key words: Sir Nicholas Winton, media, rescue operation, Great Britain, Czech Republic Abstrakt Bakalářská práce pojednává o mediálním obrazu záchranné akce Nicholase Wintona, při které se podařilo zachránit stovky československých dětí, převážně z židovských rodin. Úvodní část popisuje život Nicholase Wintonova a události před vypuknutím druhé světové války. Dále se práce soustřeďuje, jakým způsobem byl příběh mediálně prezentován a reflektuje ohlasy nejen ve Velké Británii, ale také v České republice. Neobvyklým zdrojem informací je rozhovor, poskytnut výhradně pro tuto práci, se slovenským režisérem Matějem Mináčem. -

The Kindertransport: History and Memory

THE KINDERTRANSPORT: HISTORY AND MEMORY Jennifer A. Norton B.A., Australian National University, 1976 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO FALL 2010 © 2010 Jennifer A. Norton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE KINDERTRANSPORT: HISTORY AND MEMORY A Thesis by Jennifer A. Norton Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Katerina Lagos __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Mona Siegel ____________________________ Date iii Student: Jennifer A. Norton I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Dr. Aaron Cohen Date Department of History iv Abstract of THE KINDERTRANSPORT: HISTORY AND MEMORY by Jennifer A. Norton The Kindertransport, a British scheme to bring unaccompanied mostly Jewish refugee children threatened by Nazism to Great Britain, occupies a unique place in modern British history. In the months leading up to the Second World War, it brought over 10,000 children under the age of seventeen into the United Kingdom without their parents, to be fostered by British families and re-emigrated when they turned eighteen. Mostly forgotten in the post-war period, the Kindertransport was rediscovered in the late 1980s when a fiftieth anniversary reunion was organized. Celebrated as an unprecedented act of benevolent rescue by a generous British Parliament and people, the Kindertransport has been subjected to little academic scrutiny. The salvation construct assumes that the Kinder, who were mostly silent for fifty years, experienced little hardship and that their survival more than compensated for any trauma they suffered. -

Journal BAS ^ Association of Jewish Refugees the Rescue of Refugee Scholars

VOLUME 9 NO.2 FEBRUARY 2009 journal BAS ^ Association of Jewish Refugees The rescue of refugee scholars eventy-five years ago, in 1933, Robbins on the spot. The AAC, which was the Academic Assistance Council, essentially mn from within the academic known from 1936 as the Society for community in Britain, then came into being the Protection of Science and very quickly. SLeaming, was founded. The AAC/SPSL was In May 1933, a letter signed by a list of a remarkable body that played a unique part leading figures in British university and in the rescue of scholars and scientists, intellectual life was published in The Times, mostly Jewish, who had been dismissed by proposing the establishment of an organi the Nazis from their posts at German and sation to rescue the careers and lives of Austrian universities and whose livelihoods, displaced academics. The Council's initial and lives, were endangered. declaration was signed by over 40 of Brit After the passing of the Gesetz zur ain's most eminent men of scholarship, Wiederherstellung des Bemfsbeamtentums including John Maynard Keynes, Gilbert of 7 April 1933, aimed at removing racially Murray, the Presidents of the Royal Society and politically undesirable persons from and the British Academy, and 9 Chancel the civil service, something like a quarter Esther Simpson OBE lors or Vice-Chancellors of universities and of the academic staff at German sciences), an extraordinary record of 7 Masters or Directors of colleges. The universities and research institutes were academic achievement. celebrated scientist Lord Rutherford became dismissed, of whom some 2,000, or about The two principal initiators of the AAC the AAC's first president. -

You Can Download the PDF Version of Sir Nicholas Winton's Life Story Here

Sir Nicholas Winton was born in Hampstead, London in 1909. For nine months in 1939 he rescued 669 children from Czechoslovakia, bringing them to the UK, thereby sparing them from the horrors of the Holocaust. Sir Nicholas died in July 2015, aged 106. ‘Why are you making such a big deal out of it? I just helped a little; I was in the right place at the right time.’ Despite Sir Nicholas’s humble and inspiring statement, it was more than just being in the right place at the right time, as his life story will show. Sir Nicholas Winton was born in Hampstead in 1909 to Jewish parents. In December 1938, at the age of 29, Winton cancelled a planned skiing holiday after being urged by a friend, Martin Blake, to go to Prague to see the dire situation for himself. The area had become overwhelmed with refugees after Germany had annexed the Sudetenland, a mostly German-speaking area of Czechoslovakia. Winton travelled to Czechoslovakia where he was sent by Doreen Warriner to see several refugee camps. Blake and Warriner were both working with an organisation to help relocate the adults, and Winton quickly realised that something had to be done to rescue the children who were caught up in the situation. He simply could not stand by. On Kristallnacht (9 and 10 November 1938), the Nazis had initiated a campaign of hatred against the Jewish population in all Nazi territories. An estimated 91 Jews were killed, 30,000 were arrested, and 267 synagogues were destroyed. Following this, the British government relaxed its immigration laws and agreed to allow in a limited number of children from Germany and Austria. -

Beware of Greeks Bearing Gifts

VOLUMEAJR JOURNAL 12 NO.1 JAjanuarNUARYY 2012 Beware of Greeks bearing gifts imeo Danaos et dona ferentes’ to that country by the Eurozone states number of political issues, are very much ‘ (‘I fear Greeks even when bear- provided an object lesson in the un- more difficult to manipulate and are Ting gifts’), warns the Trojan priest democratic potential of referenda, in the longer term a far more reliable Laocoön in Virgil’s Aeneid, in a vain unless employed in a manner properly reflection of the democratic process. attempt to deter the citizens of Troy defined by a democratic constitution. The first political leader in modern from accepting the wooden horse Greece had not had a referendum for times to rely on referenda was Emperor that the besieging Greek forces have 37 years, and then only in the wholly Napoleon III, whose French Second seemingly left as a gift, but which is exceptional circumstances of the coun- Empire (1852-70), in effect a form of in reality intended to bring about the try’s return to democracy after the plebiscitary dictatorship, was ‘constitu- destruction of the city. The ancient collapse of the military regime of the tionally’ founded on referenda. Having Greeks bequeathed the concept of ‘Greek colonels’ in 1974; the people been elected president of the Second democracy to the world, but their mod- were called on to vote on the future of Republic in 1848, Louis-Napoleon ern counterparts have recently helped Bonaparte carried out a coup d’état in to give currency to a more questionable December 1851 and seized dictatorial popular (not to say populist) device, the powers. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details A Moral Business: British Quaker work with Refugees from Fascism, 1933-39 Rose Holmes Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex December 2013 i I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ii University of Sussex Rose Holmes PhD Thesis A Moral Business: British Quaker work with Refugees from Fascism, 1933-39 Summary This thesis details the previously under-acknowledged work of British Quakers with refugees from fascism in the period leading up to the Second World War. This work can be characterised as distinctly Quaker in origin, complex in organisation and grassroots in implementation. The first chapter establishes how interwar British Quakers were able to mobilise existing networks and values of humanitarian intervention to respond rapidly to the European humanitarian crisis presented by fascism. The Spanish Civil War saw the lines between legal social work and illegal resistance become blurred, forcing British Quaker workers to question their own and their country’s official neutrality in the face of fascism. -

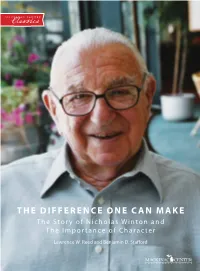

The Difference One Can Make the Story of Nicholas Winton and the Importance of Character

The Story of Nicholas Winton and The Importance of Character M A C k I N A C C E N T E R Classics THE DIFFERENCE ONE CAN MAKE The Story of Nicholas Winton and The Importance of Character Lawrence W. Reed and Benjamin D. Stafford Mackinac Center for Public Policy • 1 THE DIFFERENCE ONE CAN MAKE The Story of Nicholas Winton The Story of Nicholas Winton and The Importance of Character THE DIFFERENCE ONE CAN MAKE The Story of Nicholas Winton The truest hero does not think of himself as one, never advertises himself as such and does not perform the acts that make him a hero for either fame or fortune. He does not wait for government to act if he senses an opportunity to fix a problem himself. On July 27, 2006, in the quiet countryside of Maidenhead, England, we spent several hours with a true hero: Sir Nicholas Winton. His friends call him “Nicky.” n the fall of 1938, many Europeans were lulled appalling conditions in the midst of winter. into complacency by British Prime Minister Winton had planned a year-end ski trip to Swit- NIeville Chamberlain, who thought he had paci- zerland with a friend, but was later convinced by fied Adolf Hitler by handing him a large chunk of him at the last moment to come to Prague instead Czechoslovakia at Munich in late September. Win- because he had “something urgent to show him” — ston Churchill, who would succeed Chamberlain namely, the refugee problem. Near Prague, Winton in 1940, was among the wise and prescient who visited the freezing camps. -

The Pianist of Willesden Lane Based on the Book the Children of Willesden Lane by Mona Golabek & Lee Cohen Aaron Posner

The Guide A Theatergoer’s Resource The Pianist of Willesden Lane Based on the book The Children of Willesden Lane by Mona Golabek & Lee Cohen Aaron Posner Education & Community Programs Staff Kelsey Tyler Education & Community Programs Director Clara-Liis Hillier Education & Community Programs Associate Eric Werner Education & Community Programs Assistant Matthew B. Zrebski Resident Teaching Artist Resource Guide Contributors Benjamin Fainstein Literary Manager Mary Blair Production Dramaturg & Literary Associate Claudie Jean Fisher Table of Contents Public Relations and Publications Manager Mona Golabek . 2 Mikey Mann Hold On To Your Music Foundation . 3 Graphic Designer Characters in The Pianist of Willesden Lane . 4 German Expansion and Antisemitism . 4 PCS’s 2015–16 Education & Community Programs are generously supported by: Historical & Literary Timeline . 5 Kristallnacht: A Turning Point. 5 Defi ning the Word Refugee . 6 Who is Ruth Hect? . 7 A Rescuer’s Account . 8 Historical Sidelights: The Music of Terezin . 8 About the Oregon Holocaust Memorial . 9-10 PCS’s education programs are supported in part by a grant from the Oregon Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts. with additional support from Craig & Y. Lynne Johnston Holzman Foundation Mentor Graphics Foundation Autzen Foundation 1 and other generous donors. Mona Golabek Ms. Golabek is the founder and president of the non-profit organization Hold On To Your Music. She is an author, recording artist, radio host and internationally acclaimed concert pianist. Ms. Golabek was taught by her mother, Lisa Jura, who, along with Lisa’s mother Malka, is the subject of Ms. Golabek’s book, The Children Of Willesden Lane. -

DECEMBER 2020 JOURNAL the Association of Jewish Refugees

VOLUME 20 NO.12 DECEMBER 2020 JOURNAL The Association of Jewish Refugees LOOKING BACK The Year Our lead article looks back twelve months. But we are also inviting you to look back over 75 years of the AJR Journal and be part of our commemorative issue next in Review month – see page 3. The history books may well look back at 2020 as the start of Other highlights this month include a preview of two new memorials which are a pandemic. But as we reflect on the past twelve months it is being developed to honour two British important to realise there have been many other highlights, some icons of the Kindertransport (pages 10 & 11) and a light hearted look at the origin exciting, some sad. of Jewish names (page 9). Nostalgia is also at the root of our article on continental cooking (page 12) while the husband of one member was so inspired by a book review in our October issue that he has now written about his own father’s history. We hope you enjoy this final issue of 2020. News ............................................................ 3 Kristallnacht commemorated ........................ 4 Letter from Israel .......................................... 5 Letters to the Editor ................................ 6 – 7 2020 saw some excellent new TV dramas related to the Holocaust and Jewish refugees Art Notes...................................................... 8 The Name Game .......................................... 9 Icons of the Kindertransport ............... 10 – 11 Continental Cooking .................................. 12 First, there are those distinguished Jewish home in Vienna, one of three children of Put off travelling for life ............................. 13 refugees we have lost this year. The literary Béla and Lotte Horovitz. He was soaked Looking for................................................ -

Jewish Flight from the Bohemian Lands, 1938-1941

NETWORKS OF ESCAPE: JEWISH FLIGHT FROM THE BOHEMIAN LANDS, 1938-1941 Laura E. Brade A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Christopher R. Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch Donald Raleigh Susan Pennybacker Karen Auerbach © 2017 Laura E. Brade ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Laura E. Brade: Networks of Escape: Jewish Flight from the Bohemian Lands, 1938- 1941 (Under the direction of Christopher R. Browning and Chad Bryant) This dissertation tells the remarkable of a quarter of the Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia who managed to escape Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia between October 1938 and October 1941. Given all of the obstacles to emigration—an occupation government, a world war, international reluctance to grant visas, and extortionist Nazi emigration policies—this amounted to an extraordinary achievement. Czechoslovak Jews scattered across the globe, from Shanghai and India, to Madagascar and Ecuador. How did they accomplish this daunting task? The current scholarship has approached this question from the perspectives of governments, voluntary organizations, and individual refugees. However, by addressing the various actors in isolation, much of this research has focused either on condemning or heroizing these actors. As a result, the question of how Jewish refugees fled Europe has gone unanswered. Using the Bohemian Lands as a case study, I ask when and how rescue became possible. I make three major claims. First, I argue that a grassroots transnational network of escape facilitated leaving Nazi-occupied Europe. -

Nicholas Winton, Man and Myth: a Czech Perspective

Nicholas Winton, Man and Myth: A Czech Perspective Jana Burešová Nicholas Winton, whose Kindertransports from Czechoslovakia to Britain in 1939 saved 669 predominantly Jewish children at risk, has become a myth in his own time. To his ‘children’, however, who had longed to know his identity, Winton the man has become a respected paternal figure, for whom no honour would be sufficient. Diverse celebrations and projects commemorating the Kindertransports bear witness to their enduring esteem, and that of others around the world, but it is the Czech perspective that is central to this paper, linking past and present. Whilst acknowledging that Nicholas Winton did not work in isolation, from a contemporary Czech perspective it was the young British bachelor stockbroker who became the key rescuer of 669 predom- inantly Jewish children at risk in rump Czechoslovakia in 1939,1 following the ceding of the Sudetenland to Germany under the Munich Agreement of 29 September 1938. A few children were sent to London by aeroplane when Trevor Chadwick and Doreen Warriner worked in Prague with the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia (BCRC),2 but the majority departed without their parents in eight transports directly from Prague’s Wilson Station (thus were not part of the wider Kindertransport movement operating from Germany and Austria). The first group of children left on 14 March 1939, just hours before Germany seized what remained of Czechoslovakia. It subsequently became increasingly difficult for Jewish or politically active anti-Fascists such as Communists and Social Democrats, to escape with their families, but subject to various formalities, the Gestapo still allowed children to leave Czechoslo- vakia.